Universal "Horror": She seems to have an invisible touch

The notional context for this review of The Invisible Woman, Universal Pictures' release for Christmas week in 1940, is "let's look at all the far reaches of Universal horror!", and yet there's no movie that ever felt like it might be part of a horror franchise that so obviously isn't. The Invisible Woman is so far from horror that it makes The Curse of the Cat People look like splatterpunk in comparison. But here we are, nonetheless.

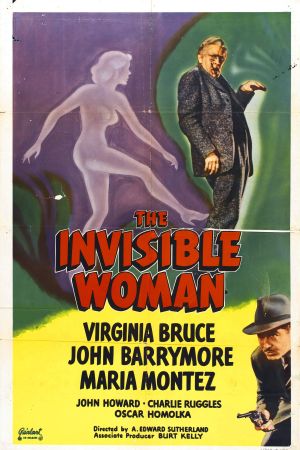

So if not horror, what is it? Why, a screwball romantic comedy, of course - it's about a woman, it has to be silly, obviously. Women aren't serious. Duh. All snark aside, The Invisible Woman is actually a pretty decent screwball at that - and all snark aside, it's got a streak of proto-feminism in it that you wouldn't necessarily expect from a wacky '40s comedy. Like any good screwball, the film starts off with the idle rich: petulant wealthy playboy Richard Russell (John Howard), willfully ignoring his put-upon advisers to keep pumping money in the direction of his father's old friend, Professor Gibbs (John Barrymore). Gibbs is a lovably dotty old soul, fixedly working on a machine to turn people invisible - he has perfected the technology, but it only lasts for an hour, which means that he has to perfectly time things to demonstrate his breakthrough to Richard. To that end, he scrounges up a guinea pig, K. Carroll - that would be Kitty Carroll (Virginia Bruce), a clothing model at a department store who is the most outspoken of three very beaten-down women working for the simply horrible Mr. Growley (Charles Lane). Her unexpected gender throws Gibbs, who's mostly concerned about the propriety of having a young lady disrobe for his tests, which causes him to call upon the unwilling help of his much put-upon housekeeper, Mrs. Jackson (Margaret Hamilton).

The test works, but Kitty's goal has never been to sit around patient and nude to prove a point for some absent-minded professor: she immediately throws herself into the task of sneaking off and tormenting Growley a bit, and scaring the old bastard into treating his employees better. Which means that she's gone when Richard comes to see Gibbs's wonderful breakthrough. She gets back just in time to instead cross paths with some gangsters in the service of Blackie Cole (Oskar Homolka), currently stranded in Mexico. And they are very much interested in Gibbs's work - what better way to spirit a notorious wanted man back across the border than by turning him invisible? And this triggers a chain of events that involves Kitty figuring out how to manipulate her invisibility to hoodwink the gangsters, while also impressing Richard as both a science project and a beautiful woman who, as the film always insists with a wink that we must remember, has to be naked to pull off her various unseen trickery.

The Invisible Woman has the misfortune to generally get worse at it goes along: by the time it turns into full-on slapstick with the gangsters (one of them played by slapstick expert Shemp Howard, a second-tier Three Stooges player), it has exhausted most of its comic ingenuity. For a while, though, it's honestly pretty terrific. And why not - no matter what it might seem from the insubstantial air of the whole thing, and the sense of piss-taking that cannot possibly avoid clinging to a movie that's so clearly meant to evoke The Invisible Man and The Invisible Man Returns in the most insincere way possible (it even shares story writers Joe May & Curt Siodmak with the latter film, which I assume has to be some kind of vestige of a much earlier concept), The Invisible Woman was a major deal, not a tossed-off bit of trash. This was, in fact, Universal's biggest-budget release of the year it came out. That money is absolutely well-spent, too: the disappearing effects are as much an improvement on the excellent The Invisible Man Returns as that movie was over the justly legendary The Invisible Man. By this point in the effects team's continued evolution, the only way to spot the seams is to know how they did it, and declare "I know that's where the seam has to be, ergo that is where the seam is". But damn me if the effect isn't perfect, or practically so. There's a moment of Kitty removing a dress in Growley's office that I truly don't think could be more convincing or flawlessly worked into the visual rhythm of the scene if it had been made by the finest computer technicians of modern Hollywood.

It's not only as an effects reel that the film succeeds, either - God knows, history is littered with the corpses of effects driven comedies that succeed on the technical level but puke out as entertainment, but The Invisible Woman mostly avoids that trap. It is not, on its own right, one of the great achievements in late screwball comedy. Universal was not ever a home for that genre, and while the screenwriters (Robert Lees, Fred Rinaldo, & Gertrude Purcell) and director A. Edward Sutherland all have some level of experience in the genre, their various careers are mostly devoid of what you might call timeless comedy masterworks. The film is dotted with smart lines, especially in the first third, and playful little twists that aren't terribly predictable, and some neat callbacks in the before-and-after scenes with the stricken Growley. There even a bit of possibly intentional meta-humor: in a film that incongruously cribs from a newly-revived horror franchise (The Invisible Man Returns had opened earlier in 1940, seven years after The Invisible Man), Margaret "Wicked Witch of the West" Hamilton scoffs with annoyance "What is this, Halloween?" in the early going.

That all being said, the film's success as a comedy is largely dependent on Barrymore and Bruce (and to a much smaller degree Homolka, who sputters angrily to good effect); those two-thirds of the leading trio trade lines with dazzling fluidity and snap. Something neither of them can do with Howard, I might add. One does not expect too much from them: Bruce's career is largely devoid of titles anybody but the most rabid fan of 1930s B-comedies would know off, and Barrymore was in the terminal stage of his career by this point, with only two films left before his drawn-out death from a lifetime of alcohol abuse. And he looked it; the relatively fleet Barrymore who'd made Midnight just one year prior is only intermittently detectable beneath the amiable befuddlement and general slowness of his Gibbs. But the wit is there; the sparkling comic touch still flares up when the right line or scene partner comes his way. And Bruce, feeling a little bit like a knock-off Stanwyck in her confident "tough broad" carriage, is a terrific scene partner, and a solid anchor in her own right; as certainly the film's busiest character if not always its most dynamic (these are not complex characters in general), she's frequently the only thing carrying the film's frothy and sarcastic comic threads along, and her disembodied voice oozes self-delight and cunning.

The overall energy is a bit saggy for a screwball: the sheer mania of a really great version of the form, like the same year's His Girl Friday, is conspicuously absent. And that plays out in all the ways it must: more languid pacing than feels right, less razor-edged dialogue, and never the smallest sense of real stakes (the gangster subplot is thrust at the film without feeling like it's ever naturally a part of it). Still and all, The Invisible Woman is a winning little bit of fluff. It's obviously better not to expect it to draw from the corpus of Universal horror, a misapprehension that seems to happen to far too many people who encounter the film in these latter days (that Universal has silently packaged it with the rest of the Invisible Man films on multiple DVD releases only encourages that problem), and budget notwithstanding, it has the feel of a casual, slight little B-movie comedy, screwball to be investigated only after you've exhausted all of the masterpieces. But nobody involved needed to feel the least bit ashamed of the results, and for a romcom spun-off from a horror franchise, that's as good as we can fairly expect.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

So if not horror, what is it? Why, a screwball romantic comedy, of course - it's about a woman, it has to be silly, obviously. Women aren't serious. Duh. All snark aside, The Invisible Woman is actually a pretty decent screwball at that - and all snark aside, it's got a streak of proto-feminism in it that you wouldn't necessarily expect from a wacky '40s comedy. Like any good screwball, the film starts off with the idle rich: petulant wealthy playboy Richard Russell (John Howard), willfully ignoring his put-upon advisers to keep pumping money in the direction of his father's old friend, Professor Gibbs (John Barrymore). Gibbs is a lovably dotty old soul, fixedly working on a machine to turn people invisible - he has perfected the technology, but it only lasts for an hour, which means that he has to perfectly time things to demonstrate his breakthrough to Richard. To that end, he scrounges up a guinea pig, K. Carroll - that would be Kitty Carroll (Virginia Bruce), a clothing model at a department store who is the most outspoken of three very beaten-down women working for the simply horrible Mr. Growley (Charles Lane). Her unexpected gender throws Gibbs, who's mostly concerned about the propriety of having a young lady disrobe for his tests, which causes him to call upon the unwilling help of his much put-upon housekeeper, Mrs. Jackson (Margaret Hamilton).

The test works, but Kitty's goal has never been to sit around patient and nude to prove a point for some absent-minded professor: she immediately throws herself into the task of sneaking off and tormenting Growley a bit, and scaring the old bastard into treating his employees better. Which means that she's gone when Richard comes to see Gibbs's wonderful breakthrough. She gets back just in time to instead cross paths with some gangsters in the service of Blackie Cole (Oskar Homolka), currently stranded in Mexico. And they are very much interested in Gibbs's work - what better way to spirit a notorious wanted man back across the border than by turning him invisible? And this triggers a chain of events that involves Kitty figuring out how to manipulate her invisibility to hoodwink the gangsters, while also impressing Richard as both a science project and a beautiful woman who, as the film always insists with a wink that we must remember, has to be naked to pull off her various unseen trickery.

The Invisible Woman has the misfortune to generally get worse at it goes along: by the time it turns into full-on slapstick with the gangsters (one of them played by slapstick expert Shemp Howard, a second-tier Three Stooges player), it has exhausted most of its comic ingenuity. For a while, though, it's honestly pretty terrific. And why not - no matter what it might seem from the insubstantial air of the whole thing, and the sense of piss-taking that cannot possibly avoid clinging to a movie that's so clearly meant to evoke The Invisible Man and The Invisible Man Returns in the most insincere way possible (it even shares story writers Joe May & Curt Siodmak with the latter film, which I assume has to be some kind of vestige of a much earlier concept), The Invisible Woman was a major deal, not a tossed-off bit of trash. This was, in fact, Universal's biggest-budget release of the year it came out. That money is absolutely well-spent, too: the disappearing effects are as much an improvement on the excellent The Invisible Man Returns as that movie was over the justly legendary The Invisible Man. By this point in the effects team's continued evolution, the only way to spot the seams is to know how they did it, and declare "I know that's where the seam has to be, ergo that is where the seam is". But damn me if the effect isn't perfect, or practically so. There's a moment of Kitty removing a dress in Growley's office that I truly don't think could be more convincing or flawlessly worked into the visual rhythm of the scene if it had been made by the finest computer technicians of modern Hollywood.

It's not only as an effects reel that the film succeeds, either - God knows, history is littered with the corpses of effects driven comedies that succeed on the technical level but puke out as entertainment, but The Invisible Woman mostly avoids that trap. It is not, on its own right, one of the great achievements in late screwball comedy. Universal was not ever a home for that genre, and while the screenwriters (Robert Lees, Fred Rinaldo, & Gertrude Purcell) and director A. Edward Sutherland all have some level of experience in the genre, their various careers are mostly devoid of what you might call timeless comedy masterworks. The film is dotted with smart lines, especially in the first third, and playful little twists that aren't terribly predictable, and some neat callbacks in the before-and-after scenes with the stricken Growley. There even a bit of possibly intentional meta-humor: in a film that incongruously cribs from a newly-revived horror franchise (The Invisible Man Returns had opened earlier in 1940, seven years after The Invisible Man), Margaret "Wicked Witch of the West" Hamilton scoffs with annoyance "What is this, Halloween?" in the early going.

That all being said, the film's success as a comedy is largely dependent on Barrymore and Bruce (and to a much smaller degree Homolka, who sputters angrily to good effect); those two-thirds of the leading trio trade lines with dazzling fluidity and snap. Something neither of them can do with Howard, I might add. One does not expect too much from them: Bruce's career is largely devoid of titles anybody but the most rabid fan of 1930s B-comedies would know off, and Barrymore was in the terminal stage of his career by this point, with only two films left before his drawn-out death from a lifetime of alcohol abuse. And he looked it; the relatively fleet Barrymore who'd made Midnight just one year prior is only intermittently detectable beneath the amiable befuddlement and general slowness of his Gibbs. But the wit is there; the sparkling comic touch still flares up when the right line or scene partner comes his way. And Bruce, feeling a little bit like a knock-off Stanwyck in her confident "tough broad" carriage, is a terrific scene partner, and a solid anchor in her own right; as certainly the film's busiest character if not always its most dynamic (these are not complex characters in general), she's frequently the only thing carrying the film's frothy and sarcastic comic threads along, and her disembodied voice oozes self-delight and cunning.

The overall energy is a bit saggy for a screwball: the sheer mania of a really great version of the form, like the same year's His Girl Friday, is conspicuously absent. And that plays out in all the ways it must: more languid pacing than feels right, less razor-edged dialogue, and never the smallest sense of real stakes (the gangster subplot is thrust at the film without feeling like it's ever naturally a part of it). Still and all, The Invisible Woman is a winning little bit of fluff. It's obviously better not to expect it to draw from the corpus of Universal horror, a misapprehension that seems to happen to far too many people who encounter the film in these latter days (that Universal has silently packaged it with the rest of the Invisible Man films on multiple DVD releases only encourages that problem), and budget notwithstanding, it has the feel of a casual, slight little B-movie comedy, screwball to be investigated only after you've exhausted all of the masterpieces. But nobody involved needed to feel the least bit ashamed of the results, and for a romcom spun-off from a horror franchise, that's as good as we can fairly expect.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

Categories: comedies, gangster pictures, romcoms, science fiction, universal horror