To become immortal and then die

A review requested by Ryan J, with thanks for contributing to the ACS Fundraiser.

Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 debut feature and declaration of war Breathless* is a curious case. In hindsight, everything that is most daring about it would be repeated to stronger effect in more interesting movies overall by the same director - most directly in Band of Outsiders and Pierrot le fou, though almost everything he made throughout the 1960s reworks some element of his debut - which makes it frankly a wee bit harder to regard it with the same esteem that besotted critics and cinephiles did when it was brand new.And yet, this is The One. The single movie that you need to see and grapple with if you're going to have a reckoning with Godard's first phase, and arguably with the entirety of French cinema in that decade (arguably with any of the European New Waves of the 1960s and 1970s, of which the French New Wave that Breathless co-created with François Truffaut's The 400 Blows was the wellspring). It's indisputably on the shortlist (the top ten, let's say) of Movies You Need To See if you're going to have a proper conception of cinema history and the potential of cinematic form. So even while my heart says that we should care more about Band of Outsiders or Contempt or Masculin féminin, my head says not to be fucking daft.

The place: Paris in the '60s. The time: America during Prohibition. Here we meet self-identified bastard Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a young man who has certainly built most of his personality from a steady diet of B-grade Hollywood crime pictures, not unlike the writer-director who created him. He's apparently some kind of a real criminal, though you could be forgiven for supposing it's all an overbaked fantasy in his noir-soaked head, and he's also a loudmouth given to braggadocio and toxic sexism. Who's to say if we're supposed to admire him or find him absurdly hateful: the camera insinuates us right along side him, Belmondo's prickly acting and the relentlessly, self-consciously disagreeable things he keeps saying repel us, and the editing by Cécile Decugis, famously, doesn't much intend that we regard him as a real character at all: he's a dude in a movie with the misfortune to somewhat suspect that's the case, which leads him to act far too much like a movie character. And this is partially to blame for why he shoots a cop during a drive in the country.

I hope it says more about the film than my inattentiveness when I declare that, having seen Breathless God knows how many times now (I went to film school, and I'm a self-professed Godard fan - that's good for at least six viewings right there), and remembering with great fondness that it's the first of Godard's gangster movie riffs, I am infallibly surprised to remember that the entire plot hinges on Michel's murder of a cop. It's just not that kind of movie, except that of course it very much is - the rest of the film down to the last scene all revolves around the detectives hunting Michel down and ultimately getting their hooks into visiting American student Patricia (Jean Seberg), possibly the most important of his current paramours; she's the co-lead of the film, but at the same time they don't really seem to like each other very much, the evidence of the signature bedroom scene notwithstanding. But I'm going all out of order.

It is so deeply tempting and dangerously easy to lock in and adore Breathless for all its little flair: the popular introduction of the soon-to-be-ubiquitous technique of the jump cut, which I think we typically remember as showing up during a car ride that gets propelled ahead in an attempt to make it seem artificially exciting and tense, with the full aid and comfort of Martial Solal's pounding jazz-influenced score. But that's at least the third major scene involving jump cutting, and the other two are both conversations, one between Michel and another one of his girlfriends (it just so happens to be right after Michel mentions his recent work at famed movie studio Cinécitta), one between Patricia and the editor nudging her journalism career forward, both relatively banal. I wouldn't suggest anything so trite as to say that the jump cutting is the film's attempt to hurry us through the dully quotidian scenes that shouldn't even be in a nervy gangster thriller in the first place, but I wouldn't tell you not to make that claim for them.

Or there's the brilliant way that the killing of the cop is shot, with close-ups of the gun and the unsynchronised sound of an gunshot, immediately followed by a scene moments later - the jarring image editing and discontinuous sound standing in as surrogates for the act of violence instead of that act being depicted (both times a human being is murdered with a gun in Breathless, the sound of the gunshot does not match the onscreen imagery. Just a fun thing to be aware of). Which would easily lead us to the film's bravura use of sound editing, which for my money is the far bolder aspect of Breathless's aesthetic developments, though the film editing was more quickly, more widely copied. And then I would talk about the floating, ghostly voices in the scene with a great, famous author (played by New Wave progenitor Jean-Pierre Melville) being peppered with high-minded but insipid philosophical questions leading to purposefully shitty answers ("Rilke was a great poet, so undoubtedly right" is his considered response to some journalist's "look how I did my research!" moment), and maybe the way that the score keeps jolting its way into the movie, mostly but not always motivated by the onscreen action.

The mistake I have personally had in the past with doing that is to lose the forest for the trees: Breathless is not just the sum of Godard's aesthetic. And it is here, I think, that something on the order of Masculin féminin argues for itself as an improvement over Godard's debut, since that film more clearly demonstrates the reason for its aesthetic rather than simply wandering, as Breathless occasionally does, into "look at me, I can be formally outrageous for the sake of it!" territory.

So let's not indulge that limited reading, huh? Step back from the jump cutting and the sound, from Seberg's stiff French and Belmondo's posing for the camera, from the litany of Hollywood genre film references and in-jokes, and Breathless does in fact take on quite a distinctive shape. It's not just Godard's riff on gangster movies of both the American and French tradition, and not even just his riff on the kind of young people so infatuated with pop culture that they'd fall into the trap of defining their identity in terms of the movies they enjoy most. Though that's getting us closer.

It's really nothing else but the first in a chain of films where Godard is interested in youth itself, the issue of how young, or at least young-ish individuals manage to find their way around a quickly globalising world whose values are evolving at a startling rate. For Michel, this means retrenching to an archly conservative, performance-based notion of masculinity, and the whole movie bends itself around him - though by no means does it do so uncritically - and eschewing the real world in favor of the fantastic one he thinks of in movies.

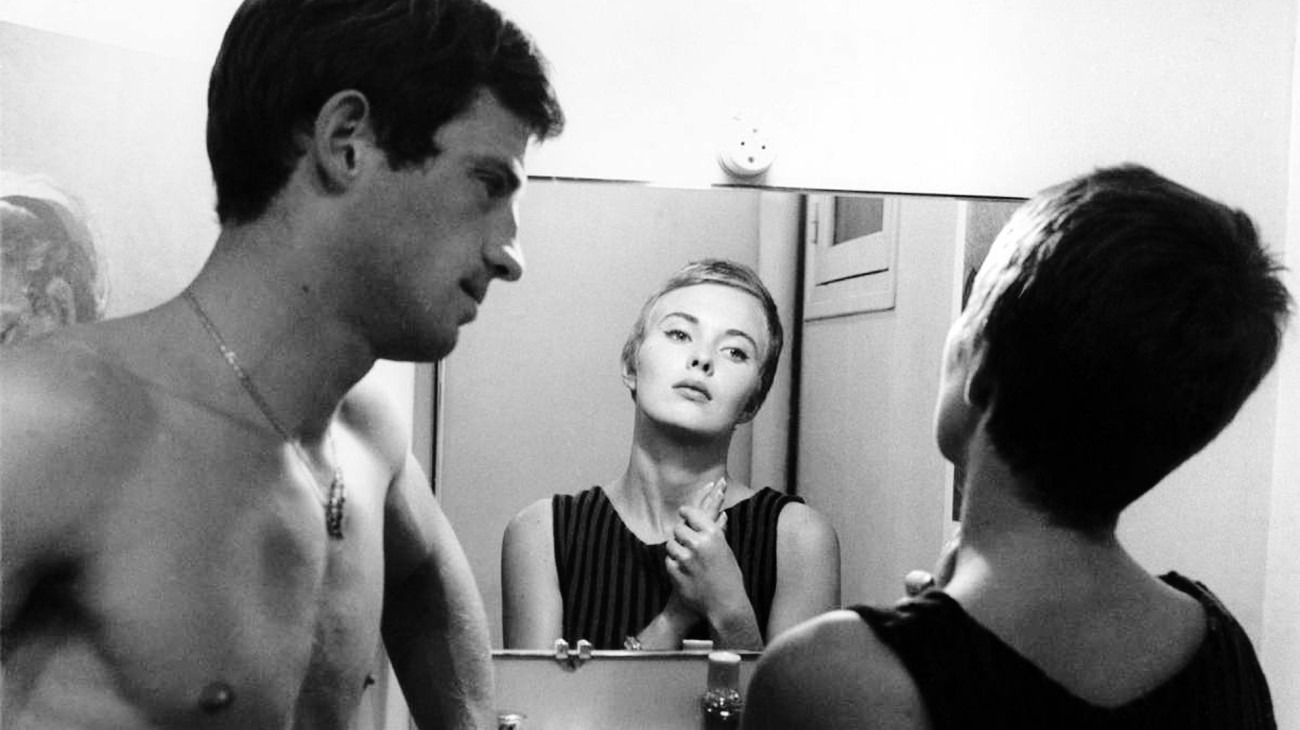

Reality, in the form of aesthetic realism, insists on pushing its way through; I return us to that bedroom scene, in which a film constructed out of three- and four-minute blasts of narrative propulsion jams on the brakes for 23 minutes as Michel surprises Patricia in her hotel, they have sex, they discuss art insofar as his dickish, petulant refusal to take her questions seriously permits. The editing slows down, the lighting (from cinematographer Raoul Coutard) turns ragged and rough, the setting becomes almost sublimely unexceptional and devoid of storytelling momentum. It's like the "other" New Wave, the one by Truffaut (who co-wrote this film) and Rohmer, based in languid humanistic moments of unadorned conversation pushes its way into Godard's more manic, formalist New Wave for the duration of a whole act. But for the most part, the film permits Michel his fantasy, even though it requires him to be betrayed by a woman who seems a little perplexed herself why she's been obliged to be a femme fatale in the film's glorious final shot, a deeply ambivalent close-up on Seberg's face that ends with her turning her back on us.

The jarring and groundbreaking post-modernism of the filmmaking - Breathless is not the first movie that is aware that it's a movie and which acts to make sure we're aware that it's a movie (that's not even an invention of the sound era), but it's the film that kickstarted that as a tradition that has never since gone fully into hibernation - isn't, then, simply a radical response to the hidebound aesthetics of the bulk of post-war French cinema. Of course it's partly that. To assert otherwise would be to deny the volumes of Godard's own writing at this time, when he was still a critic at the legendary Cahiers du cinéma. But the aesthetic violence of the film is also an attempt to encapsulate the rage of its characters, whose youthful energy is given no functional outlet, and so must explode somehow. Within the world of the film, that means destroying the traditional structures of cinema. In the real world, that meant the increasing unrest of the '60s that resulted in the May 1968 protests across Europe - and while I'll not be such a Godardian as to claim that he could predict those protests were coming, any quick glance at his films in '67 - Week End, La chinoise - and their continued development of the self-destruction begun with Breathless suggests that the nascent youthful resentment of this film had continued festering and growing ever bolder, more radical, and more intense. As much as they're any one thing, Godard's films are deliberate diagnoses of the era in which he made them, and Breathless is as precise an identification of the culture of the '60s-to-come as I have seen in the movies.

*A rare case of English winning the foreign title lottery - Breathless is snazzy and punchy and abrupt, all things it shares with the film, in a way that the original À bout de souffle isn't.

Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 debut feature and declaration of war Breathless* is a curious case. In hindsight, everything that is most daring about it would be repeated to stronger effect in more interesting movies overall by the same director - most directly in Band of Outsiders and Pierrot le fou, though almost everything he made throughout the 1960s reworks some element of his debut - which makes it frankly a wee bit harder to regard it with the same esteem that besotted critics and cinephiles did when it was brand new.And yet, this is The One. The single movie that you need to see and grapple with if you're going to have a reckoning with Godard's first phase, and arguably with the entirety of French cinema in that decade (arguably with any of the European New Waves of the 1960s and 1970s, of which the French New Wave that Breathless co-created with François Truffaut's The 400 Blows was the wellspring). It's indisputably on the shortlist (the top ten, let's say) of Movies You Need To See if you're going to have a proper conception of cinema history and the potential of cinematic form. So even while my heart says that we should care more about Band of Outsiders or Contempt or Masculin féminin, my head says not to be fucking daft.

The place: Paris in the '60s. The time: America during Prohibition. Here we meet self-identified bastard Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a young man who has certainly built most of his personality from a steady diet of B-grade Hollywood crime pictures, not unlike the writer-director who created him. He's apparently some kind of a real criminal, though you could be forgiven for supposing it's all an overbaked fantasy in his noir-soaked head, and he's also a loudmouth given to braggadocio and toxic sexism. Who's to say if we're supposed to admire him or find him absurdly hateful: the camera insinuates us right along side him, Belmondo's prickly acting and the relentlessly, self-consciously disagreeable things he keeps saying repel us, and the editing by Cécile Decugis, famously, doesn't much intend that we regard him as a real character at all: he's a dude in a movie with the misfortune to somewhat suspect that's the case, which leads him to act far too much like a movie character. And this is partially to blame for why he shoots a cop during a drive in the country.

I hope it says more about the film than my inattentiveness when I declare that, having seen Breathless God knows how many times now (I went to film school, and I'm a self-professed Godard fan - that's good for at least six viewings right there), and remembering with great fondness that it's the first of Godard's gangster movie riffs, I am infallibly surprised to remember that the entire plot hinges on Michel's murder of a cop. It's just not that kind of movie, except that of course it very much is - the rest of the film down to the last scene all revolves around the detectives hunting Michel down and ultimately getting their hooks into visiting American student Patricia (Jean Seberg), possibly the most important of his current paramours; she's the co-lead of the film, but at the same time they don't really seem to like each other very much, the evidence of the signature bedroom scene notwithstanding. But I'm going all out of order.

It is so deeply tempting and dangerously easy to lock in and adore Breathless for all its little flair: the popular introduction of the soon-to-be-ubiquitous technique of the jump cut, which I think we typically remember as showing up during a car ride that gets propelled ahead in an attempt to make it seem artificially exciting and tense, with the full aid and comfort of Martial Solal's pounding jazz-influenced score. But that's at least the third major scene involving jump cutting, and the other two are both conversations, one between Michel and another one of his girlfriends (it just so happens to be right after Michel mentions his recent work at famed movie studio Cinécitta), one between Patricia and the editor nudging her journalism career forward, both relatively banal. I wouldn't suggest anything so trite as to say that the jump cutting is the film's attempt to hurry us through the dully quotidian scenes that shouldn't even be in a nervy gangster thriller in the first place, but I wouldn't tell you not to make that claim for them.

Or there's the brilliant way that the killing of the cop is shot, with close-ups of the gun and the unsynchronised sound of an gunshot, immediately followed by a scene moments later - the jarring image editing and discontinuous sound standing in as surrogates for the act of violence instead of that act being depicted (both times a human being is murdered with a gun in Breathless, the sound of the gunshot does not match the onscreen imagery. Just a fun thing to be aware of). Which would easily lead us to the film's bravura use of sound editing, which for my money is the far bolder aspect of Breathless's aesthetic developments, though the film editing was more quickly, more widely copied. And then I would talk about the floating, ghostly voices in the scene with a great, famous author (played by New Wave progenitor Jean-Pierre Melville) being peppered with high-minded but insipid philosophical questions leading to purposefully shitty answers ("Rilke was a great poet, so undoubtedly right" is his considered response to some journalist's "look how I did my research!" moment), and maybe the way that the score keeps jolting its way into the movie, mostly but not always motivated by the onscreen action.

The mistake I have personally had in the past with doing that is to lose the forest for the trees: Breathless is not just the sum of Godard's aesthetic. And it is here, I think, that something on the order of Masculin féminin argues for itself as an improvement over Godard's debut, since that film more clearly demonstrates the reason for its aesthetic rather than simply wandering, as Breathless occasionally does, into "look at me, I can be formally outrageous for the sake of it!" territory.

So let's not indulge that limited reading, huh? Step back from the jump cutting and the sound, from Seberg's stiff French and Belmondo's posing for the camera, from the litany of Hollywood genre film references and in-jokes, and Breathless does in fact take on quite a distinctive shape. It's not just Godard's riff on gangster movies of both the American and French tradition, and not even just his riff on the kind of young people so infatuated with pop culture that they'd fall into the trap of defining their identity in terms of the movies they enjoy most. Though that's getting us closer.

It's really nothing else but the first in a chain of films where Godard is interested in youth itself, the issue of how young, or at least young-ish individuals manage to find their way around a quickly globalising world whose values are evolving at a startling rate. For Michel, this means retrenching to an archly conservative, performance-based notion of masculinity, and the whole movie bends itself around him - though by no means does it do so uncritically - and eschewing the real world in favor of the fantastic one he thinks of in movies.

Reality, in the form of aesthetic realism, insists on pushing its way through; I return us to that bedroom scene, in which a film constructed out of three- and four-minute blasts of narrative propulsion jams on the brakes for 23 minutes as Michel surprises Patricia in her hotel, they have sex, they discuss art insofar as his dickish, petulant refusal to take her questions seriously permits. The editing slows down, the lighting (from cinematographer Raoul Coutard) turns ragged and rough, the setting becomes almost sublimely unexceptional and devoid of storytelling momentum. It's like the "other" New Wave, the one by Truffaut (who co-wrote this film) and Rohmer, based in languid humanistic moments of unadorned conversation pushes its way into Godard's more manic, formalist New Wave for the duration of a whole act. But for the most part, the film permits Michel his fantasy, even though it requires him to be betrayed by a woman who seems a little perplexed herself why she's been obliged to be a femme fatale in the film's glorious final shot, a deeply ambivalent close-up on Seberg's face that ends with her turning her back on us.

The jarring and groundbreaking post-modernism of the filmmaking - Breathless is not the first movie that is aware that it's a movie and which acts to make sure we're aware that it's a movie (that's not even an invention of the sound era), but it's the film that kickstarted that as a tradition that has never since gone fully into hibernation - isn't, then, simply a radical response to the hidebound aesthetics of the bulk of post-war French cinema. Of course it's partly that. To assert otherwise would be to deny the volumes of Godard's own writing at this time, when he was still a critic at the legendary Cahiers du cinéma. But the aesthetic violence of the film is also an attempt to encapsulate the rage of its characters, whose youthful energy is given no functional outlet, and so must explode somehow. Within the world of the film, that means destroying the traditional structures of cinema. In the real world, that meant the increasing unrest of the '60s that resulted in the May 1968 protests across Europe - and while I'll not be such a Godardian as to claim that he could predict those protests were coming, any quick glance at his films in '67 - Week End, La chinoise - and their continued development of the self-destruction begun with Breathless suggests that the nascent youthful resentment of this film had continued festering and growing ever bolder, more radical, and more intense. As much as they're any one thing, Godard's films are deliberate diagnoses of the era in which he made them, and Breathless is as precise an identification of the culture of the '60s-to-come as I have seen in the movies.

*A rare case of English winning the foreign title lottery - Breathless is snazzy and punchy and abrupt, all things it shares with the film, in a way that the original À bout de souffle isn't.