Blockbuster History: Watching other people playing video games

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the notorious insta-flop Pixels is an adventure about a group of competition-level video game players. It's also pandering to '80s nostalgia, so let's go ahead and travel back to that decade

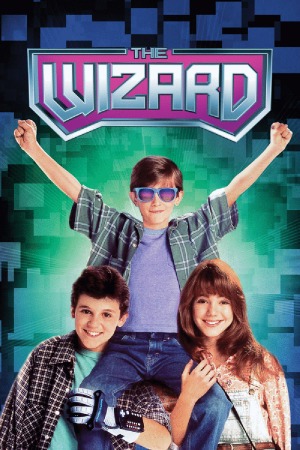

The dominant criticism of The Wizard when it was new in 1989 was that it was transparently a commercial for Nintendo, crudely fashioned into a simulacrum of a feature film, and the idea was this was somehow a filthy trick to play on the children in its target audience. Having been exactly the right age with exactly the right interests to care, I would like to promise those worried adults: we knew. The fact that it was a commercial was in fact exactly the draw - this was the movie which would offer North America its first opportunity to see footage from Super Mario Bros. 3, and it was advertised on precisely that basis. If you were Nintendo-playing grade schooler in '89, this was about on par with Christ returning to play Himself in a movie before inaugurating the end times. That being said, despite being the exact sort of person who this movie was made for, I never bothered seeing it - I mean, hell, it was a feature-length commercial.

A quarter of a century later,* The Wizard looks no less like a commercial, and its single-minded commitment to the style and attitude that children of the late 1980s perceived as cool leaves it feeling very much like a communication from some alien species. The last half-hour of the movie, in particular, is an incomprehensible frenzy of sound and noise and color that feel like a bad acid trip. Or perhaps a really, really good acid trip.

Not that you would know this at first, for among the film's many peculiarities is its earnest desire for almost its entire first hour to function as a mordant domestic drama. The opening image, underneath the credits, is a telephoto shot of nine-year-old Jimmy Woods (Luke Edwards) walking along a featureless desert road, arriving nowhere and doing it slowly. It's a dead ringer for something out of a '70s movie, and it's frankly rather presumptuous for an '80s kids film of any sort, let alone one that has every intention of trying to sell us video games. And this will very much continue on as the film sketches its rather bitter family scenario: Jimmy is the autistic son of the divorced Sam Woods (Beau Bridges) and Christine Bateman (Wendy Phillips), the latter of whom has since remarried a snappish control freak (Sam McMurray), and retained custody of Jimmy. Having finally concluded that he's too difficult for his and everyone else's own good, the Batemans have made the hard choice to put him in an institution. This makes Sam unhappy, but it really pisses off his second son, Corey (Fred Savage), from his first marriage, who decides to spring Jimmy from the institution and run away from home with him. The Batemans hire a sleazy bounty hunter, Putnam (Will Seltzer), to track the boys down, while Sam, anxious to keep Corey from their punitive hands (we are assured that Christine, in her days as Corey's stepmother, didn't even feign affection for the boy), takes his eldest son, Corey's full brother Nick (Christian Slater), on a trip with him to track the boys down.

So far, so good: a little over-plotted, and you need to pay a bit of attention to catch all of the nuances of how these people are related and what they think about each other, but if the world actually required a serious '70s style domestic drama about the ugly fallout from a divorce done up as an adventurous road movie for children - and I really do not suppose that it did - this is good enough to get the job done. But this is merely the overture; the warm-up, even. From here, thing start to get enormously weird, and they do it fast. Trying to buy a bus ticket, Corey and Jimmy encounter Haley (Jenny Lewis), a girl Corey's age who seems to be some kind of '30s Depression-comedy vagabond in the body of a 1989 13-year-old. It's astonishing. She throws out punny, cutting quips, delivered at a rapid-fire clip in a snarky tone that the young actor is visibly confused by herself; it's like director Todd Holland took her aside on the first day of shooting to demand that she play her character as Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve and refused thereafter to listen to any of her questions as to what the hell that meant.

As the quick-witted dame with a con artist's soul, it's Haley who figures out how to monetise Jimmy's newly discovered skill at video games, by betting against businessmen and tough skaterboarders and the like. It's at this point that it's impossible to stop noticing that The Wizard is no less than Rain Man with children, and thus at this point The Wizard turns into a mostly surreal experience. Not totally surreal; we still have to get to the final act for that. Before that happens, our plucky trio has to cross paths with Lucas (Jackey Vinson), the ballingest video game hot shot in the Southwest, who introduces them to the holiness that is the Nintendo Power Glove, and after quietly slipping around in the background, with a little music from Super Mario Bros. 2 here, or a little flash of the NES controller there, the movie explodes into its truest self, as a shameless plug for buying things from Nintendo, playing Nintendo, idealising Nintendo as the pinnacle achievement of human technology and society. For the Power Glove. One of the most notoriously awful video game peripherals ever built. "I love the Power Glove. It's so bad" the boy says with the self-satisfaction of a dreadful yuppie from the era's sex comedies, and it at least half of that is the truest statement in this entire movie.

The shameless wallowing in Nintendo prowess and ownership as the keenest of all social dominance markers, plus Holland and screenwriter David Chisholm's constant inability to treat this kids' movie like a kids movie, forcing the poor child actors into positions of pantomiming adult behavior in their conversations about video games, or sometimes accusing innocent bystanders of being pedophiles ("He! Touched! My! Breast!"), plus the dazzlingly dated costumes and hairstyles, are all enough to make this an extravagantly weird viewing experience, now that we're a generation past its sell-by date. But we're still not to the part where the movie goes off a cliff. That happens at Universal Studios Hollywood, where Video Armageddon, the nation's premier Nintendo gaming competition, is held. For starters, the set of Video Armageddon looks like a combination of the boiler room on an aircraft carrier and an athletic shoe store. Second, the event's announcer (Steven Grives) declaims lines in a manner not compatible with any dialect of English, dancing about and grinning manically like he is the actual Satan and this is some particularly tacky corner of Hell. Third, there's not even a cursory relationship between the proclamations of gameplay and points scored announced over the loudspeaker, and what we can actually see with our own damn eyes.

In short, what is most mystifying about The Wizard isn't that it's a movie set up as a feature-length ad for video games despite being welded onto an emotionally lacerating domestic drama: it's that it's an ad for video games that makes video games look like a peyote hallucination, throwing fragments of game imagery up on screen in ways that make the games themselves seem like jagged, incomprehensible masses of arbitrary movement and the players all puppets in the grip of some helpless madness. It makes videogaming look like the most unpleasant, frenzied activity on Earth, better suited to punishment than entertainment

It's shockingly bad, and coupled with the enormous tonal shifts that happen throughout the movie, it feels basically like The Wizard has an aneurysm right as we're watching it. This is an appallingly jagged and messy film, ugly to look at and saddled with narrative developments that simply happen because the film knows that its end point has to be a video game competition. Everything within it is incongruous to everything else. For those who grew up in the video game culture it depicts, I think it probably serves as a fascinating enough snapshot to serve as a kind of hell-dimension nostalgia trip; but for everyone, its completely batshit insane concept of what human beings are like and what kind of physical spaces the inhabit makes it a thoroughly mesmerising So Bad It's Good spectacular.

The dominant criticism of The Wizard when it was new in 1989 was that it was transparently a commercial for Nintendo, crudely fashioned into a simulacrum of a feature film, and the idea was this was somehow a filthy trick to play on the children in its target audience. Having been exactly the right age with exactly the right interests to care, I would like to promise those worried adults: we knew. The fact that it was a commercial was in fact exactly the draw - this was the movie which would offer North America its first opportunity to see footage from Super Mario Bros. 3, and it was advertised on precisely that basis. If you were Nintendo-playing grade schooler in '89, this was about on par with Christ returning to play Himself in a movie before inaugurating the end times. That being said, despite being the exact sort of person who this movie was made for, I never bothered seeing it - I mean, hell, it was a feature-length commercial.

A quarter of a century later,* The Wizard looks no less like a commercial, and its single-minded commitment to the style and attitude that children of the late 1980s perceived as cool leaves it feeling very much like a communication from some alien species. The last half-hour of the movie, in particular, is an incomprehensible frenzy of sound and noise and color that feel like a bad acid trip. Or perhaps a really, really good acid trip.

Not that you would know this at first, for among the film's many peculiarities is its earnest desire for almost its entire first hour to function as a mordant domestic drama. The opening image, underneath the credits, is a telephoto shot of nine-year-old Jimmy Woods (Luke Edwards) walking along a featureless desert road, arriving nowhere and doing it slowly. It's a dead ringer for something out of a '70s movie, and it's frankly rather presumptuous for an '80s kids film of any sort, let alone one that has every intention of trying to sell us video games. And this will very much continue on as the film sketches its rather bitter family scenario: Jimmy is the autistic son of the divorced Sam Woods (Beau Bridges) and Christine Bateman (Wendy Phillips), the latter of whom has since remarried a snappish control freak (Sam McMurray), and retained custody of Jimmy. Having finally concluded that he's too difficult for his and everyone else's own good, the Batemans have made the hard choice to put him in an institution. This makes Sam unhappy, but it really pisses off his second son, Corey (Fred Savage), from his first marriage, who decides to spring Jimmy from the institution and run away from home with him. The Batemans hire a sleazy bounty hunter, Putnam (Will Seltzer), to track the boys down, while Sam, anxious to keep Corey from their punitive hands (we are assured that Christine, in her days as Corey's stepmother, didn't even feign affection for the boy), takes his eldest son, Corey's full brother Nick (Christian Slater), on a trip with him to track the boys down.

So far, so good: a little over-plotted, and you need to pay a bit of attention to catch all of the nuances of how these people are related and what they think about each other, but if the world actually required a serious '70s style domestic drama about the ugly fallout from a divorce done up as an adventurous road movie for children - and I really do not suppose that it did - this is good enough to get the job done. But this is merely the overture; the warm-up, even. From here, thing start to get enormously weird, and they do it fast. Trying to buy a bus ticket, Corey and Jimmy encounter Haley (Jenny Lewis), a girl Corey's age who seems to be some kind of '30s Depression-comedy vagabond in the body of a 1989 13-year-old. It's astonishing. She throws out punny, cutting quips, delivered at a rapid-fire clip in a snarky tone that the young actor is visibly confused by herself; it's like director Todd Holland took her aside on the first day of shooting to demand that she play her character as Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve and refused thereafter to listen to any of her questions as to what the hell that meant.

As the quick-witted dame with a con artist's soul, it's Haley who figures out how to monetise Jimmy's newly discovered skill at video games, by betting against businessmen and tough skaterboarders and the like. It's at this point that it's impossible to stop noticing that The Wizard is no less than Rain Man with children, and thus at this point The Wizard turns into a mostly surreal experience. Not totally surreal; we still have to get to the final act for that. Before that happens, our plucky trio has to cross paths with Lucas (Jackey Vinson), the ballingest video game hot shot in the Southwest, who introduces them to the holiness that is the Nintendo Power Glove, and after quietly slipping around in the background, with a little music from Super Mario Bros. 2 here, or a little flash of the NES controller there, the movie explodes into its truest self, as a shameless plug for buying things from Nintendo, playing Nintendo, idealising Nintendo as the pinnacle achievement of human technology and society. For the Power Glove. One of the most notoriously awful video game peripherals ever built. "I love the Power Glove. It's so bad" the boy says with the self-satisfaction of a dreadful yuppie from the era's sex comedies, and it at least half of that is the truest statement in this entire movie.

The shameless wallowing in Nintendo prowess and ownership as the keenest of all social dominance markers, plus Holland and screenwriter David Chisholm's constant inability to treat this kids' movie like a kids movie, forcing the poor child actors into positions of pantomiming adult behavior in their conversations about video games, or sometimes accusing innocent bystanders of being pedophiles ("He! Touched! My! Breast!"), plus the dazzlingly dated costumes and hairstyles, are all enough to make this an extravagantly weird viewing experience, now that we're a generation past its sell-by date. But we're still not to the part where the movie goes off a cliff. That happens at Universal Studios Hollywood, where Video Armageddon, the nation's premier Nintendo gaming competition, is held. For starters, the set of Video Armageddon looks like a combination of the boiler room on an aircraft carrier and an athletic shoe store. Second, the event's announcer (Steven Grives) declaims lines in a manner not compatible with any dialect of English, dancing about and grinning manically like he is the actual Satan and this is some particularly tacky corner of Hell. Third, there's not even a cursory relationship between the proclamations of gameplay and points scored announced over the loudspeaker, and what we can actually see with our own damn eyes.

In short, what is most mystifying about The Wizard isn't that it's a movie set up as a feature-length ad for video games despite being welded onto an emotionally lacerating domestic drama: it's that it's an ad for video games that makes video games look like a peyote hallucination, throwing fragments of game imagery up on screen in ways that make the games themselves seem like jagged, incomprehensible masses of arbitrary movement and the players all puppets in the grip of some helpless madness. It makes videogaming look like the most unpleasant, frenzied activity on Earth, better suited to punishment than entertainment

It's shockingly bad, and coupled with the enormous tonal shifts that happen throughout the movie, it feels basically like The Wizard has an aneurysm right as we're watching it. This is an appallingly jagged and messy film, ugly to look at and saddled with narrative developments that simply happen because the film knows that its end point has to be a video game competition. Everything within it is incongruous to everything else. For those who grew up in the video game culture it depicts, I think it probably serves as a fascinating enough snapshot to serve as a kind of hell-dimension nostalgia trip; but for everyone, its completely batshit insane concept of what human beings are like and what kind of physical spaces the inhabit makes it a thoroughly mesmerising So Bad It's Good spectacular.