Blockbuster History: Male strippers

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Magic Mike XXL continues its predecessor's look at the lives of men who dance dirty for a living. Not the commonest subject in a male gaze-dominated medium, but nor is it the first time this milieu has been plumbed.

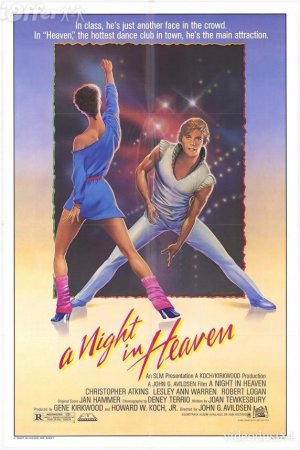

A Night in Heaven is a romantic drama about a community college professor stuck in a dying marriage who has an affair with one of her students after discovering he's a dancer at the local strip club. So obviously it starts off with golden hour shots of Kennedy Space Center. What possible other opening gambit could there be?

So it's a disastrous film, anyway. The splendidly inappropriate opening isn't the reason for that (though it absolutely doesn't help). What it is, though, is perfectly symptomatic of the film's deeply broken sense of self. It's easy to joke, "what kind of movie about strippers opens with several minutes of Cape Canaveral location footage?", but the fact that A Night in Heaven is the answer to that question is telling of how unclear its goals are, as well as its execution of those goals. It is a film divided between the impulse towards smut and towards socially-minded character drama; it is exactly what you get when the Oscar-winning director of Rocky, John G. Avildsen, and the writer of the core material of Nashville, Joan Tewkesbury, find themselves in the business of making a star vehicle for Christopher Atkins, primarily known then and now as the male half of the teen soft-core drama The Blue Lagoon. It's possible to tell, if you hold the film at the right angle, that Avildsen and Tewkesbury had in mind a steady-handed narrative of marital stresses, female desire, and the hard cost of making ethical choices instead of economic ones, and found themselves obliged to readjust everything in the wake of a lead actor whose primary skill was his ability to not wear a shirt. I will say on behalf of the film's novelty that it is maybe the only thing ever filmed that derives virtually all of its dramatic value from the level, complex presence of Lesley Ann Warren.

She plays Faye Hanlon, a skittish-looking teacher of public speaking at a Florida community college and the wife of a bored, boring NASA engineer, Whitney (Robert Logan). For his part, he's facing down an industry in decline, and the company he specifically works for is hunting down Defense Department contracts to make ends meet. This sits poorly with Whitney, who chooses to be laid off rather than work towards what he considers immoral ends, a fact he massages when relating it to his wife. There is surely a deep and interesting subplot involving Whitney to be explored, but A Night in Heaven is resolutely disinterested in it; at 83 minutes long, it could probably afford a little more meat on its bones, but the film is hellbent on getting to the steamy stuff as fast as possible and staying there as long as it dares, and Whitney's existence comes to feel more like an imposition levied on the the film than a possibility for dramatic expansion early in the proceedings.

Faye has a particular student, Rick Monroe (Atkins), who's one of those quintessential movie youths, a brilliant kid with all the potential in the world and no drive to exploit it. So she is compelled to flunk him, on the very day that her sister Patsy (Deborah Rush) is coming to town for a few days of girl bonding, including drinking and a night at Heaven, the local strip club that she found on her last trip. The most popular and lusted-after of all the dancers there is one Ricky the Rocket, and you get zero points for guessing ahead of time that he's the exact same student that Faye just bawled out. She's both mortified and transfixed by his tremendously overt sexual energy, his fearlessness in grinding against patrons and passionately kissing them, and his inappropriately perfect abs. He can tell she's transfixed, and comes along to give her his special treatment; this turns into an intense mutual infatuation that leads her to (gasp!) lie to her husband and (shock and horror!) go back to the strip club to continue ogling. And eventually, it leads to them making tender love. But this was the '80s, and social standards must be maintained, and that means a very abrupt series of plot developments that feel more like the notes for a third act than actual third act. The upshot being that Rick turns out to be a callous little shit.

There are no ways around it: the story is a dog, collecting musty clichés and not even pretending to freshen them up. Avildsen is not without an eye for capturing the sweaty fatigue of environments, and that trick serves him well at multiple points throughout this movie, but it's mostly just spackling a respectable gloss on a tawdry scenario in a tawdry milieu. Which is not, in and of itself, a problem, except that none of the filmmakers seem tremendously interested in making a tawdry movie and that's just not really an applicable strategy here. When the action switches to Heaven, and there's no choice but to make it a tasteless cartoon, it's palpable how weirdly the energy rotates: suddenly the lighting and framing become very self-conscious, like we'll hopefully be so aware of the abstract qualities of the shots that we'll ignore the gyrating men who are, by and large, given curiously unerotic dance moves - witness the Dance of the Kitchen Stools!), or the fever dream hectoring of the Heaven M.C. (Spatz Donovan). His dialogue is the one element of the film that's so incomprehensible that it turns out to be funny - "They'll steam the crease right out of your polyester, ladies!" he leers at one point. "Do you wanna see Ricky take his clooooooothes off?" he later asks, in the kind of hyper-literal statement that suggests children play-acting at strip club management. For unclear reasons, he has been costumed to look like a disco version of the Mad Hatter, but that's just part and parcel of the uncompromising hideousness of the wardrobes. Anna Hill Johnstone, the costume and production design, had an apparent vendetta against the cast, burying Warren especially in costumes so over-the-top in their '80s signifiers that it feels like an Expressionist nightmare about the decade. "You look like a hibiscus in bloom!" coos Patsy to Faye before their first night of debauchery, and that is a thoroughly accurate statement, which certainly would appear to be meant as a compliment.

The strip club sequence is at least appropriately erotic (less so the couple's sexual encounter, which is rushed through like Avildsen - editing as well as directing - just wanted to get it over with), and it's here that Warren really shines. In a lengthy scene that relies entirely on her reaction shots, the actor is able to evoke longing and an immediate wash of guilt at feeling that longing; a desire to stare but also conspicuously trying to make sure that nobody notices her staring; and, uncomplicated by any libidinous urge, a very real sense of confused horror that her professional life and her off-hours gallivanting with Patsy have been blended. It's remarkable acting, and it builds up an aura of goodwill towards the actress attempts to redeem the insufficiently probing remains of Tewkesbury's compromised script, which largely involves adding lots of complicated self-doubt and fear to the surface-level horniness. It's the most human, interesting material in the film, and it's largely wasted, but Warren deserves a lot of credit for the effort.

Nothing was going to actually humanise this material, not with Atkins sucking all the energy out of the room. He's pretty as hell, undoubtedly, but limited to one vapid expression of innocuous self-regard, and prone to making terrible decisions like rolling his eyes so hard during class that it resembles an epileptic fit more than an expression of annoyance, or wearing a nominally flirtatious grin that has virtually no sex in it, just the distant smile of somebody who just remembered the leftover pizza at home. Given his prominence in the story, and the prominence of his body in the film's visual scheme, his callowness, static expressions, and inability to build a solid character are limitations that A Night in Heaven was certainly never going to survive. Warren fights as hard as she can to buck this odds; Avildsen nervously tries to ignore it with needless shots of rockets and a blazingly fast pace; most everybody else just gives up and tries to slap some crap up there onscreen. It's not much of a tribute to the male body or the female libido, and it's an outright joke to pretend that we can cobble together the dog-ends of ignored subplots into a treatise on economic tension in the early years of the Reagan presidency. It's not sordid enough to be decent junk, but the filmmakers gave up on it before had stopped being any kind of junk at all, and other than offering the unusual sight of male objectification in a Hollywood studio picture, there's nothing about it that justifies so much as a sidelong glance.

A Night in Heaven is a romantic drama about a community college professor stuck in a dying marriage who has an affair with one of her students after discovering he's a dancer at the local strip club. So obviously it starts off with golden hour shots of Kennedy Space Center. What possible other opening gambit could there be?

So it's a disastrous film, anyway. The splendidly inappropriate opening isn't the reason for that (though it absolutely doesn't help). What it is, though, is perfectly symptomatic of the film's deeply broken sense of self. It's easy to joke, "what kind of movie about strippers opens with several minutes of Cape Canaveral location footage?", but the fact that A Night in Heaven is the answer to that question is telling of how unclear its goals are, as well as its execution of those goals. It is a film divided between the impulse towards smut and towards socially-minded character drama; it is exactly what you get when the Oscar-winning director of Rocky, John G. Avildsen, and the writer of the core material of Nashville, Joan Tewkesbury, find themselves in the business of making a star vehicle for Christopher Atkins, primarily known then and now as the male half of the teen soft-core drama The Blue Lagoon. It's possible to tell, if you hold the film at the right angle, that Avildsen and Tewkesbury had in mind a steady-handed narrative of marital stresses, female desire, and the hard cost of making ethical choices instead of economic ones, and found themselves obliged to readjust everything in the wake of a lead actor whose primary skill was his ability to not wear a shirt. I will say on behalf of the film's novelty that it is maybe the only thing ever filmed that derives virtually all of its dramatic value from the level, complex presence of Lesley Ann Warren.

She plays Faye Hanlon, a skittish-looking teacher of public speaking at a Florida community college and the wife of a bored, boring NASA engineer, Whitney (Robert Logan). For his part, he's facing down an industry in decline, and the company he specifically works for is hunting down Defense Department contracts to make ends meet. This sits poorly with Whitney, who chooses to be laid off rather than work towards what he considers immoral ends, a fact he massages when relating it to his wife. There is surely a deep and interesting subplot involving Whitney to be explored, but A Night in Heaven is resolutely disinterested in it; at 83 minutes long, it could probably afford a little more meat on its bones, but the film is hellbent on getting to the steamy stuff as fast as possible and staying there as long as it dares, and Whitney's existence comes to feel more like an imposition levied on the the film than a possibility for dramatic expansion early in the proceedings.

Faye has a particular student, Rick Monroe (Atkins), who's one of those quintessential movie youths, a brilliant kid with all the potential in the world and no drive to exploit it. So she is compelled to flunk him, on the very day that her sister Patsy (Deborah Rush) is coming to town for a few days of girl bonding, including drinking and a night at Heaven, the local strip club that she found on her last trip. The most popular and lusted-after of all the dancers there is one Ricky the Rocket, and you get zero points for guessing ahead of time that he's the exact same student that Faye just bawled out. She's both mortified and transfixed by his tremendously overt sexual energy, his fearlessness in grinding against patrons and passionately kissing them, and his inappropriately perfect abs. He can tell she's transfixed, and comes along to give her his special treatment; this turns into an intense mutual infatuation that leads her to (gasp!) lie to her husband and (shock and horror!) go back to the strip club to continue ogling. And eventually, it leads to them making tender love. But this was the '80s, and social standards must be maintained, and that means a very abrupt series of plot developments that feel more like the notes for a third act than actual third act. The upshot being that Rick turns out to be a callous little shit.

There are no ways around it: the story is a dog, collecting musty clichés and not even pretending to freshen them up. Avildsen is not without an eye for capturing the sweaty fatigue of environments, and that trick serves him well at multiple points throughout this movie, but it's mostly just spackling a respectable gloss on a tawdry scenario in a tawdry milieu. Which is not, in and of itself, a problem, except that none of the filmmakers seem tremendously interested in making a tawdry movie and that's just not really an applicable strategy here. When the action switches to Heaven, and there's no choice but to make it a tasteless cartoon, it's palpable how weirdly the energy rotates: suddenly the lighting and framing become very self-conscious, like we'll hopefully be so aware of the abstract qualities of the shots that we'll ignore the gyrating men who are, by and large, given curiously unerotic dance moves - witness the Dance of the Kitchen Stools!), or the fever dream hectoring of the Heaven M.C. (Spatz Donovan). His dialogue is the one element of the film that's so incomprehensible that it turns out to be funny - "They'll steam the crease right out of your polyester, ladies!" he leers at one point. "Do you wanna see Ricky take his clooooooothes off?" he later asks, in the kind of hyper-literal statement that suggests children play-acting at strip club management. For unclear reasons, he has been costumed to look like a disco version of the Mad Hatter, but that's just part and parcel of the uncompromising hideousness of the wardrobes. Anna Hill Johnstone, the costume and production design, had an apparent vendetta against the cast, burying Warren especially in costumes so over-the-top in their '80s signifiers that it feels like an Expressionist nightmare about the decade. "You look like a hibiscus in bloom!" coos Patsy to Faye before their first night of debauchery, and that is a thoroughly accurate statement, which certainly would appear to be meant as a compliment.

The strip club sequence is at least appropriately erotic (less so the couple's sexual encounter, which is rushed through like Avildsen - editing as well as directing - just wanted to get it over with), and it's here that Warren really shines. In a lengthy scene that relies entirely on her reaction shots, the actor is able to evoke longing and an immediate wash of guilt at feeling that longing; a desire to stare but also conspicuously trying to make sure that nobody notices her staring; and, uncomplicated by any libidinous urge, a very real sense of confused horror that her professional life and her off-hours gallivanting with Patsy have been blended. It's remarkable acting, and it builds up an aura of goodwill towards the actress attempts to redeem the insufficiently probing remains of Tewkesbury's compromised script, which largely involves adding lots of complicated self-doubt and fear to the surface-level horniness. It's the most human, interesting material in the film, and it's largely wasted, but Warren deserves a lot of credit for the effort.

Nothing was going to actually humanise this material, not with Atkins sucking all the energy out of the room. He's pretty as hell, undoubtedly, but limited to one vapid expression of innocuous self-regard, and prone to making terrible decisions like rolling his eyes so hard during class that it resembles an epileptic fit more than an expression of annoyance, or wearing a nominally flirtatious grin that has virtually no sex in it, just the distant smile of somebody who just remembered the leftover pizza at home. Given his prominence in the story, and the prominence of his body in the film's visual scheme, his callowness, static expressions, and inability to build a solid character are limitations that A Night in Heaven was certainly never going to survive. Warren fights as hard as she can to buck this odds; Avildsen nervously tries to ignore it with needless shots of rockets and a blazingly fast pace; most everybody else just gives up and tries to slap some crap up there onscreen. It's not much of a tribute to the male body or the female libido, and it's an outright joke to pretend that we can cobble together the dog-ends of ignored subplots into a treatise on economic tension in the early years of the Reagan presidency. It's not sordid enough to be decent junk, but the filmmakers gave up on it before had stopped being any kind of junk at all, and other than offering the unusual sight of male objectification in a Hollywood studio picture, there's nothing about it that justifies so much as a sidelong glance.