The man without a past

A review requested by Julian D, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

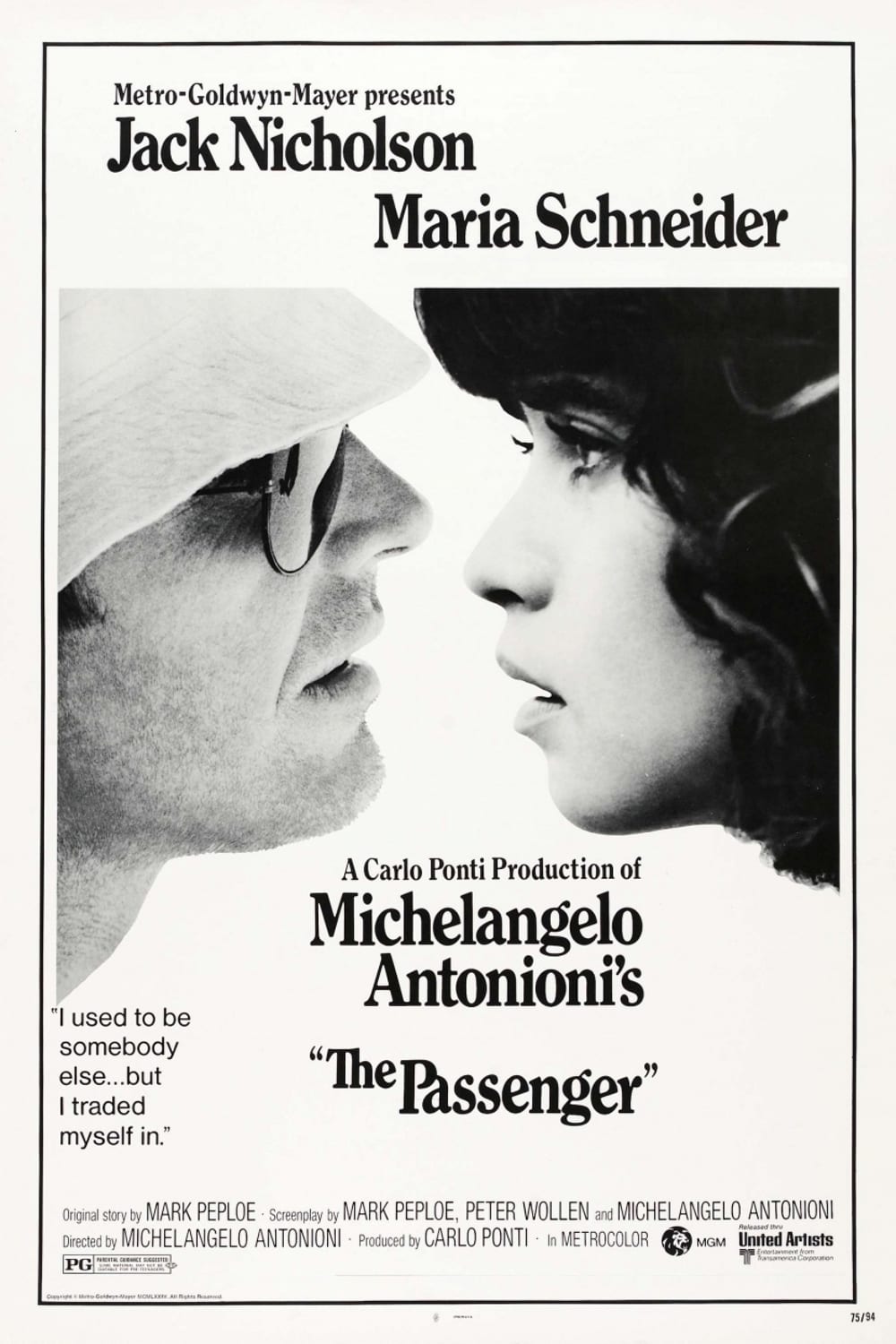

The career of director Michelangelo Antonioni is not the kind that can be neatly summed up in blunt descriptions like "culmination", so I can't use that word to describe his 1975 triumph The Passenger. It does, however, clearly punctuate the director's career: the seventh feature in a chain of hyper-modern masterpieces stretching back to 1960, and his last film before an unintended six-year break that left him an old master whose new films we should dutifully consider even though we probably don't like them very much. A far cry from being one of world cinema's handful of true visionaries, using his movies to anatomise the character of modern society in the same breath and in fact by the same means that he pushed the boundaries of representational, narrative cinema.

In fairness, The Passenger doesn't push boundaries as hard as some of the director's other films. But I think it might very well be his best social document: it dissects and lays bare the paranoias and neuroses of the 1970s even more strikingly than Blowup does the same for the 1960s, and without feeling nearly as dated. The subject is Western Europe and the United States in the aftermath of Vietnam and the social revolutions of the 1960s, blindly hunting for a sense of purpose in a world where Western dominance has been dealt its most serious setbacks of the 20th Century. In the screenplay by the director with Mark Peploe and Peter Wollen), the embodiment of this collapse of identity and purpose is David Locke (Jack Nicholson), a presumably American-born BBC journalist making a documentary on the civil war in Chad. After failing to scrounge up any war or warriors, he loses himself in the Sahara Desert, and walks back to his hotel, where he finds that David Robertson (Charles Mulvehill), the only other white person around, whom Locke has befriended in a vague and noncommittal way, has died. On the spot, Lock decides to swap identities with the dead man, following Robertson's date book to complete whatever task the other man was in the middle of. This turns out to be gun-running. In the meantime, Locke's wife Rachel (Jenny Runacre), has asked her husband's colleague Martin Knight (Ian Hendry) to look for "Robertson", to learn what he knows about "Locke's" death, meaning that Locke finds himself dodging his friend in addition to faking his way around a group of impressively dangerous men who think he has a cache of weapons for him, aided only by an architecture student (Maria Schneider) he meets in Barcelona.

Purely at the level of narrative, there's a lot to unpack, from Locke's indeterminate Anglo/American status, to the complexity and slitheriness of gender roles in the movie (Schneider's character is literally only ever identified as "The Girl", but Locke is in some ways "The Not Even a Man"), to the relationship between Europe and its former colonial holdings bubbling in the background. All of that's not even mentioning the film's most prominent characteristic as a story, which is its merciless portrayal of Locke as a hollow thing, worn down by the speed with which the world is changing and by all available evidence for the worse, to the point that he's a human-shaped signifier of an identity without actually possessing a concrete self. The one word that describes Antonioni's filmmaking is "ennui", and The Passenger is his ennui-est movie; L'avventura and La notte might showcase characters with a complete detachment from the shallow culture containing them, but The Passenger goes one step further, taking away the culture itself.

It's not merely psychological and social vagueness that the film depicts; its indefinite sensibility goes clear to the structure. Antonioni's own stated interpretation of the movie is that it took place over the course of one day, and he and cinematographer Luciano Tovoli filmed it to match (the lighting, mostly natural, grows more and more afternoon-like as it goes along, and it's only in the very last shot that dusk arrives), even if at a practical level it's hard to see how a narrative that moves from Africa to Germany to Barcelona to rural Spain can possibly all take place in ten or twelve hours. Literalism or plausibility aren't the point, though: what is clearly the case, both in the writing and in the visuals, is that The Passenger doesn't seem to have chronology: time moves wrong in the film, in those moments that it moves at all. It is immodestly slow-moving, which has been used a criticism as far back as 1975 (Roger Ebert was an earlier detractor, though he later changed his mind), but of course the fact that the movie is stretched out and not apparently going anywhere in a hurry, or at all, is hardly incidental. Life itself, in The Passenger, isn't really going anywhere; anyplace you go is equally likely to be dead zone of anomie.

The visual scheme Antonioni and Tovoli use to explore this sensibility is broadly familiar from the director's earlier movies: there's a great deal of empty space, whether it's the open sky or featureless walls, against which the characters are set from a far enough distance and low enough in the frame to feel crushed by the size of the composition. The film uses a fairly straightforward and simple color scheme, influenced by the natural earthtones of its locations, the lend a feeling of blanched-out energy, with everything stronger tending to feel oppressive, such as the blue skies or, in the film's most visually and narratively aberrant scene, the toxic-looking neon lights in a metal and concrete hell of an airport. What primarily marks the film as its own thing is the magnificent use of location photography: The Passenger is set mostly in corners of the world and Europe that have a heavy sense of history on them, finally ending in a Spanish town that has tacked elements of modern technology onto streets and buildings that look ancient, hewn from the ground itself in some ways. These are locations bigger than human stories, and Locke seems small and forgotten by the end, finally getting his wish to lose his self figuratively.

Also literally, in the film's incredibly famous penultimate shot, one of the two big showy long takes Antonioni uses (the first is a shocking attempt to bring us into a flashback without cutting, and it's beautifully organic, suggesting the displacement of Locke's thoughts even before the plot starts to make the scope of that displacement clear). It's a long slow track past Locke and through the narrow window of his hotel room, focusing our attention on the geography of the town and the architecture of buildings while its characters die and come to other crises points largely offscreen, the perfect summary of the film's exhausted humanity. Ultimately, it's not even worth showing what happens to the character we've spent two hours getting to not know. Stuff just happens. This is all deeply pessimistic and inhumane, but The Passenger so persuasively argues that pessimism and inhumanity are two of the key traits of Western culture in the 1970s that it doesn't even feel depressing: just "yeah, I guess that's about it". Not a film for a happy, transporting mood, then, but as a diagnosis of purposelessness the film is the most intelligent, engaging kind of misery.

The career of director Michelangelo Antonioni is not the kind that can be neatly summed up in blunt descriptions like "culmination", so I can't use that word to describe his 1975 triumph The Passenger. It does, however, clearly punctuate the director's career: the seventh feature in a chain of hyper-modern masterpieces stretching back to 1960, and his last film before an unintended six-year break that left him an old master whose new films we should dutifully consider even though we probably don't like them very much. A far cry from being one of world cinema's handful of true visionaries, using his movies to anatomise the character of modern society in the same breath and in fact by the same means that he pushed the boundaries of representational, narrative cinema.

In fairness, The Passenger doesn't push boundaries as hard as some of the director's other films. But I think it might very well be his best social document: it dissects and lays bare the paranoias and neuroses of the 1970s even more strikingly than Blowup does the same for the 1960s, and without feeling nearly as dated. The subject is Western Europe and the United States in the aftermath of Vietnam and the social revolutions of the 1960s, blindly hunting for a sense of purpose in a world where Western dominance has been dealt its most serious setbacks of the 20th Century. In the screenplay by the director with Mark Peploe and Peter Wollen), the embodiment of this collapse of identity and purpose is David Locke (Jack Nicholson), a presumably American-born BBC journalist making a documentary on the civil war in Chad. After failing to scrounge up any war or warriors, he loses himself in the Sahara Desert, and walks back to his hotel, where he finds that David Robertson (Charles Mulvehill), the only other white person around, whom Locke has befriended in a vague and noncommittal way, has died. On the spot, Lock decides to swap identities with the dead man, following Robertson's date book to complete whatever task the other man was in the middle of. This turns out to be gun-running. In the meantime, Locke's wife Rachel (Jenny Runacre), has asked her husband's colleague Martin Knight (Ian Hendry) to look for "Robertson", to learn what he knows about "Locke's" death, meaning that Locke finds himself dodging his friend in addition to faking his way around a group of impressively dangerous men who think he has a cache of weapons for him, aided only by an architecture student (Maria Schneider) he meets in Barcelona.

Purely at the level of narrative, there's a lot to unpack, from Locke's indeterminate Anglo/American status, to the complexity and slitheriness of gender roles in the movie (Schneider's character is literally only ever identified as "The Girl", but Locke is in some ways "The Not Even a Man"), to the relationship between Europe and its former colonial holdings bubbling in the background. All of that's not even mentioning the film's most prominent characteristic as a story, which is its merciless portrayal of Locke as a hollow thing, worn down by the speed with which the world is changing and by all available evidence for the worse, to the point that he's a human-shaped signifier of an identity without actually possessing a concrete self. The one word that describes Antonioni's filmmaking is "ennui", and The Passenger is his ennui-est movie; L'avventura and La notte might showcase characters with a complete detachment from the shallow culture containing them, but The Passenger goes one step further, taking away the culture itself.

It's not merely psychological and social vagueness that the film depicts; its indefinite sensibility goes clear to the structure. Antonioni's own stated interpretation of the movie is that it took place over the course of one day, and he and cinematographer Luciano Tovoli filmed it to match (the lighting, mostly natural, grows more and more afternoon-like as it goes along, and it's only in the very last shot that dusk arrives), even if at a practical level it's hard to see how a narrative that moves from Africa to Germany to Barcelona to rural Spain can possibly all take place in ten or twelve hours. Literalism or plausibility aren't the point, though: what is clearly the case, both in the writing and in the visuals, is that The Passenger doesn't seem to have chronology: time moves wrong in the film, in those moments that it moves at all. It is immodestly slow-moving, which has been used a criticism as far back as 1975 (Roger Ebert was an earlier detractor, though he later changed his mind), but of course the fact that the movie is stretched out and not apparently going anywhere in a hurry, or at all, is hardly incidental. Life itself, in The Passenger, isn't really going anywhere; anyplace you go is equally likely to be dead zone of anomie.

The visual scheme Antonioni and Tovoli use to explore this sensibility is broadly familiar from the director's earlier movies: there's a great deal of empty space, whether it's the open sky or featureless walls, against which the characters are set from a far enough distance and low enough in the frame to feel crushed by the size of the composition. The film uses a fairly straightforward and simple color scheme, influenced by the natural earthtones of its locations, the lend a feeling of blanched-out energy, with everything stronger tending to feel oppressive, such as the blue skies or, in the film's most visually and narratively aberrant scene, the toxic-looking neon lights in a metal and concrete hell of an airport. What primarily marks the film as its own thing is the magnificent use of location photography: The Passenger is set mostly in corners of the world and Europe that have a heavy sense of history on them, finally ending in a Spanish town that has tacked elements of modern technology onto streets and buildings that look ancient, hewn from the ground itself in some ways. These are locations bigger than human stories, and Locke seems small and forgotten by the end, finally getting his wish to lose his self figuratively.

Also literally, in the film's incredibly famous penultimate shot, one of the two big showy long takes Antonioni uses (the first is a shocking attempt to bring us into a flashback without cutting, and it's beautifully organic, suggesting the displacement of Locke's thoughts even before the plot starts to make the scope of that displacement clear). It's a long slow track past Locke and through the narrow window of his hotel room, focusing our attention on the geography of the town and the architecture of buildings while its characters die and come to other crises points largely offscreen, the perfect summary of the film's exhausted humanity. Ultimately, it's not even worth showing what happens to the character we've spent two hours getting to not know. Stuff just happens. This is all deeply pessimistic and inhumane, but The Passenger so persuasively argues that pessimism and inhumanity are two of the key traits of Western culture in the 1970s that it doesn't even feel depressing: just "yeah, I guess that's about it". Not a film for a happy, transporting mood, then, but as a diagnosis of purposelessness the film is the most intelligent, engaging kind of misery.