Summer Of Blood: Sci-Fi Horror - A bad case of crabs

In looking at the vast corpus of American movies made between 1945 and 1968 that are typically considered under the umbrella of horror, one thing that leaps to mind is that, almost without exception, they aren't scary. Nor, in a great many cases, does it seem like trying to make them scary was ever the goal. The definition of "horror" is and ought to be broader than just "scary movie", which is why the goofy dipshittery that makes up almost all of American cinema's genre work during the Atomic Age still counts. Still, it's easy to be endlessly frustrated by dumbass giant beasties and unconvincing make-up jobs and the whole nine yards, and wish that any of it was tense enough that a viewer over the age of 9 or 10 might genuinely find it terrifying, or at least creepy, or at least unsettling.

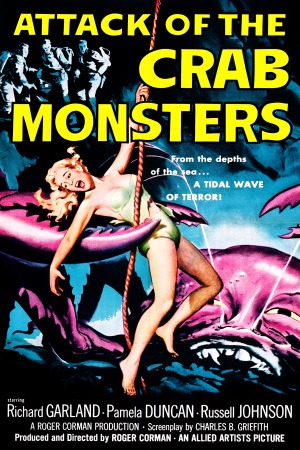

Enter Attack of the Crab Monsters, a 1957 ditty directed and produced by Roger Corman for Allied Artists, from a script he extracted from one of his all-time greatest collaborators, Charles B. Griffith (the legend goes that Corman gave him a title and the directive that every scene should include action, without any of the pauses or layovers responsible for so many itchy asses in so many B-movie audiences, and Griffith came up with all the rest). This was at the very dawn of Corman's career: he'd only been producing for three years and directing for two, and this was just his eleventh feature as director. Because you know what Roger Corman did not do? He did not fuck around. And that applies to his movies as much as to his moviemaking: Attack of the Crab Monsters doesn't meet that platonic ideal of having absolutely no down time, but it gets right to business and it doesn't really waste any more time than it has to in plowing through its brief little running time, hardly more than an hour.

What I'm about to say next will sound stupid, and it is stupid, really. But here it goes: Attack of the Crab Monsters is that one shining exception to the rule I started off with. Look, it has that title, and it has that title for precisely the reason you might guess: there are giant, intelligent, mutant crabs, and they kill people. When we see them, which Corman endeavors to make sure doesn't happen too often or for too long, they look like hell. The characters being hunted by these freaks of nature are serviceable stock types played with a bare minimum of competence, and really not even that in the case of anybody with a strong accent. The shift from the second to the third act is carried on the shoulders of a tower of technobabble so confidently expressed by the script - and delivered by a dude with a fake German accent, to make it even more sciencey - that you can almost fail to notice what staggering, incoherent nonsense it is. And yet, when we know what those crabs are up to, the film manages to become honest-to-God unsettling. On top of the taboo-busting gore scene in the movie, that's enough to make this the one and only micro-budget independent trashy B-horror movie of its generation that I would actually be tempted to claim still sort of works, here in the 21st Century, as horror.

That being said, it still works better as a hilariously chintzy piece of fearless low-grade bad filmmaking. There is, for one thing, that most parsimonious of opening gambits, the stock footage montage - following the surprisingly lovely, hand-painted backdrops for the opening credits, it's ever bit of four minutes before we see anything that was actually shot for Attack of the Crab Monsters. First, we get a luxurious, unhurried array of atomic explosions, then we get a series of effects shots of a boat being swamped that, I suppose may have been original to this movie, but I'd like to think more highly of Corman than that. There's also a portentous Bible quote that makes no sense given the rest of the movie's content, but it involves killing things with water, so it makes sense as far as that goes.

With all that out of the way, we get to meet our team. Six specialists have been sent to a Pacific atoll: the leader is Dr. Karl Weigand (Leslie Bradley), a nuclear physicist, and along with him are geologist James Carson (Richard Cutting), botanist Jules Deveroux (Mel Welles, who never met an ethnic accent he couldn't chomp onto like a pit bull attacking a soup bone), radio man Hank Chapman (Russell Johnson), and a pair of biologists in love, Dale Drewer (Richard Garland) and Martha "Marty" Hunter (Pamela Duncan), because nobody would take a lady scientist seriously if she didn't have a boy's name, duh. They've been assigned two missions: one is to see what has happened to the flora, fauna, and structure of the atoll as a result of radioactive fall-out, and the other is to investigate the disappearance of the last team assigned for the first mission.

Things start going awry almost immediately: the Navy team assigned to protect the scientists suffers a gruesome casualty when Seaman Tate (none other than Charles B. Griffith) falls halfway out of the boat and thrashes around until his crewmates are able to pull him up, and find that his god damned head has been bitten off. We've seen so much more graphic and explicit things than that in the intervening half-century, but when you're watching a black-and-white movie made in this style, you expect a certain level of breezy frivolity: seeing a man's god damned head get bitten off remains just as much of a violation of the unspoken contract between the audience and the movie now as it would have in '57, and it's the first point where the viewer perks up to realise that this is going to be somewhat different than we were led to expect.

Meanwhile, the island is shaking violently at irregular moments, and when a portion of the naval mission prepares to leave, their seaplane explodes without warning. And the discovery of the previous mission's journals indicates that their disappearance had far more violent causes than the "lost in a typhoon" theory the Navy is forwarding. Something is clearly Mysterious and Dangerous on this island, and that's before the echoing, disembodied voice of the previous mission's commander starts drifting across the island at night. As the scientists, radioman, and two remaining seamen (Beach Dickerson and Tony Miller) start investigating, they're taken down at a feverish pace, by an unseen thing with barely glimpsed crablike parts (it's hard to say whether Corman was trying to create a sense of mystery - not a winning strategy in a film with "Crab Monsters" in its title - or simply avoiding showing more of the crabs than he had to), and everybody who vanishes comes back the same night in the form of another echoing voice.

Between the no-nonsense script and the even more no-nonsense direction, Attack of the Crab Monsters blazes by so quickly that its basically a whirlwind of shocking deaths, later to include a dismemberment that makes the first decapitation seem utterly banal. It's a terrific gambit, not least because it prevents us from lingering over the film in a way that reveals its shortcomings, which include at a minimum the snoozy characterisations - Marty is at the center of a romantic triangle that totally refuses to land - and the fact that the film has the indication of a story more than the actual details and fullness that really are a story. Or how much the setting does not resemble a Pacific atoll beyond the presence of an ocean.

Also, the film's pace serves a more abstract function: it keeps us out of balance, and makes us more susceptible to the eeriness inherent in the film's best element, those disembodied voices. It's a cheap trick (they're all cheap tricks), but just modifying the sound to give it a hollow, metallic edge makes those voices feel truly wrong on an instinctual level, even before we learn exactly what's causing them. The reveal of that is another one of the film's most unsettling elements, though it takes some wading through the worst of the pseudoscience to get there - the crabs, who have been nuked not just into gigantic size, but also into a quantum state where they are made of pure energy, or whatever it's supposed to be, can absorb a person's identity by eating their head. It is so dumb as the defy believe, but there's also something skin-crawling about the matter-of-fact way the film drops it in, a form of body horror before there was body horror. "Once they were men; now they're land crabs" is a loopy bit of dialogue, but it speaks to a sick notion, much bleaker than the average for a giant nuclear monster picture. Especially as Griffith lays the groundwork by referencing the real-life tendency of land crabs to devour wounded humans left unattended on the beach.

The film foregrounds none of this: it's all buried beneath some delightfully campy idiocy typical of the genre, with that extra spin of dazzling showmanship that separated Corman from all of his peers. He wasn't all the way there, yet, except in his wisdom in showing just enough of just the right parts of the crabs - when he can't keep hiding, and we can see their big cow eyes, it's all over but the laughing. It's a sturdy piece of B-movie filmmaking with a crowd-pleasing energy that's much more enjoyable than most other films on this model. It's a terrible, terrible movie - any film that gives its giant crab monster a threatening climactic line like "So, you have wounded me, and I must grow a new claw. Well and good, for I can do it in a day. But will you grow new lives when I have taken yours from you?" isn't ever going to be anything but terrible. But it is the zesty, vital kind of terrible, and this most dodgy and dimwitted of all subgenres was rarely more fun in its all-encompassing badness, or more effective in mining something memorable out of its stock elements.

Body Count: 9, though it is at least possible that we didn't see everybody who was on that seaplane.