Summer of Blood: Horror Gets Mean - They're dead, they're all messed up

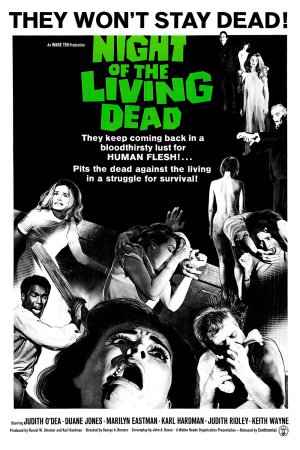

As an inveterate lover of making grand historical movements out of molehills, it pleases me to know end that it's possible to pinpoint the exact year that American genre films switched from the classical to the modern age: 1968. In that year, both science fiction and horror made an immense, revolutionary leap forward, with a pair each of movies that made it simply impossible to take seriously the genre as it had developed to that point. Science fiction witnessed the radical visual effects and thematic density of 2001: A Space Odyssey, as well as the philosophically serious treatment of seemingly frivolous subject matter in Planet of the Apes (which for good measure also boasts one of cinema's all-time most audacious original musical scores). Horror, which we're here to discuss now, had the very grown up, emotionally and psychologically grounded urban realism of Rosemary's Baby, which we'll be looking at elsewhere. Right now, we're just here to talk about neophyte director George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead, co-written with John A. Russo, the movie that pioneered the most stomach-churning decency-violating taboo-busting violence that English-speaking filmgoers had ever seen. And if there exists, prior to 1968, any film in all the world with anything like the pure visceral grotesqueness of NotLD, I have absolutely not seen nor heard of it.

The film did not, to be clear, invent the notion of harder-than-usual violence as a selling point. As long as Britain's Hammer Film had been in existence, one of its biggest calling cards was a level of gruesome content beyond anything the quivering Yanks were likely to produce, and five years before Romero and company hit the scene, Herschell Gordon Lewis's Blood Feast was sold on the promise of literally nothing but the bloodiness of its death scenes, and is usually cited as the first movie to so centrally fixate on depicting gore. But Night of the Living Dead is in a different league from those: indeed, the new wave of violent horror that it kicked off served in no small part to kill of Hammer, which went from looking like the nastiest, savviest stuff you could ever scrounge up to being utterly square and safe almost in the blink of an eye. NotLD had the good fortune to come out in the exact year that the old Production Code was scrapped in favor of the vastly more permissive MPAA ratings system, which explains most of it, honestly. Some film was going to fill this spot in the movie ecosystem.

But NotLD isn't just "some" film. Romero didn't merely use his new freedom to shock with unimagined levels of blood and call that a good day's work, as Lewis undoubtedly would have in the same position. As would quickly become his wont, the director was hellbent on using his movie to carve open the guts of American culture, using violence and even the horror genre itself as a tool rather than an end. That's by far the most upsetting, vicious element of the film, even if its initial reception was hung up (fairly) on its explicitness. Decades later, the most violent moment in the whole movie, an orgy of cannibalism in which the innards of two victims burning to death in a truck are paraded around by a small army of zombies, looks modest and quaint, the kind of thing that would pass uncut on a basic cable network. It might actually be the least effective part of the movie to modern eyes, for while we've lapped the effects work several times over, virtually everything else about it remains not just fresh and mostly untouched by copycats, but in some ways acutely dangerous. This is a movie that knows what the rules are, and it breaks every one it can; it has an astonishing capacity, otherwise unknown to me in horror of this age, to seriously fuck with your head.

Should it be the case that you do not know the plot of this most iconic and necessary of horror milestones, let me give you the rundown: siblings Barbra (Judith O'Dea) and Johnny (Russell Streiner) have driven hours into the Pennsylvania countryside to leave a cross of flowers on their father's grave at their bedridden mother's request. Enjoying the chance to taunt his easily-spooked sister, Johnny points to an oddly shuffling man (Bill Hinzmen) and jokingly suggests that he's coming to kill them. The joke's on Johnny: that's exactly what the man is up to, and Johnny ends up with a broken neck while Barbra flees to a farmhouse some ways distant. Her explorations lead her to a gruesomely stripped corpse, and she effectively blacks out from that point forward, but the movie is taken over by several other survivors. First comes Ben (Duane Jones), hoping to find gasoline for his truck, who secures the building from the suddenly numerous armies of unspeaking violent humans; and then it turns out that five others have already taken refuge in the cellar: young couple Tom (Keith Wayne) and Judy (Judity Ridley), and the Cooper family, blowhard Harry (Karl Hardman), his plainly resentful wife Helen (Marilyn Eastman), and their badly sick daughter Karen (Kyra Schon). The seven prepare to dig in and try to survive the night, but a power struggle almost immediately begins between Ben, who wants to stay upstairs and defend the home, and Harry, who wants to bar everyone in the cellar and hope that the authorities come along soon. Of course, the authorities are a bit busy right now: as the characters learn when they turn on the TV and radio, the eastern third of the United States has been overrun by a plague of recently-deceased bodies reviving as man-eating ghouls, and other than some vague notion about space radiation, nobody has a clue why.

The key element of Romero's ...of the Dead films (there have been six) is already fully-formed in this first outing: when presented with a stressful and deadly situation that can be fairly easily survived through clear thinking and cooperation, human beings will much prefer to fall into in-fighting and mutual distrust, and thereby fall prey to an enemy that, rationally, doesn't have much going for it. The reanimated corpses are slow, clumsy, and despite some rudimentary ability to use tools and solve basic problems, not apparently very bright. The reason for the deaths that occur in that farmhouse are, each and every one, because Ben and Harry can't compromise.

As is the most spectacularly unoriginal observation I could possibly make, Night of the Living Dead serves as a parable of 1960s America, on at least two fronts. The one that smacks you alongside the head and then asks why your face has a handprint on it is the perilous state of race relations in the winding down days of the civil rights movement: Duane Jones was the first African-American protagonist of a horror movie in the States. Romero has consistently, to my knowledge, denied that he did this on purpose, and he only cast Jones because he was the best actor to audition for the part. Which is plausible on the grounds that Jones is far and away the best actor in the completed movie. But it is beyond plausibility that a filmmaker casting a role in 1967 in the United States would put an African-American actor in a leading role - especially this leading role - and have not a single thought cross his mind that there might potentially be some kind of socio-political reading applied to it. The film never blinks on it, mind you: while the driving force of the whole deal is the increasingly enraged hatred Harry feels towards Ben, there's not one line of dialogue nor even the slightest gesture in Hardman's performance that suggests racism is behind any of it. Still, symbolism will elbow its way in no matter what, and the sight of a schlubby, slumped-over, sweaty white guy spitting invective and bristling as a black guy tells him what to do absolutely suggests certain things in a 1968 context (and, I am very sorry to say, in a 2015 context) that are impossible to overlook. Much as the film's punishingly bleak final moments don't inherently rely on race for the narrative to make perfect sense, but SPOILERS IF YOU ACTUALLY DON'T KNOW HOW THIS ENDS roving gangs of white cops shooting at barely-seen minorities without stopping to wonder if they deserve to be murdered or not can't avoid connoting things that are angry and ugly about the way society works (and, I am outrageously sorry to say, possibly more so in 2015 than in 1968).

But the bigger thing that's going on, undoubtedly, is that this story about people ending up in an unsolvable situation and dying for no good reason, but doing an awesome job of blaming each other for their predicament is a curdled, cynical parable for the Vietnam era. As a billion people have already pointed out before me, NotLD paints a profoundly hopeless picture of smart people getting out of quagmires for one particular reason, and it not only gives the film more thematic heft, it works tremendously well to its benefit as a horror movie. Simply put, everything we know about storytelling, and everything we know about unpacking visuals in narrative cinema, tells us that Ben is the hero and he knows what to do, and Harry is a selfish, cowardly asshole whose bullying attitude puts him securely in the wrong. Jones's performance is steady and full of varied, vibrant emotions (the determined way he recites his backstory is beautiful, making it clear that he's trying to put an upbeat vibe into the room or at least distract himself), while Hardman spouts lines in a petulant whine; Hardman is lit and framed to look like a bipedal tower of flop sweat. And yet Ben's plan kills everybody. Follow the rules, be sensible, and use calm logic, the film indicates, and you're just going to make everything worse. As a viewer watching a genre film, that callous violation of the basic contract we make with every movie is acutely upsetting, a daring perversity that almost a half century later has only rarely been matched; as a commentary on the nature of humanity, it is pessimistic unto nihilism, but don't look to me for the argument that it doesn't fit the facts of the world of '67 and'68 pretty neatly.

Strictly as a movie, and not as a cutting political statement, NotLD makes quite a nasty habit of breaking trust with our expectations, and if that leads to some moments which are hard to take here in the 2010s, I can't even guess what it must have been like to experience them in '68. The film lets us know right away that it plans to insult conventional decency: the very first thing we encounter is Johnny bitching about having to decorate a grave, a pointless act of empty symbolism. It's a moment that echoes on the far side of a film with a TV talking head mercilessly declaring that the time for romanticising death is over: if a loved one dies, you had damned well better desecrate their corpse on the spot and make absolutely certain they don't come back to eat you, and bullshit funerary customs are now an unavailable luxury. And there's the other echo, in a moment that has lost not an ounce of its power to devastate, when the most essential family tie of mother and child is corrupted and perverted in a scene that should be ridiculously over-emphasised, with sound editing that goes so far overboard in exaggerating the horror of the moment that it's dissociative with anything happening onscreen. And yet no matter what mood I'm in or how many times I see the movie, that's the scene where it feels like Romero and Russo are playing with actual fire, and I'm seeing something so cruelly transgressive that it flattens me every single time.

Even in its more conventional aspects - and there are not many of those - the film is a superlative piece of construction. The hook is simplicity itself: pare away the new conception of the mindless undead as a biological plague (a notion Romero confesses to having lifted intact from Richard Matheson's I Am Legend) and cannibal holocaust, and this is a straightforward "stressed out cast trapped in small location tries to survive through the night" chamber piece. Though fairness requires me to admit that it's a story model that didn't really exist before this, not in such a purified state. But withing that limited framework, Romero and crew do a fantastic job of manipulating tension in the simplest ways. The more that we're meant to be frazzled and unnerved, the more acute the angle of the camera, either on its side or tilting up and down; and while this is going on, the compositions become tighter and more cluttered. It's inelegant, but it's not really trying to be anything else. And while the use of stock music is to be bemoaned as the necessary evil of a bargain-basement production (the only sign of it, in fact; this is a master class in making a hell of a lot from good implication, repressive camera angles, and a whole lot of game extras working for a couple of nights), the use of music, if not always the specific notes melodies at every moment, is nicely timed to throw us back and forth like a rag doll.

The film is a superlative machine for making you feel ragged, terrified, and bewildered by the essential hopelessness of the universe, but it does ultimately have a distinct mechanical feel in a lot of ways, I admit this. A huge reason for this is that out of seven characters, only Ben and Harry are in any way interesting (Romero's screenplay for the 1990 remake attempted to make Barbra a stronger character than the shell-shocked babbler she is here, which is at least one thing to appreciate about that film), and Jones gives the only performance of any real meat - which isn't a flaw necessarily, Hardman being one-night and inorganic contributes to our inability to connect with Harry and the film gets a lot of mileage from that. Still, an engaging story of humans it ain't, even though it's quite the fable of humankind.

There are also inevitable shortcomings that come with the minute scale of the shoot: small but distinct continuity errors (the newscast, for example, shows an interview in broad daylight that, by the film's internal continuity, had to have taken place after dark), takes that feel like the actor lost focus for a second and found it again, some obvious Foley work. But whatever Night of the Living Dead gets somewhat wrong is negligible in the face of how much it gets right: inventing a new kind of horror movie and a new kind of monster - though Romero never uses the word "zombie" and probably wasn't even in those terms, the film's success buried the old White Zombie-style zombie picture beyond recovery, and even a transitional effort like the 1966 Hammer production The Plague of the Zombies looks woefully old-fashioned in comparison. It is a bleak movie to usher in a bleak decade, cinema's all-time most embittered period in horror and mainstream cinema alike; it is one of the handful of truly transformational individual films in the medium's history, and a gripping, intense viewing experience on top of it. This is as vital of a viewing experience as horror offers.

Body Count: 8, defined solely as those characters that we see alive in the traditional sense who are later killed and/or turned.

The film did not, to be clear, invent the notion of harder-than-usual violence as a selling point. As long as Britain's Hammer Film had been in existence, one of its biggest calling cards was a level of gruesome content beyond anything the quivering Yanks were likely to produce, and five years before Romero and company hit the scene, Herschell Gordon Lewis's Blood Feast was sold on the promise of literally nothing but the bloodiness of its death scenes, and is usually cited as the first movie to so centrally fixate on depicting gore. But Night of the Living Dead is in a different league from those: indeed, the new wave of violent horror that it kicked off served in no small part to kill of Hammer, which went from looking like the nastiest, savviest stuff you could ever scrounge up to being utterly square and safe almost in the blink of an eye. NotLD had the good fortune to come out in the exact year that the old Production Code was scrapped in favor of the vastly more permissive MPAA ratings system, which explains most of it, honestly. Some film was going to fill this spot in the movie ecosystem.

But NotLD isn't just "some" film. Romero didn't merely use his new freedom to shock with unimagined levels of blood and call that a good day's work, as Lewis undoubtedly would have in the same position. As would quickly become his wont, the director was hellbent on using his movie to carve open the guts of American culture, using violence and even the horror genre itself as a tool rather than an end. That's by far the most upsetting, vicious element of the film, even if its initial reception was hung up (fairly) on its explicitness. Decades later, the most violent moment in the whole movie, an orgy of cannibalism in which the innards of two victims burning to death in a truck are paraded around by a small army of zombies, looks modest and quaint, the kind of thing that would pass uncut on a basic cable network. It might actually be the least effective part of the movie to modern eyes, for while we've lapped the effects work several times over, virtually everything else about it remains not just fresh and mostly untouched by copycats, but in some ways acutely dangerous. This is a movie that knows what the rules are, and it breaks every one it can; it has an astonishing capacity, otherwise unknown to me in horror of this age, to seriously fuck with your head.

Should it be the case that you do not know the plot of this most iconic and necessary of horror milestones, let me give you the rundown: siblings Barbra (Judith O'Dea) and Johnny (Russell Streiner) have driven hours into the Pennsylvania countryside to leave a cross of flowers on their father's grave at their bedridden mother's request. Enjoying the chance to taunt his easily-spooked sister, Johnny points to an oddly shuffling man (Bill Hinzmen) and jokingly suggests that he's coming to kill them. The joke's on Johnny: that's exactly what the man is up to, and Johnny ends up with a broken neck while Barbra flees to a farmhouse some ways distant. Her explorations lead her to a gruesomely stripped corpse, and she effectively blacks out from that point forward, but the movie is taken over by several other survivors. First comes Ben (Duane Jones), hoping to find gasoline for his truck, who secures the building from the suddenly numerous armies of unspeaking violent humans; and then it turns out that five others have already taken refuge in the cellar: young couple Tom (Keith Wayne) and Judy (Judity Ridley), and the Cooper family, blowhard Harry (Karl Hardman), his plainly resentful wife Helen (Marilyn Eastman), and their badly sick daughter Karen (Kyra Schon). The seven prepare to dig in and try to survive the night, but a power struggle almost immediately begins between Ben, who wants to stay upstairs and defend the home, and Harry, who wants to bar everyone in the cellar and hope that the authorities come along soon. Of course, the authorities are a bit busy right now: as the characters learn when they turn on the TV and radio, the eastern third of the United States has been overrun by a plague of recently-deceased bodies reviving as man-eating ghouls, and other than some vague notion about space radiation, nobody has a clue why.

The key element of Romero's ...of the Dead films (there have been six) is already fully-formed in this first outing: when presented with a stressful and deadly situation that can be fairly easily survived through clear thinking and cooperation, human beings will much prefer to fall into in-fighting and mutual distrust, and thereby fall prey to an enemy that, rationally, doesn't have much going for it. The reanimated corpses are slow, clumsy, and despite some rudimentary ability to use tools and solve basic problems, not apparently very bright. The reason for the deaths that occur in that farmhouse are, each and every one, because Ben and Harry can't compromise.

As is the most spectacularly unoriginal observation I could possibly make, Night of the Living Dead serves as a parable of 1960s America, on at least two fronts. The one that smacks you alongside the head and then asks why your face has a handprint on it is the perilous state of race relations in the winding down days of the civil rights movement: Duane Jones was the first African-American protagonist of a horror movie in the States. Romero has consistently, to my knowledge, denied that he did this on purpose, and he only cast Jones because he was the best actor to audition for the part. Which is plausible on the grounds that Jones is far and away the best actor in the completed movie. But it is beyond plausibility that a filmmaker casting a role in 1967 in the United States would put an African-American actor in a leading role - especially this leading role - and have not a single thought cross his mind that there might potentially be some kind of socio-political reading applied to it. The film never blinks on it, mind you: while the driving force of the whole deal is the increasingly enraged hatred Harry feels towards Ben, there's not one line of dialogue nor even the slightest gesture in Hardman's performance that suggests racism is behind any of it. Still, symbolism will elbow its way in no matter what, and the sight of a schlubby, slumped-over, sweaty white guy spitting invective and bristling as a black guy tells him what to do absolutely suggests certain things in a 1968 context (and, I am very sorry to say, in a 2015 context) that are impossible to overlook. Much as the film's punishingly bleak final moments don't inherently rely on race for the narrative to make perfect sense, but SPOILERS IF YOU ACTUALLY DON'T KNOW HOW THIS ENDS roving gangs of white cops shooting at barely-seen minorities without stopping to wonder if they deserve to be murdered or not can't avoid connoting things that are angry and ugly about the way society works (and, I am outrageously sorry to say, possibly more so in 2015 than in 1968).

But the bigger thing that's going on, undoubtedly, is that this story about people ending up in an unsolvable situation and dying for no good reason, but doing an awesome job of blaming each other for their predicament is a curdled, cynical parable for the Vietnam era. As a billion people have already pointed out before me, NotLD paints a profoundly hopeless picture of smart people getting out of quagmires for one particular reason, and it not only gives the film more thematic heft, it works tremendously well to its benefit as a horror movie. Simply put, everything we know about storytelling, and everything we know about unpacking visuals in narrative cinema, tells us that Ben is the hero and he knows what to do, and Harry is a selfish, cowardly asshole whose bullying attitude puts him securely in the wrong. Jones's performance is steady and full of varied, vibrant emotions (the determined way he recites his backstory is beautiful, making it clear that he's trying to put an upbeat vibe into the room or at least distract himself), while Hardman spouts lines in a petulant whine; Hardman is lit and framed to look like a bipedal tower of flop sweat. And yet Ben's plan kills everybody. Follow the rules, be sensible, and use calm logic, the film indicates, and you're just going to make everything worse. As a viewer watching a genre film, that callous violation of the basic contract we make with every movie is acutely upsetting, a daring perversity that almost a half century later has only rarely been matched; as a commentary on the nature of humanity, it is pessimistic unto nihilism, but don't look to me for the argument that it doesn't fit the facts of the world of '67 and'68 pretty neatly.

Strictly as a movie, and not as a cutting political statement, NotLD makes quite a nasty habit of breaking trust with our expectations, and if that leads to some moments which are hard to take here in the 2010s, I can't even guess what it must have been like to experience them in '68. The film lets us know right away that it plans to insult conventional decency: the very first thing we encounter is Johnny bitching about having to decorate a grave, a pointless act of empty symbolism. It's a moment that echoes on the far side of a film with a TV talking head mercilessly declaring that the time for romanticising death is over: if a loved one dies, you had damned well better desecrate their corpse on the spot and make absolutely certain they don't come back to eat you, and bullshit funerary customs are now an unavailable luxury. And there's the other echo, in a moment that has lost not an ounce of its power to devastate, when the most essential family tie of mother and child is corrupted and perverted in a scene that should be ridiculously over-emphasised, with sound editing that goes so far overboard in exaggerating the horror of the moment that it's dissociative with anything happening onscreen. And yet no matter what mood I'm in or how many times I see the movie, that's the scene where it feels like Romero and Russo are playing with actual fire, and I'm seeing something so cruelly transgressive that it flattens me every single time.

Even in its more conventional aspects - and there are not many of those - the film is a superlative piece of construction. The hook is simplicity itself: pare away the new conception of the mindless undead as a biological plague (a notion Romero confesses to having lifted intact from Richard Matheson's I Am Legend) and cannibal holocaust, and this is a straightforward "stressed out cast trapped in small location tries to survive through the night" chamber piece. Though fairness requires me to admit that it's a story model that didn't really exist before this, not in such a purified state. But withing that limited framework, Romero and crew do a fantastic job of manipulating tension in the simplest ways. The more that we're meant to be frazzled and unnerved, the more acute the angle of the camera, either on its side or tilting up and down; and while this is going on, the compositions become tighter and more cluttered. It's inelegant, but it's not really trying to be anything else. And while the use of stock music is to be bemoaned as the necessary evil of a bargain-basement production (the only sign of it, in fact; this is a master class in making a hell of a lot from good implication, repressive camera angles, and a whole lot of game extras working for a couple of nights), the use of music, if not always the specific notes melodies at every moment, is nicely timed to throw us back and forth like a rag doll.

The film is a superlative machine for making you feel ragged, terrified, and bewildered by the essential hopelessness of the universe, but it does ultimately have a distinct mechanical feel in a lot of ways, I admit this. A huge reason for this is that out of seven characters, only Ben and Harry are in any way interesting (Romero's screenplay for the 1990 remake attempted to make Barbra a stronger character than the shell-shocked babbler she is here, which is at least one thing to appreciate about that film), and Jones gives the only performance of any real meat - which isn't a flaw necessarily, Hardman being one-night and inorganic contributes to our inability to connect with Harry and the film gets a lot of mileage from that. Still, an engaging story of humans it ain't, even though it's quite the fable of humankind.

There are also inevitable shortcomings that come with the minute scale of the shoot: small but distinct continuity errors (the newscast, for example, shows an interview in broad daylight that, by the film's internal continuity, had to have taken place after dark), takes that feel like the actor lost focus for a second and found it again, some obvious Foley work. But whatever Night of the Living Dead gets somewhat wrong is negligible in the face of how much it gets right: inventing a new kind of horror movie and a new kind of monster - though Romero never uses the word "zombie" and probably wasn't even in those terms, the film's success buried the old White Zombie-style zombie picture beyond recovery, and even a transitional effort like the 1966 Hammer production The Plague of the Zombies looks woefully old-fashioned in comparison. It is a bleak movie to usher in a bleak decade, cinema's all-time most embittered period in horror and mainstream cinema alike; it is one of the handful of truly transformational individual films in the medium's history, and a gripping, intense viewing experience on top of it. This is as vital of a viewing experience as horror offers.

Body Count: 8, defined solely as those characters that we see alive in the traditional sense who are later killed and/or turned.