Old soldiers never die

A review requested by Liz, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

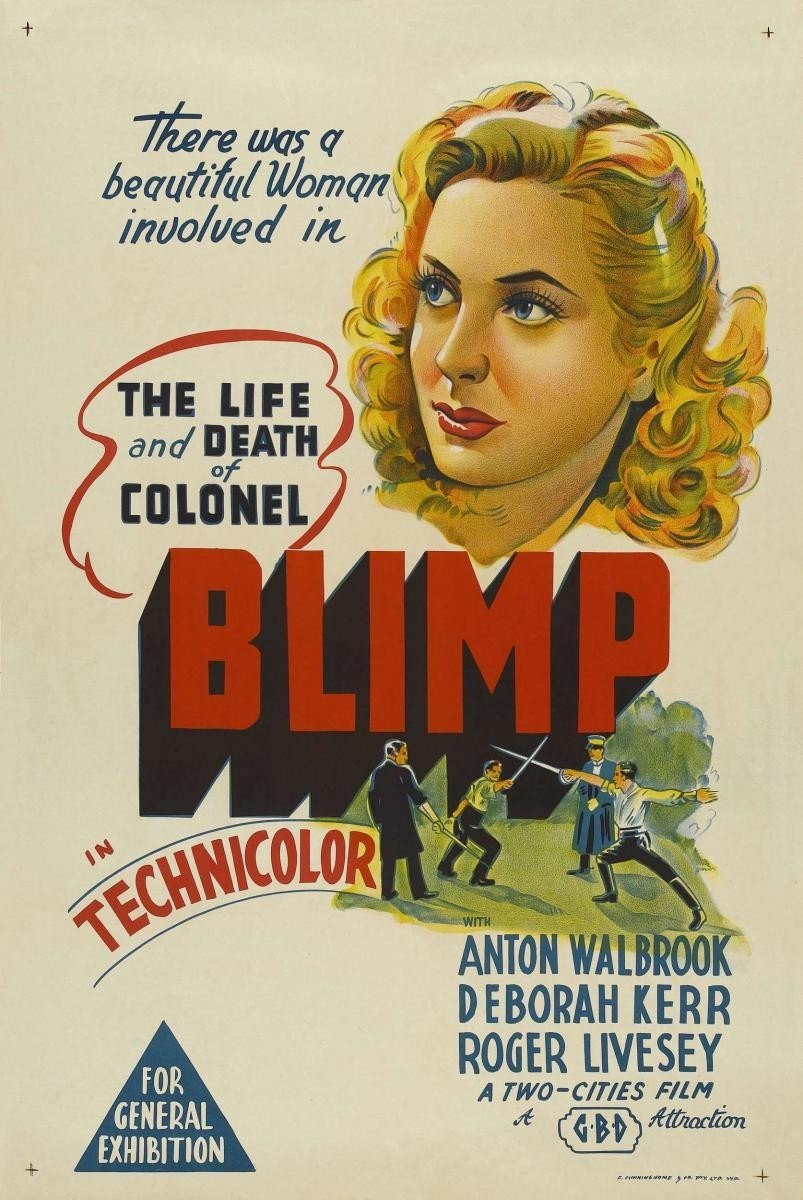

The body of work created by the filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (credited equally as writers, directors, and producers, though it's generally understood that Powell was more the director, while Pressburger was more the writer and producer) is arguably the high water mark of all British cinema, and their 1943 collaboration The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is maybe the most essentially, urgently British of the 21 films they made together. It is probably the most epic and ambitious in scale and intention: it's a World War II propaganda film with a real message on its mind other than the usual "We can do it if we stick together!" cheerleading typical of its generic bedfellows, that bases its analysis of what the people of the British isles could and should do to stave off the Nazi threat in a long-form study of military history spanning nearly half of a century. It does this in the body of one immaculately conservative soldier named Major-General Clive Wynne-Candy (Roger Livesey, flawlessly playing a brash youth and a puffed-up old man so distinctly that it's almost difficult to believe that they were both a 37-year-old actor), inspired in his personality and appearance by Colonel Blimp, the star of a satirical comic strip by David Low, but infinitely more expansive in personality; and it does this in the form of what must absolutely be the most excitingly shot British production I can personally name up to that point in history, the moment that Powell's directorial style snapped into focus and provided a visual means of expression that's neither exactly Hollywood nor exactly European. It would not, for my taste, remain the best production released under the banner of the Archers (Powell & Pressburger's independent company, through which they'd make all of their films until 1957), with their post-war efforts A Matter of Life and Death and The Red Shoes eclipsing it in stylistic and structural complexity, and overall excellence, respectively. But it's more radical than they are, inventing out of thin air what they (and the rest of the Archers' output) would thereupon refine and build from.

The movie begins and ends in 1942, where Wynne-Candy is an old and slightly ridiculous ex-Army figure, spending his retirement advising and training the Home Guard. He's introduced as the butt of something halfway between a prank and a political demonstration: the evening afternoon before a war game is meant to start at midnight, brash young lieutenant "Spud" Wilson (James McKechnie) breaks into the Turkish bath where Wynne-Candy and many other old Army outcasts spend their hours, capturing the old man and winning the war game before it begins. This triggers a spirited argument between the two warriors, Wilson insisting that old, traditional conservative men like Wynne-Candy aren't merely out of touch, but acutely dangerous in this new sort of warfare. Chastened and annoyed, the old man finds himself drifting into an extended flashback that rewinds to that same Turkish bath, 41 years prior, when he was just Lieutenant Clive Candy, on leave from the Second Boer War - the flawlessly-executed trick by which a youthful body double substitutes for Livesey in his old age makeup while the camera manages to get slightly too far ahead of the character is the first of many coups du cinéma in the film, seamlessly blurring past and present into one discontinuous chronology that doubles as the first leg in the filmmakers' argument about the way that the past informs the present.

The remainder of the film is largely concerned with three movements, one during the Boer War, one in the days immediately following the First World War, and one in the early years of the Second World War, bringing us finally back to the morning of the day on which we met Candy. In each of these segments, we also see Candy's developing relationship with Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), a German officer with whom Candy duels in 1901, while he's in Berlin on an unofficial mission to defuse an anti-British propaganda effort. And we see as well his encounters with three young women who all look exactly alike, for the good reason that they're all played by Deborah Kerr: Edith Hunter, an idealist who obviously loves Candy but ends up marrying Kretschmar-Schldorff; Barbara Wynne, a pragmatic nurse who marries Candy despite his being much older; and Angela "Johnny" Cannon, who serves as his sharp-tongued assistant and driver as he works with the Home Guard, and ends up helping to bridge the gulf between the honorably conservative Brit and the honorably conservative German while their countries prepare to go to war.

While each sequence is hung on a single driving narrative spine, the overall impression is of a movie that meanders its way through history over the course of two hours and 43 minutes (the film was cut twice before being restored to its full length in 1983; a more thorough clean-up job restoring the vivid colors was completed in 2011), and yet never feels like there's a single sagging moment or unnecessary layover. The script is thoughtful and decisive, crisply marking down character beats for the actors to later flesh in, and presenting symbolic conflicts which feel so personal in their execution that the degree to which this is all a metaphorical satire of British military etiquette hardly gets in the way of what a perfect study of individual lives it is as well. And I will give it this above even A Matter of Life and Death and The Red Shoes and all the rest: it is very possible that this is the best-written of the Archers' film, structurally, psychologically, and thematically. As it cycles back into 1942 and presents its message that men of Candy's era, for all their dignity and experience and intelligence, aren't equipped to fight a war against the systemic evil represented by Nazi Germany, the film generates a fierce passion about its topic mixed with affection, deep and rich and abiding affection, for the characters it's consigning to history. For something with such a serious subject, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp moves forward with enormous generosity and a great deal of fresh, bubbly humor - indeed, it is as much a comedy as otherwise, growing gradually darker towards the end.

The beautiful writing goes hand in hand with exemplary filmmaking technique that draws it out and works it into the visual bones of the movie. It is supremely well made, and not always because it draws attention to itself: one of the most perfect sequences in the movie consists of a camera staring at Walbrook's face as he quietly delivers a deep, probing monologue, pushing into a close-up, and then backing away again. It's so simple as to be virtually anti-cinematic, but it's exactly what the movie needs, both for the integrity of the monologue, and the place it occupies near the very beginning of the 1939 sequence; it promises the seriousness and mournful intimacy that the rest of the film will largely concern itself with, in opposition to the more bright material of the first two-thirds.

Frequently, though, the style is so great precisely because it makes itself felt. There is the comic audacity of the first transition from the Boer War to the First World War, a montage of mounted animal heads representing Candy's somewhat bloodthirsty approach to leisure time until he can get back to business (ending with the nihilistic joke of a Germany army helmet with the descriptive plaque "Hun - Flanders, 1918"); there is the bleak poetry of the second transition from the First World War to the Second, with the Wynne-Candy family album skipping through blank page after blank page following the newspaper clipping of Barbara's death. And there is the richness and moral complexity of the individual images, shot in glowing Technicolor to accentuate the vibrancy of military uniforms and upper class splendor in sharp contrast to default setting of drab earth tones, suggesting throughout (but especially in the Boer War sequence) that the pageantry of the British military and the pride of men like Candy, however handsome and captivating, is also chintzy and surface-level, all glamor without soul. Or consider the way that Powell presents the duel that takes up a huge portion of the first act: the opening preparations are contained within a hollow wide shot of a gymnasium, like a dead cathedral of Continental honor; the actual duel starts during a high-angle crane shot that backs away as Allan Gray's jaunty score kicks in, suggesting a perverse ballet, all part of the theatricality of the lives it presents, before dissolving into a snowstorm.

The visuals are, throughout, sardonic and witty, detached with just enough ghostliness that they feel appropriately out of time and yet anchored by the superbly expressive faces of Livesey and Walbrook that the immediate feeling of the characters' lives is always front and center. The images are satiric while the script is utterly sincere, and the structure is moody and weary while the energy of each scene and each performance is fiery and urgent, communicating with an intensity that could only driven by enthusiastic and greatly concerned patriots in a time of war. Of course the film hasn't aged well: this is carbon-stamped to 1943 as firmly as a movie could possibly be. And yet its insights into how history moves and what role people occupy in it are utterly timeless. As a time capsule and as pure cinema, this is as as essential, enjoyable, and challenging as the movies can get.

The body of work created by the filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (credited equally as writers, directors, and producers, though it's generally understood that Powell was more the director, while Pressburger was more the writer and producer) is arguably the high water mark of all British cinema, and their 1943 collaboration The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is maybe the most essentially, urgently British of the 21 films they made together. It is probably the most epic and ambitious in scale and intention: it's a World War II propaganda film with a real message on its mind other than the usual "We can do it if we stick together!" cheerleading typical of its generic bedfellows, that bases its analysis of what the people of the British isles could and should do to stave off the Nazi threat in a long-form study of military history spanning nearly half of a century. It does this in the body of one immaculately conservative soldier named Major-General Clive Wynne-Candy (Roger Livesey, flawlessly playing a brash youth and a puffed-up old man so distinctly that it's almost difficult to believe that they were both a 37-year-old actor), inspired in his personality and appearance by Colonel Blimp, the star of a satirical comic strip by David Low, but infinitely more expansive in personality; and it does this in the form of what must absolutely be the most excitingly shot British production I can personally name up to that point in history, the moment that Powell's directorial style snapped into focus and provided a visual means of expression that's neither exactly Hollywood nor exactly European. It would not, for my taste, remain the best production released under the banner of the Archers (Powell & Pressburger's independent company, through which they'd make all of their films until 1957), with their post-war efforts A Matter of Life and Death and The Red Shoes eclipsing it in stylistic and structural complexity, and overall excellence, respectively. But it's more radical than they are, inventing out of thin air what they (and the rest of the Archers' output) would thereupon refine and build from.

The movie begins and ends in 1942, where Wynne-Candy is an old and slightly ridiculous ex-Army figure, spending his retirement advising and training the Home Guard. He's introduced as the butt of something halfway between a prank and a political demonstration: the evening afternoon before a war game is meant to start at midnight, brash young lieutenant "Spud" Wilson (James McKechnie) breaks into the Turkish bath where Wynne-Candy and many other old Army outcasts spend their hours, capturing the old man and winning the war game before it begins. This triggers a spirited argument between the two warriors, Wilson insisting that old, traditional conservative men like Wynne-Candy aren't merely out of touch, but acutely dangerous in this new sort of warfare. Chastened and annoyed, the old man finds himself drifting into an extended flashback that rewinds to that same Turkish bath, 41 years prior, when he was just Lieutenant Clive Candy, on leave from the Second Boer War - the flawlessly-executed trick by which a youthful body double substitutes for Livesey in his old age makeup while the camera manages to get slightly too far ahead of the character is the first of many coups du cinéma in the film, seamlessly blurring past and present into one discontinuous chronology that doubles as the first leg in the filmmakers' argument about the way that the past informs the present.

The remainder of the film is largely concerned with three movements, one during the Boer War, one in the days immediately following the First World War, and one in the early years of the Second World War, bringing us finally back to the morning of the day on which we met Candy. In each of these segments, we also see Candy's developing relationship with Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), a German officer with whom Candy duels in 1901, while he's in Berlin on an unofficial mission to defuse an anti-British propaganda effort. And we see as well his encounters with three young women who all look exactly alike, for the good reason that they're all played by Deborah Kerr: Edith Hunter, an idealist who obviously loves Candy but ends up marrying Kretschmar-Schldorff; Barbara Wynne, a pragmatic nurse who marries Candy despite his being much older; and Angela "Johnny" Cannon, who serves as his sharp-tongued assistant and driver as he works with the Home Guard, and ends up helping to bridge the gulf between the honorably conservative Brit and the honorably conservative German while their countries prepare to go to war.

While each sequence is hung on a single driving narrative spine, the overall impression is of a movie that meanders its way through history over the course of two hours and 43 minutes (the film was cut twice before being restored to its full length in 1983; a more thorough clean-up job restoring the vivid colors was completed in 2011), and yet never feels like there's a single sagging moment or unnecessary layover. The script is thoughtful and decisive, crisply marking down character beats for the actors to later flesh in, and presenting symbolic conflicts which feel so personal in their execution that the degree to which this is all a metaphorical satire of British military etiquette hardly gets in the way of what a perfect study of individual lives it is as well. And I will give it this above even A Matter of Life and Death and The Red Shoes and all the rest: it is very possible that this is the best-written of the Archers' film, structurally, psychologically, and thematically. As it cycles back into 1942 and presents its message that men of Candy's era, for all their dignity and experience and intelligence, aren't equipped to fight a war against the systemic evil represented by Nazi Germany, the film generates a fierce passion about its topic mixed with affection, deep and rich and abiding affection, for the characters it's consigning to history. For something with such a serious subject, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp moves forward with enormous generosity and a great deal of fresh, bubbly humor - indeed, it is as much a comedy as otherwise, growing gradually darker towards the end.

The beautiful writing goes hand in hand with exemplary filmmaking technique that draws it out and works it into the visual bones of the movie. It is supremely well made, and not always because it draws attention to itself: one of the most perfect sequences in the movie consists of a camera staring at Walbrook's face as he quietly delivers a deep, probing monologue, pushing into a close-up, and then backing away again. It's so simple as to be virtually anti-cinematic, but it's exactly what the movie needs, both for the integrity of the monologue, and the place it occupies near the very beginning of the 1939 sequence; it promises the seriousness and mournful intimacy that the rest of the film will largely concern itself with, in opposition to the more bright material of the first two-thirds.

Frequently, though, the style is so great precisely because it makes itself felt. There is the comic audacity of the first transition from the Boer War to the First World War, a montage of mounted animal heads representing Candy's somewhat bloodthirsty approach to leisure time until he can get back to business (ending with the nihilistic joke of a Germany army helmet with the descriptive plaque "Hun - Flanders, 1918"); there is the bleak poetry of the second transition from the First World War to the Second, with the Wynne-Candy family album skipping through blank page after blank page following the newspaper clipping of Barbara's death. And there is the richness and moral complexity of the individual images, shot in glowing Technicolor to accentuate the vibrancy of military uniforms and upper class splendor in sharp contrast to default setting of drab earth tones, suggesting throughout (but especially in the Boer War sequence) that the pageantry of the British military and the pride of men like Candy, however handsome and captivating, is also chintzy and surface-level, all glamor without soul. Or consider the way that Powell presents the duel that takes up a huge portion of the first act: the opening preparations are contained within a hollow wide shot of a gymnasium, like a dead cathedral of Continental honor; the actual duel starts during a high-angle crane shot that backs away as Allan Gray's jaunty score kicks in, suggesting a perverse ballet, all part of the theatricality of the lives it presents, before dissolving into a snowstorm.

The visuals are, throughout, sardonic and witty, detached with just enough ghostliness that they feel appropriately out of time and yet anchored by the superbly expressive faces of Livesey and Walbrook that the immediate feeling of the characters' lives is always front and center. The images are satiric while the script is utterly sincere, and the structure is moody and weary while the energy of each scene and each performance is fiery and urgent, communicating with an intensity that could only driven by enthusiastic and greatly concerned patriots in a time of war. Of course the film hasn't aged well: this is carbon-stamped to 1943 as firmly as a movie could possibly be. And yet its insights into how history moves and what role people occupy in it are utterly timeless. As a time capsule and as pure cinema, this is as as essential, enjoyable, and challenging as the movies can get.