To the Max

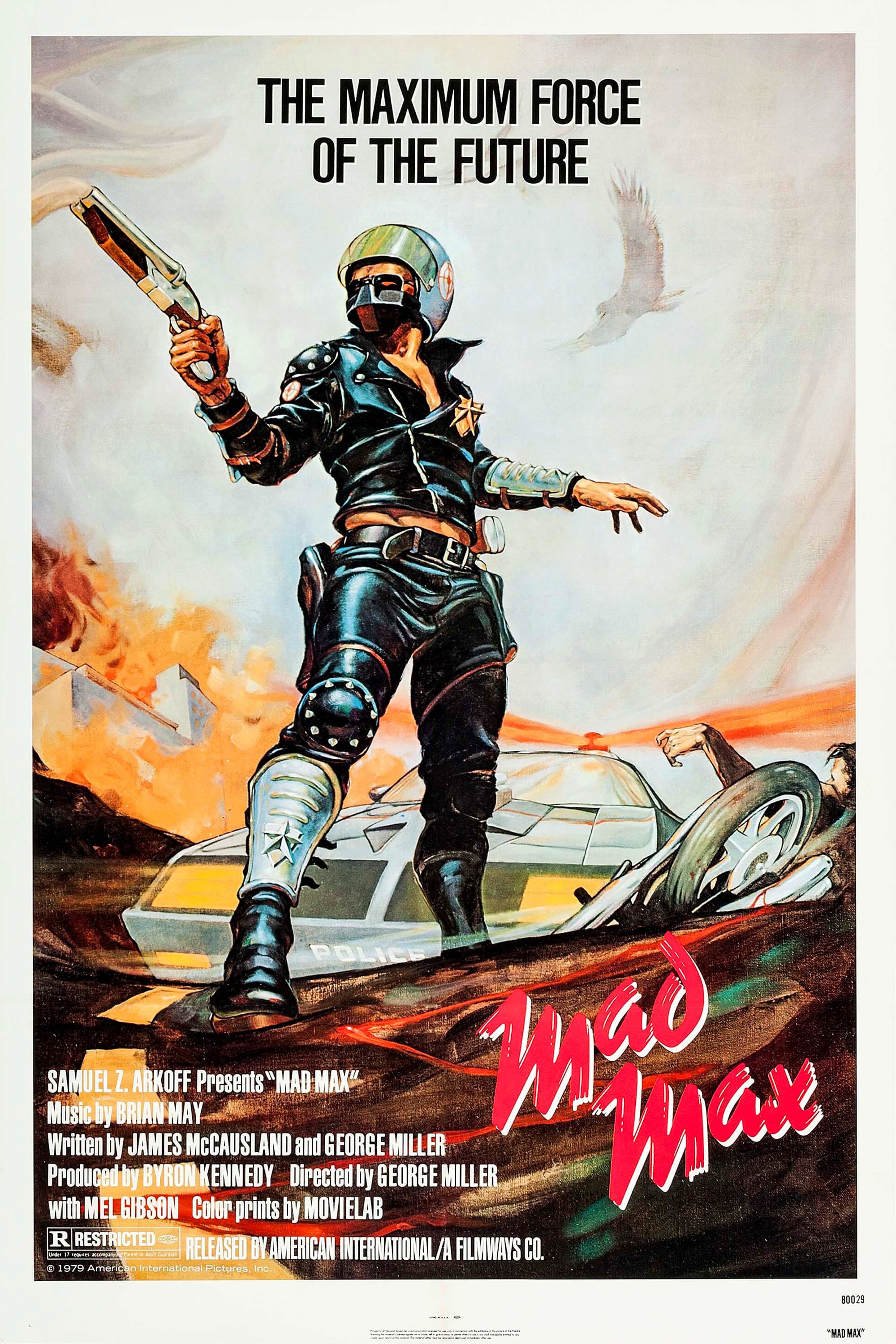

There's no way around it: Mad Max is an astonishingly impressive movie. It was made for pocket change by a bunch of of amateurs: director and co-writer George Miller was a medical doctor, of all things, before he and producer partner Byron Kennedy made the short Violence in the Cinema, Part 1. And that was in 1971, a full eight years before Mad Max found its way into theaters. And despite these grubby origins, the film was an enormous hit, holding the record for the highest ratio of production budget-to-theatrical gross for twenty years, until The Blair Witch Project came along. But the impressive part isn't that Miller and Kennedy and company made a whole fucking lot of money from just a little money. It's that they made a whole fucking lot of movie from just a little money - a movie so ambitious and inventive in its action choreography and cinematography that it effectively re-defined the way that car chases have been filmed for the intervening 36 years. And frankly, only a very small number of its uncountable imitators have managed to improve upon it in any way. This is a masterpiece of stretching resources to the snapping point; it is a film that's obligatory viewing for anybody want wants to make movies themselves. But it's also great purely as entertainment, with its perhaps unjustified narrative shortcuts hardly seeming to be much worth complaining about in the middle of its flawless action sequences.

An opening title card tells us that it's only a few years in the future, but otherwise leaves the backstory unstated. And this is one of the best things that Miller and co-writer James McCausland could possibly have done, since the film-wide lack of specifics doesn't offer any kind of distance between us and the film's world; there's no fantasy involved, as would be true of both of this film's sequels and most of its knock-offs. While Mad Max is usually described as a post-apocalyptic film, that's really not true: it's more of an intra-apocalyptic film, or maybe just ever so slightly pre-apocalyptic. What it depicts is a world with the framework of a functioning society that's starting to get very, very tired and is just about ready to collapse; and the lack of effort the screenwriters put into differentiating that world from our own serves to blur the distinction between Australia in 1979 and the fictional Australia of 1985 or so. The costumes (rather brilliant ones, designed by Clare Griffin), social mores, and car culture are all clearly different from the real world, but they're also close enough that Mad Max describes a culture in freefall that's distressingly easy to extrapolate from the real world. Now, I enjoy the whole genre of post-apocalyptic science fiction about as much as it's possible to do; I don't claim for Mad Max any kind of superiority because it avoids the usual tropes of its genre. I claim for it superiority because it functions as a more visceral cautionary tale than almost anything else in its genre. This isn't a metaphorical, "if we don't change our ways, we could end up in this Bizarro World" type of story. It's "look in the mirror, wouldn't you say we're already kind of there?"

In this apocalypsish world, an energy crisis has led to a general disintegration of the social safety net, and a new culture of lawlessness apparently based in the idea that, what the hell, if there's not enough oil left to save society, we might as well use what little we have left in the most spectacularly pointless ways. And thus the empty roads crisscrossing Australia are dominated by very showy car and motorcyle-based gangs, whose heavily customised vehicles are treated functionally as extensions of the self. With no real sense of morality in the world any longer, these gangs are mean, too. We learn that when we encounter the deranged Nightrider (Vince Gil) and his equally deranged ladyriend (Lulu Punkus) hooting and hollering and speeding around in a car stolen from the Main Patrol Force, the new police force that has been created more so the government can have a gang of its own to meet brutality with brutality, than because there's any real urge to serve and protect the citizenry. Nightrider's joyriding is cut short by one of the MPF's best officers, Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson), who forces the gangbanger into an explosive crash while offering crazed pursuit.

Nightrider's gang is led by a particularly brutal bastard called the Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne), who leads his boys and girls in a mournful celebration of destroying the town where they pick up what little bit remains of Nightrider, and chasing a young couple to the outskirts of town where they're raped and their car is ripped apart. One member of the gang, Johnny the Boy (Tim Burns) is too stoned to leave with his mates, and Max and his partner Goose (Steve Bisley) pick him up, only to find that the town is so terrified that not a single person - not even the couple - is willing to testify against him, and there's no option but to let him escape. This unfortunately means that the gang knows the cops names and faces, and before too long, they've extracted revenge on Goose. Max is ready to quit the force at this point, but his beleagured chief, "Fifi" Macaffe (Roger Ward) talks him into taking a vacation. And in a spectacularly unfortunate coincidence, Max, his wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel), and their little boy Sprog (Brendan Heath) happen to vacation right in the same location that the gang has decamped to. They torment Jessie and Sprog, killing the boy and leaving the woman on death's door; and this, you might say, makes Max go a little bit mad.

What's not clear from a plot synopsis, but seems tremendously significant, is that there's no sense of Max's repeated encounters with the gang having some directed malice behind it. Their assault on the cops following Johnny the Boy's escape from justice is never informed by Nightrider's death; they start to attack Jessie wihtout knowing that she's Max's wife. The sense is less that a demented gang tries to revenge themselves on a cop, than it is of doom stalking the countryside: the Rockatanskys suffer because suffering is the best that you can hope for in a society as utterly rotten as this film's Australia-in-decline. And this is not really the suffering of innocents, either; Max's first action in the film is to casually murder a suspect and destroy costly police property in the process, and and no point from the opening shot of the Hall of Justice with the "U" about the fall off onwards does the film pretend that its cops are heroes just because they're the ones with badges. It's not a place that heroes can exist.

Actually, if the film has one clear-cut problem, it's that the lack of human decency it depicts is so pervasive that the movie itself starts to lose interest in its humans; nobody onscreen has much of a clearly defined personality or inner life, and the y stand out mostly due to how colorful they are. Now, between being an Australian film and taking placed in an exaggerated future, Mad Max has some extremely colorful characters indeed, but these are mostly the villains; Max and Jessie don't really register as anything but clockwork gears who turn because they're made to turn. Mad Max 2 picks up this shortcoming and turns it into one of its signature strengths; but the relative naturalism of Mad Max the first would be better served by having its protagonists exist as something more complex than The Amoral Cop and The Innocent Wife. The mythic scope that the franchise is noted for wasn't quite here yet, and mythic characters don't really fit. Meanwhile, Brian May's score punches up all the domestic scenes that don't quite gel with syrupy romantic motifs, underlining the emotional deficiencies even more.

But here I am, going on about the story and characters of Mad Max like they matter at all. Of course they don't. Unless we agree that the cars are characters at least as important as the humans, and the film makes that argument tremendously well: the scene where the young couple is attacked especially suggests that the vehicles in the film are so much a part of the humans driving them that they can't be distinguished. When the young woman screams in terror, it's placed into the soundtrack against shots of the car being smashes, as though the car itself was bellowing in pain; when Max and Goose find the crime scene, the human victims barely register, while pieces of the car are strewn about the road like bloody limbs after a massacre.

Anyway, the cars and motorcycles are the stars of the show, particularly Max's black-on-black Pursuit Special MFP Interceptor, presented as a combination of sex object and holy relic by Miller and cinematographer David Eggby's admiring camera. These vehicles are at the center of what were, in 1979, the most kinetic driving scenes ever filmed, mounting the camera inside and on the body of vehicles spinning and flipping and sailing through the air, edited by Cliff Hayes and Tony Paterson with a reckless speed that was mostly unknown to the action cinema of the '70s and earlier, but with a zealous attention to continuity that shames their decades of imitators. Mad Max captures frenzied, unpredictable movement with an impact and fluidity that simply did not exist prior to it. It remains tremendously exciting, though history has caught up with it in a way that it hasn't with Mad Max 2>: while I insist, as I said up top, that few films have improved upon Mad Max, a larger number have managed to at least match it. For part of the film's genius was in demonstrating how far you could extend a small budget if you spent it on primarily cars and absolutely insane stunt drivers, and were willing to destroy the former, and like anything which made a huge pile of money, people were very eager to replicate it. The DNA of Mad Max is in every car chase to have been filmed since 1980.

But even if it's not a mind-blowingly fresh as it would have been when it was new, there's precious damn little to grouse about. This is an outstanding action movie, marred only slightly by its limitations as a story and not at all by its low budget. It is a legitimately radical movie, and I honestly suppose that I wouldn't even notice how much room it left for improvement if George Miller himself hadn't gone ahead and improved it two years later.

Reviews in this series

Mad Max (Miller, 1979)

Mad Max 2 AKA The Road Warrior (Miller, 1981)

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (Miller and Ogilvie, 1985)

Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015)

An opening title card tells us that it's only a few years in the future, but otherwise leaves the backstory unstated. And this is one of the best things that Miller and co-writer James McCausland could possibly have done, since the film-wide lack of specifics doesn't offer any kind of distance between us and the film's world; there's no fantasy involved, as would be true of both of this film's sequels and most of its knock-offs. While Mad Max is usually described as a post-apocalyptic film, that's really not true: it's more of an intra-apocalyptic film, or maybe just ever so slightly pre-apocalyptic. What it depicts is a world with the framework of a functioning society that's starting to get very, very tired and is just about ready to collapse; and the lack of effort the screenwriters put into differentiating that world from our own serves to blur the distinction between Australia in 1979 and the fictional Australia of 1985 or so. The costumes (rather brilliant ones, designed by Clare Griffin), social mores, and car culture are all clearly different from the real world, but they're also close enough that Mad Max describes a culture in freefall that's distressingly easy to extrapolate from the real world. Now, I enjoy the whole genre of post-apocalyptic science fiction about as much as it's possible to do; I don't claim for Mad Max any kind of superiority because it avoids the usual tropes of its genre. I claim for it superiority because it functions as a more visceral cautionary tale than almost anything else in its genre. This isn't a metaphorical, "if we don't change our ways, we could end up in this Bizarro World" type of story. It's "look in the mirror, wouldn't you say we're already kind of there?"

In this apocalypsish world, an energy crisis has led to a general disintegration of the social safety net, and a new culture of lawlessness apparently based in the idea that, what the hell, if there's not enough oil left to save society, we might as well use what little we have left in the most spectacularly pointless ways. And thus the empty roads crisscrossing Australia are dominated by very showy car and motorcyle-based gangs, whose heavily customised vehicles are treated functionally as extensions of the self. With no real sense of morality in the world any longer, these gangs are mean, too. We learn that when we encounter the deranged Nightrider (Vince Gil) and his equally deranged ladyriend (Lulu Punkus) hooting and hollering and speeding around in a car stolen from the Main Patrol Force, the new police force that has been created more so the government can have a gang of its own to meet brutality with brutality, than because there's any real urge to serve and protect the citizenry. Nightrider's joyriding is cut short by one of the MPF's best officers, Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson), who forces the gangbanger into an explosive crash while offering crazed pursuit.

Nightrider's gang is led by a particularly brutal bastard called the Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne), who leads his boys and girls in a mournful celebration of destroying the town where they pick up what little bit remains of Nightrider, and chasing a young couple to the outskirts of town where they're raped and their car is ripped apart. One member of the gang, Johnny the Boy (Tim Burns) is too stoned to leave with his mates, and Max and his partner Goose (Steve Bisley) pick him up, only to find that the town is so terrified that not a single person - not even the couple - is willing to testify against him, and there's no option but to let him escape. This unfortunately means that the gang knows the cops names and faces, and before too long, they've extracted revenge on Goose. Max is ready to quit the force at this point, but his beleagured chief, "Fifi" Macaffe (Roger Ward) talks him into taking a vacation. And in a spectacularly unfortunate coincidence, Max, his wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel), and their little boy Sprog (Brendan Heath) happen to vacation right in the same location that the gang has decamped to. They torment Jessie and Sprog, killing the boy and leaving the woman on death's door; and this, you might say, makes Max go a little bit mad.

What's not clear from a plot synopsis, but seems tremendously significant, is that there's no sense of Max's repeated encounters with the gang having some directed malice behind it. Their assault on the cops following Johnny the Boy's escape from justice is never informed by Nightrider's death; they start to attack Jessie wihtout knowing that she's Max's wife. The sense is less that a demented gang tries to revenge themselves on a cop, than it is of doom stalking the countryside: the Rockatanskys suffer because suffering is the best that you can hope for in a society as utterly rotten as this film's Australia-in-decline. And this is not really the suffering of innocents, either; Max's first action in the film is to casually murder a suspect and destroy costly police property in the process, and and no point from the opening shot of the Hall of Justice with the "U" about the fall off onwards does the film pretend that its cops are heroes just because they're the ones with badges. It's not a place that heroes can exist.

Actually, if the film has one clear-cut problem, it's that the lack of human decency it depicts is so pervasive that the movie itself starts to lose interest in its humans; nobody onscreen has much of a clearly defined personality or inner life, and the y stand out mostly due to how colorful they are. Now, between being an Australian film and taking placed in an exaggerated future, Mad Max has some extremely colorful characters indeed, but these are mostly the villains; Max and Jessie don't really register as anything but clockwork gears who turn because they're made to turn. Mad Max 2 picks up this shortcoming and turns it into one of its signature strengths; but the relative naturalism of Mad Max the first would be better served by having its protagonists exist as something more complex than The Amoral Cop and The Innocent Wife. The mythic scope that the franchise is noted for wasn't quite here yet, and mythic characters don't really fit. Meanwhile, Brian May's score punches up all the domestic scenes that don't quite gel with syrupy romantic motifs, underlining the emotional deficiencies even more.

But here I am, going on about the story and characters of Mad Max like they matter at all. Of course they don't. Unless we agree that the cars are characters at least as important as the humans, and the film makes that argument tremendously well: the scene where the young couple is attacked especially suggests that the vehicles in the film are so much a part of the humans driving them that they can't be distinguished. When the young woman screams in terror, it's placed into the soundtrack against shots of the car being smashes, as though the car itself was bellowing in pain; when Max and Goose find the crime scene, the human victims barely register, while pieces of the car are strewn about the road like bloody limbs after a massacre.

Anyway, the cars and motorcycles are the stars of the show, particularly Max's black-on-black Pursuit Special MFP Interceptor, presented as a combination of sex object and holy relic by Miller and cinematographer David Eggby's admiring camera. These vehicles are at the center of what were, in 1979, the most kinetic driving scenes ever filmed, mounting the camera inside and on the body of vehicles spinning and flipping and sailing through the air, edited by Cliff Hayes and Tony Paterson with a reckless speed that was mostly unknown to the action cinema of the '70s and earlier, but with a zealous attention to continuity that shames their decades of imitators. Mad Max captures frenzied, unpredictable movement with an impact and fluidity that simply did not exist prior to it. It remains tremendously exciting, though history has caught up with it in a way that it hasn't with Mad Max 2>: while I insist, as I said up top, that few films have improved upon Mad Max, a larger number have managed to at least match it. For part of the film's genius was in demonstrating how far you could extend a small budget if you spent it on primarily cars and absolutely insane stunt drivers, and were willing to destroy the former, and like anything which made a huge pile of money, people were very eager to replicate it. The DNA of Mad Max is in every car chase to have been filmed since 1980.

But even if it's not a mind-blowingly fresh as it would have been when it was new, there's precious damn little to grouse about. This is an outstanding action movie, marred only slightly by its limitations as a story and not at all by its low budget. It is a legitimately radical movie, and I honestly suppose that I wouldn't even notice how much room it left for improvement if George Miller himself hadn't gone ahead and improved it two years later.

Reviews in this series

Mad Max (Miller, 1979)

Mad Max 2 AKA The Road Warrior (Miller, 1981)

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (Miller and Ogilvie, 1985)

Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015)

Categories: action, oz/kiwi cinema, post-apocalypse, thrillers