Summer of Blood: Silent Horror - In this labyrinth, where night is blind

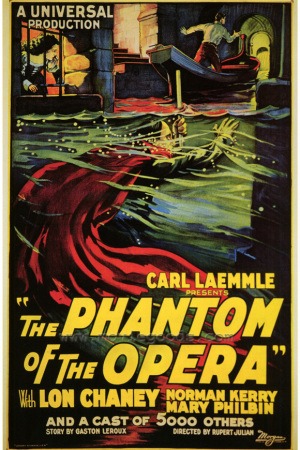

The 1925 version of The Phantom of the Opera is two things. One of these is the best of the small population of pure horror films made in the United States during the silent era. The other is a thorny mess to talk about, so we need to have some history. The short version of the story is all we need, which is that in 1929, Universal shot a large amount of new footage and heavily revised the movie for a 1930 re-release including sound passages, chopping a huge portion of its running time off in the process, and requiring the frame rate bumped up to 24 frames per second, sufficiently faster than the 20 frames per second at which the film was shot that it obvious that it's moving too fast. This 1930 cut has been the basis for almost all subsequent editions of the film, given that it has been preserved (not quite in a complete form) in 35mm, while the 1925 cut now exists only in 16mm home copies that look pretty beaten and battered. Thankfully, the film has been one of the best-served of all silents on high-def video, and there is an edition collecting the 35mm print in both 24 fps and 20 fps, running to 78 and 92 minutes, respectively, as well as the 16mm original at 114 minutes. This review is primarily in response to the 114-minute 1925 cut, though I've also checked in with the quite spectacularly different 92-minute edition of the 1930 cut (enough of the footage is new to that version, and the plot sufficiently different, that I'd argue it should be thought of as a different film entirely). And now the housekeeping is done and we can go on with the actual movie review.

And how glad I am to do that! The Phantom of the Opera, in any cut, is one of the great classic horror masterworks, for reasons that are hardly limited to its most famous element - I refer to the make-up designed by actor Lon Chaney for his performance as the Phantom, among the most iconic images in all of silent cinema, and perhaps the most famous make-up design in the entire history of screen horror. I don't want to diminish anything: Chaney's Phantom design is glorious, and it deserves every molecule of its fame. But there's a great deal of movie above and beyond that design, even beyond that character, and much of it is pretty unreservedly terrific.

Not all of it. It's certainly the case that none of of the other performers in the movie are on the same level as Chaney, which isn't a surprise - I can't name a single one of his films where he isn't giving the most interesting performance. But one particular cast member isn't really any good at all, Mary Philbin, and that's rough, since she's playing the character with the most screen time. Philbin certainly was capable of more than this - she's very good, if hardly one for the ages, in the wonderful 1928 costume drama The Man Who Laughs. Here, though, she's flat and disaffected. It's the exact opposite of the stereotypical problem of silent film acting, which is not so hard to find in 1925 (in fact, not so hard to find in this very film), with wild gesticulations and huge facial expressions: she's subdued to a truly remarkable degree for a silent performance, enough that it slips from "naturalistic acting a decade ahead of schedule" into "leaves no trace of her personality" (she is, to be fair, notably better in the footage shot in 1929). Her scenes with Chaney are easily the best; hard to say if that's the value of having a strong scene partner, or the value of having more interesting situations to play than the dewy, virginal ingénue.

But even with a rocky lead, and a best-in-show performer who doesn't show up until the second quarter of the movie, there's barely a moment of The Phantom of the Opera that doesn't just work at the highest level a genre picture made before its genre had even manifested itself could manage to. This is a seriously impressive horror movie, possibly the only classic of the nascent form from the '20s and '30s that gets at the general feeling of German Expressionism (where cinematic horror as we now think of it was largely invented in the first half of the '20s) without specifically copying the technique of Expressionism. It's a stretch to call it "scary" all these years later - even Chaney's uncanny make-up is more freakish and creepy than scary, partially owing to its cultural ubiquity - but it has a doom-soaked mood of claustrophobic interiors and silhouettes flittering away out of corners, and a staging of a hanged man's shadow that's one of the boldest pieces of lighting you could want from a horror movie.

The focus on decrepitude, night terrors of the unknown, and the crawling sense of dread surrounding this mysterious man who controls Box 5 of the Paris Opera House and has been giving anonymous lessons to the chorine Christine Daaé (Philbin), understudy to the florid prima donna Carlotta (Virginia Pearson - in the most significant narrative change between the two cuts, Pearson plays Carlotta's mother in the 1930 version, which is kind of a nasty trick). A lot of the material that doesn't take place in the catacombs and sewers beneath the Opera, where the Phantom dwells, can run the risk of seeming insubstantial, as generally happened in the other important "straight" adaptation of Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel, Universal's 1943 color epic (which largely gutted the material and transformed it into a solid if frequently weird attempt at an MGM-style melodrama on a budget). Here, though, director Rupert Julian - who had the film taken away and largely reshot by director Edward Sedgwick, only for virtually all of Sedgwick's footage to be discarded after terrible test screenings - does such a good job at layering a constant sense of danger to the beautifully spooky sets, and keeping our attention focused on the Phantom even in the long stretches of the film where he's not present, that even the most unexceptional moments of straightforward character business have a menacing aura that dashes any possibility of this presenting itself as a romantic drama (the approach taken by the famous and infamous Andrew Lloyd Webber musical from 1986, itself adapted into a 2004 movie).

The Phantom himself helps with that, of course: once we finally see him, even before the immaculately-staged reveal of his grotesque face, Chaney makes damn sure that we never stop thinking about the character. There's such stateliness and largeness to Chaney's posture and movement, never shading into self-parodying silent film histrionics: his Phantom has unimaginable, crushing screen presence, whether he's dominating the frame, appearing in a small niche, or standing behind title cards in one of the most stylistically brash cards the film has up its sleeve. Chaney's career is full of tremendously high-impact work and a one-of-a-kind ability to demand the camera's attention, and this is still a good contender for the best performance he ever gave. Then we see the make-up, transforming his features into a repellent distortion of a human face with a death rictus, and there's no contest. This is the role he's known for, and it's the role he absolutely deserves to be known for.

Chaney's terrifying grotesque, domineering and threatening and yet very, very sad; the tense feeling to the camerawork and staging of the sets; the thick and heavy lighting; for all these things, The Phantom of the Opera is an absolutely triumph of sustained mood, one that does, yes, deserve to be called "operatic"; it insists on strong emotional responses to potent cues, and not all of those are what we would now call horror. The longer it goes, the more that Raoul and Christine's romance does become a strong factor in the story and the atmosphere of the film, even if the actors don't manage to sell any kind of real attraction between them. There's a certain kind of desperation to the way the love story plays out, something that feels genuinely fragile and threatened by the sheer scale of the Phantom's menace. It's all oddly weighted, but then, horror had no rules at this point, at least not in America. That leads to freshness and lack of predictable beats; uniquely for a classic horror film, it's really hard to get ahead of the tonal swerves the film takes on the way to its climactic face-offs. This is a landmark movie for any number of reasons, not least of which is that the genre it helped shape so quickly moved away from it that it doesn't feel constrained by that genre; it makes horror a tool rather than an end point, and that results in a very unique kind of energy that makes this one of the most essential horror films made prior to 1968.

Body Count: 3, plus who knows how many innocent opera-goers crushed to death by a falling chandelier.

And how glad I am to do that! The Phantom of the Opera, in any cut, is one of the great classic horror masterworks, for reasons that are hardly limited to its most famous element - I refer to the make-up designed by actor Lon Chaney for his performance as the Phantom, among the most iconic images in all of silent cinema, and perhaps the most famous make-up design in the entire history of screen horror. I don't want to diminish anything: Chaney's Phantom design is glorious, and it deserves every molecule of its fame. But there's a great deal of movie above and beyond that design, even beyond that character, and much of it is pretty unreservedly terrific.

Not all of it. It's certainly the case that none of of the other performers in the movie are on the same level as Chaney, which isn't a surprise - I can't name a single one of his films where he isn't giving the most interesting performance. But one particular cast member isn't really any good at all, Mary Philbin, and that's rough, since she's playing the character with the most screen time. Philbin certainly was capable of more than this - she's very good, if hardly one for the ages, in the wonderful 1928 costume drama The Man Who Laughs. Here, though, she's flat and disaffected. It's the exact opposite of the stereotypical problem of silent film acting, which is not so hard to find in 1925 (in fact, not so hard to find in this very film), with wild gesticulations and huge facial expressions: she's subdued to a truly remarkable degree for a silent performance, enough that it slips from "naturalistic acting a decade ahead of schedule" into "leaves no trace of her personality" (she is, to be fair, notably better in the footage shot in 1929). Her scenes with Chaney are easily the best; hard to say if that's the value of having a strong scene partner, or the value of having more interesting situations to play than the dewy, virginal ingénue.

But even with a rocky lead, and a best-in-show performer who doesn't show up until the second quarter of the movie, there's barely a moment of The Phantom of the Opera that doesn't just work at the highest level a genre picture made before its genre had even manifested itself could manage to. This is a seriously impressive horror movie, possibly the only classic of the nascent form from the '20s and '30s that gets at the general feeling of German Expressionism (where cinematic horror as we now think of it was largely invented in the first half of the '20s) without specifically copying the technique of Expressionism. It's a stretch to call it "scary" all these years later - even Chaney's uncanny make-up is more freakish and creepy than scary, partially owing to its cultural ubiquity - but it has a doom-soaked mood of claustrophobic interiors and silhouettes flittering away out of corners, and a staging of a hanged man's shadow that's one of the boldest pieces of lighting you could want from a horror movie.

The focus on decrepitude, night terrors of the unknown, and the crawling sense of dread surrounding this mysterious man who controls Box 5 of the Paris Opera House and has been giving anonymous lessons to the chorine Christine Daaé (Philbin), understudy to the florid prima donna Carlotta (Virginia Pearson - in the most significant narrative change between the two cuts, Pearson plays Carlotta's mother in the 1930 version, which is kind of a nasty trick). A lot of the material that doesn't take place in the catacombs and sewers beneath the Opera, where the Phantom dwells, can run the risk of seeming insubstantial, as generally happened in the other important "straight" adaptation of Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel, Universal's 1943 color epic (which largely gutted the material and transformed it into a solid if frequently weird attempt at an MGM-style melodrama on a budget). Here, though, director Rupert Julian - who had the film taken away and largely reshot by director Edward Sedgwick, only for virtually all of Sedgwick's footage to be discarded after terrible test screenings - does such a good job at layering a constant sense of danger to the beautifully spooky sets, and keeping our attention focused on the Phantom even in the long stretches of the film where he's not present, that even the most unexceptional moments of straightforward character business have a menacing aura that dashes any possibility of this presenting itself as a romantic drama (the approach taken by the famous and infamous Andrew Lloyd Webber musical from 1986, itself adapted into a 2004 movie).

The Phantom himself helps with that, of course: once we finally see him, even before the immaculately-staged reveal of his grotesque face, Chaney makes damn sure that we never stop thinking about the character. There's such stateliness and largeness to Chaney's posture and movement, never shading into self-parodying silent film histrionics: his Phantom has unimaginable, crushing screen presence, whether he's dominating the frame, appearing in a small niche, or standing behind title cards in one of the most stylistically brash cards the film has up its sleeve. Chaney's career is full of tremendously high-impact work and a one-of-a-kind ability to demand the camera's attention, and this is still a good contender for the best performance he ever gave. Then we see the make-up, transforming his features into a repellent distortion of a human face with a death rictus, and there's no contest. This is the role he's known for, and it's the role he absolutely deserves to be known for.

Chaney's terrifying grotesque, domineering and threatening and yet very, very sad; the tense feeling to the camerawork and staging of the sets; the thick and heavy lighting; for all these things, The Phantom of the Opera is an absolutely triumph of sustained mood, one that does, yes, deserve to be called "operatic"; it insists on strong emotional responses to potent cues, and not all of those are what we would now call horror. The longer it goes, the more that Raoul and Christine's romance does become a strong factor in the story and the atmosphere of the film, even if the actors don't manage to sell any kind of real attraction between them. There's a certain kind of desperation to the way the love story plays out, something that feels genuinely fragile and threatened by the sheer scale of the Phantom's menace. It's all oddly weighted, but then, horror had no rules at this point, at least not in America. That leads to freshness and lack of predictable beats; uniquely for a classic horror film, it's really hard to get ahead of the tonal swerves the film takes on the way to its climactic face-offs. This is a landmark movie for any number of reasons, not least of which is that the genre it helped shape so quickly moved away from it that it doesn't feel constrained by that genre; it makes horror a tool rather than an end point, and that results in a very unique kind of energy that makes this one of the most essential horror films made prior to 1968.

Body Count: 3, plus who knows how many innocent opera-goers crushed to death by a falling chandelier.

Categories: horror, summer of blood, universal horror, worthy adaptations