Blockbuster History: Pairs of funny women

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the high concept behind Hot Pursuit is counter-programming, of course, but it's also the latest in Hollywood's cynical attempt to figure what these "woman" people might do if we made them the lead of a picture. It is unsuccessful in the extreme, but not all such efforts have been.

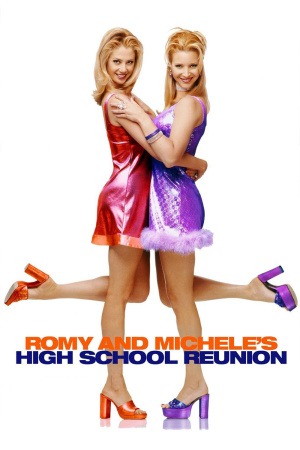

There's, like, a whole movie attached to Romy and Michele's High School Reunion, but I would be remiss in not pointing out to start that, good or bad as a complete work of cinema, this 1997 release is one of the most dauntingly '90s-soaked movies I can imagine. The cast, the design, the soundtrack, the explicitly post-Clueless tone: it's possible to exactly date its theatrical release just based on the twin presences of Mira Sorvino and Camryn Manheim. Or the fact that Mira Sorvino is the top-billed cast member, for that matter.

Sorvino is Romy White; Michele is Michele Weinberger, played by Lisa Kudrow in the first important starring role of her career, following the explosion of Friends on TV. They're a pair of absolute airheads living and doing very little in Los Angeles, perfectly content in their little bubble until Romy bumps into their old high school classmate, the spectacularly bitter Heather Mooney (Janeane Garofalo), and is reminded that their ten-year high school reunion is happening soon. Since she bumped into Heather at her boring job at a Jaguar dealership, handing Heather the keys to a brand new sportscar, she's also been reminded that she and Michele have utterly unspectacular lives, the two best friends decide to throw themselves into the task of reinventing their lives. Failing that, they decide to simply lie about themselves when they head back to Tucson and all the shallow pretty people that once made their lives hell.

It's neither the most original nor sophisticated concept out there, and the film much prefers to wade around in the shallow end of stereotypes: besides the protagonists, archetypal dumb Angelino blondes, it has its share of dopey jocks, socially incompetent nerds, sullen goth types, and prim bitchy queen bees. The usual high school movie stock company, presented in a series of flashbacks threaded throughout the unusually long first act. And while the scenes at the actual reunion allow most of those characters to grow (largely into different, semi-related stereotypes), there's not a subversive bone in the film's body. All of which I throw out largely to preemptively defend myself against claiming that, for all its lack of complication or challenge, Romy and Michele has the basic decency to be a genuinely good comedy, using its clichés for the exact purpose that clichés serve best: to quickly let the audience grasp the situations and characters, so that the business of doing interesting and hopefully things with and to those characters can commence. Writer Robin Schiff, adapting her own play, is terrific at permitting her protagonists to drive the film rather than place them into a film she's already worked out; she also understands them so well that even as they are virtually clones, there's not a point in the movie where it feels like Romy and Michele could be swapped out for each other. It's a terrific reminder that even if a storyteller is dealing with the stupidest bullshit possible, it's still their job to treat that bullshit thoughtfully and honestly, to commit to it and its internal logic. It's a freewheeling script, full of plenty of random asides and absurd cutaways, but it's disciplined. I admire that, profoundly.

More to the point, it gives Romy and Michele a sturdy foundation for director David Mirkin, making his first feature after a career television (where he was and is a Simpsons producer, which certainly must have helped with all the non sequitur humor in the script), to create a brightly paced farce, and for the cast to dig into some awfully silly nonsense without having to worry about embarrassing themselves. It is not the case that the cast is uniformly great: long before it was obvious that Kudrow was the most talented member of the Friends ensemble (sorry, Aniston fans; when you can show me Jen's equivalent to The Comeback, we'll talk), she acted rings around Sorvino here, even though playing an only minor variation on Friends' Phoebe (idiot with a sweet heart and a conniving streak) didn't give her much of a shot to show off. And Garofalo, in the era of her peak powers, stomps on them both, though she's playing just as much to type as Kudrow (the only other person in the movie with a big enough part to feel like she's competing for attention is Julia Campbell as the main snobby antagonist; it's the most stock part of all, and she plays it that way, largely because the movie requires it.

Still, there aren't any really bad performances, and even accounting for the mismatch between Kudrow and Sorvino, the actors both contribute an impressive sense of comfort with each other, borrowing each others' mannerisms and ways of speaking in the fashion of people who've spent so much time with each other that they don't even notice that they're doing it. For all its mocking treatment of the characters - it's not really possible to overstate how much Romy and Michele is founded in the idea that Romy and Michele are clueless - the film is at least as good at depicting the snug rhythm of a good friendship with admirable affection and heart (its overall tone is kind of familial - the old "I can make fun of these people but don't you dare" bit).

Mirkin shepherds this onto the screen with a light touch and some small measure of style, even; the frequent transitions in and out of flashbacks involve visual echoes throughout the first half of the movie or so, smart craftsmanship that serves the needs of the comedy without getting in the way. It's not fussy; the film's driven by its sarcastic attitude that flits quickly from moment to moment and line to line, and overburdening that with interesting visuals would be more than the script could bear. But for what needs to happen, it works perfectly. I would try to avoid going too far in my praise for the film: if nothing else, it's so anchored to an era-specific sense of irony and even more era-specific cultural references, and I concede that I happen to have been close to the perfect age in 1997 to encounter the film for the first time in 2015 with the right mixture of detachment and nostalgia to end up right on its wavelength. Even without that, though, the film has enough goodness in it - an enjoyable push-pull relationship to its leads, and swiftness in its pacing that keeps it from ever bogging down - to work as a light comedy that picks at questions of pride and failed life goals without doubling down so hard that it ever becomes particularly weighty.

There's, like, a whole movie attached to Romy and Michele's High School Reunion, but I would be remiss in not pointing out to start that, good or bad as a complete work of cinema, this 1997 release is one of the most dauntingly '90s-soaked movies I can imagine. The cast, the design, the soundtrack, the explicitly post-Clueless tone: it's possible to exactly date its theatrical release just based on the twin presences of Mira Sorvino and Camryn Manheim. Or the fact that Mira Sorvino is the top-billed cast member, for that matter.

Sorvino is Romy White; Michele is Michele Weinberger, played by Lisa Kudrow in the first important starring role of her career, following the explosion of Friends on TV. They're a pair of absolute airheads living and doing very little in Los Angeles, perfectly content in their little bubble until Romy bumps into their old high school classmate, the spectacularly bitter Heather Mooney (Janeane Garofalo), and is reminded that their ten-year high school reunion is happening soon. Since she bumped into Heather at her boring job at a Jaguar dealership, handing Heather the keys to a brand new sportscar, she's also been reminded that she and Michele have utterly unspectacular lives, the two best friends decide to throw themselves into the task of reinventing their lives. Failing that, they decide to simply lie about themselves when they head back to Tucson and all the shallow pretty people that once made their lives hell.

It's neither the most original nor sophisticated concept out there, and the film much prefers to wade around in the shallow end of stereotypes: besides the protagonists, archetypal dumb Angelino blondes, it has its share of dopey jocks, socially incompetent nerds, sullen goth types, and prim bitchy queen bees. The usual high school movie stock company, presented in a series of flashbacks threaded throughout the unusually long first act. And while the scenes at the actual reunion allow most of those characters to grow (largely into different, semi-related stereotypes), there's not a subversive bone in the film's body. All of which I throw out largely to preemptively defend myself against claiming that, for all its lack of complication or challenge, Romy and Michele has the basic decency to be a genuinely good comedy, using its clichés for the exact purpose that clichés serve best: to quickly let the audience grasp the situations and characters, so that the business of doing interesting and hopefully things with and to those characters can commence. Writer Robin Schiff, adapting her own play, is terrific at permitting her protagonists to drive the film rather than place them into a film she's already worked out; she also understands them so well that even as they are virtually clones, there's not a point in the movie where it feels like Romy and Michele could be swapped out for each other. It's a terrific reminder that even if a storyteller is dealing with the stupidest bullshit possible, it's still their job to treat that bullshit thoughtfully and honestly, to commit to it and its internal logic. It's a freewheeling script, full of plenty of random asides and absurd cutaways, but it's disciplined. I admire that, profoundly.

More to the point, it gives Romy and Michele a sturdy foundation for director David Mirkin, making his first feature after a career television (where he was and is a Simpsons producer, which certainly must have helped with all the non sequitur humor in the script), to create a brightly paced farce, and for the cast to dig into some awfully silly nonsense without having to worry about embarrassing themselves. It is not the case that the cast is uniformly great: long before it was obvious that Kudrow was the most talented member of the Friends ensemble (sorry, Aniston fans; when you can show me Jen's equivalent to The Comeback, we'll talk), she acted rings around Sorvino here, even though playing an only minor variation on Friends' Phoebe (idiot with a sweet heart and a conniving streak) didn't give her much of a shot to show off. And Garofalo, in the era of her peak powers, stomps on them both, though she's playing just as much to type as Kudrow (the only other person in the movie with a big enough part to feel like she's competing for attention is Julia Campbell as the main snobby antagonist; it's the most stock part of all, and she plays it that way, largely because the movie requires it.

Still, there aren't any really bad performances, and even accounting for the mismatch between Kudrow and Sorvino, the actors both contribute an impressive sense of comfort with each other, borrowing each others' mannerisms and ways of speaking in the fashion of people who've spent so much time with each other that they don't even notice that they're doing it. For all its mocking treatment of the characters - it's not really possible to overstate how much Romy and Michele is founded in the idea that Romy and Michele are clueless - the film is at least as good at depicting the snug rhythm of a good friendship with admirable affection and heart (its overall tone is kind of familial - the old "I can make fun of these people but don't you dare" bit).

Mirkin shepherds this onto the screen with a light touch and some small measure of style, even; the frequent transitions in and out of flashbacks involve visual echoes throughout the first half of the movie or so, smart craftsmanship that serves the needs of the comedy without getting in the way. It's not fussy; the film's driven by its sarcastic attitude that flits quickly from moment to moment and line to line, and overburdening that with interesting visuals would be more than the script could bear. But for what needs to happen, it works perfectly. I would try to avoid going too far in my praise for the film: if nothing else, it's so anchored to an era-specific sense of irony and even more era-specific cultural references, and I concede that I happen to have been close to the perfect age in 1997 to encounter the film for the first time in 2015 with the right mixture of detachment and nostalgia to end up right on its wavelength. Even without that, though, the film has enough goodness in it - an enjoyable push-pull relationship to its leads, and swiftness in its pacing that keeps it from ever bogging down - to work as a light comedy that picks at questions of pride and failed life goals without doubling down so hard that it ever becomes particularly weighty.

Categories: blockbuster history, comedies, farce