Bully pulpit

All due respect to the recent spate of high-profile horror movies to be critically fêted on account of being actually good, but one of the things that The Babadook and It Follows have in common is that they're both immensely well-made versions of something that's already been done. Now, quite unexpectedly, we have the opposite, in the form of Unfriended (which premiered under the name Cybernatural, and that simply doesn't do for something made later than 1997, and not a soft-core cable porno). Legitimately, it's as formally radical as any American film in years, and that despite being a genre picture; despite sounding like a slightly tarted-up first-person camera movie, and especially like 2013's The Den, it's only superficially the same thing. It is the rarest of the rare: it has created a totally new set of storytelling tools, laying out the rules for a new kind movie that, a year or two from now, I am hopeful might be used in a really aggressive, challenging way, the first great work of quintessentially Millennial art.

The problem is that Unfriended, aside from inventing a new language, is shit.

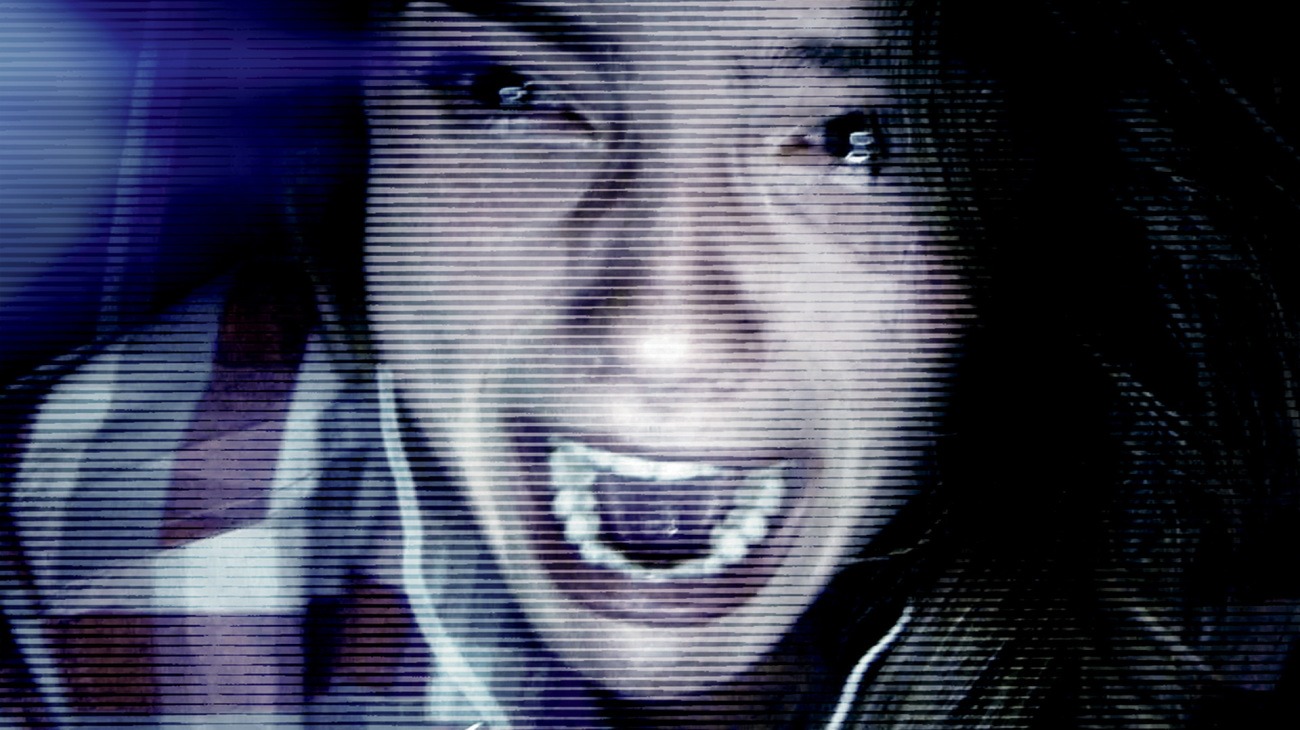

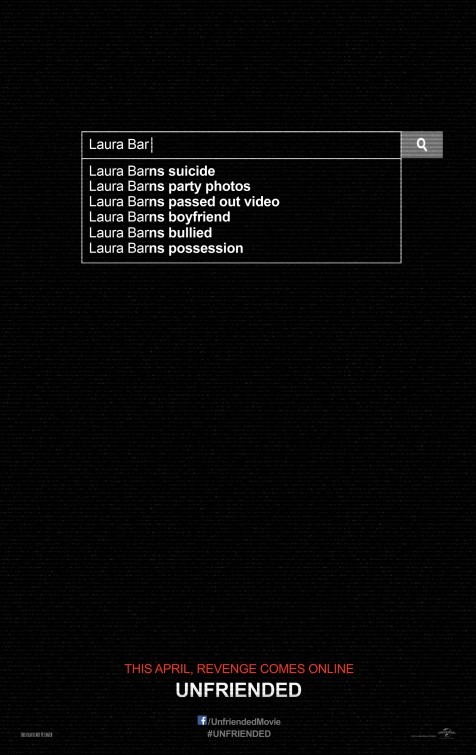

But I would like to accentuate the positive for starters, since the things that are bad about Unfriended are common to a great many poor horror films, and the things that are good are almost totally unique. The notion is that high school student Blaire Lily (Shelley Hennig) and her boyfriend Mitch Roussel (Moses Jacob Storm) are all ready to have a fun night of sexually taunting each other on Skype, when their friends Jess Felton (Renee Olstead), Adam Sewell (Will Peltz), and Ken "Kennington" Smith (Jacob Wysocki) jump into the fray, somehow, using computer trickery best described as "the screenwriter wanted it". The five of them banter a bit, getting increasingly annoyed at the sixth individual apparently listening in on their call, trying to figure it out, accusing snotty frenemy Val Rommel (Courtney Halverson) of being the hacker and dragging her into their chat, and only eventually figuring out that what might be going, and since this is a horror film, "might be" = "surely is", is that the dead Laura Barns (Heather Sossaman), who committed suicide one year ago tonight, could be haunting everybody she thinks is responsible for bullying her into killing herself following a humiliating YouTube video that showed her drunk and covered in her own filth. Which does in fact mean that she wants revenge on, basically, the whole school, and I imagine that's to be the sequel hook.

Now, there's nothing special about any of that, except that the whole film is shown as a shot of of Blaire's MacBook desktop. And here's where we must be very specific about what we mean: it's not the footage being shown on Skype, a gimmick that dates at least back to the segment "The Sick Thing That Happened to Emily When She Was Younger" from 2012's V/H/S, and it's not the Skype window with instant messages popping up in front of it, as in The Den. It is, literally, the whole of the desktop, with .jpgs and folders visible around the edges of windows that include Chrome, Skype, Apple iMessage, and Spotify, at least. Which is one important thing already: Unfriended uses name brand programs, and that adds immeasurably to its sense of realism compared to movies that have people using InstaChat and searching on Snoople, or whatever drippy pseudonyms the copyright-dodging screenwriter came up with that week.

That's lovely, but the really exciting thing, what makes Unfriended totally new in my experience, is that it's showing us the unfiltered version of what happens on Blaire's computer: we see the entire record of her life online, with all the various traces of abandoned thoughts on the titles of browser tabs and in her Facebook history, the programs she had open when she started to flirt with Mitch. And other than the appearance of the mouse arrow as she selects what she's focusing on, there's nothing in the movie to guide our eye; we simply get to decide whether it's the actual video of Laura's death we want to stare at, or the sidebar of "also suggested" videos, we can spy on her song playlist. What Unfriended has done is lay out the rules for how a movie can depict and move through that digital space; it has given the foundation to a filmmaker who wants to go for broke and really experiment by making all of that unfocused side detail where the actual storytelling happens, using scraps and errata that we can look at but don't have to, leaving swaths of important character detail spread out across a screen such that we can't see everything and have to prioritise what to look at. Unfriended even starts to be aware of that possibility, as it leaves sometimes up to six different video chat screens playing at once, and not always having the most prominent ones include the most interesting information.

That being said, while I have no doubt that a truly radical experimental narrative shall be made using this aesthetic, Unfriended is absolutely not it - all that wonderful space it leaves itself for squirreling away important bits of information in little side details is wasted on in-jokes and generic filler, the functional equivalent of "lorem ipsum" paragraphs. And it can't even be bothered to keep continuity straight: the action is clarified to take place in April, and we see certain Facebook well-wishes that are time-stamped to "January" and "X hours ago" at different points, all in story that takes place in real time over 80 minutes. There's also a countdown that skips from 10 to 5. So much for hiding interesting details in plain sight.

The plot, meanwhile, is generic "revenge against the obnoxious teenagers" boilerplate, interesting solely in that the exposition is given out of order and throughout the entire movie, so it all seems a bit more mysterious than in your average slasher, where we understand the point of the revenge more or less from the beginning. But a slasher is exactly what it boils down to, including both the regressive sexual morality (we discover that one character isn't a virgin at exactly the point that the movie begins to turn against that character) and the one-word personality types: the Druggie, the Horndog, the Bitch, the Geek, the Bitch (2), and the Hypocrite. Screenwriter Nelson Greaves's desire to structure this as a mystery and give the film a sucker punch twist ending turn into a tawdry trick, thereby trivialising the only thing about the story that had any prayer of being interesting: the film thinks that it's telling a complex tale of how bullying works in the age of social media, pointing out that bullies can be bullied themselves, and that dogpiling is a horrible fucking thing to do to people, no matter how distasteful they are. But its reliance on cheap horror tropes and shabby shocks devalues that theme significantly.

It's painfully unscary - I suspect that watching it on a television or, preferably, a computer might give it more oomph than seeing it in a movie theater possibly could - and includes one of the most contrived death scenes in recent horror cinema (assuming one would, for whatever reason, keep a blender in their bedroom, would it even so be possible to commit suicide with it?). And the filmmakers' enthusiasm for the Kids and their Ways leads ultimately to a deeply misguided climax built around a high-stakes game of "Never Have I Ever" that is bafflingly silly. So, let's be clear, I emphatically do not recommend this film. It's like someone invented the English language by writing The Da Vinci Code. But I do look forward to recommending its most successful knock-offs a few years down the road.

The problem is that Unfriended, aside from inventing a new language, is shit.

But I would like to accentuate the positive for starters, since the things that are bad about Unfriended are common to a great many poor horror films, and the things that are good are almost totally unique. The notion is that high school student Blaire Lily (Shelley Hennig) and her boyfriend Mitch Roussel (Moses Jacob Storm) are all ready to have a fun night of sexually taunting each other on Skype, when their friends Jess Felton (Renee Olstead), Adam Sewell (Will Peltz), and Ken "Kennington" Smith (Jacob Wysocki) jump into the fray, somehow, using computer trickery best described as "the screenwriter wanted it". The five of them banter a bit, getting increasingly annoyed at the sixth individual apparently listening in on their call, trying to figure it out, accusing snotty frenemy Val Rommel (Courtney Halverson) of being the hacker and dragging her into their chat, and only eventually figuring out that what might be going, and since this is a horror film, "might be" = "surely is", is that the dead Laura Barns (Heather Sossaman), who committed suicide one year ago tonight, could be haunting everybody she thinks is responsible for bullying her into killing herself following a humiliating YouTube video that showed her drunk and covered in her own filth. Which does in fact mean that she wants revenge on, basically, the whole school, and I imagine that's to be the sequel hook.

Now, there's nothing special about any of that, except that the whole film is shown as a shot of of Blaire's MacBook desktop. And here's where we must be very specific about what we mean: it's not the footage being shown on Skype, a gimmick that dates at least back to the segment "The Sick Thing That Happened to Emily When She Was Younger" from 2012's V/H/S, and it's not the Skype window with instant messages popping up in front of it, as in The Den. It is, literally, the whole of the desktop, with .jpgs and folders visible around the edges of windows that include Chrome, Skype, Apple iMessage, and Spotify, at least. Which is one important thing already: Unfriended uses name brand programs, and that adds immeasurably to its sense of realism compared to movies that have people using InstaChat and searching on Snoople, or whatever drippy pseudonyms the copyright-dodging screenwriter came up with that week.

That's lovely, but the really exciting thing, what makes Unfriended totally new in my experience, is that it's showing us the unfiltered version of what happens on Blaire's computer: we see the entire record of her life online, with all the various traces of abandoned thoughts on the titles of browser tabs and in her Facebook history, the programs she had open when she started to flirt with Mitch. And other than the appearance of the mouse arrow as she selects what she's focusing on, there's nothing in the movie to guide our eye; we simply get to decide whether it's the actual video of Laura's death we want to stare at, or the sidebar of "also suggested" videos, we can spy on her song playlist. What Unfriended has done is lay out the rules for how a movie can depict and move through that digital space; it has given the foundation to a filmmaker who wants to go for broke and really experiment by making all of that unfocused side detail where the actual storytelling happens, using scraps and errata that we can look at but don't have to, leaving swaths of important character detail spread out across a screen such that we can't see everything and have to prioritise what to look at. Unfriended even starts to be aware of that possibility, as it leaves sometimes up to six different video chat screens playing at once, and not always having the most prominent ones include the most interesting information.

That being said, while I have no doubt that a truly radical experimental narrative shall be made using this aesthetic, Unfriended is absolutely not it - all that wonderful space it leaves itself for squirreling away important bits of information in little side details is wasted on in-jokes and generic filler, the functional equivalent of "lorem ipsum" paragraphs. And it can't even be bothered to keep continuity straight: the action is clarified to take place in April, and we see certain Facebook well-wishes that are time-stamped to "January" and "X hours ago" at different points, all in story that takes place in real time over 80 minutes. There's also a countdown that skips from 10 to 5. So much for hiding interesting details in plain sight.

The plot, meanwhile, is generic "revenge against the obnoxious teenagers" boilerplate, interesting solely in that the exposition is given out of order and throughout the entire movie, so it all seems a bit more mysterious than in your average slasher, where we understand the point of the revenge more or less from the beginning. But a slasher is exactly what it boils down to, including both the regressive sexual morality (we discover that one character isn't a virgin at exactly the point that the movie begins to turn against that character) and the one-word personality types: the Druggie, the Horndog, the Bitch, the Geek, the Bitch (2), and the Hypocrite. Screenwriter Nelson Greaves's desire to structure this as a mystery and give the film a sucker punch twist ending turn into a tawdry trick, thereby trivialising the only thing about the story that had any prayer of being interesting: the film thinks that it's telling a complex tale of how bullying works in the age of social media, pointing out that bullies can be bullied themselves, and that dogpiling is a horrible fucking thing to do to people, no matter how distasteful they are. But its reliance on cheap horror tropes and shabby shocks devalues that theme significantly.

It's painfully unscary - I suspect that watching it on a television or, preferably, a computer might give it more oomph than seeing it in a movie theater possibly could - and includes one of the most contrived death scenes in recent horror cinema (assuming one would, for whatever reason, keep a blender in their bedroom, would it even so be possible to commit suicide with it?). And the filmmakers' enthusiasm for the Kids and their Ways leads ultimately to a deeply misguided climax built around a high-stakes game of "Never Have I Ever" that is bafflingly silly. So, let's be clear, I emphatically do not recommend this film. It's like someone invented the English language by writing The Da Vinci Code. But I do look forward to recommending its most successful knock-offs a few years down the road.