Who can take a sunrise, and sprinkle it with blood?

A review requested by Michael R, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

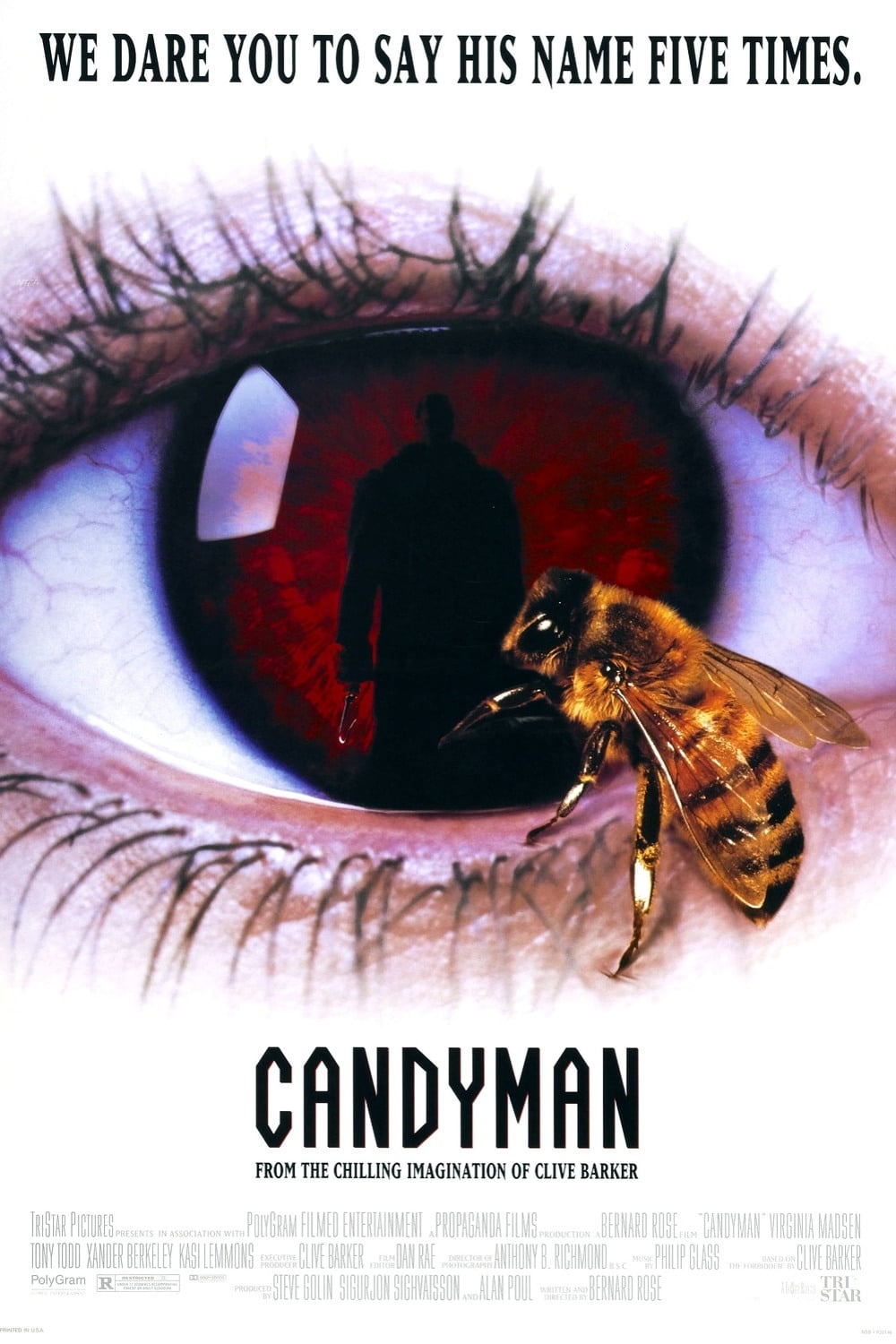

Let's not dick around here: Candyman is the finest American horror film of the 1990s. Now, admittedly, those who've been hanging around this blog for all that long are aware that for me to make this claim of superiority is about on par with declaring something "the finest swift kick to the nutsack". But I promise that my enthusiasm has much more do with the quantity of things that Candyman gets right than with the general poverty of its competition.

Adapted by writer-director Bernard Rose from Clive Barker's short story "The Forbidden", Candyman centers upon a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen), researching urban legends for her thesis. One of these legends involves a ghostly killer with a hook for a hand, who appears when you say his name, "Candyman", in front of a mirror five times. A cleaning woman happens to overhear Helen transcribing her notes, and talks about the story in a much more matter-of-fact way than the giggling undergrads swapping campfire tales, mentioning among other particularly concrete details that the Candyman is known to haunt the Cabrini-Green housing project on the city's north side. And so Helen and her research partner Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons) head up to the dangerous gang hub to poke around and find what they can find.

That's barely even the set-up for the movie, but it's already enough to clue us in to exactly what makes Candyman such an unusual achievement. In changing the setting from Barker's native England to Chicago and Cabrini-Green, Rose fundamentally re-shapes the territory that the story can occupy. The no-longer-extant Cabrini-Green, my younger readers may not know and my non-American readers would have no reason to be aware, was arguably the most notoriously dangerous and mismanaged housing project in the United States, a shorthand for urban blight, the inability of civic governments to do right by their communities, and the abysmal failure of white America to care about the fate of black America, and to generally assume that African-Americans were, when left to their own devices, prone towards violent thuggery. Setting a story in Cabrini-Green, in 1992 (three years before the beginning of the 16 year demolition project that has sought to reclaim the area for upper-middle class yuppies*), could not help but force that story to refocus itself as a statement on race in America. I would go so far as to say that's the primary reason why somebody would choose that location.

And lo! quite a parable about the U.S. race problem Candyman proves to be, though it has the luxury, being a horror film, of never having to come right out and say what's going on. But subtle it ain't. There is, for one thing, the backstory of the Candyman himself (played by Tony Todd when we eventually see him, around halfway through the movie): the son of a slave, tortured and burned to death for the crime of having a consensual sexual relation with a white woman in the 1890s. He is the angry patron spirit of every African-American male who was unjustly punished for the crime, essentially, of not being white. And what happens over the course of the plot? A white chick bumbles around in a place where she doesn't fit in, does what seems to be the right thing (she ends up uncovering the identity of a local gangleader who has been using the Candyman legend as a fear tactic, all Scooby-Doo like), but her actions - born in the pretty explicit conception of Cabrini-Green as a whole breeding ground of Others that she can use as intellectual fodder without having to deal too much with the actual material of their lives - serve only to make things worse, since her actions are what end up rousing the Candyman. As he tells her, point blank, if she wasn't so hellbent on taking away the power of his legend by running it through academia, he wouldn't have to put in such extreme measures to keep that legend fresh and ever more terrifying.

It is, in microcosm, the great American tale of over-educated white people with no fucking clue messing around with the lives of minorities like a kid with a lab kit, to disastrous results. It is, in fact, pretty obvious once you start looking for it. But the film takes the privilege of genre and never bothers to state its themes in the way of an actual message movie (which is perhaps why it gets to have such a cynical message that so signally refuses to lets its white characters off the hook. Although, the film is rather notable for how few important white characters there are: just Madsen herself, and Xander Berkeley as her husband. Her shady husband, but of course we already knew that from "Xander Berkeley"). And if the only thing you wanted Candyman to be was a horror movie, there's still plenty of fantastic work being done purely at the level of genre. The roots in Barker are clear even without the film's portrayal of the Candyman, with its distinct debt to Pinhead from Hellraiser: it's a film about the terrifying power of ideas, as much as the terrifying power of being split in two by a ghost with a hook for a hand. As one of the first films to pivot around the phrase "urban legend", then at its very trendiest, it's little surprise that Candyman should turn out to be about the dangerous power of storytelling, and the woe that befalls those who don't sufficiently respect that power. We can broaden that a bit: it's a film about failing to appreciate the role of culture, history, and knowledge: Helen ends up on the Candyman's bad side because she treats him as a lark, as opposed to the Cabrini-Green locals, who have a grave respect mingled with their hatred for him.

It's also, to be fair, a horror film that works at a gut level as much as an intellectual one, which is after all where horror needs to succeed. Much of that can be credited to Todd, a great character actor with an outstanding ability to seem menacing while being still and richly erudite. Much of it can be credited to the sound mix, which puts Todd's booming voice on a different level than the rest of the sound in the film, feeling like it's entering your head through something other than your ears. A whole shitload of it can be credited to Philip Glass, whose score is one of the best a horror film has enjoyed since the dawn of the 1980s: the droning repetition for which he's famous works perfectly in context, coming off as a dolorous chant as it throbs and throbs its way down into your bones. Glass is such a natural for horror that I have no clue why there are so few horror movies in his career; it worked magnificently in this case.

Arguably, the single element of Candyman that works best, though, is its sense of place. The location photography here is abnormally good: in the 23 years since, I can't name a half-dozen films to have taken advantage of Chicago anywhere near as well, and perhaps only one - The Dark Knight - to have topped it. The film opens with a series of aerial shots, with Glass's music brooding beneath, that start off by rendering Chicago as a flat, indecipherable map of lines and squares that only resemble buildings if you deeply want them to, putting us at into a disconcerting mood right from the beginning (is this an American city? An alien planet? Why not both!). The footage shot in Cabrini-Green, meanwhile, takes superb advantage of the run-down bleakness of that place, portraying it as a victim of human mismanagement that has been turned into something totally inhumane, an unnervingly authentic hellhole where it feels entirely plausible that such forgotten, hidden legends as the one the film builds itself on could survive and thrive.

Given such an extraordinarily suggestive central location, the film gets to do a lot with mood and implication, letting story elements bubble up without having to spell them out. I am particularly fond of the production design in the Candyman shrine - which I presume to have been shot on a studio set back in California - where the full range of Candyman lore is indicated through the paintings on the wall and the plates of chocolates with razor blades in them, but never explained. It suggests a deep background to this story, one that we and Helen never begin to tap or understand, and that lack of understanding is the driving force of everything bad that happens. Candyman is, essentially, a horror film about the danger of confident ignorance, whether that comes in the form of blithely accepting your husband's obvious lies about the undergrad he's fucking, or in the form of trying to reason with a vengeful ghost, or in the form of thinking you can know more about a lifestyle than the people who live it every day. It's brainy, it's atmospheric, and it's spooky as hell, and for all these reasons and more, Candyman is one of the essential works of modern English-language horror.

Reviews in this series

Candyman (Rose, 1992)

Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (Condon, 1995)

Candyman: Day of the Dead (Meyer, 1999)

Candyman (DaCosta, 2021)

*For a little while, I worked at the largest Whole Foods in the Midwest, all of three blocks from the former location of the projects. This little while managed to coincide with my first-ever viewing of Candyman, which probably shaped my response to the movie more than you'll get me to admit.

Let's not dick around here: Candyman is the finest American horror film of the 1990s. Now, admittedly, those who've been hanging around this blog for all that long are aware that for me to make this claim of superiority is about on par with declaring something "the finest swift kick to the nutsack". But I promise that my enthusiasm has much more do with the quantity of things that Candyman gets right than with the general poverty of its competition.

Adapted by writer-director Bernard Rose from Clive Barker's short story "The Forbidden", Candyman centers upon a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen), researching urban legends for her thesis. One of these legends involves a ghostly killer with a hook for a hand, who appears when you say his name, "Candyman", in front of a mirror five times. A cleaning woman happens to overhear Helen transcribing her notes, and talks about the story in a much more matter-of-fact way than the giggling undergrads swapping campfire tales, mentioning among other particularly concrete details that the Candyman is known to haunt the Cabrini-Green housing project on the city's north side. And so Helen and her research partner Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons) head up to the dangerous gang hub to poke around and find what they can find.

That's barely even the set-up for the movie, but it's already enough to clue us in to exactly what makes Candyman such an unusual achievement. In changing the setting from Barker's native England to Chicago and Cabrini-Green, Rose fundamentally re-shapes the territory that the story can occupy. The no-longer-extant Cabrini-Green, my younger readers may not know and my non-American readers would have no reason to be aware, was arguably the most notoriously dangerous and mismanaged housing project in the United States, a shorthand for urban blight, the inability of civic governments to do right by their communities, and the abysmal failure of white America to care about the fate of black America, and to generally assume that African-Americans were, when left to their own devices, prone towards violent thuggery. Setting a story in Cabrini-Green, in 1992 (three years before the beginning of the 16 year demolition project that has sought to reclaim the area for upper-middle class yuppies*), could not help but force that story to refocus itself as a statement on race in America. I would go so far as to say that's the primary reason why somebody would choose that location.

And lo! quite a parable about the U.S. race problem Candyman proves to be, though it has the luxury, being a horror film, of never having to come right out and say what's going on. But subtle it ain't. There is, for one thing, the backstory of the Candyman himself (played by Tony Todd when we eventually see him, around halfway through the movie): the son of a slave, tortured and burned to death for the crime of having a consensual sexual relation with a white woman in the 1890s. He is the angry patron spirit of every African-American male who was unjustly punished for the crime, essentially, of not being white. And what happens over the course of the plot? A white chick bumbles around in a place where she doesn't fit in, does what seems to be the right thing (she ends up uncovering the identity of a local gangleader who has been using the Candyman legend as a fear tactic, all Scooby-Doo like), but her actions - born in the pretty explicit conception of Cabrini-Green as a whole breeding ground of Others that she can use as intellectual fodder without having to deal too much with the actual material of their lives - serve only to make things worse, since her actions are what end up rousing the Candyman. As he tells her, point blank, if she wasn't so hellbent on taking away the power of his legend by running it through academia, he wouldn't have to put in such extreme measures to keep that legend fresh and ever more terrifying.

It is, in microcosm, the great American tale of over-educated white people with no fucking clue messing around with the lives of minorities like a kid with a lab kit, to disastrous results. It is, in fact, pretty obvious once you start looking for it. But the film takes the privilege of genre and never bothers to state its themes in the way of an actual message movie (which is perhaps why it gets to have such a cynical message that so signally refuses to lets its white characters off the hook. Although, the film is rather notable for how few important white characters there are: just Madsen herself, and Xander Berkeley as her husband. Her shady husband, but of course we already knew that from "Xander Berkeley"). And if the only thing you wanted Candyman to be was a horror movie, there's still plenty of fantastic work being done purely at the level of genre. The roots in Barker are clear even without the film's portrayal of the Candyman, with its distinct debt to Pinhead from Hellraiser: it's a film about the terrifying power of ideas, as much as the terrifying power of being split in two by a ghost with a hook for a hand. As one of the first films to pivot around the phrase "urban legend", then at its very trendiest, it's little surprise that Candyman should turn out to be about the dangerous power of storytelling, and the woe that befalls those who don't sufficiently respect that power. We can broaden that a bit: it's a film about failing to appreciate the role of culture, history, and knowledge: Helen ends up on the Candyman's bad side because she treats him as a lark, as opposed to the Cabrini-Green locals, who have a grave respect mingled with their hatred for him.

It's also, to be fair, a horror film that works at a gut level as much as an intellectual one, which is after all where horror needs to succeed. Much of that can be credited to Todd, a great character actor with an outstanding ability to seem menacing while being still and richly erudite. Much of it can be credited to the sound mix, which puts Todd's booming voice on a different level than the rest of the sound in the film, feeling like it's entering your head through something other than your ears. A whole shitload of it can be credited to Philip Glass, whose score is one of the best a horror film has enjoyed since the dawn of the 1980s: the droning repetition for which he's famous works perfectly in context, coming off as a dolorous chant as it throbs and throbs its way down into your bones. Glass is such a natural for horror that I have no clue why there are so few horror movies in his career; it worked magnificently in this case.

Arguably, the single element of Candyman that works best, though, is its sense of place. The location photography here is abnormally good: in the 23 years since, I can't name a half-dozen films to have taken advantage of Chicago anywhere near as well, and perhaps only one - The Dark Knight - to have topped it. The film opens with a series of aerial shots, with Glass's music brooding beneath, that start off by rendering Chicago as a flat, indecipherable map of lines and squares that only resemble buildings if you deeply want them to, putting us at into a disconcerting mood right from the beginning (is this an American city? An alien planet? Why not both!). The footage shot in Cabrini-Green, meanwhile, takes superb advantage of the run-down bleakness of that place, portraying it as a victim of human mismanagement that has been turned into something totally inhumane, an unnervingly authentic hellhole where it feels entirely plausible that such forgotten, hidden legends as the one the film builds itself on could survive and thrive.

Given such an extraordinarily suggestive central location, the film gets to do a lot with mood and implication, letting story elements bubble up without having to spell them out. I am particularly fond of the production design in the Candyman shrine - which I presume to have been shot on a studio set back in California - where the full range of Candyman lore is indicated through the paintings on the wall and the plates of chocolates with razor blades in them, but never explained. It suggests a deep background to this story, one that we and Helen never begin to tap or understand, and that lack of understanding is the driving force of everything bad that happens. Candyman is, essentially, a horror film about the danger of confident ignorance, whether that comes in the form of blithely accepting your husband's obvious lies about the undergrad he's fucking, or in the form of trying to reason with a vengeful ghost, or in the form of thinking you can know more about a lifestyle than the people who live it every day. It's brainy, it's atmospheric, and it's spooky as hell, and for all these reasons and more, Candyman is one of the essential works of modern English-language horror.

Reviews in this series

Candyman (Rose, 1992)

Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (Condon, 1995)

Candyman: Day of the Dead (Meyer, 1999)

Candyman (DaCosta, 2021)

*For a little while, I worked at the largest Whole Foods in the Midwest, all of three blocks from the former location of the projects. This little while managed to coincide with my first-ever viewing of Candyman, which probably shaped my response to the movie more than you'll get me to admit.

Categories: horror, mysteries, scary ghosties, shot in chicago