Seal of approval, or: Taking a selkie, or: Irish I could have come up with more bad puns

To begin by asking the least burning question of them all: is Song of the Sea better than The Secret of Kells? I'm inclined to say no. There's the ol' "form follows content" argument, which would have it that Kells uses a visual aesthetic that is intimately derived from its primary subject, the illuminated Book of Kells; Song of the Sea doesn't look quite exactly the same, but it's extremely close, and it lacks the same tight connection between style subject. Besides, when The Secret of Kells came out, it was like nothing else I'd ever seen. Song of the Sea is like one thing I've ever seen. Which makes it, like, half as original.

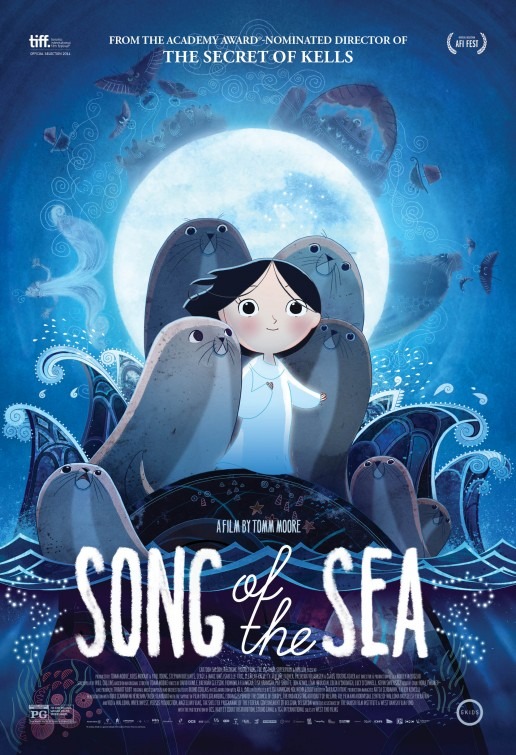

But small-minded pedantry aside, Song of the Sea is still absolutely astounding, a more than worthy follow-up for director Tomm Moore and studio Cartoon Saloon, the creators of Kells. Once again, the action takes place under the shadow of Irish folklore, though Song of the Sea departs from its predecessor by taking place in something close but maybe not quite equal to the modern day (the closest thing to a giveaway is the presence of a handheld cassette player in two scenes). It's the story of two siblings: Ben (David Rawle), bitterly resentful that his now six-year-old sister came into the world the same night that his beloved mother (Lisa Hannigan) left it; and Saoirse, who does not speak, and is the sole focal point of anything resembling emotional engagement from the kids' father Conor (Brendan Gleeson), though it only resembles it a little bit. The lot of them live alone on an island a short boat trip from the Irish coast, tending a lighthouse, and in Saoirse's case, staring with rapt attention at the population of seals that has arrived in those waters for the first time in many years.

The reason for this is not merely that the seals are unbearably goddamn cute - they are, though cuter still is Ben's big sloppy sheepdog Cú - but that Saoirse, it turns out, is half-selkie, and her and Ben's mother was a full selkie, which has something to do with why she disappeared (this theoretically means that Ben, too, is half-selkie, but as the design makes clear, he takes after his father). And what, pray tell, is a selkie? those of you unversed in North Sea folklore are perhaps asking. The short answer is a kind of were-seal. The long answer, in this film's telling, is that the selkie is the link between water and land, and she must sing her songs while wearing her selkie coat in order to keep the fierce Owl Witch at bay. Since Saoirse doesn't speak, and since Conor has taken great lengths to keep her coat hidden, this proves to be a bit a of a problem. Even moreso when an apparent accident on the night that Saoirse first manifests as a selkie leads her bossy grandmother (Fionnula Flanagan) decides that the children need to be taken to her home in Dublin for their own safety.

It is, in truth, basic children's fantasy boilerplate, buoyed up at the narrative level more because Will Collins script, from Moore's story, is full of flippant humor than because it is very surprising, and deepened more from the richness of the voice acting than the probing writing. And I think the filmmakers know this - that, in fact, they were deliberately writing something simple and uncomplicated so that its mythic elements would be more richly accessible. For it's a love letter to Irish folklore through and through; that, and a series of impressions and variations on a theme by Miyazaki Hayao (there's unexpectedly rich veins of Spirited Away in the film's bones), played on Gaelic instruments. Its relative spareness as a work of screenwriting is clearly tied into that desire to make something with the simple clarity of a fairy tale - a characteristic it shares with The Secret of Kells - though with a more complex moral code based on the fervent belief that everybody is ultimately trying to good, it's simply that not everybody necessarily understands how to do that (the film's most overtly Miyazakian element).

I run the risk of selling the film short: it achieves its storytelling goals beautifully, sketching out characters with a few key personality traits that get developed as they move through the disconnected sketches of adventure. I do not mind saying that as it drew to its conclusion, I spontaneously began to well up with some manner of proto-tears. The important thing to keep in mind, is whatever its appeal or lack to adults, Song of the Sea is a children's movie: an extraordinarily good one. Almost certainly the best of 2014. And it has the elemental storytelling of a bedtime story, something that it flags for us from literally the first minutes, which are about the telling of a bedtime story.

Meanwhile, it is breathtakingly beautiful - if I am being honest, probably more beautiful on the level of pure color and shape than Kells. The opening sequence is fuzzy and almost chalky-looking, suggesting the mural painted by mother and son to share the story of the selkie with the unborn baby; the remainder is crisp, brightly-saturated colors with flat shapes and spaces: this movie is unabashedly proud to be two-dimensional. It copies the salient aspect of Kells, mixing side views with overhead views that make a hash of perspective lines and three-dimensional geography; a trick Moore and company picked up from medieval art. And again, it's not entirely clear where the relationship between the style and the story here lies. other than a few moments that hearken back to that opening mural, the aesthetic feels not quite perfect: a little too primitive to actually feel like picturebook illustration, which sometimes appears to be the intent. Or perhaps I'm simply too ignorant of Irish folk art to know what I'm looking at, which I frankly prefer to believe.

For regardless of how well it "fits", Song of the Sea is simply too gorgeous for words. The characters have just a trace of anime influence in their eyes and faces, the backgrounds are wildly abstracted using the distinctive lines and stylised representations of Celtic illuminations. There's not a single frame that isn't lovely, regardless of what else is going on: whether it's funny, adorable, spooky (which happens surprisingly, and gratifyingly, often), or even if it's in one of the film's handful of patchy, slowed-down moments where the folktale structure works against its best interests. It's very special film; in love with its characters, its story, the traditions underpinning that story; and allowing the characters to be full of love and warmth themselves. I'd be a damn liar to call it perfect or particularly innovative, but it's the kind of comfortingly challenging work that represents cinema animation at its most ambitious, and a simply lovely, tender drama on top of it.

But small-minded pedantry aside, Song of the Sea is still absolutely astounding, a more than worthy follow-up for director Tomm Moore and studio Cartoon Saloon, the creators of Kells. Once again, the action takes place under the shadow of Irish folklore, though Song of the Sea departs from its predecessor by taking place in something close but maybe not quite equal to the modern day (the closest thing to a giveaway is the presence of a handheld cassette player in two scenes). It's the story of two siblings: Ben (David Rawle), bitterly resentful that his now six-year-old sister came into the world the same night that his beloved mother (Lisa Hannigan) left it; and Saoirse, who does not speak, and is the sole focal point of anything resembling emotional engagement from the kids' father Conor (Brendan Gleeson), though it only resembles it a little bit. The lot of them live alone on an island a short boat trip from the Irish coast, tending a lighthouse, and in Saoirse's case, staring with rapt attention at the population of seals that has arrived in those waters for the first time in many years.

The reason for this is not merely that the seals are unbearably goddamn cute - they are, though cuter still is Ben's big sloppy sheepdog Cú - but that Saoirse, it turns out, is half-selkie, and her and Ben's mother was a full selkie, which has something to do with why she disappeared (this theoretically means that Ben, too, is half-selkie, but as the design makes clear, he takes after his father). And what, pray tell, is a selkie? those of you unversed in North Sea folklore are perhaps asking. The short answer is a kind of were-seal. The long answer, in this film's telling, is that the selkie is the link between water and land, and she must sing her songs while wearing her selkie coat in order to keep the fierce Owl Witch at bay. Since Saoirse doesn't speak, and since Conor has taken great lengths to keep her coat hidden, this proves to be a bit a of a problem. Even moreso when an apparent accident on the night that Saoirse first manifests as a selkie leads her bossy grandmother (Fionnula Flanagan) decides that the children need to be taken to her home in Dublin for their own safety.

It is, in truth, basic children's fantasy boilerplate, buoyed up at the narrative level more because Will Collins script, from Moore's story, is full of flippant humor than because it is very surprising, and deepened more from the richness of the voice acting than the probing writing. And I think the filmmakers know this - that, in fact, they were deliberately writing something simple and uncomplicated so that its mythic elements would be more richly accessible. For it's a love letter to Irish folklore through and through; that, and a series of impressions and variations on a theme by Miyazaki Hayao (there's unexpectedly rich veins of Spirited Away in the film's bones), played on Gaelic instruments. Its relative spareness as a work of screenwriting is clearly tied into that desire to make something with the simple clarity of a fairy tale - a characteristic it shares with The Secret of Kells - though with a more complex moral code based on the fervent belief that everybody is ultimately trying to good, it's simply that not everybody necessarily understands how to do that (the film's most overtly Miyazakian element).

I run the risk of selling the film short: it achieves its storytelling goals beautifully, sketching out characters with a few key personality traits that get developed as they move through the disconnected sketches of adventure. I do not mind saying that as it drew to its conclusion, I spontaneously began to well up with some manner of proto-tears. The important thing to keep in mind, is whatever its appeal or lack to adults, Song of the Sea is a children's movie: an extraordinarily good one. Almost certainly the best of 2014. And it has the elemental storytelling of a bedtime story, something that it flags for us from literally the first minutes, which are about the telling of a bedtime story.

Meanwhile, it is breathtakingly beautiful - if I am being honest, probably more beautiful on the level of pure color and shape than Kells. The opening sequence is fuzzy and almost chalky-looking, suggesting the mural painted by mother and son to share the story of the selkie with the unborn baby; the remainder is crisp, brightly-saturated colors with flat shapes and spaces: this movie is unabashedly proud to be two-dimensional. It copies the salient aspect of Kells, mixing side views with overhead views that make a hash of perspective lines and three-dimensional geography; a trick Moore and company picked up from medieval art. And again, it's not entirely clear where the relationship between the style and the story here lies. other than a few moments that hearken back to that opening mural, the aesthetic feels not quite perfect: a little too primitive to actually feel like picturebook illustration, which sometimes appears to be the intent. Or perhaps I'm simply too ignorant of Irish folk art to know what I'm looking at, which I frankly prefer to believe.

For regardless of how well it "fits", Song of the Sea is simply too gorgeous for words. The characters have just a trace of anime influence in their eyes and faces, the backgrounds are wildly abstracted using the distinctive lines and stylised representations of Celtic illuminations. There's not a single frame that isn't lovely, regardless of what else is going on: whether it's funny, adorable, spooky (which happens surprisingly, and gratifyingly, often), or even if it's in one of the film's handful of patchy, slowed-down moments where the folktale structure works against its best interests. It's very special film; in love with its characters, its story, the traditions underpinning that story; and allowing the characters to be full of love and warmth themselves. I'd be a damn liar to call it perfect or particularly innovative, but it's the kind of comfortingly challenging work that represents cinema animation at its most ambitious, and a simply lovely, tender drama on top of it.