Cold hearts

There's no good in hiding the obvious: director Nuri Bilge Ceylan's seventh feature Winter Sleep, winner of the 2014 Palme d'Or, is three hours and sixteen minutes long, with most of that time given to people talking. This is a shallow observation, but the film emphasises the weight of its running time to an extreme degree even for the 3-Hours-and-Over club; it has an inexorable quality, marching towards its destination with slow, heavy steps, all the better to focus our attention on the unyielding psychological gamesmanship at its center. You feel that 196 minutes, but the film is not trying to prevent you from doing so.

We are all friends here, so I will risk coming off as a philistine by floating the possibility that Winter Sleep doesn't really earn that running time. It hasn't any denser conversations, nor is it more reliant on making the audience feel duration, than the director's last picture, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, which winsomely clocked in at just 157 minutes (and, for good measure, it's the more interestingly shot of the two films with much fresher and more challenging themes, but if we start playing the "you won the Palme for the wrong movie" game, I might as well give up on the review now). Its repetitions are hardly pointless - they're designed to show how the characters can fail to observe their own behavior and therefore fail to take steps to correct themselves - but they are, nonetheless, repetitions, and it is a lot of movie, when all is said and done.

Anyway, let's meet those characters. Aydin (Haluk Bilginer) is our protagonist; he owns a hotel in a remote, hilly part of the Cappadocia region of Anatolia in Turkey, as well as several properties he rents out to local farmers, he writes an editorial column in the local paper, and he clearly supposes that all of this makes him the hottest of shit. We're invited to see through this pretty quickly in moments that reveal him to be a little bit pathetic: the way he allows his assistant Hidayet (Ayberk Pekcan) to deal with his irate tenants, the fatuous way he has of talking to the guests at his hotel, and his genial bullying demeanor to everyone, whom he plainly regards as the intellectually diminished serfs inhabiting his remote fiefdom. Though most everybody appears to regard him as something of an ass, the only people who call him on it are the women sharing his home: his recently divorced sister Necla (Demet Akbag), and his young-enough-to-be-mistaken-for-his-daughter wife Nihal (Melisa Sözen), who each get their turns in the film's longest individual scenes to try and talk him down to size, to which he responds with some withering erudition of his own; in a movie dominated by slow moments and conversation, these two epic-scale dialogues count as the biggest setpieces.

The script, written by Ceyland and his wife, Ebru Ceylan (this epic-length study of a strained marriage in its death throes must have been the funnest family project ever), plays a lot more fair than just painting Aydin as as blustering know-it-all who needs to get knocked down a peg. It's quite free with observing, in a very subdued and entirely nonjudgmental register, the ways in which all of its characters act with a degree of unthinking arrogance, relative to their position. Nihal may be uniquely capable of outflanking Aydin, but one of the film's strongest individual moments finds her repeating his smugly patriarchal tendency to look down on the poorer classes as things to be attended to, not humans to be engaged with. The film's not merely an indictment of blind male authority, or the assumption of power by the educated and moneyed classes, though both of these things are primary targets. Overall, though, Winter Sleep sets its horizons much broader than that; it is, fundamentally, about disconnects between people, born in arrogance that takes all sorts of different forms, not just the overt ones represented by Aydin. Though he is certainly the most openly self-deluding member of the cast, able to skillfully argue about religion, morality, relationships between people, and all the other things discussed at length throughout the movie, but always more for the sake of arguing than because he clearly understands or cares for what he's talking about.

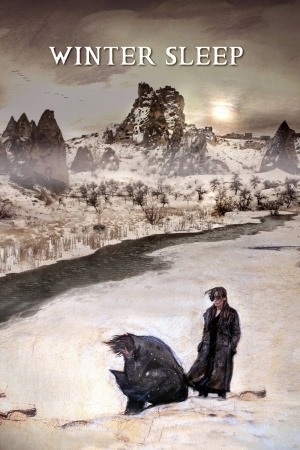

In telling this story, Ceylan situates his characters against a nearly primordial landscape of enormous rocks against which human dwellings nestle incongruously, as the titular winter lays a chilly grey pall over everything even before the snow falls with its metaphoric inevitability. It is a world in which human concerns are weirdly out of place, making the doggedness with which the characters pursue and relentlessly define those concerns, seem even more self-defeating. Aydin's disregard for everyone he claims as his inferiors, and their disregard for him, are mirrored in the way that the landscape seems utterly indifferent to everyone in it. Tellingly, the exteriors are almost always wide shots, stressing the openness of the scenery and minimising the humans in the frame, while the interiors are all closed-in and boxy, giving no sense of the geography within the buildings they occupy; the human element of the film is always conditional in a way that the natural setting isn't.

It's powerful stuff, no two ways about it; and yet, I left Winter Sleep feeling a bit detached from it. The sheer volume of film has a lot to do with that, of course: conversations that are all individually interesting and enlightening both about the human condition and the mental state of the persons having those conversations get a lot less interesing and a lot less enlightening when they wear one down through sheer glut. It's also hard to shake the feeling that it's a decisive step down from Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, which used lighting, framing, and editing with a consistent precision that isn't nearly so true of Winter Sleep. It is bold filmmaking and screenwriting, beyond a shadow of a doubt, with at least two absolutely terrific performances (Bilginer's and Sözen) rising out of a top-level ensemble. But it's tinged by the disappointment that comes from a work of art that's so close to greatness that its failure to quite bridge that last little gap is all the more frustrating.

We are all friends here, so I will risk coming off as a philistine by floating the possibility that Winter Sleep doesn't really earn that running time. It hasn't any denser conversations, nor is it more reliant on making the audience feel duration, than the director's last picture, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, which winsomely clocked in at just 157 minutes (and, for good measure, it's the more interestingly shot of the two films with much fresher and more challenging themes, but if we start playing the "you won the Palme for the wrong movie" game, I might as well give up on the review now). Its repetitions are hardly pointless - they're designed to show how the characters can fail to observe their own behavior and therefore fail to take steps to correct themselves - but they are, nonetheless, repetitions, and it is a lot of movie, when all is said and done.

Anyway, let's meet those characters. Aydin (Haluk Bilginer) is our protagonist; he owns a hotel in a remote, hilly part of the Cappadocia region of Anatolia in Turkey, as well as several properties he rents out to local farmers, he writes an editorial column in the local paper, and he clearly supposes that all of this makes him the hottest of shit. We're invited to see through this pretty quickly in moments that reveal him to be a little bit pathetic: the way he allows his assistant Hidayet (Ayberk Pekcan) to deal with his irate tenants, the fatuous way he has of talking to the guests at his hotel, and his genial bullying demeanor to everyone, whom he plainly regards as the intellectually diminished serfs inhabiting his remote fiefdom. Though most everybody appears to regard him as something of an ass, the only people who call him on it are the women sharing his home: his recently divorced sister Necla (Demet Akbag), and his young-enough-to-be-mistaken-for-his-daughter wife Nihal (Melisa Sözen), who each get their turns in the film's longest individual scenes to try and talk him down to size, to which he responds with some withering erudition of his own; in a movie dominated by slow moments and conversation, these two epic-scale dialogues count as the biggest setpieces.

The script, written by Ceyland and his wife, Ebru Ceylan (this epic-length study of a strained marriage in its death throes must have been the funnest family project ever), plays a lot more fair than just painting Aydin as as blustering know-it-all who needs to get knocked down a peg. It's quite free with observing, in a very subdued and entirely nonjudgmental register, the ways in which all of its characters act with a degree of unthinking arrogance, relative to their position. Nihal may be uniquely capable of outflanking Aydin, but one of the film's strongest individual moments finds her repeating his smugly patriarchal tendency to look down on the poorer classes as things to be attended to, not humans to be engaged with. The film's not merely an indictment of blind male authority, or the assumption of power by the educated and moneyed classes, though both of these things are primary targets. Overall, though, Winter Sleep sets its horizons much broader than that; it is, fundamentally, about disconnects between people, born in arrogance that takes all sorts of different forms, not just the overt ones represented by Aydin. Though he is certainly the most openly self-deluding member of the cast, able to skillfully argue about religion, morality, relationships between people, and all the other things discussed at length throughout the movie, but always more for the sake of arguing than because he clearly understands or cares for what he's talking about.

In telling this story, Ceylan situates his characters against a nearly primordial landscape of enormous rocks against which human dwellings nestle incongruously, as the titular winter lays a chilly grey pall over everything even before the snow falls with its metaphoric inevitability. It is a world in which human concerns are weirdly out of place, making the doggedness with which the characters pursue and relentlessly define those concerns, seem even more self-defeating. Aydin's disregard for everyone he claims as his inferiors, and their disregard for him, are mirrored in the way that the landscape seems utterly indifferent to everyone in it. Tellingly, the exteriors are almost always wide shots, stressing the openness of the scenery and minimising the humans in the frame, while the interiors are all closed-in and boxy, giving no sense of the geography within the buildings they occupy; the human element of the film is always conditional in a way that the natural setting isn't.

It's powerful stuff, no two ways about it; and yet, I left Winter Sleep feeling a bit detached from it. The sheer volume of film has a lot to do with that, of course: conversations that are all individually interesting and enlightening both about the human condition and the mental state of the persons having those conversations get a lot less interesing and a lot less enlightening when they wear one down through sheer glut. It's also hard to shake the feeling that it's a decisive step down from Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, which used lighting, framing, and editing with a consistent precision that isn't nearly so true of Winter Sleep. It is bold filmmaking and screenwriting, beyond a shadow of a doubt, with at least two absolutely terrific performances (Bilginer's and Sözen) rising out of a top-level ensemble. But it's tinged by the disappointment that comes from a work of art that's so close to greatness that its failure to quite bridge that last little gap is all the more frustrating.