The lights that stop me

There is much to be argued for simple things done well. I present for your approval Beyond the Lights, a backstage melodrama and love story that invents nothing, does not surprise, and is still one of the most rewarding films to come out (and then almost immediately vanish) in the waning months of 2014. Blame an tiny distributor without the means to push it hard, blame marketers who are skittish about pushing movies about non-white people for mass consumption, blame the disfavor of audiences towards anything that feels even a little bit like a soap opera. Regardless of who to blame, the film deserves so much more than it's gotten or will ever get: this is not world-changing cinema, but it's satisfying like few movie remember how to be.

The beginning sets the stage for all that follows: Macy Jean (Minnie Driver) is an angry stage mother, and her tween daughter Noni (India Jean-Jacques) is a gifted singer with a retiring and accommodating personality. When we meet the pair of them, it's to learn that Macy has a hard time comprehending this thing that is her daughter: she can't figure out how to do anything with mixed-raced Noni's hair, and practically throws her at a thoroughly unimpressed hairdresser (Deidrie Henry, packing enormous detail and racially-aware backstory into a role that takes up a grand total of two scenes) to solve this problem for her. One second-place finish later, and the tyrant mother vows to her daughter and the heavens that they'll never settle for second-best again.

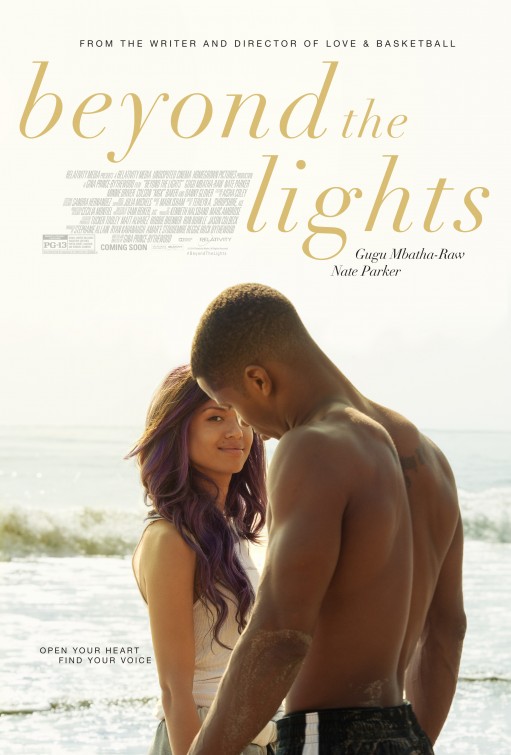

Skip ahead to the present day, and Noni (now played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw) is a genuine musical superstar, winning a Billboard award for her collaboration with Kid Culprit (rapper Machine Gun Kelly, credited under his given name of Richard Colson Baker), a musical artist whose leering lyrics and pelvic dancing are like a lab-created experiment in distilling rape culture. And this before she has even released one single solo track. But though she has everything, and her mother is as happy about it as a pig in shit, Noni is miserable with what she does, who she has to be in order to do it, and the hope she has of ever doing anything else. And so she prepares to throw herself off a hotel balcony in Los Angeles. She's saved only by the quick work of Kaz Nicol (Nate Parker), a cop who took a night working the celebrity security detail for some easy money. Having finally met a person who responds to her as a woman in pain, Noni starts to make excuses to see Kaz more often, and soon enough, romance is in the air, or at least far more tender and mutually rewarding sex than she's been used to. Macy is pissed, and Kaz's father (Danny Glover) is even more pissed, since this threatens to derail his son's political aspirations, but you know how it goes with gorgeous young people in movies about secret emotional pain.

It's all thoroughly generic, but writer-director Gina Prince-Bythewood, making her third feature in 14 years, commits to her story completely, without either talking down to it, or apologising for it. It's every inch a melodrama, but a melodrama that treats the characters, situations, and emotions with ragged naturalism in the filmmaking and acting alike, not with florid escapism. The result is a film that has all the pleasures of melodrama (sweeping emotions, big moments, hot people making out) without any of the histrionics - even Driver's Macy, a snarling monster of a mother for much of the film, is written and played with one foot in kitchen sink realism, built out of desperation and fear for the future and not just slovenly, trashy greed.

The greatest pleasure, though, is Mbatha-Raw, in her second leading performance of her big debutante year (I haven't yet seen Belle, the first, but based on what she does here, I want to). The woman has a commanding ability to play for the camera, making every moment smaller and smaller, pulling us in and making for a more intimate act of character building: the whole performance is a masterful combination of small glances, little details of body position, carefully chosen stresses in her line deliveries. Prince-Bythewood's script and the tonal balances she achieves are already terrific at exploring topics concerning the sexualisation of women in entertainment, the way that money doesn't buy happiness, the torments of mother-daughter relationships built around a power struggle, and the film could certainly be interesting on those fronts with anybody. But Mbatha-Raw's performance isn't an "anybody" sort of thing: she takes all of the film's concepts and sociology and filters it into the lived experience of one single damaged person trying to determine what she wants her identity to be, who functions beautifully as an individual and an embodiment of The Trouble Facing Women Today. It's a simply terrific performance in every respect, a fully-formed Star Is Born moment as exhilarating as the one Noni receives in the film.

On the back of that performance, Beyond the Lights could be much worse and still work. But the fact of the matter is, it's biggest "problem" is predictability in the general shape of things, and rather than using that as a crutch, the writer-director uses that as a tool to guide us into the emotional truths she wants to depict. It's hard to imagine how this stock material could be treated in a more adult, satisfying manner than it is here. This is sturdy, rather than clever filmmaking and storytelling, but sturdiness is a virtue, especially in service to such a convincing, engaging character study of a young woman in turmoil. The vogue for this kind of well-crafted romantic is by no means at a high ebb, but Beyond the Lights demonstrates with crowd-pleasing earnestness and hard indie film seriousness just how effective and necessary the oft-derided world of chick flicks can be.

The beginning sets the stage for all that follows: Macy Jean (Minnie Driver) is an angry stage mother, and her tween daughter Noni (India Jean-Jacques) is a gifted singer with a retiring and accommodating personality. When we meet the pair of them, it's to learn that Macy has a hard time comprehending this thing that is her daughter: she can't figure out how to do anything with mixed-raced Noni's hair, and practically throws her at a thoroughly unimpressed hairdresser (Deidrie Henry, packing enormous detail and racially-aware backstory into a role that takes up a grand total of two scenes) to solve this problem for her. One second-place finish later, and the tyrant mother vows to her daughter and the heavens that they'll never settle for second-best again.

Skip ahead to the present day, and Noni (now played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw) is a genuine musical superstar, winning a Billboard award for her collaboration with Kid Culprit (rapper Machine Gun Kelly, credited under his given name of Richard Colson Baker), a musical artist whose leering lyrics and pelvic dancing are like a lab-created experiment in distilling rape culture. And this before she has even released one single solo track. But though she has everything, and her mother is as happy about it as a pig in shit, Noni is miserable with what she does, who she has to be in order to do it, and the hope she has of ever doing anything else. And so she prepares to throw herself off a hotel balcony in Los Angeles. She's saved only by the quick work of Kaz Nicol (Nate Parker), a cop who took a night working the celebrity security detail for some easy money. Having finally met a person who responds to her as a woman in pain, Noni starts to make excuses to see Kaz more often, and soon enough, romance is in the air, or at least far more tender and mutually rewarding sex than she's been used to. Macy is pissed, and Kaz's father (Danny Glover) is even more pissed, since this threatens to derail his son's political aspirations, but you know how it goes with gorgeous young people in movies about secret emotional pain.

It's all thoroughly generic, but writer-director Gina Prince-Bythewood, making her third feature in 14 years, commits to her story completely, without either talking down to it, or apologising for it. It's every inch a melodrama, but a melodrama that treats the characters, situations, and emotions with ragged naturalism in the filmmaking and acting alike, not with florid escapism. The result is a film that has all the pleasures of melodrama (sweeping emotions, big moments, hot people making out) without any of the histrionics - even Driver's Macy, a snarling monster of a mother for much of the film, is written and played with one foot in kitchen sink realism, built out of desperation and fear for the future and not just slovenly, trashy greed.

The greatest pleasure, though, is Mbatha-Raw, in her second leading performance of her big debutante year (I haven't yet seen Belle, the first, but based on what she does here, I want to). The woman has a commanding ability to play for the camera, making every moment smaller and smaller, pulling us in and making for a more intimate act of character building: the whole performance is a masterful combination of small glances, little details of body position, carefully chosen stresses in her line deliveries. Prince-Bythewood's script and the tonal balances she achieves are already terrific at exploring topics concerning the sexualisation of women in entertainment, the way that money doesn't buy happiness, the torments of mother-daughter relationships built around a power struggle, and the film could certainly be interesting on those fronts with anybody. But Mbatha-Raw's performance isn't an "anybody" sort of thing: she takes all of the film's concepts and sociology and filters it into the lived experience of one single damaged person trying to determine what she wants her identity to be, who functions beautifully as an individual and an embodiment of The Trouble Facing Women Today. It's a simply terrific performance in every respect, a fully-formed Star Is Born moment as exhilarating as the one Noni receives in the film.

On the back of that performance, Beyond the Lights could be much worse and still work. But the fact of the matter is, it's biggest "problem" is predictability in the general shape of things, and rather than using that as a crutch, the writer-director uses that as a tool to guide us into the emotional truths she wants to depict. It's hard to imagine how this stock material could be treated in a more adult, satisfying manner than it is here. This is sturdy, rather than clever filmmaking and storytelling, but sturdiness is a virtue, especially in service to such a convincing, engaging character study of a young woman in turmoil. The vogue for this kind of well-crafted romantic is by no means at a high ebb, but Beyond the Lights demonstrates with crowd-pleasing earnestness and hard indie film seriousness just how effective and necessary the oft-derided world of chick flicks can be.