Nun the wiser

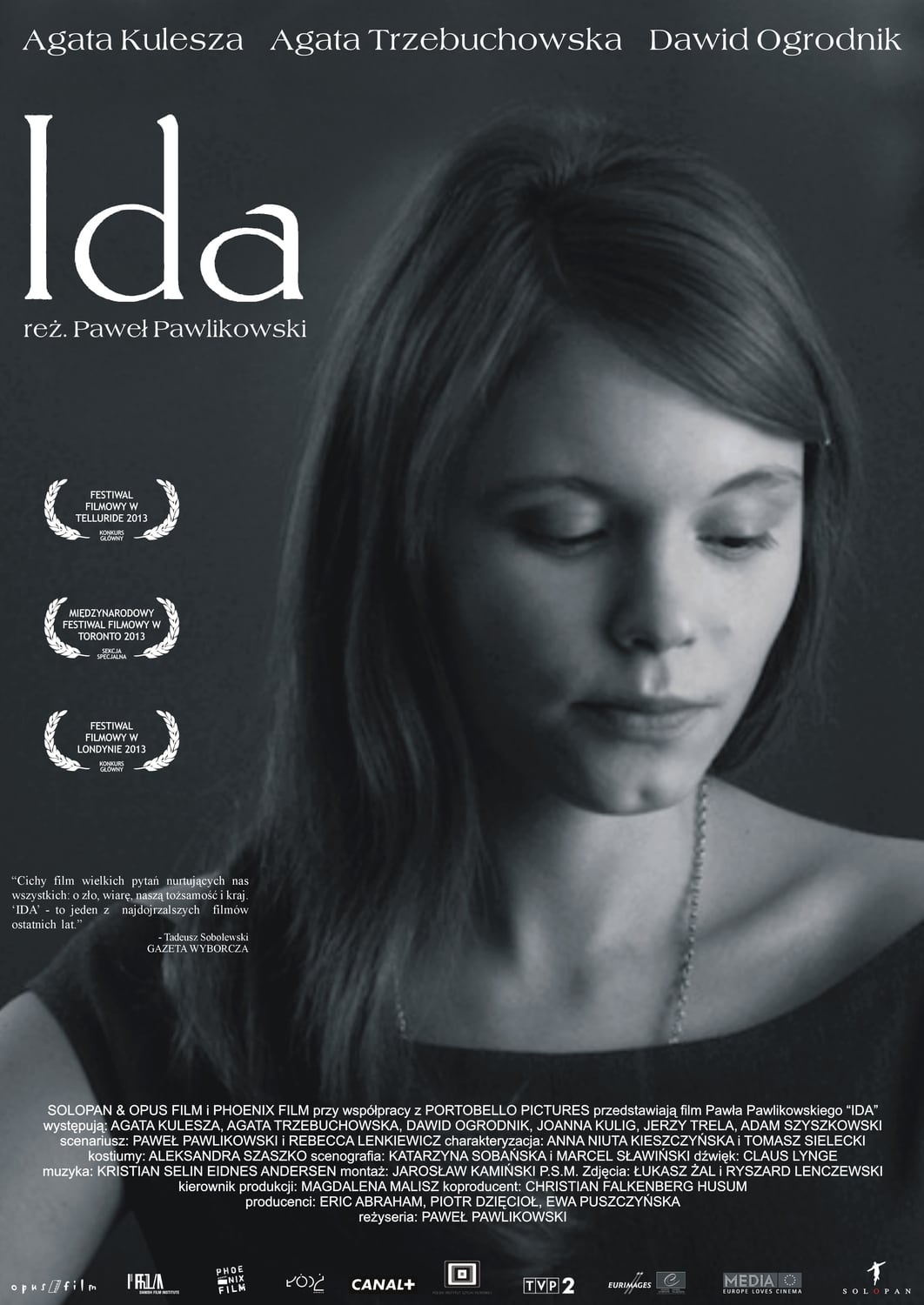

Everything about Ida sounds like it was copied verbatim from the Big Book of European Art Film Clichés: full-frame black and white cinematography with emphasis on the whole range of greys, frequently silent people staring mirthlessly and hopelessly at nothing, the Holocaust looms imposingly in the background, and the whole thing is a metaphor for the silence, absence, or death of God. Small wonder that people have fallen over themselves comparing it to the work of Ingmar Bergman, though it's not always the most apt comparison (there's as much Bresson as Bergman, and arguably more Tarkovsky than either of them, and that's just considering the Big 3 "religious torment" art directors of the '60s and '70s).

And if there's nothing about the film that's necessarily fresh, it's indisputably the case that the things the film is up to haven't been done with so much care and artistry and sophistication are things that haven't been done like this in a lot of years. The fifth narrative feature directed by Paweł Pawlikowski, and also the first made in his native Poland, finds him working at a sublimely confident level that blows away even the quiet potency of his outstanding 2004 My Summer of Love, the closest thing he's had to a prominent film prior to now. Ida, to begin with, solves the thorniest of problems, ones that most films of this sort give up on before they even try to start solving it: how can we use this visual medium of ours to dramatise internal struggles? Even without getting into the question of what it's depicting, I'm steadily impressed by how the film depicts things, using heavily off-kilter framings and precise gradations of hue to guide our eyes and explain the emotional relationships between characters, or between characters and the space surrounding them. It's so clear and high-impact that in its 82 minutes, it has more clearly laid out a more complex psychological journey than films twice as long.

A simple story for a powerful but ultimately direct aesthetic: Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is a novice in a Polish convent, sometime in the early 1960s. She is instructed by her Mother Superior (Halina Skoczyńska) that, before she may take her vows, she must meet with her long-lost aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a bitter judge, formerly a model Communist before alcohol and self-loathing took over. With disinterest so objective it can't even be considered cruel, Wanda reveals a truth that burns the girl's sense of self to the ground: Anna was born Ida Lebenstein, the child of Jews who were killed by the Nazis, but were first able to hide their daughter with a kindly Catholic family to save her. Thus begins a sobering, dismal road trip, as Anna/Ida and Wanda travel through Poland to find the last resting place of the Lebensteins, so that both women might be able to say their goodbyes. Do you suppose that painful truths about post-War Poland and the two traveling companions are revealed in this process? And how they are!

The biggest single problem I have with Ida is that it would surely have been more important and powerful if it had been made at the time it was set, or at least by the end of the '70s. As it is, with a half-century between the society it depicts and itself, it feels distinctly safe, one of those We Know Now What We Should Have Then period pieces that's just a smidgen too proud of its own hindsight.

Not much of a complaint, though, against a film as beautiful and rich in human feeling as it is ice cold in its depiction of human weakness. Ida takes place in a cold universe, visually and morally: the grey imagery of Ryszard Lenczewski and Łukasz Żal's cinematography presents a wintery feeling of desolation, while the script that Pawlikowski co-wrote with Rebecca Lenkiewicz tells the familiar story of a post-Holocaust society that wants to deal with the horror in its recent past by blocking out every trace of the past. In Anna's own journey and the doubt it stirs up in her, the film raises grim questions about the possibility of marrying material happiness with spiritual fulfillment; taking this cue, the film literalises this conflict by loading itself full of shots with extraordinary amounts of headspace. These images constantly emphasise the space above Anna, signifying maybe the presence of God, or more caustically (for these are very empty headspaces, most of the time), the vacuum left by the absence of God. Or perhaps it's just a way for the film to suggest the emotional desolation of life rebuilding itself after the War. It works either way, really.

To keep things from getting too airy and conceptual and divorced from human feeling, Ida is lucky to have a pair of absolutely superb performances at its center. Trzebuchowska, playing a young woman's confusion at finding her identity ripped away from her, manages to embody a rather difficult psychological concept perfectly; as a woman who has lived apart from the messy, fleshy part of life, only to find herself now confronted with the world outside the convent in all its enticing scariness, she does exemplary work with rather more conventional but also more humane material. As good as she is, though, Kulesza dominates the frame, both because Wanda is the stronger personality of the two, and because she captures the fatigue and constant low-grade anger and cynicism of her character in blunt, and physically outsized ways that are expressive and theatrical without seeming forced or unnatural (that the film is, itself, in no particular way naturalistic helps this performance to land). It is, absolutely, one of the most commanding, empathetic performances I've seen all year. Between them, the two stars force Ida to remain a film about its characters, not its ideas. But those ideas are still deep and sobering, just as those characters are complex and unpredictable in the best ways, and the film containing them is one of the clear highlights of the movie year.

And if there's nothing about the film that's necessarily fresh, it's indisputably the case that the things the film is up to haven't been done with so much care and artistry and sophistication are things that haven't been done like this in a lot of years. The fifth narrative feature directed by Paweł Pawlikowski, and also the first made in his native Poland, finds him working at a sublimely confident level that blows away even the quiet potency of his outstanding 2004 My Summer of Love, the closest thing he's had to a prominent film prior to now. Ida, to begin with, solves the thorniest of problems, ones that most films of this sort give up on before they even try to start solving it: how can we use this visual medium of ours to dramatise internal struggles? Even without getting into the question of what it's depicting, I'm steadily impressed by how the film depicts things, using heavily off-kilter framings and precise gradations of hue to guide our eyes and explain the emotional relationships between characters, or between characters and the space surrounding them. It's so clear and high-impact that in its 82 minutes, it has more clearly laid out a more complex psychological journey than films twice as long.

A simple story for a powerful but ultimately direct aesthetic: Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is a novice in a Polish convent, sometime in the early 1960s. She is instructed by her Mother Superior (Halina Skoczyńska) that, before she may take her vows, she must meet with her long-lost aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a bitter judge, formerly a model Communist before alcohol and self-loathing took over. With disinterest so objective it can't even be considered cruel, Wanda reveals a truth that burns the girl's sense of self to the ground: Anna was born Ida Lebenstein, the child of Jews who were killed by the Nazis, but were first able to hide their daughter with a kindly Catholic family to save her. Thus begins a sobering, dismal road trip, as Anna/Ida and Wanda travel through Poland to find the last resting place of the Lebensteins, so that both women might be able to say their goodbyes. Do you suppose that painful truths about post-War Poland and the two traveling companions are revealed in this process? And how they are!

The biggest single problem I have with Ida is that it would surely have been more important and powerful if it had been made at the time it was set, or at least by the end of the '70s. As it is, with a half-century between the society it depicts and itself, it feels distinctly safe, one of those We Know Now What We Should Have Then period pieces that's just a smidgen too proud of its own hindsight.

Not much of a complaint, though, against a film as beautiful and rich in human feeling as it is ice cold in its depiction of human weakness. Ida takes place in a cold universe, visually and morally: the grey imagery of Ryszard Lenczewski and Łukasz Żal's cinematography presents a wintery feeling of desolation, while the script that Pawlikowski co-wrote with Rebecca Lenkiewicz tells the familiar story of a post-Holocaust society that wants to deal with the horror in its recent past by blocking out every trace of the past. In Anna's own journey and the doubt it stirs up in her, the film raises grim questions about the possibility of marrying material happiness with spiritual fulfillment; taking this cue, the film literalises this conflict by loading itself full of shots with extraordinary amounts of headspace. These images constantly emphasise the space above Anna, signifying maybe the presence of God, or more caustically (for these are very empty headspaces, most of the time), the vacuum left by the absence of God. Or perhaps it's just a way for the film to suggest the emotional desolation of life rebuilding itself after the War. It works either way, really.

To keep things from getting too airy and conceptual and divorced from human feeling, Ida is lucky to have a pair of absolutely superb performances at its center. Trzebuchowska, playing a young woman's confusion at finding her identity ripped away from her, manages to embody a rather difficult psychological concept perfectly; as a woman who has lived apart from the messy, fleshy part of life, only to find herself now confronted with the world outside the convent in all its enticing scariness, she does exemplary work with rather more conventional but also more humane material. As good as she is, though, Kulesza dominates the frame, both because Wanda is the stronger personality of the two, and because she captures the fatigue and constant low-grade anger and cynicism of her character in blunt, and physically outsized ways that are expressive and theatrical without seeming forced or unnatural (that the film is, itself, in no particular way naturalistic helps this performance to land). It is, absolutely, one of the most commanding, empathetic performances I've seen all year. Between them, the two stars force Ida to remain a film about its characters, not its ideas. But those ideas are still deep and sobering, just as those characters are complex and unpredictable in the best ways, and the film containing them is one of the clear highlights of the movie year.