Hollywood Century, 1994: In which the attempt to make genre filmmaking more prestigious has mixed results

The first half of the 1990s were the worst time ever to be a fan of horror. Even the stretches of time where horror films weren't being made were better, since at least the absence of horror is preferable to the virtually uninterrupted stream of shit that was North American genre filmmaking in the era between the death of the slashers and the birth of ironic, knowingly bad meta-horror. The Italian exploitation film industry was dying off around the same time, the Japanese horror renaissance was still waiting in the wings, and while there were occasional great horror films, they are vividly notable for their isolation.

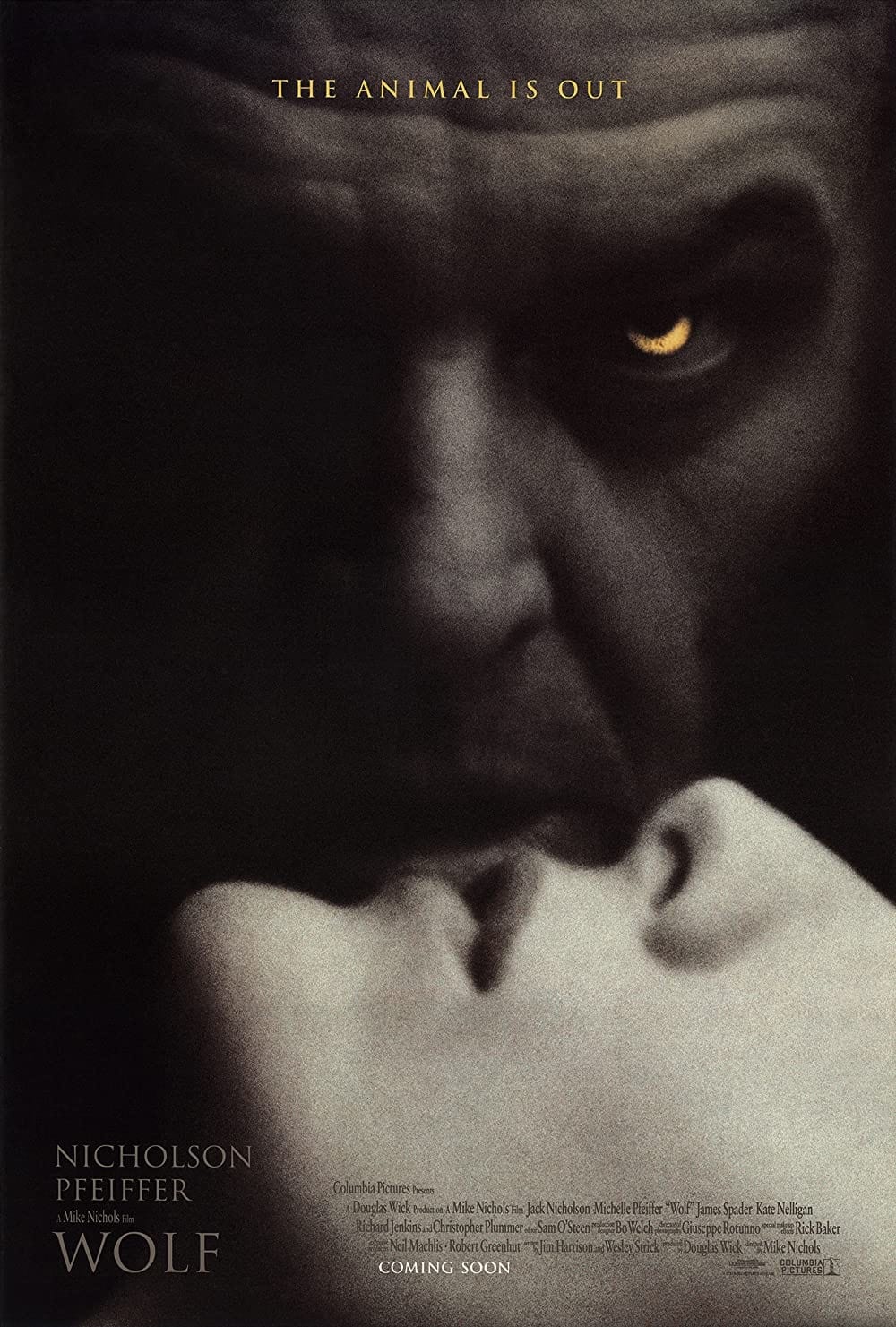

Perhaps because of this vacuum, and perhaps owing solely to an accident of history, the same period bore witness to a compact but highly visible run of classy, literary horror films, more interested in dramatic integrity, filmmaking style, and costume film trappings. The first was Francis Ford Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula, in 1992, whose success was the obvious inspiration for Kenneth Branagh's Mary Shelley's Frankenstein two years later; I'm not certain if it's accurate to say that it specifically led to the release, also in 1994, of Wolf, or in 1996, of Mary Reilly (the latter a tony variant on Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde), but it certainly smoothed the path for adult dramas with horror elements that are too damn-ass tasteful to really deserve the name "horror".

The outlier among these, and maybe the best (I admire many of the artistic impulses behind BS Dracula, but there's an awful lot going abysmally wrong with it), is Wolf; the only one without a literary antecedent, the only one set in contemporary times, and, importantly, the only one that didn't actually belong in the 1990s at all. In fact, it had been stuck in development hell for over a decade by the time it saw the light of day, having originated in the aftermath of the two big werewolf hits of 1981, An American Werewolf in London and The Howling. It is my speculation and nothing else that, when Columbia saw how much Coppola had been able to make for them by doing a glamorous riff on Universal's old monster movies, they leaped at the first grown-up werewolf picture that came along, and that happened to be the Jim Harrison/Wesley Strick script that Jack Nicholson had been infatuated with for years.

Wolf is so goddamn aloof about genre that it never once in two hours even goes so far as to use the world "werewolf" (the writers go to some pains to avoid any lines of dialogue where the absence of that word would become obvious). But that's absolutely what it is: one night, Will Randall (Nicholson), the editor-in-chief of some mid-level New York publishing firm, hits a wolf with his car as he drives from the country back into the city. The animal opens its uncommonly intelligent eyes just as Will gets down to see if it's alive, and bites his hand. This has the immediate effect of giving the saggy old pushover a new lease on life: instead of silently taking it as he's pushed to a bullshit job by Raymond Alden (Christopher Plummer), the billionaire taking over the publishing company, he launches a crafty, brutal plan to not only keep his position but significantly expand his powers. His vision is improved, his hearing and smell have gone far beyond human norms, and his libido is insatiable, to the tremendous delight of his wife Charlotte (Kate Nelligan), though since she's already been having an affair with Will's protégé and replacement, Stewart Swinton (James Spader), this doesn't go terribly well for her, not when her husband can literally smell her lover on her skin. But with his new vitality and increasingly youthful pallor, Will switches right over to Alden's rebellious, caustic adult daughter Laura (Michelle Pfeiffer).

All that is the more immediate effect. The longer-term effect involves Will's tendency to grow hair on his face when he sleeps, and to wake up covered in blood and no memories. When he's lucky, it comes from a deer. When he's not lucky, he hears about it on the news the next day. His consultations with folklorist Dr. Vijay Alezais (Om Puri) confirm his suspicions, and give him a ticking time bomb: his condition will set in permanently at the next full moon, and he will be in wolf form forever, unless, he keeps an amulet next to his skin at all times. But during his jealous rage, Will happened to bite Swinton, and the other man is far too self-aggrandising and awful to be a morally-centered, guilt-ridden wolfman like Will, which will make the latter man's attempts at keeping himself human much, much harder.

The very noticeable thing about Wolf is that it cleaves into two almost equally-sized halves: The Wolf Is a Metaphor, and No, the Wolf Is an Actual Wolf. The former is infinitely preferable, for the simple reason that everybody involved in making the film is clearly happier to be making it. But especially, I think, director Mike Nichols, whose best work occupies exactly the sweet spot that drives the first half: sardonic comedy and satire of the lies and social politics between individual humans. Nothing else he ever made hints at even the most glancing interest in making a monster movie, and Wolf is a very dispirited one: everything that's interesting is interesting solely at the level of the writing (the film's idiosyncratic werewolf lore is interesting enough to cover many other sins) and the acting. But the staging of the big werewolf fight climax is lazy and disengaged, with no sense of drama no matter how urgently Ennio Morricone's appallingly bland score tries to promise that it's all very exciting and tense. And the most openly horror-oriented moments - Will's confrontation with a gang of thugs one night (which triggers a latter response scene involving one of the most tone-deaf examples of white filmmakers trying to aplogise for any possible racial misrepresentation in the whole of the 1990s), the run-up to the final fight - are among its most unconvincing and sloppy.

Far better when the film operates on a purely metaphorical level: what would it mean for a man to be a wolf in New York's professional world? The film's answer to that question is surprisingly slick and clever, aided by what may very well be Jack Nicholson's single best performance of the 1990s*: in a role seemingly tailor-made for Jack Doing a Jack, with the flourishes and elaborate nonsense that entails, he's astoundingly tamped-down. There's coolness and predatory calculation behind his eyes that he virtually never lets loose. It's not merely a strong performance of the part as such, it gains intensity from our awareness of how much energy Nicholson isn't emitting, which then seems to be all caught up inside. There are other strong performances, and as the other main characters, Pfeiffer and Spader are in excellent form playing their stock roles (the outspoken woman in charge of her sexuality, and the conniving yuppie monster), but that's simply not as impressive as Nicholson breaking his persona in such consistent, interesting ways.

The performances provide a suitable foundation for an enjoyably smart, cynical thriller on office power plays, and the emphatically '90s form in which that takes place. Will openly and explicitly feels out of his time, and is convinced that the world is going to hell all around him; the glossy tech-focused world is one that he feels helpless in, until he is suddenly able to master it by becoming a devouring carnivore. It's a fine little fable of business world mores that has the gross misfortune to turn into a horror film at a time when nobody quite knew what horror was, and the people making the satiric thriller clearly thought themselves above it, regardless. The actors survive the shift well (in fact, it's only once the film starts to delve into horror tropes that Pfeiffer's really able to make sense of her weirdly-motivated character), but nothing else does: not the tone, not the wit, not the elegance of the filmmaking. I don't know, exactly, whether to call it a film that almost works or a film that almost fails, because it's balanced perfectly on that razor's edge; it is, though, a film that definitely grows increasingly frustrating as it moves on, and nobody ever wants that.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1994

-Disney puts a bizarre spin on the holidays with the sitcommy The Santa Clause

-Robert Zemeckis's sprawling portrait of Americana Forrest Gump is, to date, the last character drama to win the annual box office

-The old "violence in art" debate hits new heights of panic and outrage over Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1994

-Jackie Chan stars in Drunken Master II, the most beloved of his mid-period films

-The sweet and surprisingly delicate drag queen comedy The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is a watershed moment in the fortunes of Australian commercial cinema

-The future cult comedy Andaz Apna Apna is released in India

Perhaps because of this vacuum, and perhaps owing solely to an accident of history, the same period bore witness to a compact but highly visible run of classy, literary horror films, more interested in dramatic integrity, filmmaking style, and costume film trappings. The first was Francis Ford Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula, in 1992, whose success was the obvious inspiration for Kenneth Branagh's Mary Shelley's Frankenstein two years later; I'm not certain if it's accurate to say that it specifically led to the release, also in 1994, of Wolf, or in 1996, of Mary Reilly (the latter a tony variant on Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde), but it certainly smoothed the path for adult dramas with horror elements that are too damn-ass tasteful to really deserve the name "horror".

The outlier among these, and maybe the best (I admire many of the artistic impulses behind BS Dracula, but there's an awful lot going abysmally wrong with it), is Wolf; the only one without a literary antecedent, the only one set in contemporary times, and, importantly, the only one that didn't actually belong in the 1990s at all. In fact, it had been stuck in development hell for over a decade by the time it saw the light of day, having originated in the aftermath of the two big werewolf hits of 1981, An American Werewolf in London and The Howling. It is my speculation and nothing else that, when Columbia saw how much Coppola had been able to make for them by doing a glamorous riff on Universal's old monster movies, they leaped at the first grown-up werewolf picture that came along, and that happened to be the Jim Harrison/Wesley Strick script that Jack Nicholson had been infatuated with for years.

Wolf is so goddamn aloof about genre that it never once in two hours even goes so far as to use the world "werewolf" (the writers go to some pains to avoid any lines of dialogue where the absence of that word would become obvious). But that's absolutely what it is: one night, Will Randall (Nicholson), the editor-in-chief of some mid-level New York publishing firm, hits a wolf with his car as he drives from the country back into the city. The animal opens its uncommonly intelligent eyes just as Will gets down to see if it's alive, and bites his hand. This has the immediate effect of giving the saggy old pushover a new lease on life: instead of silently taking it as he's pushed to a bullshit job by Raymond Alden (Christopher Plummer), the billionaire taking over the publishing company, he launches a crafty, brutal plan to not only keep his position but significantly expand his powers. His vision is improved, his hearing and smell have gone far beyond human norms, and his libido is insatiable, to the tremendous delight of his wife Charlotte (Kate Nelligan), though since she's already been having an affair with Will's protégé and replacement, Stewart Swinton (James Spader), this doesn't go terribly well for her, not when her husband can literally smell her lover on her skin. But with his new vitality and increasingly youthful pallor, Will switches right over to Alden's rebellious, caustic adult daughter Laura (Michelle Pfeiffer).

All that is the more immediate effect. The longer-term effect involves Will's tendency to grow hair on his face when he sleeps, and to wake up covered in blood and no memories. When he's lucky, it comes from a deer. When he's not lucky, he hears about it on the news the next day. His consultations with folklorist Dr. Vijay Alezais (Om Puri) confirm his suspicions, and give him a ticking time bomb: his condition will set in permanently at the next full moon, and he will be in wolf form forever, unless, he keeps an amulet next to his skin at all times. But during his jealous rage, Will happened to bite Swinton, and the other man is far too self-aggrandising and awful to be a morally-centered, guilt-ridden wolfman like Will, which will make the latter man's attempts at keeping himself human much, much harder.

The very noticeable thing about Wolf is that it cleaves into two almost equally-sized halves: The Wolf Is a Metaphor, and No, the Wolf Is an Actual Wolf. The former is infinitely preferable, for the simple reason that everybody involved in making the film is clearly happier to be making it. But especially, I think, director Mike Nichols, whose best work occupies exactly the sweet spot that drives the first half: sardonic comedy and satire of the lies and social politics between individual humans. Nothing else he ever made hints at even the most glancing interest in making a monster movie, and Wolf is a very dispirited one: everything that's interesting is interesting solely at the level of the writing (the film's idiosyncratic werewolf lore is interesting enough to cover many other sins) and the acting. But the staging of the big werewolf fight climax is lazy and disengaged, with no sense of drama no matter how urgently Ennio Morricone's appallingly bland score tries to promise that it's all very exciting and tense. And the most openly horror-oriented moments - Will's confrontation with a gang of thugs one night (which triggers a latter response scene involving one of the most tone-deaf examples of white filmmakers trying to aplogise for any possible racial misrepresentation in the whole of the 1990s), the run-up to the final fight - are among its most unconvincing and sloppy.

Far better when the film operates on a purely metaphorical level: what would it mean for a man to be a wolf in New York's professional world? The film's answer to that question is surprisingly slick and clever, aided by what may very well be Jack Nicholson's single best performance of the 1990s*: in a role seemingly tailor-made for Jack Doing a Jack, with the flourishes and elaborate nonsense that entails, he's astoundingly tamped-down. There's coolness and predatory calculation behind his eyes that he virtually never lets loose. It's not merely a strong performance of the part as such, it gains intensity from our awareness of how much energy Nicholson isn't emitting, which then seems to be all caught up inside. There are other strong performances, and as the other main characters, Pfeiffer and Spader are in excellent form playing their stock roles (the outspoken woman in charge of her sexuality, and the conniving yuppie monster), but that's simply not as impressive as Nicholson breaking his persona in such consistent, interesting ways.

The performances provide a suitable foundation for an enjoyably smart, cynical thriller on office power plays, and the emphatically '90s form in which that takes place. Will openly and explicitly feels out of his time, and is convinced that the world is going to hell all around him; the glossy tech-focused world is one that he feels helpless in, until he is suddenly able to master it by becoming a devouring carnivore. It's a fine little fable of business world mores that has the gross misfortune to turn into a horror film at a time when nobody quite knew what horror was, and the people making the satiric thriller clearly thought themselves above it, regardless. The actors survive the shift well (in fact, it's only once the film starts to delve into horror tropes that Pfeiffer's really able to make sense of her weirdly-motivated character), but nothing else does: not the tone, not the wit, not the elegance of the filmmaking. I don't know, exactly, whether to call it a film that almost works or a film that almost fails, because it's balanced perfectly on that razor's edge; it is, though, a film that definitely grows increasingly frustrating as it moves on, and nobody ever wants that.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1994

-Disney puts a bizarre spin on the holidays with the sitcommy The Santa Clause

-Robert Zemeckis's sprawling portrait of Americana Forrest Gump is, to date, the last character drama to win the annual box office

-The old "violence in art" debate hits new heights of panic and outrage over Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1994

-Jackie Chan stars in Drunken Master II, the most beloved of his mid-period films

-The sweet and surprisingly delicate drag queen comedy The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is a watershed moment in the fortunes of Australian commercial cinema

-The future cult comedy Andaz Apna Apna is released in India

Categories: hollywood century, horror, love stories, thrillers, werewolves