Summer of Blood: Slasher parodies

Camp is one of the hardest things in pop cultural discourse: hard to quite grasp which of a dozen almost identical, but in some crucial way contradictory definitions, cuts to the heart of what it is; hard to explain it once you've seen it, and demonstrate how and why it works the way it does; and on the creative end, hard to execute it well enough to actually be campy, rather than any of the many things that are what camp exists specifically to comment on and refract. If you are camp's master, you can make Female Trouble. But get camp wrong even a little bit, and...

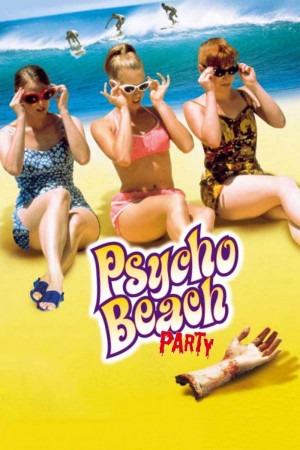

The very concept of camp makes it impossible to use value judgments of "good" and "bad", for it is an inherent part of camp that it resides more within the spectator than in the work of art itself. So with that conceded, I don't actually suppose it means much of anything for me to say that I found Psycho Beach Party to be a completely dismal movie. It is camp run amok, camp that has grown sentient and self-aware and become damnably smug about its own superiority and cleverness. It violates one of the few truly absolute rules I have come up with in all my years of watching movies: no parody is any good unless it comes from a place of love for the object being parodied. Parody that instead perches itself at a level above its target and pitches all of its jokes in the tone of "haha, let's laugh at how shitty this thing is that we're smarter than" is grating tedium, mired in self-congratulation of the worst kind. So perhaps Psycho Beach Party isn't even really camp, for camp is based in affection and love, however unconventionally defined. And while the film is aware of its satiric targets (primarily the American beach movies of the 1960s, secondarily the entire corpus of psycho killer movies), to an admirably exhaustive level of detail and precision, I never once felt even a whisper of love for the genre being parodied or the culture that produced it. Only a deeply satisfied sense that because we have a more sexually sophisticated pop culture than they did around 1959, we are obviously better people than they were.

The 2000 film was adapted by Charles Busch from his own 1987 off-off-Broadway play; a critical 13 years, maybe, which found the mainstream absorbing the aesthetic sensibility of camp and, in the process, defanging it a little bit (if nothing else, a Psycho Beach Party that followed The Brady Bunch Movie to theaters by a full five years couldn't possibly feel as subversive as it probably did when the material was new). There are other, probably more damning problems involved in the stage-to-film transition; I'll return to those. For now, let's crack open the film's plot, which functions as an unexpectedly literal, at times scene-for-scene remake of 1959's Gidget, with a murder mystery sprinkled on top. 1960s SoCal teenager Florence Forrest (Lauren Ambrose) doesn't understand why she's not as interested in sex as her impossibly horny peers seem to be; instead, she finds herself gravitating towards the local surf scene, to the mocking disgust of the surfer Starcat (Nicholas Brendon), who suggests that she's not even a real chick, but a mere "Chicklet", which quickly becomes her nickname. She takes lessons with the surfing sage Kanaka (Thomas Gibson), and starts to feel really peculiar feelings towards Starcat. And all the while, she always seems to be right around when violent murders take place, always during her weird blackouts. Those blackouts also happening to coincide with the emergence of an alternate personality, Ann Bowman, an angry, lewd bondage enthusiast who makes Kanaka her eagerly submissive slave.

Around the edges, we find knowing send-ups of '50s and '60s stock types: Bettina Barnes (Kimberley Davies), a squeaky-voiced movie sexpot with a sensitive, innocent inner life; Berdine (Danni Wheeler), Florence's nerdy best friend and an inconsistently-coded closeted lesbian; Yo Yo (Nick Cornish) and Provoloney (Andrew Levitas), meathead surfers prone to engaging in exaggerated displays of subconscious homoeroticism; and Florence's mother Ruth (Beth Broderick), glassy and glacial in her insistence on putting forth the right June Cleaverish facade, but prone to hitting on the happy, goofy Swedish exchange student Lars (Matt Keeslar) living in her house. I will say this for Psycho Beach Party: it knows its target. Every single performance by its game cast - also including Kathleen Robertson and a pre-stardom Amy Adams, who could be justified in considering this to be an embarrassing skeleton in her closet (she has a partially nude scene) - is absolutely perfect at evoking the ditzy, broad sensibility of the '60s movies being targeted, and Ambrose's ability to switch from a confused but determined Sandra Dee carbon copy to a snarling dominatrix is unimprovable (her third personality, the sassy African-American girl Tylene, is technically accomplished, but suffers from the deeply questionable screenwriting that has a parody of that character type in a movie without any actual black people in it). Robert Lee King's direction reproduces the exact rhythm of the old beach movies, with their flat staging punctuated by flourishes in the scene transitions. The production design and costume design are committed enough that if not for the film stock, it would be visually impossible to tell that this wasn't actually made in the early' 60s.

So in respect of achieving its goals, Psycho Beach Party is absolutely flawless. But I don't know that I can bring myself to say that those goal were worthy of achievement. Setting for oneself as easy a target as the beach movies of the 1960s doesn't mean it's okay to indulge in equally easy jokes, whether it's offensively obvious double-entendres or simplistic "oh, you know this thing was then? Now it's the exact opposite" subversive gags. The homoerotic surf culture the worst in this regard: it's clear by the end of the first scene with the surfers that the joke is that shirtless, muscled young men wrestling each other on the beach reads differently now than it did in the buttoned-up '50s, and this is the only joke that the film thinks it needs to bother with as far as those characters are concerned, and so it repeats that joke every single time they appear, adjusting it only to reiterate it in ever more leaden, literal ways. But it's not fair to pick on one element: damn near every joke telegraphs itself and showcases very little with other than making junior high-level sexual puns. As for the incorporation of the murder mystery, it's not even there to be parodied, only to add a wrinkle to the Gidget framework; though the joke that I thought worked best in the whole film was a visual gag about one of the victim's decapitated head, perhaps an exaggerated version of the "let's show gore!" impulse that has always gone hand-in-hand with psycho killer movies.

I have no idea what Busch changed in transferring his play into cinematic form, though I'd be very surprised if this didn't work better onstage. Watching a movie, the audience is observing the characters; watching theater, the audience is engaging with actors, and this concept seems like it would thrive on that kind of interaction. The wheezing corniness of the jokes and the heightened performances would both, I suspect, land much better in live theater, where the necessary vaudeville or burlesque environment would be more automatically attained just by virtue of having the audience feel like they were in on the joke, not just watching the joke happen.

Also, in the original production, Busch himself played Florence, which would change the energy of the piece so much that I'm at a loss to imagine why it was altered for the movie. Busch felt he was too old to play the part, which is probably fair: he instead took on the part of police captain Monica Stark, a role that makes no sense at the level of anything. She's a parody of the hard-boiled noir detective, except not a single one of those characters was ever a woman, making the parody value muddled at best. As drag, the filmmakers betray the very concept by replacing Busch with a female body double for a sex scene. Meanwhile, having Florence played by a male actor, with her two personalities representing two equally unrealistic extremes of pop cultural feminine psychology, seems so sensible and so central to the way that Psycho Beach Party was conceived as camp that I wish they'd gone ahead with it, still letting Busch play Stark, and just deal with having two cross-dressed roles in one movie.

The entire movie is one long misfire: immaculate execution in every detail of one poor conception after another. I can't call it a failure, because it does everything right except exist. But mean-spirited spoofing at the broadest level possible isn't remotely edifying. The year after this came out, another film came out parodying an already self-parodying comedy genre: Wet Hot American Summer. The only camp thing about that film is its setting, but it's everything that Psycho Beach Party most conspicuously fails to be: an accurate recreation of a terrible form that mocks it from a place of warm familiarity and affection, that stands as an inventive, clever comedy on its own merits. If you want to watch a goofy send-up of goofy teen fare from generations ago, stick with that: its success calls attention to everything about Psycho Beach Party that's uninspired, arrogant, and lazy.

Body Count: 5, depending on what you want to do with the ending.

The very concept of camp makes it impossible to use value judgments of "good" and "bad", for it is an inherent part of camp that it resides more within the spectator than in the work of art itself. So with that conceded, I don't actually suppose it means much of anything for me to say that I found Psycho Beach Party to be a completely dismal movie. It is camp run amok, camp that has grown sentient and self-aware and become damnably smug about its own superiority and cleverness. It violates one of the few truly absolute rules I have come up with in all my years of watching movies: no parody is any good unless it comes from a place of love for the object being parodied. Parody that instead perches itself at a level above its target and pitches all of its jokes in the tone of "haha, let's laugh at how shitty this thing is that we're smarter than" is grating tedium, mired in self-congratulation of the worst kind. So perhaps Psycho Beach Party isn't even really camp, for camp is based in affection and love, however unconventionally defined. And while the film is aware of its satiric targets (primarily the American beach movies of the 1960s, secondarily the entire corpus of psycho killer movies), to an admirably exhaustive level of detail and precision, I never once felt even a whisper of love for the genre being parodied or the culture that produced it. Only a deeply satisfied sense that because we have a more sexually sophisticated pop culture than they did around 1959, we are obviously better people than they were.

The 2000 film was adapted by Charles Busch from his own 1987 off-off-Broadway play; a critical 13 years, maybe, which found the mainstream absorbing the aesthetic sensibility of camp and, in the process, defanging it a little bit (if nothing else, a Psycho Beach Party that followed The Brady Bunch Movie to theaters by a full five years couldn't possibly feel as subversive as it probably did when the material was new). There are other, probably more damning problems involved in the stage-to-film transition; I'll return to those. For now, let's crack open the film's plot, which functions as an unexpectedly literal, at times scene-for-scene remake of 1959's Gidget, with a murder mystery sprinkled on top. 1960s SoCal teenager Florence Forrest (Lauren Ambrose) doesn't understand why she's not as interested in sex as her impossibly horny peers seem to be; instead, she finds herself gravitating towards the local surf scene, to the mocking disgust of the surfer Starcat (Nicholas Brendon), who suggests that she's not even a real chick, but a mere "Chicklet", which quickly becomes her nickname. She takes lessons with the surfing sage Kanaka (Thomas Gibson), and starts to feel really peculiar feelings towards Starcat. And all the while, she always seems to be right around when violent murders take place, always during her weird blackouts. Those blackouts also happening to coincide with the emergence of an alternate personality, Ann Bowman, an angry, lewd bondage enthusiast who makes Kanaka her eagerly submissive slave.

Around the edges, we find knowing send-ups of '50s and '60s stock types: Bettina Barnes (Kimberley Davies), a squeaky-voiced movie sexpot with a sensitive, innocent inner life; Berdine (Danni Wheeler), Florence's nerdy best friend and an inconsistently-coded closeted lesbian; Yo Yo (Nick Cornish) and Provoloney (Andrew Levitas), meathead surfers prone to engaging in exaggerated displays of subconscious homoeroticism; and Florence's mother Ruth (Beth Broderick), glassy and glacial in her insistence on putting forth the right June Cleaverish facade, but prone to hitting on the happy, goofy Swedish exchange student Lars (Matt Keeslar) living in her house. I will say this for Psycho Beach Party: it knows its target. Every single performance by its game cast - also including Kathleen Robertson and a pre-stardom Amy Adams, who could be justified in considering this to be an embarrassing skeleton in her closet (she has a partially nude scene) - is absolutely perfect at evoking the ditzy, broad sensibility of the '60s movies being targeted, and Ambrose's ability to switch from a confused but determined Sandra Dee carbon copy to a snarling dominatrix is unimprovable (her third personality, the sassy African-American girl Tylene, is technically accomplished, but suffers from the deeply questionable screenwriting that has a parody of that character type in a movie without any actual black people in it). Robert Lee King's direction reproduces the exact rhythm of the old beach movies, with their flat staging punctuated by flourishes in the scene transitions. The production design and costume design are committed enough that if not for the film stock, it would be visually impossible to tell that this wasn't actually made in the early' 60s.

So in respect of achieving its goals, Psycho Beach Party is absolutely flawless. But I don't know that I can bring myself to say that those goal were worthy of achievement. Setting for oneself as easy a target as the beach movies of the 1960s doesn't mean it's okay to indulge in equally easy jokes, whether it's offensively obvious double-entendres or simplistic "oh, you know this thing was then? Now it's the exact opposite" subversive gags. The homoerotic surf culture the worst in this regard: it's clear by the end of the first scene with the surfers that the joke is that shirtless, muscled young men wrestling each other on the beach reads differently now than it did in the buttoned-up '50s, and this is the only joke that the film thinks it needs to bother with as far as those characters are concerned, and so it repeats that joke every single time they appear, adjusting it only to reiterate it in ever more leaden, literal ways. But it's not fair to pick on one element: damn near every joke telegraphs itself and showcases very little with other than making junior high-level sexual puns. As for the incorporation of the murder mystery, it's not even there to be parodied, only to add a wrinkle to the Gidget framework; though the joke that I thought worked best in the whole film was a visual gag about one of the victim's decapitated head, perhaps an exaggerated version of the "let's show gore!" impulse that has always gone hand-in-hand with psycho killer movies.

I have no idea what Busch changed in transferring his play into cinematic form, though I'd be very surprised if this didn't work better onstage. Watching a movie, the audience is observing the characters; watching theater, the audience is engaging with actors, and this concept seems like it would thrive on that kind of interaction. The wheezing corniness of the jokes and the heightened performances would both, I suspect, land much better in live theater, where the necessary vaudeville or burlesque environment would be more automatically attained just by virtue of having the audience feel like they were in on the joke, not just watching the joke happen.

Also, in the original production, Busch himself played Florence, which would change the energy of the piece so much that I'm at a loss to imagine why it was altered for the movie. Busch felt he was too old to play the part, which is probably fair: he instead took on the part of police captain Monica Stark, a role that makes no sense at the level of anything. She's a parody of the hard-boiled noir detective, except not a single one of those characters was ever a woman, making the parody value muddled at best. As drag, the filmmakers betray the very concept by replacing Busch with a female body double for a sex scene. Meanwhile, having Florence played by a male actor, with her two personalities representing two equally unrealistic extremes of pop cultural feminine psychology, seems so sensible and so central to the way that Psycho Beach Party was conceived as camp that I wish they'd gone ahead with it, still letting Busch play Stark, and just deal with having two cross-dressed roles in one movie.

The entire movie is one long misfire: immaculate execution in every detail of one poor conception after another. I can't call it a failure, because it does everything right except exist. But mean-spirited spoofing at the broadest level possible isn't remotely edifying. The year after this came out, another film came out parodying an already self-parodying comedy genre: Wet Hot American Summer. The only camp thing about that film is its setting, but it's everything that Psycho Beach Party most conspicuously fails to be: an accurate recreation of a terrible form that mocks it from a place of warm familiarity and affection, that stands as an inventive, clever comedy on its own merits. If you want to watch a goofy send-up of goofy teen fare from generations ago, stick with that: its success calls attention to everything about Psycho Beach Party that's uninspired, arrogant, and lazy.

Body Count: 5, depending on what you want to do with the ending.