Hollywood Century, 1951: In which the most important thing, onscreen and off, is lavish spectale and glitzy, high-class entertainment

There is no spectacle quite like the spectacle of the musicals made by MGM's A-list production unit under producer Arthur Freed. Glowing Technicolor, some of the most talented song-and-dance experts ever put on screen, enormous budgets spent on enormous sets: these are the ingredients to make a lifelong fan of the musical genre. Curiously, the Freed Unit musical is an almost entirely post-war phenomenon, despite the apparent reality that Hollywood movies started to tighten their belts after World War II began - though Freed's credits as a producer at the studio stretch from 1939 to 1962, the Golden Age of the MGM musical is much more constrained, stretching from Meet Me in St. Louis in 1944 till 'round about The Band Wagon in 1953, though you could push it a little farther if you were inclined.

From within that era, I now direct your attention to 1951's Royal Wedding, the solo directorial debut of Stanley Donen, who got the job in the midst of a particularly complicated and bitter shoot, in which professional egos and personal demons made a real hell for everybody. The female lead was set to be June Allyson, a mid-level MGM star at the time, until she got pregnant, and was replaced by Judy Garland, one of the studio's top names, whose chemical regimen at the time made her wildly unpredictable and unreliable. The film's assigned director, Charles Walters, was reluctant to work with her again after their previous experiences together, and the studio dumped him without ceremony; when principal photography began and Garland started missing call times, she was fired - not merely from the project, but from MGM itself, leading to her cutting her neck with glass in a fit of depression. And Garland's story from here on continues melodramatic and sorrowful, but we will leave her for now, for she was replaced in her turn by Jane Powell, 21 years old at the time of production and thrust into the first A-picture of a career that would not include very many A-pictures.

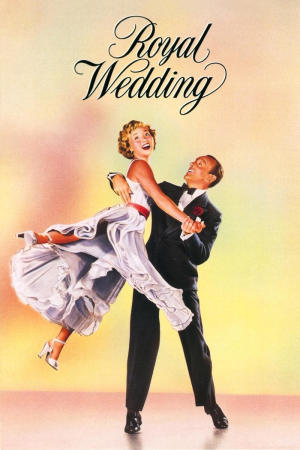

So much drama for a movie that's such a fluffy cupcake. The first and maybe only adjective that Royal Wedding insists upon for itself is "charming": and a kind of sleepy, easy charming it is, too, mostly forgettable outside of a handful of really top-notch musical numbers. As written by Alan Jay Lerner - the stage lyricist's very first movie credit - the story tells of a pair of Broadway superstar siblings, Ellen Bowen (Powell) and her older brother - her much, much older brother - Tom (Fred Astaire, whose relationship with his sister Adele inspired the characters), who are given an opportunity to take their hit show to London just in time for the big wedding of the local princess (the Princess Elizabeth had married Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten had occurred in 1947; they are not named, but it's preposterous to imagine that 1951 audiences wouldn't make the connection). While there, the two Bowens spend more time falling in love than performing: Ellen with the charmingly awkward and poor Lord John Brindale (Peter Lawford), whom she meets on the ship crossing the ocean, Tom with the dancer Anne Ashmond (Sarah Churchill, daughter of the once and future Prime Minister), that he picks up while casting the show. Minor problems intervene, but there's only a very small doubt of how things are going to wind up.

Charming, like I said; charming and really not all that good. Of the four leads, nobody is bad bad, but Astaire is by leaps and bounds the best; Powell suffers mostly from being exorbitantly miscast as the sibling of the 51-year-old Astaire, and there's never a moment where the movie doesn't feel like it could be improved immensely if they'd been re-written as father and daughter, or lovers on the outs. But for all that she's ridiculous opposite her co-star, and for all that she can't sing very well at all (and not in the way that Astaire had a kind of boring, unemphatic singing voice: she can't sing), she had a pretty nifty sense of comic timing; I am terribly in love with how she plays the scene where she enthusiastically tells two lovers - in the same room - that she's about to head across the Atlantic, all addled enthusiasm and talking over herself. And the stock role of the tough "one of the boys" Broadway baby feels a lot more alive and bracing in her hands than it really ought to, by that late date.

But still, the onscreen talent isn't overwhelming. The dances are perfectly fine, but the only two moments than anybody ever pretends to truly care about are both solo Astaire numbers, which can hardly be regarded as an accident. Those being the instrumental "Sunday Jumps", where a bored Tom starts fooling around in the ship's gym, amusing himself by dancing with a handy hat rack; and "You're All the World to Me", where he's so lovestruck that as he sings his passion for Anne to an empty room, he literally dances up the walls and across the ceiling. The fact that I could just name the gimmick of those two numbers and a sizable majority of the people reading this have undoubtedly already called to mind the dances (or at least the vacuum ad made out of the former) is all it takes: these are iconic, madly inventive pieces of choreography and filmmaking, from a time when Astaire had long since run out of things to prove with simple dancing and had begun to push himself to invent new ways of representing dance onscreen. Something must have been in the air at MGM; the same year, Gene Kelly was busily ending An American in Paris with a full-on dream ballet, an impressionistically-edited fantasy that, like Astaire's audacious numbers here, was totally new to the American cinematic musical.

But the thing is, outside of those two unimpeachable highlights, Royal Wedding simply isn't very interesting - the rest of the songs, with lyrics by Lerner and music by Burton Lane, make very little impression (and for that matter, "Sunday Jumps" and "You're All the World to Me" hardly stick in the mind because of the music), and the choreography isn't nearly as inventive anywhere else: the epically-titled "How Could You Believe Me When I Said I Love You When You Know I've Been a Liar All My Life" is basically just a rehash version of "A Couple of Swells" from Easter Parade, and the climactic showstopper "I Left My Hat in Haiti" feels like it was reheated from leftover scraps of a Busby Berkeley narrative number, along the "42nd Street" or "Shanghai Lil" model (it looks ahead to the "tell a short film in dance" finales to several MGM films to come, but is weaker than any of them).

The story, meanwhile, is such a featherweight trifle - and the actors plainly recognise it as such - that it hardly bears bringing it up. Lawford in particular, apparently resigning himself to a completely functional part in a script that doesn't obviously care whether or not it's functioning properly, just seems to exist onscreen, without anything fussy like "character" or "personality" to get in the way of stating his lines clearly and smiling. It's generally amusing and pleasant, but there's no bite to it whatsoever, and no ingenuity: nothing worth quoting, almost nothing even worth laughing aloud at.

But it looks like a million bucks, and it's easy to like, and for Freed, that was what mattered. I think the fact of it being an American movie set at the British royal wedding tells us everything: it's set against a backdrop of opulence, tradition, pageantry, and glamor, that nobody in the target audience has any personal stake in whatsoever. It's all surfaces, and they are delightful, but of the musical's great gift for foreground emotions in moments of greatly expressive non-reality, there is little. The emotions in Royal Wedding are entirely remote, and the charms are entirely fleeting. Astaire aside, nothing here ranks among the truly classic musicals, and taken as a whole, it's forgettable in a way that most of the Freed Unit movies aren't. But you can't win 'em all.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1951

-Chuck Jones begins to shift the Looney Tunes from great comic cartooning into something more like pop art with Rabbit Fire

-Science fiction grows up in a big way with one of the most adult of all genre films, Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still

-Elia Kazan's adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire, starring Marlon Brando, fundamentally shifts the development of screen acting and the nature of movie stars

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1951

-Robert Bresson begins his run of aesthetically and religiously austere dramas in France, with Diary of a Country Priest

-Jean Renoir makes his gorgeous Franco-Indian-American co-production in Technicolor, The River

-The first edition of the Berlin International Film Festival is held in June

From within that era, I now direct your attention to 1951's Royal Wedding, the solo directorial debut of Stanley Donen, who got the job in the midst of a particularly complicated and bitter shoot, in which professional egos and personal demons made a real hell for everybody. The female lead was set to be June Allyson, a mid-level MGM star at the time, until she got pregnant, and was replaced by Judy Garland, one of the studio's top names, whose chemical regimen at the time made her wildly unpredictable and unreliable. The film's assigned director, Charles Walters, was reluctant to work with her again after their previous experiences together, and the studio dumped him without ceremony; when principal photography began and Garland started missing call times, she was fired - not merely from the project, but from MGM itself, leading to her cutting her neck with glass in a fit of depression. And Garland's story from here on continues melodramatic and sorrowful, but we will leave her for now, for she was replaced in her turn by Jane Powell, 21 years old at the time of production and thrust into the first A-picture of a career that would not include very many A-pictures.

So much drama for a movie that's such a fluffy cupcake. The first and maybe only adjective that Royal Wedding insists upon for itself is "charming": and a kind of sleepy, easy charming it is, too, mostly forgettable outside of a handful of really top-notch musical numbers. As written by Alan Jay Lerner - the stage lyricist's very first movie credit - the story tells of a pair of Broadway superstar siblings, Ellen Bowen (Powell) and her older brother - her much, much older brother - Tom (Fred Astaire, whose relationship with his sister Adele inspired the characters), who are given an opportunity to take their hit show to London just in time for the big wedding of the local princess (the Princess Elizabeth had married Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten had occurred in 1947; they are not named, but it's preposterous to imagine that 1951 audiences wouldn't make the connection). While there, the two Bowens spend more time falling in love than performing: Ellen with the charmingly awkward and poor Lord John Brindale (Peter Lawford), whom she meets on the ship crossing the ocean, Tom with the dancer Anne Ashmond (Sarah Churchill, daughter of the once and future Prime Minister), that he picks up while casting the show. Minor problems intervene, but there's only a very small doubt of how things are going to wind up.

Charming, like I said; charming and really not all that good. Of the four leads, nobody is bad bad, but Astaire is by leaps and bounds the best; Powell suffers mostly from being exorbitantly miscast as the sibling of the 51-year-old Astaire, and there's never a moment where the movie doesn't feel like it could be improved immensely if they'd been re-written as father and daughter, or lovers on the outs. But for all that she's ridiculous opposite her co-star, and for all that she can't sing very well at all (and not in the way that Astaire had a kind of boring, unemphatic singing voice: she can't sing), she had a pretty nifty sense of comic timing; I am terribly in love with how she plays the scene where she enthusiastically tells two lovers - in the same room - that she's about to head across the Atlantic, all addled enthusiasm and talking over herself. And the stock role of the tough "one of the boys" Broadway baby feels a lot more alive and bracing in her hands than it really ought to, by that late date.

But still, the onscreen talent isn't overwhelming. The dances are perfectly fine, but the only two moments than anybody ever pretends to truly care about are both solo Astaire numbers, which can hardly be regarded as an accident. Those being the instrumental "Sunday Jumps", where a bored Tom starts fooling around in the ship's gym, amusing himself by dancing with a handy hat rack; and "You're All the World to Me", where he's so lovestruck that as he sings his passion for Anne to an empty room, he literally dances up the walls and across the ceiling. The fact that I could just name the gimmick of those two numbers and a sizable majority of the people reading this have undoubtedly already called to mind the dances (or at least the vacuum ad made out of the former) is all it takes: these are iconic, madly inventive pieces of choreography and filmmaking, from a time when Astaire had long since run out of things to prove with simple dancing and had begun to push himself to invent new ways of representing dance onscreen. Something must have been in the air at MGM; the same year, Gene Kelly was busily ending An American in Paris with a full-on dream ballet, an impressionistically-edited fantasy that, like Astaire's audacious numbers here, was totally new to the American cinematic musical.

But the thing is, outside of those two unimpeachable highlights, Royal Wedding simply isn't very interesting - the rest of the songs, with lyrics by Lerner and music by Burton Lane, make very little impression (and for that matter, "Sunday Jumps" and "You're All the World to Me" hardly stick in the mind because of the music), and the choreography isn't nearly as inventive anywhere else: the epically-titled "How Could You Believe Me When I Said I Love You When You Know I've Been a Liar All My Life" is basically just a rehash version of "A Couple of Swells" from Easter Parade, and the climactic showstopper "I Left My Hat in Haiti" feels like it was reheated from leftover scraps of a Busby Berkeley narrative number, along the "42nd Street" or "Shanghai Lil" model (it looks ahead to the "tell a short film in dance" finales to several MGM films to come, but is weaker than any of them).

The story, meanwhile, is such a featherweight trifle - and the actors plainly recognise it as such - that it hardly bears bringing it up. Lawford in particular, apparently resigning himself to a completely functional part in a script that doesn't obviously care whether or not it's functioning properly, just seems to exist onscreen, without anything fussy like "character" or "personality" to get in the way of stating his lines clearly and smiling. It's generally amusing and pleasant, but there's no bite to it whatsoever, and no ingenuity: nothing worth quoting, almost nothing even worth laughing aloud at.

But it looks like a million bucks, and it's easy to like, and for Freed, that was what mattered. I think the fact of it being an American movie set at the British royal wedding tells us everything: it's set against a backdrop of opulence, tradition, pageantry, and glamor, that nobody in the target audience has any personal stake in whatsoever. It's all surfaces, and they are delightful, but of the musical's great gift for foreground emotions in moments of greatly expressive non-reality, there is little. The emotions in Royal Wedding are entirely remote, and the charms are entirely fleeting. Astaire aside, nothing here ranks among the truly classic musicals, and taken as a whole, it's forgettable in a way that most of the Freed Unit movies aren't. But you can't win 'em all.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1951

-Chuck Jones begins to shift the Looney Tunes from great comic cartooning into something more like pop art with Rabbit Fire

-Science fiction grows up in a big way with one of the most adult of all genre films, Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still

-Elia Kazan's adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire, starring Marlon Brando, fundamentally shifts the development of screen acting and the nature of movie stars

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1951

-Robert Bresson begins his run of aesthetically and religiously austere dramas in France, with Diary of a Country Priest

-Jean Renoir makes his gorgeous Franco-Indian-American co-production in Technicolor, The River

-The first edition of the Berlin International Film Festival is held in June

Categories: comedies, hollywood century, love stories, musicals