Who's the deadliest one of all?

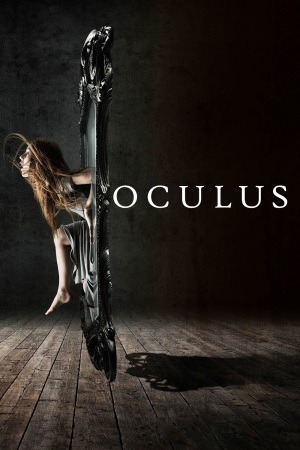

Nearly until the end, and I literally mean, like, up until the last four minutes, Oculus makes a great argument for itself as being the best mainstream horror film since... I guess "since The Conjuring" isn't really at all impressive. But the spirit of my point is clear, yes? It has all the stuff to be a great horror film and it ends up being a very good horror film with some intensely dubious ideas about how to wrap up all of its clever themes and narrative conceits. Given the batting average for the genre, this is more than enough to qualify Oculus as a modern masterpiece the likes of which you'll tell your grandchildren about.

Also, "oculus" is one of those words that barely looks real in the first place, and when you keep typing it just looks more and more fake and ludicrous. Oculus, oculus, oculus.

Anyway, the film is built on a fascinating gambit: it's attempting to develop one core theme, which it does in two somewhat distinct halves that each approach that them from a different perspective. Basically, Oculus is about human perception and memory, and how easy it is to screw with both of those things, and for the first bit of the movie, it explores this in a very talky, script-driven way. The story centers on the Russell siblings, 23-year old Kaylie (Karen Gillan) and 21-year-old Tim (Brenton Thwaites), who have a shared trauma buried eleven years in their past: the facts of the matter are that their father killed their mother, and Tim then shot their father. For Tim, newly released from a psychiatric care facility upon attaining his majority, this event caused such a profound break in his mind, needing to absolve himself of guilt, that he crafted an absurd fantasy to create to protect himself from his own actions, and only years of treatment in a safe space have permitted him to come to grips with the truth. For Kaylie, their dad was possessed by the malevolent spirit living inside a haunted mirror.

Horror cinema being what it is, it's obvious long before Oculus lays its cards on the table which of the siblings will be proven correct, but for a surprisingly lengthy stretch in the first half, the film isn't so much a psychological thriller about the unreliability of memory, as an expository series of dialogues in which the two Russells clearly speak their interpretation of events and go out of their way to poke holes in the other's certitude. The reason this isn't deadly onscreen has a lot to do with the fussiness of the plot happening underneath the speeches: Kaylie has recently tracked down the mirror, and has laid out a phenomenally complex system of safeguards to make sure that she's able to destroy it, with full video evidence to prove that it is haunted, and their dad wasn't a murdering psycho, and the same scenes where the acres of chatter about the unreliability of perception play out are intertwined with her Rube Goldberg theatrics. And, too, it helps that the actors have a certain easy ability to make their jargony conversation feel naturalistic, particularly Gillan, who speaks with a clipped patter that verges on robotic, and by all means shouldn't work; yet it's so heightened and discordant with the rest of the film, like a screwball heroine who landed in a ghost story by mistake, that it's madly captivating.

So that's the first part: open and blunt conversations about how easy it is to convince yourself that something that isn't true actually happened, and how much that framework can inform the way that you interpret what's happening right now. Once the mystery resolves itself, surprisingly early, that yes, the mirror is a demon, the film ceases to explore this theme narratively and begins exploring it structurally: at this point, the film dissolves into a full-on editing freak-out in which the grown-up Russells start to lose track of when they're themselves and when they're the eleven-years-younger versions of themselves. For all throughout, being in the house where all that bad stuff happened so long ago has been triggering flashbacks, as both siblings recall the physical details of what happened to them (Annalise Basso plays young Kaylie, Garrett Ryan plays young Tim), and how they separately perceived the slow descent of their father (Rory Cochrane) into a kind of madness brought on, apparently, by too much exposure to his mirror - or maybe just the shiny-eyed ghosts that hover around it - and the equally inexplicable turn towards cruelty in their mother (Katee Sackhoff). Throughout, these flashbacks have been spliced in through all the normal cues; at a certain point, they start to bleed into the movie proper, with child and adult versions of the characters rushing past each other in the same hallways, and both siblings losing track of what they're looking at, when they're looking at it, and where they are, with the audience increasingly encouraged to lose track as well, thanks to the magic of cross-cutting.

In essence, if the first half of the movie states "your perception is a half-assed jerry-rigged series of shortcuts that you can't trust", the second half demonstrates it by openly flaunting continuity in a way that's terrifically disconcerting and, in a few well-timed moments, even really creepy, as those mirror wraiths pop up and vanish in the best fashion of J-horror knock-offs. And I must congratulate director Mike Flanagan and his co-writer Jeff Howard for so thoroughly balancing psychological concepts with the grubby mechanics of a ghost movie. If anything sucks the wind out of the film, it's that the brunt of this doesn't feel like it adds up to anything; Oculus doesn't end up having any "point" bigger than its sage observation that the demon living in the mirror wants to kill and eat souls, and the grand fandango of themes and psychothriller is just a spectacularly obtuse way of getting at that profoundly limited conceit. It's astonishingly shallow, really, for how many complex ideas it explores with relatively deep thought and success.

But that's not really a problem at all: I went into Oculus expecting a ratty fast-food hamburger of a film and I got a ratty fast-food hamburger of a film, but with a warm home-baked bun and sublime artisan cheese, and those were sufficiently pleasing surprises that I choose to be delighted by their presence, rather than disappointed that the burger itself was still gristly and burnt. The greater problem, the one that I cannot forgive, is that Oculus ends badly - intensely, boringly badly. I have no idea what ending might have worked, but the one that the film went with is as bad an idea as I can imagine, diving with childlike zeal into clichés of the dodgiest sort, resorting a nihilistic "fuck it all!" gesture instead of following up on the real complexities of the script or paying off the moments when it's a generally spooky ghost story. Horror films that work at all well are so rare that I'm not about to write Oculus off because the last few moments are utter trash, but I have to say, the film leaves a spectacularly bitter feeling on the way out.

Also, "oculus" is one of those words that barely looks real in the first place, and when you keep typing it just looks more and more fake and ludicrous. Oculus, oculus, oculus.

Anyway, the film is built on a fascinating gambit: it's attempting to develop one core theme, which it does in two somewhat distinct halves that each approach that them from a different perspective. Basically, Oculus is about human perception and memory, and how easy it is to screw with both of those things, and for the first bit of the movie, it explores this in a very talky, script-driven way. The story centers on the Russell siblings, 23-year old Kaylie (Karen Gillan) and 21-year-old Tim (Brenton Thwaites), who have a shared trauma buried eleven years in their past: the facts of the matter are that their father killed their mother, and Tim then shot their father. For Tim, newly released from a psychiatric care facility upon attaining his majority, this event caused such a profound break in his mind, needing to absolve himself of guilt, that he crafted an absurd fantasy to create to protect himself from his own actions, and only years of treatment in a safe space have permitted him to come to grips with the truth. For Kaylie, their dad was possessed by the malevolent spirit living inside a haunted mirror.

Horror cinema being what it is, it's obvious long before Oculus lays its cards on the table which of the siblings will be proven correct, but for a surprisingly lengthy stretch in the first half, the film isn't so much a psychological thriller about the unreliability of memory, as an expository series of dialogues in which the two Russells clearly speak their interpretation of events and go out of their way to poke holes in the other's certitude. The reason this isn't deadly onscreen has a lot to do with the fussiness of the plot happening underneath the speeches: Kaylie has recently tracked down the mirror, and has laid out a phenomenally complex system of safeguards to make sure that she's able to destroy it, with full video evidence to prove that it is haunted, and their dad wasn't a murdering psycho, and the same scenes where the acres of chatter about the unreliability of perception play out are intertwined with her Rube Goldberg theatrics. And, too, it helps that the actors have a certain easy ability to make their jargony conversation feel naturalistic, particularly Gillan, who speaks with a clipped patter that verges on robotic, and by all means shouldn't work; yet it's so heightened and discordant with the rest of the film, like a screwball heroine who landed in a ghost story by mistake, that it's madly captivating.

So that's the first part: open and blunt conversations about how easy it is to convince yourself that something that isn't true actually happened, and how much that framework can inform the way that you interpret what's happening right now. Once the mystery resolves itself, surprisingly early, that yes, the mirror is a demon, the film ceases to explore this theme narratively and begins exploring it structurally: at this point, the film dissolves into a full-on editing freak-out in which the grown-up Russells start to lose track of when they're themselves and when they're the eleven-years-younger versions of themselves. For all throughout, being in the house where all that bad stuff happened so long ago has been triggering flashbacks, as both siblings recall the physical details of what happened to them (Annalise Basso plays young Kaylie, Garrett Ryan plays young Tim), and how they separately perceived the slow descent of their father (Rory Cochrane) into a kind of madness brought on, apparently, by too much exposure to his mirror - or maybe just the shiny-eyed ghosts that hover around it - and the equally inexplicable turn towards cruelty in their mother (Katee Sackhoff). Throughout, these flashbacks have been spliced in through all the normal cues; at a certain point, they start to bleed into the movie proper, with child and adult versions of the characters rushing past each other in the same hallways, and both siblings losing track of what they're looking at, when they're looking at it, and where they are, with the audience increasingly encouraged to lose track as well, thanks to the magic of cross-cutting.

In essence, if the first half of the movie states "your perception is a half-assed jerry-rigged series of shortcuts that you can't trust", the second half demonstrates it by openly flaunting continuity in a way that's terrifically disconcerting and, in a few well-timed moments, even really creepy, as those mirror wraiths pop up and vanish in the best fashion of J-horror knock-offs. And I must congratulate director Mike Flanagan and his co-writer Jeff Howard for so thoroughly balancing psychological concepts with the grubby mechanics of a ghost movie. If anything sucks the wind out of the film, it's that the brunt of this doesn't feel like it adds up to anything; Oculus doesn't end up having any "point" bigger than its sage observation that the demon living in the mirror wants to kill and eat souls, and the grand fandango of themes and psychothriller is just a spectacularly obtuse way of getting at that profoundly limited conceit. It's astonishingly shallow, really, for how many complex ideas it explores with relatively deep thought and success.

But that's not really a problem at all: I went into Oculus expecting a ratty fast-food hamburger of a film and I got a ratty fast-food hamburger of a film, but with a warm home-baked bun and sublime artisan cheese, and those were sufficiently pleasing surprises that I choose to be delighted by their presence, rather than disappointed that the burger itself was still gristly and burnt. The greater problem, the one that I cannot forgive, is that Oculus ends badly - intensely, boringly badly. I have no idea what ending might have worked, but the one that the film went with is as bad an idea as I can imagine, diving with childlike zeal into clichés of the dodgiest sort, resorting a nihilistic "fuck it all!" gesture instead of following up on the real complexities of the script or paying off the moments when it's a generally spooky ghost story. Horror films that work at all well are so rare that I'm not about to write Oculus off because the last few moments are utter trash, but I have to say, the film leaves a spectacularly bitter feeling on the way out.