Tarr Béla dances with the devil

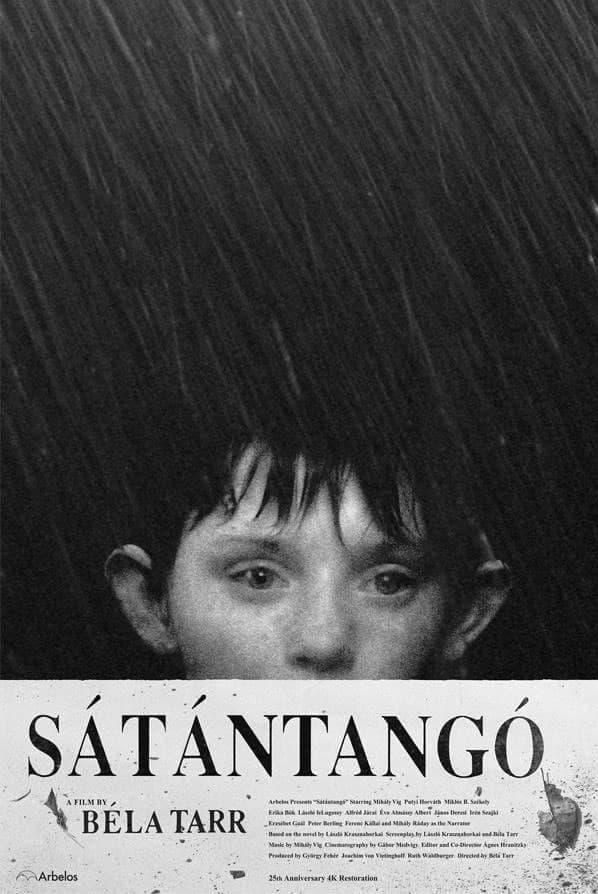

Just the name can send a shiver down the spine of the ill-prepared cinephile. Sátántangó. For Tarr Béla's 7+ hour signature work is one of the endurance tests to tend all endurance tests in the art form of film. It is not the longest movie; even without leaving the realm of (relatively) conventional narrative cinema, we find Out 1 and Berlin Alexanderplatz are significantly longer, right off the top of my head. But neither of them is typically held to a one-day viewing prospect. And neither of them is held to be as massively unpleasant, for after all, neither of them has "Satan" right there in the title.

In honesty, though, Sátántangó's claims to misery are blown substantially out of proportion to it's nihilistic content. Stories of 7-minute opening shots of nothing but cows wandering around in the mud, and little girls poisoning cats that die in disconcertingly realistic long takes are true, by all means, but they tend to obscure the equally true reality that the film is astonishingly, compulsively watchable, attention-grabbing from the first moments and unwilling to relinquish its grip for any part of its hypertrophic running time. Speaking personally, I didn't watch the film in a single sitting - the three discs of the Facets DVD set (which remains the best chance most Americans outside of New York will ever have to see the film) were interspersed with a shower and a meal - but I have virtually no doubt that it would play that way, with enthralling abandon. For all its mass and famously glacial cutting pace - the tally I got was 152 distinct shots over almost precisely seven hours - the film moves, surprisingly quickly.

Let us turn now to that opening shot to see what I mean: we're in a rural town, mud as far as the eye can see, staring down an old building. After some while, cows start to pour out of that building, until eventually a whole herd stands in the street; eventually they start to walk off to the left, and the camera rotates exactly 90° counterclockwise, at which point it starts to track left while the cattle meander through the street; frequently, buildings between us and them obscure the cows from our view, and at one point, a cow that came up right along side us moos irritably as it hustles down an alley on the Z-axis, to rejoin its fellows. I could spend the rest of my life trying to describe that shot in a way that communicates how legitimately exciting it is: how, after a couple of moments following the cows, it becomes impossibly disorienting when we lose sight of them for a good minute behind a structure; how gorgeously Tarr and cinematographyer Medvigy Gábor render the streets, buildings and animals in every stop along the grey scale besides exactly black and exactly white, teasing out so much texture and variability in each and every object that they practically go (setting aside the obvious point that watching a 7-hour movie is a wholly different experience in a theater than in a house: it's been months since I last so a movie that I so desperately wanted to see on a clean, crisp film print). It is beautiful and kinetic, and it's also a perfect introduction to the film in that it basically serves as a quick instruction in how to watch the film: Sátántangó is a movie rich with lateral tracking movements, with right-angle turns, and with gloriously touchable physical tactility those things, and everything that will visually dominate the next 7+ hours of the viewer's life is laid out in simple, easily-digestible terms in that very open shot.

It's also a sneak preview of the themes and narrative of those hours as well. Before they start their tour of the town, the cattle stand in the open street before the building, patiently enduring the mud and looking at nothing in particular. A collection of dumb animals caught in a miserable place and totally unconcerned with the actions that might free them up to go someplace more pleasant: that describes the unknown population of this town to a T, and the plot (insofar as it's the draw, which is certainly a debatable matter) is all about how these bored people are led off to slaughter by a fellow who doesn't even present a particularly appealing or compelling outlook for life: he's' merely the only person offering up any idea for the cows to lumber after.

That person, who fills the role of Satan in this dance, is Irimiás (Vig Mihály, who also provides the film with its electronica-carnival score), who exists in the beginning as an unseen figure viewed by the townspeople with dread that goes far beyond the natural fear of a notorious conman thought to be dead for this past year. "The news is, they're coming" is the title of the first of the film's 12 chapters (six forward, six back, the structure of a tango and the structure of the 1985 source novel written by László , Tarr's collaborator on his previous film, Damnation), which finds the residents of an unnamed communitarian farm that has just about puked out its last drop of life in the waning days of Communist Hungary interrupting the sorry little melodramas of their life with real mortal fear of the impending return of Irimiás and his colleague Petrina (Horváth Putyi). And yet not interrupting their lives so much that don't slink right back into the same patterns of petty double-dealing, lazy adulterous sex, and a detached attempt at spying on one another.

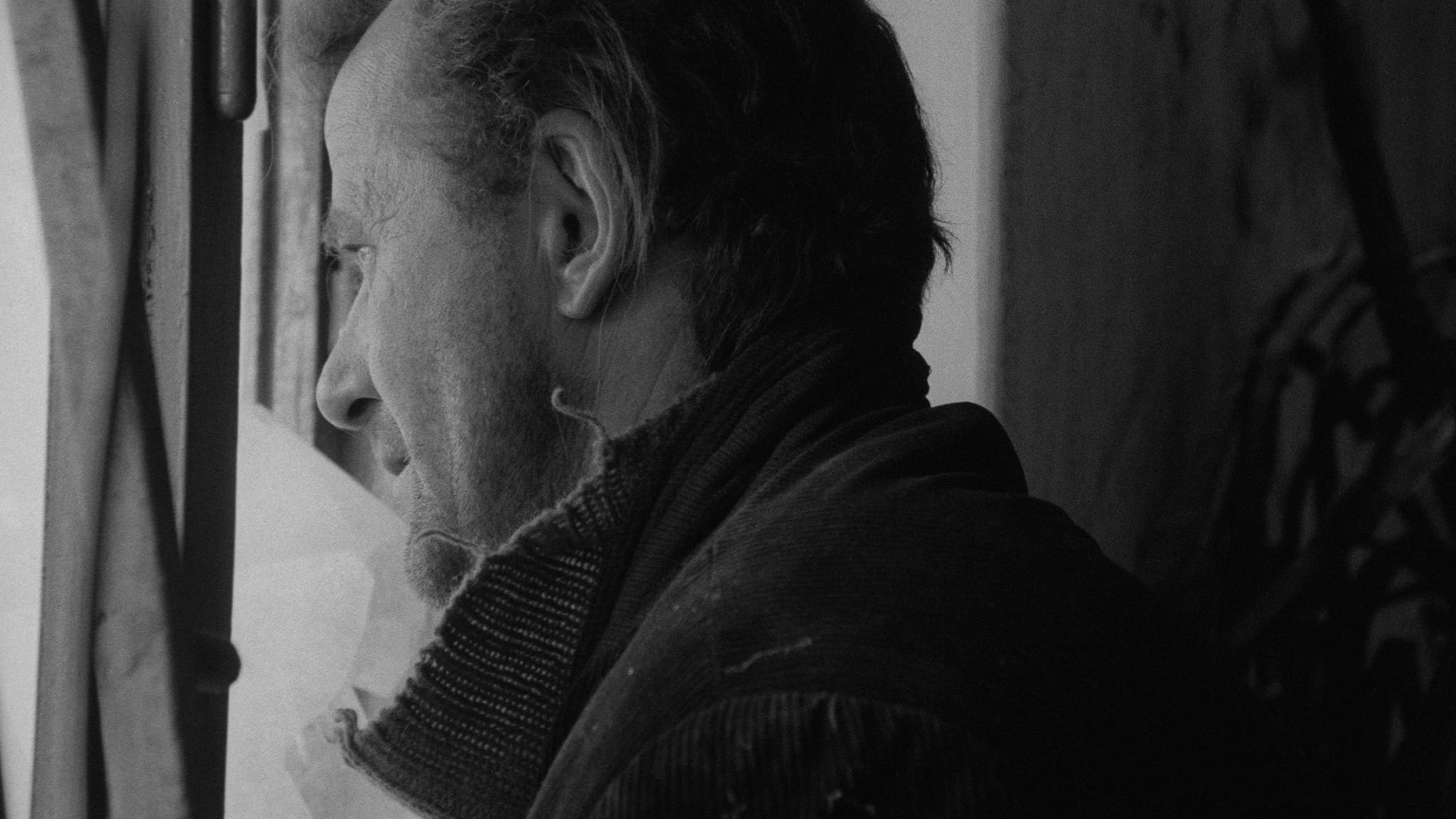

For people who are more or less explicitly being painted as anonymous archetypes, the population of Sátántangó ends up making quite an impression, if only because we spend so damn much time with them that they really don't have an opportunity not to. Tarr, Krasznahorkai and Tarr's reliable co-auteur editor, Hranitzky Ágnes don't depict them as having terribly characteristic personalities and behaviors as such, but by dwelling on the rhythms of their behavior at such length and in such detail, the filmmakers mange to tell us in evocative terms precisely who they are. The resentful loner Futaki (Székely Miklós) waits just so before barging in on the unexpected husband of the woman he's been sleeping with; the drunken doctor (Berling Peter) goes through precisely these actions in precisely this order, and it's easy to tell that he does much the same every day.

By the end of the film, the nine individuals making up most of what's left of the population of the town have made themselves very clear to us: they are pitiable and a bit reprehensible, but Tarr does not look to make any kind of emotional or moral judgment: he merely depicts. What he specifically depicts is the crushing mediocrity of a life stripped of imagination or affect; no living hell like the one scene in Damnation, this is much more of a purgatory of endless muddy, rain, and play-acted emotions. It is the perfect place for Irimiás to sell his obvious and not very compelling lies of another, better but only marginally different, way of living if everybody would just give up their autonomy and self-interest; a metaphor for the dogged refusal of Communism on its death bed to just give up and die that openly indicts the willingness of the people suffering most under that system to keep on suffering out of some mixed combination of comfort and self-laceration. It is both a study of the capacity of humans to do harm to other humans, but also the capacity of humans to bring harm unto themselves; most horrifyingly but also intelligently in the notorious centerpiece that finds the child Estike (Bók Erika) torturing and murdering that cat and then killing herself, precipitating the rest of the action and giving Irimiás the knife to twist into the town's collective psyche, and all because she could find no other way to take control in a world where everyone either ignored or abused her, than by first attacking the one thing weaker than herself and then by taking ownership of her own death.

Grim, weighty, extraordinary stuff, presented by Tarr with remarkable vision and sophistication. It is not merely that Sátántangó creates a complex moral universe, but how - as befits a movie of such gargantuan running time that it would have to do something to fill the space, the movie engages in some remarkable layering of scenes viewed in different chapters from different perspectives, creating a gnarled puzzle box of a movie that doesn't even announce itself as a puzzle until it has shown us the solution. In the fifth chapter, "Come unstitched" we see the interior of a bar in which the adults of the town are drunkenly cavorting in a frenzied dance, from Estike's perspective; in the sixth, "The spider's work II (the devil's nipple, satantango)" we look from inside that noisy, busy room to see the little girl blankly looking in, behind a wall of glass; and as we already know that she's going to die early the next morning, it makes her isolation that much more piercing than the image itself communicates. The film is full of mutually-expressive conversations between shots and scenes, culminating in a climax that queasily but not fatalistically suggests that the while cycle of events is going to repeat itself, albeit with some of the principals dead, exiled, or desperately attempting to entomb themselves in their tiny little worlds, blocking all the light out by boarding up windows (the final shot of the whole movie, a brilliant parody and replacement for the traditional fade to black).

It is dense, rich, and beautiful, a visually challenging movie that uses its long takes not so much to create a reality or to draw us into the world (the blocking is much too stiff and presentational for any of this to seem remotely naturalistic), but so that every one of the cuts feels like a profound moment - a violation or a moment of emotional release, depending on the context, and sometimes both. The slow progression of the film through a relatively full narrative - there are sequences in which the conflict changes multiple times in the span of just one shot - creates a tension that makes the film spectacularly electric and even exciting to watch, a peculiar response to a film that, moment by moment, is so languorous and boring. Not as a whole, though. As a whole, this is anything but boring: it is a whirlwind tour of a whole rainbow of unhappy human emotions, presented with fluidity in the writing, the acting, and the cinematography, and it's surprisingly gripping for something so full of miserable people feeling misery. No film of this length, so fixed on human despair with only shallow, trivial attempts to stave off that despair through drunkenness and cheap sex should trigger a response at the end, "it's not over already, is it?", but that's how you can tell a masterpiece: it turns pain into art and static lives into vibrant, kinetic images, without ever cheapening its subjects in the process. It's a great film, as great as they come, and that's all there is to it.

In honesty, though, Sátántangó's claims to misery are blown substantially out of proportion to it's nihilistic content. Stories of 7-minute opening shots of nothing but cows wandering around in the mud, and little girls poisoning cats that die in disconcertingly realistic long takes are true, by all means, but they tend to obscure the equally true reality that the film is astonishingly, compulsively watchable, attention-grabbing from the first moments and unwilling to relinquish its grip for any part of its hypertrophic running time. Speaking personally, I didn't watch the film in a single sitting - the three discs of the Facets DVD set (which remains the best chance most Americans outside of New York will ever have to see the film) were interspersed with a shower and a meal - but I have virtually no doubt that it would play that way, with enthralling abandon. For all its mass and famously glacial cutting pace - the tally I got was 152 distinct shots over almost precisely seven hours - the film moves, surprisingly quickly.

Let us turn now to that opening shot to see what I mean: we're in a rural town, mud as far as the eye can see, staring down an old building. After some while, cows start to pour out of that building, until eventually a whole herd stands in the street; eventually they start to walk off to the left, and the camera rotates exactly 90° counterclockwise, at which point it starts to track left while the cattle meander through the street; frequently, buildings between us and them obscure the cows from our view, and at one point, a cow that came up right along side us moos irritably as it hustles down an alley on the Z-axis, to rejoin its fellows. I could spend the rest of my life trying to describe that shot in a way that communicates how legitimately exciting it is: how, after a couple of moments following the cows, it becomes impossibly disorienting when we lose sight of them for a good minute behind a structure; how gorgeously Tarr and cinematographyer Medvigy Gábor render the streets, buildings and animals in every stop along the grey scale besides exactly black and exactly white, teasing out so much texture and variability in each and every object that they practically go (setting aside the obvious point that watching a 7-hour movie is a wholly different experience in a theater than in a house: it's been months since I last so a movie that I so desperately wanted to see on a clean, crisp film print). It is beautiful and kinetic, and it's also a perfect introduction to the film in that it basically serves as a quick instruction in how to watch the film: Sátántangó is a movie rich with lateral tracking movements, with right-angle turns, and with gloriously touchable physical tactility those things, and everything that will visually dominate the next 7+ hours of the viewer's life is laid out in simple, easily-digestible terms in that very open shot.

It's also a sneak preview of the themes and narrative of those hours as well. Before they start their tour of the town, the cattle stand in the open street before the building, patiently enduring the mud and looking at nothing in particular. A collection of dumb animals caught in a miserable place and totally unconcerned with the actions that might free them up to go someplace more pleasant: that describes the unknown population of this town to a T, and the plot (insofar as it's the draw, which is certainly a debatable matter) is all about how these bored people are led off to slaughter by a fellow who doesn't even present a particularly appealing or compelling outlook for life: he's' merely the only person offering up any idea for the cows to lumber after.

That person, who fills the role of Satan in this dance, is Irimiás (Vig Mihály, who also provides the film with its electronica-carnival score), who exists in the beginning as an unseen figure viewed by the townspeople with dread that goes far beyond the natural fear of a notorious conman thought to be dead for this past year. "The news is, they're coming" is the title of the first of the film's 12 chapters (six forward, six back, the structure of a tango and the structure of the 1985 source novel written by László , Tarr's collaborator on his previous film, Damnation), which finds the residents of an unnamed communitarian farm that has just about puked out its last drop of life in the waning days of Communist Hungary interrupting the sorry little melodramas of their life with real mortal fear of the impending return of Irimiás and his colleague Petrina (Horváth Putyi). And yet not interrupting their lives so much that don't slink right back into the same patterns of petty double-dealing, lazy adulterous sex, and a detached attempt at spying on one another.

For people who are more or less explicitly being painted as anonymous archetypes, the population of Sátántangó ends up making quite an impression, if only because we spend so damn much time with them that they really don't have an opportunity not to. Tarr, Krasznahorkai and Tarr's reliable co-auteur editor, Hranitzky Ágnes don't depict them as having terribly characteristic personalities and behaviors as such, but by dwelling on the rhythms of their behavior at such length and in such detail, the filmmakers mange to tell us in evocative terms precisely who they are. The resentful loner Futaki (Székely Miklós) waits just so before barging in on the unexpected husband of the woman he's been sleeping with; the drunken doctor (Berling Peter) goes through precisely these actions in precisely this order, and it's easy to tell that he does much the same every day.

By the end of the film, the nine individuals making up most of what's left of the population of the town have made themselves very clear to us: they are pitiable and a bit reprehensible, but Tarr does not look to make any kind of emotional or moral judgment: he merely depicts. What he specifically depicts is the crushing mediocrity of a life stripped of imagination or affect; no living hell like the one scene in Damnation, this is much more of a purgatory of endless muddy, rain, and play-acted emotions. It is the perfect place for Irimiás to sell his obvious and not very compelling lies of another, better but only marginally different, way of living if everybody would just give up their autonomy and self-interest; a metaphor for the dogged refusal of Communism on its death bed to just give up and die that openly indicts the willingness of the people suffering most under that system to keep on suffering out of some mixed combination of comfort and self-laceration. It is both a study of the capacity of humans to do harm to other humans, but also the capacity of humans to bring harm unto themselves; most horrifyingly but also intelligently in the notorious centerpiece that finds the child Estike (Bók Erika) torturing and murdering that cat and then killing herself, precipitating the rest of the action and giving Irimiás the knife to twist into the town's collective psyche, and all because she could find no other way to take control in a world where everyone either ignored or abused her, than by first attacking the one thing weaker than herself and then by taking ownership of her own death.

Grim, weighty, extraordinary stuff, presented by Tarr with remarkable vision and sophistication. It is not merely that Sátántangó creates a complex moral universe, but how - as befits a movie of such gargantuan running time that it would have to do something to fill the space, the movie engages in some remarkable layering of scenes viewed in different chapters from different perspectives, creating a gnarled puzzle box of a movie that doesn't even announce itself as a puzzle until it has shown us the solution. In the fifth chapter, "Come unstitched" we see the interior of a bar in which the adults of the town are drunkenly cavorting in a frenzied dance, from Estike's perspective; in the sixth, "The spider's work II (the devil's nipple, satantango)" we look from inside that noisy, busy room to see the little girl blankly looking in, behind a wall of glass; and as we already know that she's going to die early the next morning, it makes her isolation that much more piercing than the image itself communicates. The film is full of mutually-expressive conversations between shots and scenes, culminating in a climax that queasily but not fatalistically suggests that the while cycle of events is going to repeat itself, albeit with some of the principals dead, exiled, or desperately attempting to entomb themselves in their tiny little worlds, blocking all the light out by boarding up windows (the final shot of the whole movie, a brilliant parody and replacement for the traditional fade to black).

It is dense, rich, and beautiful, a visually challenging movie that uses its long takes not so much to create a reality or to draw us into the world (the blocking is much too stiff and presentational for any of this to seem remotely naturalistic), but so that every one of the cuts feels like a profound moment - a violation or a moment of emotional release, depending on the context, and sometimes both. The slow progression of the film through a relatively full narrative - there are sequences in which the conflict changes multiple times in the span of just one shot - creates a tension that makes the film spectacularly electric and even exciting to watch, a peculiar response to a film that, moment by moment, is so languorous and boring. Not as a whole, though. As a whole, this is anything but boring: it is a whirlwind tour of a whole rainbow of unhappy human emotions, presented with fluidity in the writing, the acting, and the cinematography, and it's surprisingly gripping for something so full of miserable people feeling misery. No film of this length, so fixed on human despair with only shallow, trivial attempts to stave off that despair through drunkenness and cheap sex should trigger a response at the end, "it's not over already, is it?", but that's how you can tell a masterpiece: it turns pain into art and static lives into vibrant, kinetic images, without ever cheapening its subjects in the process. It's a great film, as great as they come, and that's all there is to it.