The 49th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/12 & 10/14 & 10/20

World premiere: 26 August, 2013, Montréal World Film Festival

The question: how many shots of gorgeous cloudy skies with intensely augmented color correction that leaves them looking even more dramatic and powerful and just exactly perfect for an inspirational poster does it take before a movie starts to become extremely silly as a result? The answer: fewer than there are in The Miracle, in which a satisfying if arguably contrived infidelity drama is more or less ruined by cinematography that does everything in its power to romanticise every last minute of the film in gorgeously over-lit compositions that are literally handsome enough to pull focus from the plot, for which they are a bad fit anyway (no cinematographer was credited in the print screened in advance for critics, and so I cannot apportion blame for this where it belongs).

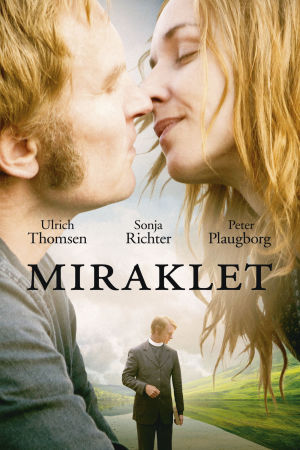

The linchpin of the romantic triangle about to erupt is Johanna (Sonja Richter), who many years ago had a promising career on the competitive ballroom dancing scene before a car accident left her without the use of her legs. A few years after that tragedy struck, she met and married a Protestant priest (Peter Plaugborg), who has since made proclamations that the miracle of her restored legs will be the proof of God's love for them and their congregation the cornerstone of his preaching; by the time we meet them, after ten years of marriage, it's hard to imagine that she ever felt particularly loved, or like anything other than a meat puppet, because that's certainly all she is now.

And things would go like this forever and ever until the sweet release of death, but somebody else dies first: Maria, the owner of a dance school where Johanna occasionally helps teach, in a limited capacity. This is a shocking, tragic event for the woman, all the more when it turns out that the new owner, Maria's long-absent son, has no interest in keeping the school open. And way more when it turns out that son is Jakob (Ulrich Thomsen), Johanna's first lover and dance partner, who she dropped when it became clear that his moderate talent was holding back her professional prospects. By this point, Jakob has become almost entirely devoid of happiness, but meeting Johanna again is all it takes to restart the spark of life in his heart and soul and primarily his crotch. The two put up a good fight, but in hardly any time at all they're sharing a bed and doing a pretty bad job of keeping it hidden from Johanna's husband, or their young son (William Lønstrup).

The only thing about this scenario that's meaningfully original is the addition of material surrounding a deeply pious man whose faith is only a mask for his authoritarian lust, his nominal affection for his wife merely a blind from which he can exert power. And that ought to be enough to tell you what "meaningfully original" even means in this context; it means that when you take two ancient clichés that aren't necessarily seen together every day of the week, and mash them up, the end result feels marginally fresher than it actually is. Still, the details of how the relationships play out are strong enough, with enough individualised insight into human behavior, that the thing feels accurate, if nothing else (the mind games involving their son that Johanna's husband plays in the last phase of the movie have an especially bracing sense of ugly authenticity, legitimate, relationship-sized cruelty that doesn't always get depicted in movies as unapologetically as it does here). Thomsen and Richter are both pretty fantastic, playing the slowly rekindled feelings between them as a slow dance (ha!) rather than just a plot-convenient burst of erotic desire.

So back to the beginning we go, to the one element which does the film in: its unmodulated visual scheme. Initially, it seems like director Simon Staho is playing a simple, obvious, but largely effective game: the times when Johanna is sad and suffocated are filmed in somewhat flat tones with plain lighting, and her moments of emotional intensity, especially when she recalls her passionate youth with Jakob (they are played here by Emma Segested Høeg and Allan Hyde, who exude charisma and chemistry, but are largely pantomiming), are represented by more flowery, lush cinematography. This doesn't end up holding true, though, and the film isn't very old before it becomes clear that nope, that's just how the filmmakers want to do things: the present and the past, moments of misery and moments of joy, shots favoring the lovers and shots favoring the cuckold, all of them are handled with painterly lighting techniques that are the very definition of "handsome", and the best we can say is that the color palette changes a little bit every now and then.

Maybe I'm picky but I just don't want my tales of emotional strangulation to be "handsome". Certainly not as unmitigated and surface-level as the handsomeness of The Miracle, an oppressively uniform movie in which all feelings are lacquered in an undifferentiated glossy coat. It's prestigious as all fuck, but only at what I'd call an unacceptable sacrifice of meaning.

6/10

World premiere: 26 August, 2013, Montréal World Film Festival

The question: how many shots of gorgeous cloudy skies with intensely augmented color correction that leaves them looking even more dramatic and powerful and just exactly perfect for an inspirational poster does it take before a movie starts to become extremely silly as a result? The answer: fewer than there are in The Miracle, in which a satisfying if arguably contrived infidelity drama is more or less ruined by cinematography that does everything in its power to romanticise every last minute of the film in gorgeously over-lit compositions that are literally handsome enough to pull focus from the plot, for which they are a bad fit anyway (no cinematographer was credited in the print screened in advance for critics, and so I cannot apportion blame for this where it belongs).

The linchpin of the romantic triangle about to erupt is Johanna (Sonja Richter), who many years ago had a promising career on the competitive ballroom dancing scene before a car accident left her without the use of her legs. A few years after that tragedy struck, she met and married a Protestant priest (Peter Plaugborg), who has since made proclamations that the miracle of her restored legs will be the proof of God's love for them and their congregation the cornerstone of his preaching; by the time we meet them, after ten years of marriage, it's hard to imagine that she ever felt particularly loved, or like anything other than a meat puppet, because that's certainly all she is now.

And things would go like this forever and ever until the sweet release of death, but somebody else dies first: Maria, the owner of a dance school where Johanna occasionally helps teach, in a limited capacity. This is a shocking, tragic event for the woman, all the more when it turns out that the new owner, Maria's long-absent son, has no interest in keeping the school open. And way more when it turns out that son is Jakob (Ulrich Thomsen), Johanna's first lover and dance partner, who she dropped when it became clear that his moderate talent was holding back her professional prospects. By this point, Jakob has become almost entirely devoid of happiness, but meeting Johanna again is all it takes to restart the spark of life in his heart and soul and primarily his crotch. The two put up a good fight, but in hardly any time at all they're sharing a bed and doing a pretty bad job of keeping it hidden from Johanna's husband, or their young son (William Lønstrup).

The only thing about this scenario that's meaningfully original is the addition of material surrounding a deeply pious man whose faith is only a mask for his authoritarian lust, his nominal affection for his wife merely a blind from which he can exert power. And that ought to be enough to tell you what "meaningfully original" even means in this context; it means that when you take two ancient clichés that aren't necessarily seen together every day of the week, and mash them up, the end result feels marginally fresher than it actually is. Still, the details of how the relationships play out are strong enough, with enough individualised insight into human behavior, that the thing feels accurate, if nothing else (the mind games involving their son that Johanna's husband plays in the last phase of the movie have an especially bracing sense of ugly authenticity, legitimate, relationship-sized cruelty that doesn't always get depicted in movies as unapologetically as it does here). Thomsen and Richter are both pretty fantastic, playing the slowly rekindled feelings between them as a slow dance (ha!) rather than just a plot-convenient burst of erotic desire.

So back to the beginning we go, to the one element which does the film in: its unmodulated visual scheme. Initially, it seems like director Simon Staho is playing a simple, obvious, but largely effective game: the times when Johanna is sad and suffocated are filmed in somewhat flat tones with plain lighting, and her moments of emotional intensity, especially when she recalls her passionate youth with Jakob (they are played here by Emma Segested Høeg and Allan Hyde, who exude charisma and chemistry, but are largely pantomiming), are represented by more flowery, lush cinematography. This doesn't end up holding true, though, and the film isn't very old before it becomes clear that nope, that's just how the filmmakers want to do things: the present and the past, moments of misery and moments of joy, shots favoring the lovers and shots favoring the cuckold, all of them are handled with painterly lighting techniques that are the very definition of "handsome", and the best we can say is that the color palette changes a little bit every now and then.

Maybe I'm picky but I just don't want my tales of emotional strangulation to be "handsome". Certainly not as unmitigated and surface-level as the handsomeness of The Miracle, an oppressively uniform movie in which all feelings are lacquered in an undifferentiated glossy coat. It's prestigious as all fuck, but only at what I'd call an unacceptable sacrifice of meaning.

6/10