Liberté

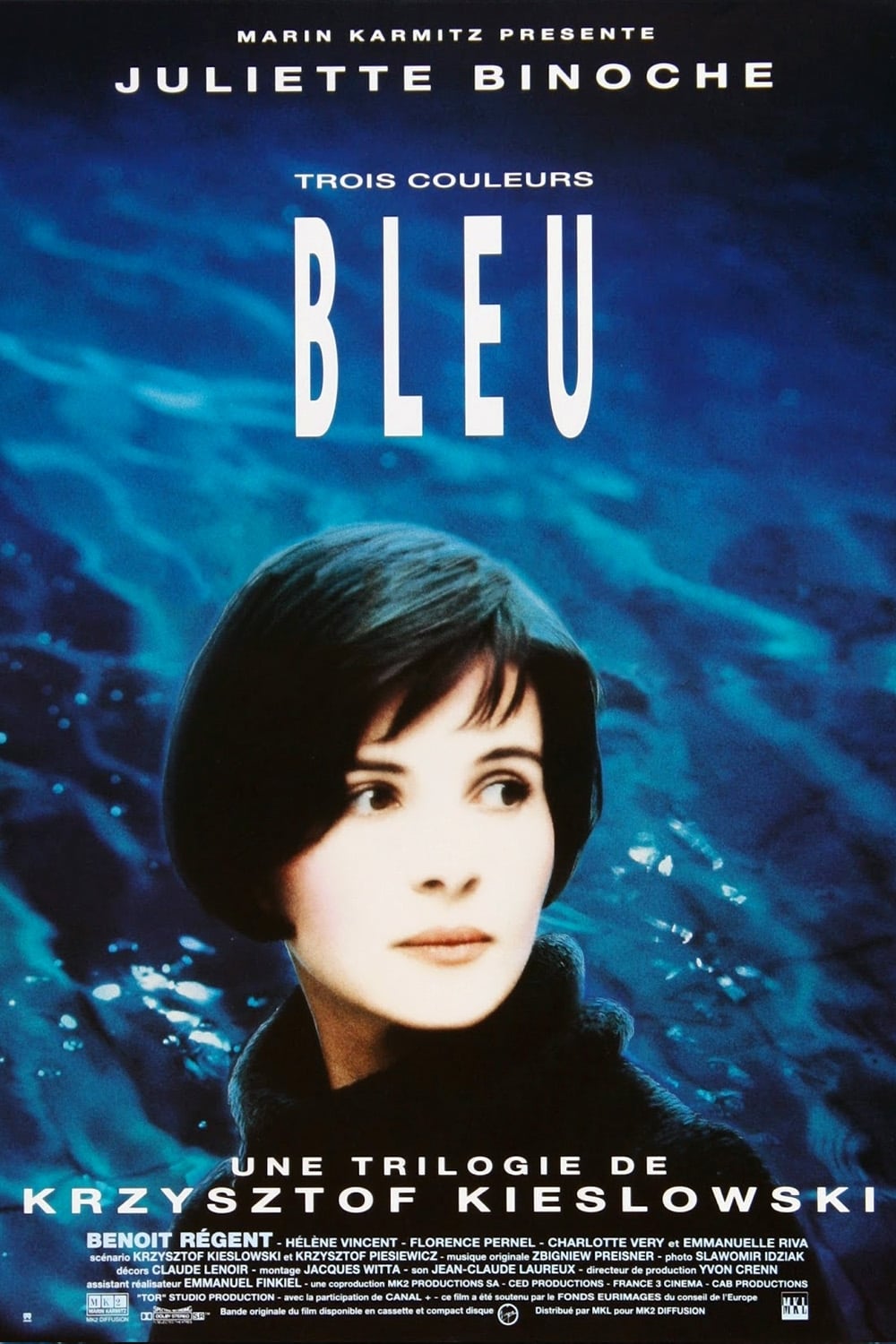

The first thing one must not do with swan song of the great Krzysztof Kieślowski, Three Colors, is to reduce it to a simple puzzle of symbolism. This is something one really must not do with a great many films, of course, but in the case of Three Colors, the temptation is unusually high, given how openly the concept of the film trilogy announces itself as eager to be read schematically. The title refers to the French flag, with the traditional reading of the blue, white, and red banner as representing the three legs of the motto of the French revolution, "liberté, égalité, fraternité", "liberty, equality, brotherhood", and those three adjectives map onto the three films, more or less. But there's more to it than that.

Even if we avoid the desire to peg Three Colors: Blue as simply, "the film about liberty", the film itself suggests an equally reductive reading. For the other thing Three Colors is clearly About, besides the revolutionary motto, is the state of Europe after the collapse of the Soviet empire, and Blue is a movie all about European unification in the early '90s. The plot, such as it is, hinges on the composition of a theme to be played in twelve countries simultaneously, an anthem for European unity, and the main character spends most of the film trying very hard and failing to have nothing to do with this theme at all. It is plainly the case, then, that Kieślowski and indispensible co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz want for their drama to be a symbolic study of the upheavals of identity facing the new Europe of 1993, but there's more to it than that, as well.

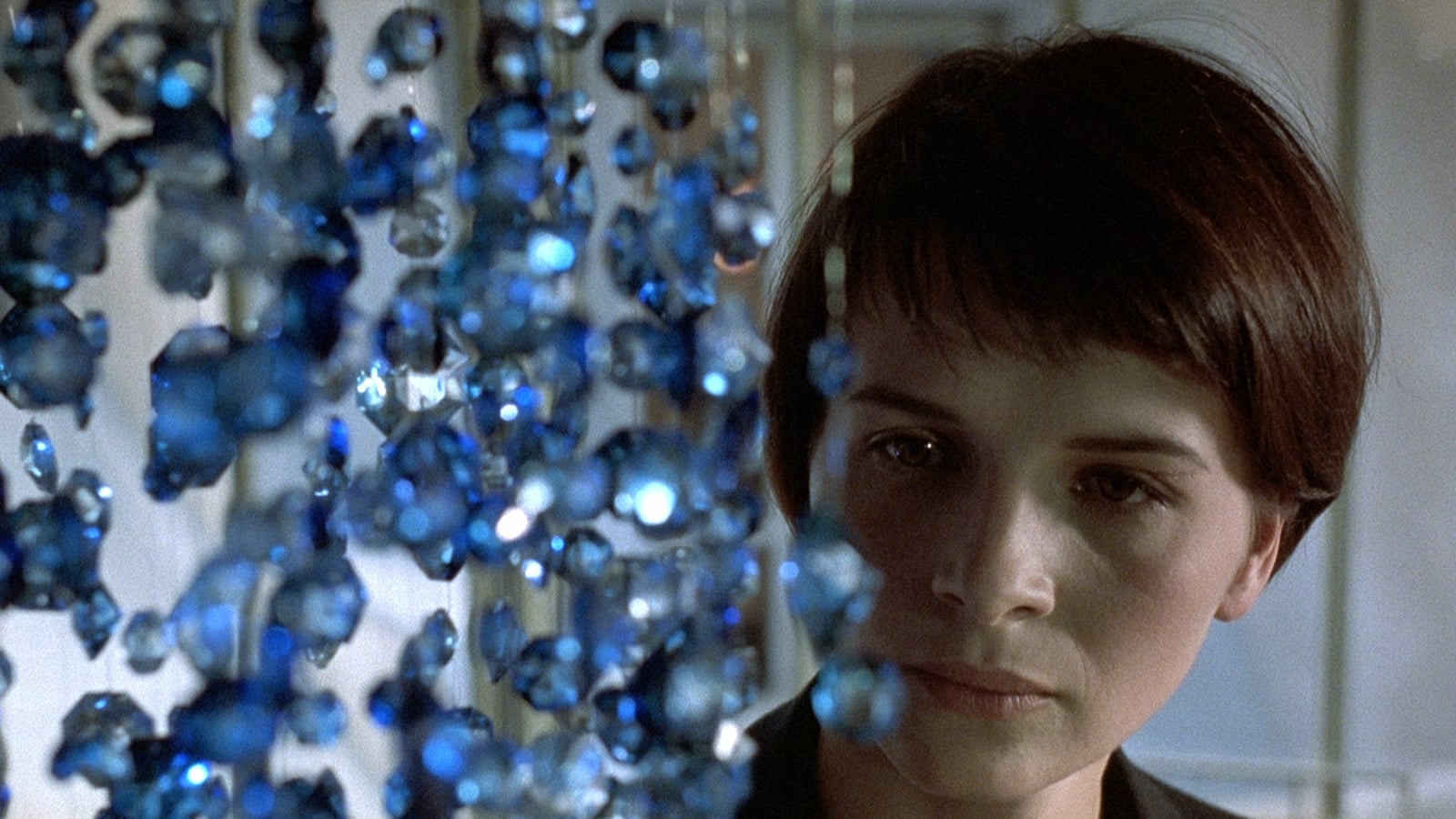

For Blue is also, simply, a great, haunting character study of Julie de Courcy (Juliette Binoche), survivor of a film-opening car accident that kills her husband, the much-beloved composer Patrice de Courcy, and their daughter Anna. This event is what gives her the liberty promised by Kieślowski and Piesiewicz's concept, which should be enough to tell you right there why reducing Three Colors to the liberté etc. framework isn't as useful as you'd maybe like it to be. What liberty means, to Julie, is the freedom from having a past or pre-established personality: the first thing she does after finding that she's too scared to commit suicide in the hospital is to sell off every scrap of property she owned or was left by Patrice, except for a single knick-knack, a chandelier made up of clear blue beads, which is hung in her new apartment.

And there's more to the film than that, too. What makes Blue brilliant - like what makes Three Colors: White and Three Colors: Red brilliant, and to be blunt about it, what makes every Kieślowski film I've seen brilliant, though especially the ones he made with Piesiewicz - is how the film seems to announce itself so plainly, with every beat of every scene clearly telegraphing what it wants to communicate thematically and narratively and spiritually (yes! spiritually! It's not really possible to discuss this director's filmography without being willing to admit that his films are among the most spiritual, though not at all religious, in cinema), the most obvious thing in the world; and yet for all that it is feels entirely straightforward in the moment of watching it, the second you try to explain it or codify it... it's simply not there any more. Blue can be a movie about liberty, about Europe in and of itself, and as metaphorically filtered through a battered woman putting herself back together, and it can be a character study to, and it can also be about, naturally enough, the color blue, and the way that human perception tends to focus on things we want to see or want specifically not to see, like if I say right now, "don't notice the blue things around you", and you look around, I can just about guarantee that blue things are all you will notice.

"They have the very rare ability to dramatize their ideas rather than just talking about them", Stanley Kubrick said of Kieślowski and Piesiewicz, and I suppose that's what I'm talking about, really. Blue is an intuitive film: it could not be any less schematic if it tried, no matter how much it feels, in describing it, like it's nothing but one schema on top of another.

Anyway, let's return to Julie where we left her, attempting to entirely erase the memory of Julie de Courcy, taking back her maiden name Vignon and refusing to speak in public or private about the "Song for the Unification of Europe" that Patrice left unfinished at his death (and which Julie tries to leave even more unfinished, throwing what she mistakenly believes to be the only copy into a garbage truck). View this only in the outline, you might be so bold as to call it feminism, but there's nothing like that at all - Julie's actions are not affirmative and thus feminist, but negative: this is a film about a woman trying to eradicate feelings, inner life, human connection. Binoche is magnificent in the role, giving not merely the best performance of her career but one of the best ever put to film, crafting a stone-faced edifice that looks like uncaring, unfeeling, inexpressiveness, but Binoche carefully puts just enough of a crack in that perfectly smooth, unknowable face in the moments where she thinks nobody is watching, or when she's caught off guard, that we in the film audience understand that something is going on at a deep level in there. By all means, Julie exits the movie as someone we only barely understand, but not because she is vague. It's because at the end of the movie, she finally really is able to use her newfound freedom to reinvent herself - not as a reactive, inhuman figure of detachment and insulation, but as a newborn, full of all possibilities. Y'know, like a newly unified Europe, but I really did promise myself that I wasn't going to spend too much time on the politically metaphorical elements of the film.

The all-encompassing question of what's going on in Julie's mind in the final shot of the film is thus left quite unanswerable, much like the big narrative ellipsis as to whether Julie, and not Patrice, was actually responsible for the composition of "Song for the Unification of Europe"; but for a film that does its absolute damnedest to leave nothing resolved - it is the most elliptical of the Three Colors films, almost as deliberately vague as what I tend to think of as the Three Colors apprentice film, The Double Life of Véronique - Blue reveals quite a lot. It just doesn't do it in the context of narrative, but of character psychology and character emotion, things that are expressed through Binoche's performance, as well as the filmmakers' at times somewhat pushy formalism. Blue is an especially visual and aural experience even by the standards of a directorial career that's rather heavy on visual communication, as Kubrick pointed out. There is, for example, the repeated trick (it is used four times, always with profound significance) of fading to black and letting the score, composed by the incomparable Zbigniew Preisner on Patrice and Julie's behalf soar up and belt us right in the face. It's not a hugely sophisticated trick - it represents the four moments when Julie is most taken aback and forced to confront her emotions without a chance to secure herself in a layer of protective detachment - but it doesn't have to be sophisticated when it works so incredibly well. And it does that, oh so much.

The title of the film itself points us to what's going on in the visuals, the last of three collaborations between Kieślowski and Sławomir Idziak, who goes right on ahead and makes the entire movie feel blue - a chilly color in this rendering, rather than a depressive one, but the film doesn't rely on what the audience thinks of the color, anyway. What matter is what Julie thinks of the color, and this is communicated to us implicitly, silently: it is the color she associates with her dead family, and the color she attempts to reclaim (explicitly in the form of that blue chandelier, the only object we see her attack, and the only object she takes with her). It is the color she sees or feels, if you can be said to feel a color, in the same moments that she hears the Song echoing in her head (the movie neatly presents its non-diegetic score as entirely contained in the protagonist's mind), when she is least able to banish feeling and identity and humanity. In the end, when she actively decides to rejoin the human race, she is wearing - barely visible, you can only see the cuffs - a blue shirt, and after both fighting and attempting to dominate the color, she finally gives into it.

Blue, the color, thus represents liberty and the renunciation of liberty, at least as it's defined here, as the freedom from obligation but also, necessarily, freedom from connectivity. But anti- things are common in Three Colors, the films of which are commonly described as anti-tragedy, anti-comedy, and anti-romance, respectively. Anti-tragedy certainly fits Blue: it is theoretically about a sad event that wounds a woman, but the entire action of the film lies in Julie's act of rising out of tragedy and misery (and what is the stone-faced attempt to squash all misery by feeling nothing at all, but a complete and unconditional surrender to being miserable?), using bereavement to refocus herself. The plot describes letting go and facing forward, building new things and not harboring pain (dramatised as Julie throwing herself into the act of composition, while giving a home to her husband's mistress, the person she hates most). It is about the act of deciding what you want to write on a blank slate: the first time we see Binoche's face, is immediately after learning that Julie is now widowed; she is introduced to us as a person who has just been untied from her past self. Blue is, then, the story of how to become a new, better, more whole self, whether as a single person or an entire continent, and learning how to prevent past trauma from infecting the present. There is nothing less tragic than that.

Reviews in this series

Three Colors: Blue (Kieślowski, 1993)

Three Colors: White (Kieślowski, 1994)

Three Colors: Red (Kieślowski, 1994)

Even if we avoid the desire to peg Three Colors: Blue as simply, "the film about liberty", the film itself suggests an equally reductive reading. For the other thing Three Colors is clearly About, besides the revolutionary motto, is the state of Europe after the collapse of the Soviet empire, and Blue is a movie all about European unification in the early '90s. The plot, such as it is, hinges on the composition of a theme to be played in twelve countries simultaneously, an anthem for European unity, and the main character spends most of the film trying very hard and failing to have nothing to do with this theme at all. It is plainly the case, then, that Kieślowski and indispensible co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz want for their drama to be a symbolic study of the upheavals of identity facing the new Europe of 1993, but there's more to it than that, as well.

For Blue is also, simply, a great, haunting character study of Julie de Courcy (Juliette Binoche), survivor of a film-opening car accident that kills her husband, the much-beloved composer Patrice de Courcy, and their daughter Anna. This event is what gives her the liberty promised by Kieślowski and Piesiewicz's concept, which should be enough to tell you right there why reducing Three Colors to the liberté etc. framework isn't as useful as you'd maybe like it to be. What liberty means, to Julie, is the freedom from having a past or pre-established personality: the first thing she does after finding that she's too scared to commit suicide in the hospital is to sell off every scrap of property she owned or was left by Patrice, except for a single knick-knack, a chandelier made up of clear blue beads, which is hung in her new apartment.

And there's more to the film than that, too. What makes Blue brilliant - like what makes Three Colors: White and Three Colors: Red brilliant, and to be blunt about it, what makes every Kieślowski film I've seen brilliant, though especially the ones he made with Piesiewicz - is how the film seems to announce itself so plainly, with every beat of every scene clearly telegraphing what it wants to communicate thematically and narratively and spiritually (yes! spiritually! It's not really possible to discuss this director's filmography without being willing to admit that his films are among the most spiritual, though not at all religious, in cinema), the most obvious thing in the world; and yet for all that it is feels entirely straightforward in the moment of watching it, the second you try to explain it or codify it... it's simply not there any more. Blue can be a movie about liberty, about Europe in and of itself, and as metaphorically filtered through a battered woman putting herself back together, and it can be a character study to, and it can also be about, naturally enough, the color blue, and the way that human perception tends to focus on things we want to see or want specifically not to see, like if I say right now, "don't notice the blue things around you", and you look around, I can just about guarantee that blue things are all you will notice.

"They have the very rare ability to dramatize their ideas rather than just talking about them", Stanley Kubrick said of Kieślowski and Piesiewicz, and I suppose that's what I'm talking about, really. Blue is an intuitive film: it could not be any less schematic if it tried, no matter how much it feels, in describing it, like it's nothing but one schema on top of another.

Anyway, let's return to Julie where we left her, attempting to entirely erase the memory of Julie de Courcy, taking back her maiden name Vignon and refusing to speak in public or private about the "Song for the Unification of Europe" that Patrice left unfinished at his death (and which Julie tries to leave even more unfinished, throwing what she mistakenly believes to be the only copy into a garbage truck). View this only in the outline, you might be so bold as to call it feminism, but there's nothing like that at all - Julie's actions are not affirmative and thus feminist, but negative: this is a film about a woman trying to eradicate feelings, inner life, human connection. Binoche is magnificent in the role, giving not merely the best performance of her career but one of the best ever put to film, crafting a stone-faced edifice that looks like uncaring, unfeeling, inexpressiveness, but Binoche carefully puts just enough of a crack in that perfectly smooth, unknowable face in the moments where she thinks nobody is watching, or when she's caught off guard, that we in the film audience understand that something is going on at a deep level in there. By all means, Julie exits the movie as someone we only barely understand, but not because she is vague. It's because at the end of the movie, she finally really is able to use her newfound freedom to reinvent herself - not as a reactive, inhuman figure of detachment and insulation, but as a newborn, full of all possibilities. Y'know, like a newly unified Europe, but I really did promise myself that I wasn't going to spend too much time on the politically metaphorical elements of the film.

The all-encompassing question of what's going on in Julie's mind in the final shot of the film is thus left quite unanswerable, much like the big narrative ellipsis as to whether Julie, and not Patrice, was actually responsible for the composition of "Song for the Unification of Europe"; but for a film that does its absolute damnedest to leave nothing resolved - it is the most elliptical of the Three Colors films, almost as deliberately vague as what I tend to think of as the Three Colors apprentice film, The Double Life of Véronique - Blue reveals quite a lot. It just doesn't do it in the context of narrative, but of character psychology and character emotion, things that are expressed through Binoche's performance, as well as the filmmakers' at times somewhat pushy formalism. Blue is an especially visual and aural experience even by the standards of a directorial career that's rather heavy on visual communication, as Kubrick pointed out. There is, for example, the repeated trick (it is used four times, always with profound significance) of fading to black and letting the score, composed by the incomparable Zbigniew Preisner on Patrice and Julie's behalf soar up and belt us right in the face. It's not a hugely sophisticated trick - it represents the four moments when Julie is most taken aback and forced to confront her emotions without a chance to secure herself in a layer of protective detachment - but it doesn't have to be sophisticated when it works so incredibly well. And it does that, oh so much.

The title of the film itself points us to what's going on in the visuals, the last of three collaborations between Kieślowski and Sławomir Idziak, who goes right on ahead and makes the entire movie feel blue - a chilly color in this rendering, rather than a depressive one, but the film doesn't rely on what the audience thinks of the color, anyway. What matter is what Julie thinks of the color, and this is communicated to us implicitly, silently: it is the color she associates with her dead family, and the color she attempts to reclaim (explicitly in the form of that blue chandelier, the only object we see her attack, and the only object she takes with her). It is the color she sees or feels, if you can be said to feel a color, in the same moments that she hears the Song echoing in her head (the movie neatly presents its non-diegetic score as entirely contained in the protagonist's mind), when she is least able to banish feeling and identity and humanity. In the end, when she actively decides to rejoin the human race, she is wearing - barely visible, you can only see the cuffs - a blue shirt, and after both fighting and attempting to dominate the color, she finally gives into it.

Blue, the color, thus represents liberty and the renunciation of liberty, at least as it's defined here, as the freedom from obligation but also, necessarily, freedom from connectivity. But anti- things are common in Three Colors, the films of which are commonly described as anti-tragedy, anti-comedy, and anti-romance, respectively. Anti-tragedy certainly fits Blue: it is theoretically about a sad event that wounds a woman, but the entire action of the film lies in Julie's act of rising out of tragedy and misery (and what is the stone-faced attempt to squash all misery by feeling nothing at all, but a complete and unconditional surrender to being miserable?), using bereavement to refocus herself. The plot describes letting go and facing forward, building new things and not harboring pain (dramatised as Julie throwing herself into the act of composition, while giving a home to her husband's mistress, the person she hates most). It is about the act of deciding what you want to write on a blank slate: the first time we see Binoche's face, is immediately after learning that Julie is now widowed; she is introduced to us as a person who has just been untied from her past self. Blue is, then, the story of how to become a new, better, more whole self, whether as a single person or an entire continent, and learning how to prevent past trauma from infecting the present. There is nothing less tragic than that.

Reviews in this series

Three Colors: Blue (Kieślowski, 1993)

Three Colors: White (Kieślowski, 1994)

Three Colors: Red (Kieślowski, 1994)