The films of Tony Scott

Nihilistic violence, caustic misogyny, soullessly ironic humor: The Last Boy Scout should feel indistinguishable from all the other early-'90s action movies on the same post-Die Hard model, yet it is vastly more fascinating than any of them. Not, to be sure, for reasons that are entirely to its credit. At its worst, the film is a savage, nasty thing, too intoxicated with it's cooler-than-thou refusal to observe any flicker of human decency in its characters or the world at large for it to even be much fun on the level of "dude, that was awesome the way he killed that guy". And it is not afraid to tarry in the worst places. What it has that none of the other equally brutally cool movies of its genre and generation have, is a level of tension among the members of its creative team that leaves it more complicated and taut than its most obvious surface level details would suggest. One is constantly aware while watching that the film is fighting with itself, trying both to be the best version of itself and to be absolutely anything else. The result is undeniably messy, but captivatingly so.

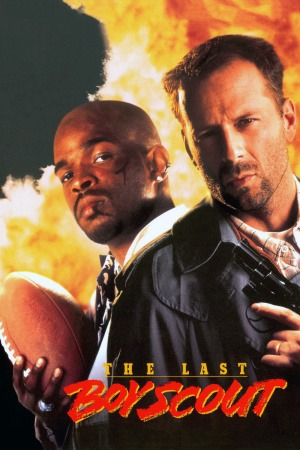

The Last Boy Scout is the child of four fathers, all of them playing a key role in this saga. The first is writer Shane Black, who received a record sum of $1.75 million for a spec script (the record stood for all of two months, before Joe Eszterhas sold Basic Instinct for $2 million), and for whom this stood as the moment that the wave broke on his career: he spent the rest of the '90s chasing the superstardom of his white-hot youth, and didn't really return to the A-list until 2013's Iron Man 3. The others are producer Joel Silver, whose Silver Pictures was responsible for many of the era's flashiest, most hollow adventures in stylised, consequence-free action (he'd already worked with Black on the iconic, career-making Lethal Weapon); and star Bruce Willis, who'd worked with Silver on Die Hard and was at that very delicate point in his career where he still had enough lingering clout from his late-'80s run of smash hits that he could throw his weight around, and enough recent bombs that he knew how badly he needed a starring role that showed him off to best effect. The fourth was director Tony Scott, who alone among the four had never worked with any of the others and never worked with any of them again, and that's certainly not an accident. For it is known that at least three of these men found The Last Boy Scout to be a uniquely unpleasant experience in their careers: Black watched as the producer and star turned his script into something frequently unrecognisable, Scott was obliged to make a movie with a plot and tone that he didn't care for in the slightest, Silver had to constantly but heads with a director who made his unhappiness well-known.

Sometimes, that kind of free-for-all animosity turns into creative gold; sometimes it makes everything seem strained and tense and unpleasant. The Last Boy Scout comes much closer to the latter than the former, but there's no doubt that the movie as it exists is far more excitingly fraught than it would have been if Scott, for one, had more of a friendly relationship with Silver and Willis. It's not subverting itself, and I don't think I'd accuse anyone of trying to subvert it: the one thing that none of the four creators seems especially uncomfortable with are the violence-fetishisation and the ugly sexism that are the film's worst problems, and can be found pretty easily in any of their respective filmographies. But Scott's The Last Boy Scout is far more self-lacerating than Silver's The Last Boy Scout, and the difference there is terrifically interesting.

The content of the film is straightforward enough: an exceptionally low-rent Los Angeles private investigator, Joe Hallenbeck (Willis) is thrown a bone by his buddy and colleague, Mike Matthews (Bruce McGill) to act as bodyguard for a stripper named Cory (Halle Berry). The same morning that he takes the job, Joe finds his wife, Sarah (Chelsea Field) is having an affair with Mike, and Mike ends up on the wrong side of a car bomb while trying to get out as quickly as possible. This, then, is the first hint that Something Is Up, and the clues only get more and more dangerous after Cory ends up dead, with Joe and her boyfriend, ex-NFL quarterback Jimmy Dix (Damon Wayans), teaming up to figure out what the hell is going on. It's pretty classic film noir stuff, down to the bloodcurdling cynicism of the lead detective, a depressive sort who is investigating the crime almost solely because he has nothing else to do: certainly not hang around with his shrill monster of a wife and hateful 13-year-old daughter (Danielle Harris). Things are revealed over the course of the movie, including not just the political gambit that has triggered all these deaths, but also Joe's history as a heroic Secret Service agent, and that's when we find out that this miserable bastared is the last Boy Scout of the title, a man who would be upright and noble if only everything else in the world wasn't pulling him down. Which is probably the most nihilistic part of the whole thing.

Coming as it does from the mind of Black, and co-scenarist Greg Hicks, it's no surprise that this takes the form of a buddy-cop comedy, with Willis and Wayans exchanging quips at rapid fire pace. Though often, in practice, this ends up taking the form of Willis shooting quips at Wayans, given that the star was not, by and large, known for his work as co-lead (my back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that the first successful "buddy" film starring Willis was Die Hard with a Vengeance, four years later). And this is the first place where The Last Boy Scout suddenly becomes a weird movie, not for good or ill, though it's certainly more memorable as a result: Bruce Willis in 1991 was not remotely Mel Gibson in 1987, and playing Gibson's Lethal Weapon character as John McClane from the Die Hards was a poor marriage. It certainly doesn't help that Willis tends to undersell the typically Blackian lines, playing them as angry sarcasm delivered with methodical viciousness more than quick-witted jabs; nor does it do the movie much good that Scott's direction leaves absolutely no room for comic expansion anyway.

In fact, Scott's direction tends on the whole to make The Last Boy Scout considerable darker than it needs to be; not a single one of the Silver Pictures films of that generation stay in their moments of violence for so long. The short version is that Scott was simply better suited to making movies with Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, whose sense of what an action film should be was very much about sizzle and over-the-top glamor and theatricality, whereas Silver's movies tend to involve a much harder edge of brutality with urban trimmings. The Tony Scott who came up through TV commercials was ideally suited to making Simpson/Bruckheimer productions, which are all about valorising mechanical objects: Air Force fighters, racing cars, Navy submarines. He was not nearly as well suited to making Silver Pictures, with their fixation on violence and action, and whether he deliberately overcompensated or if it's exactly what made him so unhappy to be working with the producer, The Last Boy Scout ends up being almost comically under-emphasised: the character moments are all low-key, purring with subdued tension rather than overt activity; there are so many dark interiors, lit by Ward Russell to resemble a serious of mausoleums, with dusky light pouring through windows in shafts.

The only points where the directing comes alive are at the very beginning, where a hilarious parody of the opening of TV football segues into an irresistibly off-kilter murder-suicide on the football field, and the movie promises to be far more cryptic and deliberately freakish than remotely proves to be the case; and at the very end, in the film's one true action setpiece, where Scott's instincts to heighten the action through exaggeration fits with Silver's desires (it is a weirdly action-light movie, considering how importantly action figures in both filmmakers' filmographies). Which isn't to say that the rest of the movie is bad; the degree to which Scott keeps undercutting the film gives it far more personality than it would have had with a director who was more interested in making a generic Bruce Willis movie, even if that personality is defiantly anti-coherent. The sad part is that the real loser in all of this is Black, who I think to be my favorite of all the people involved in making the film, and who got to see his script butchered first by the producer and then what was left throttled by the director.

And there's also the film's irredeemable ugliness: the total valuelessness of any of the females in the piece is a major problem, particularly given the way that the happy ending plays off Joe's passive-aggressive taunting of his now-humbled wife as a healthy restoration of their relationship. And like virtually all Joel Silver productions in the wake of Die Hard (whose success apparently gave the producer an inflated sense of self-worth, and resulted in him never making anything remotely as good ever again), it's genuinely bloodthirsty without the sense of whimsy that makes the best '80s action movies seem fun rather than mean (a problem endemic to early-'90s action cinema, "fixed" when Tarantino showed everybody how to do post-modern action). These are problems which authorial infighting can neither fix nor alleviate. But in general, the sins of The Last Boy Scout are common to literally dozens of other movies, and its strengths are replicated nowhere else; it's a very problematic movie, no doubt, but it's frequently the biggest problems that are the most interesting things to study.

The Last Boy Scout is the child of four fathers, all of them playing a key role in this saga. The first is writer Shane Black, who received a record sum of $1.75 million for a spec script (the record stood for all of two months, before Joe Eszterhas sold Basic Instinct for $2 million), and for whom this stood as the moment that the wave broke on his career: he spent the rest of the '90s chasing the superstardom of his white-hot youth, and didn't really return to the A-list until 2013's Iron Man 3. The others are producer Joel Silver, whose Silver Pictures was responsible for many of the era's flashiest, most hollow adventures in stylised, consequence-free action (he'd already worked with Black on the iconic, career-making Lethal Weapon); and star Bruce Willis, who'd worked with Silver on Die Hard and was at that very delicate point in his career where he still had enough lingering clout from his late-'80s run of smash hits that he could throw his weight around, and enough recent bombs that he knew how badly he needed a starring role that showed him off to best effect. The fourth was director Tony Scott, who alone among the four had never worked with any of the others and never worked with any of them again, and that's certainly not an accident. For it is known that at least three of these men found The Last Boy Scout to be a uniquely unpleasant experience in their careers: Black watched as the producer and star turned his script into something frequently unrecognisable, Scott was obliged to make a movie with a plot and tone that he didn't care for in the slightest, Silver had to constantly but heads with a director who made his unhappiness well-known.

Sometimes, that kind of free-for-all animosity turns into creative gold; sometimes it makes everything seem strained and tense and unpleasant. The Last Boy Scout comes much closer to the latter than the former, but there's no doubt that the movie as it exists is far more excitingly fraught than it would have been if Scott, for one, had more of a friendly relationship with Silver and Willis. It's not subverting itself, and I don't think I'd accuse anyone of trying to subvert it: the one thing that none of the four creators seems especially uncomfortable with are the violence-fetishisation and the ugly sexism that are the film's worst problems, and can be found pretty easily in any of their respective filmographies. But Scott's The Last Boy Scout is far more self-lacerating than Silver's The Last Boy Scout, and the difference there is terrifically interesting.

The content of the film is straightforward enough: an exceptionally low-rent Los Angeles private investigator, Joe Hallenbeck (Willis) is thrown a bone by his buddy and colleague, Mike Matthews (Bruce McGill) to act as bodyguard for a stripper named Cory (Halle Berry). The same morning that he takes the job, Joe finds his wife, Sarah (Chelsea Field) is having an affair with Mike, and Mike ends up on the wrong side of a car bomb while trying to get out as quickly as possible. This, then, is the first hint that Something Is Up, and the clues only get more and more dangerous after Cory ends up dead, with Joe and her boyfriend, ex-NFL quarterback Jimmy Dix (Damon Wayans), teaming up to figure out what the hell is going on. It's pretty classic film noir stuff, down to the bloodcurdling cynicism of the lead detective, a depressive sort who is investigating the crime almost solely because he has nothing else to do: certainly not hang around with his shrill monster of a wife and hateful 13-year-old daughter (Danielle Harris). Things are revealed over the course of the movie, including not just the political gambit that has triggered all these deaths, but also Joe's history as a heroic Secret Service agent, and that's when we find out that this miserable bastared is the last Boy Scout of the title, a man who would be upright and noble if only everything else in the world wasn't pulling him down. Which is probably the most nihilistic part of the whole thing.

Coming as it does from the mind of Black, and co-scenarist Greg Hicks, it's no surprise that this takes the form of a buddy-cop comedy, with Willis and Wayans exchanging quips at rapid fire pace. Though often, in practice, this ends up taking the form of Willis shooting quips at Wayans, given that the star was not, by and large, known for his work as co-lead (my back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that the first successful "buddy" film starring Willis was Die Hard with a Vengeance, four years later). And this is the first place where The Last Boy Scout suddenly becomes a weird movie, not for good or ill, though it's certainly more memorable as a result: Bruce Willis in 1991 was not remotely Mel Gibson in 1987, and playing Gibson's Lethal Weapon character as John McClane from the Die Hards was a poor marriage. It certainly doesn't help that Willis tends to undersell the typically Blackian lines, playing them as angry sarcasm delivered with methodical viciousness more than quick-witted jabs; nor does it do the movie much good that Scott's direction leaves absolutely no room for comic expansion anyway.

In fact, Scott's direction tends on the whole to make The Last Boy Scout considerable darker than it needs to be; not a single one of the Silver Pictures films of that generation stay in their moments of violence for so long. The short version is that Scott was simply better suited to making movies with Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, whose sense of what an action film should be was very much about sizzle and over-the-top glamor and theatricality, whereas Silver's movies tend to involve a much harder edge of brutality with urban trimmings. The Tony Scott who came up through TV commercials was ideally suited to making Simpson/Bruckheimer productions, which are all about valorising mechanical objects: Air Force fighters, racing cars, Navy submarines. He was not nearly as well suited to making Silver Pictures, with their fixation on violence and action, and whether he deliberately overcompensated or if it's exactly what made him so unhappy to be working with the producer, The Last Boy Scout ends up being almost comically under-emphasised: the character moments are all low-key, purring with subdued tension rather than overt activity; there are so many dark interiors, lit by Ward Russell to resemble a serious of mausoleums, with dusky light pouring through windows in shafts.

The only points where the directing comes alive are at the very beginning, where a hilarious parody of the opening of TV football segues into an irresistibly off-kilter murder-suicide on the football field, and the movie promises to be far more cryptic and deliberately freakish than remotely proves to be the case; and at the very end, in the film's one true action setpiece, where Scott's instincts to heighten the action through exaggeration fits with Silver's desires (it is a weirdly action-light movie, considering how importantly action figures in both filmmakers' filmographies). Which isn't to say that the rest of the movie is bad; the degree to which Scott keeps undercutting the film gives it far more personality than it would have had with a director who was more interested in making a generic Bruce Willis movie, even if that personality is defiantly anti-coherent. The sad part is that the real loser in all of this is Black, who I think to be my favorite of all the people involved in making the film, and who got to see his script butchered first by the producer and then what was left throttled by the director.

And there's also the film's irredeemable ugliness: the total valuelessness of any of the females in the piece is a major problem, particularly given the way that the happy ending plays off Joe's passive-aggressive taunting of his now-humbled wife as a healthy restoration of their relationship. And like virtually all Joel Silver productions in the wake of Die Hard (whose success apparently gave the producer an inflated sense of self-worth, and resulted in him never making anything remotely as good ever again), it's genuinely bloodthirsty without the sense of whimsy that makes the best '80s action movies seem fun rather than mean (a problem endemic to early-'90s action cinema, "fixed" when Tarantino showed everybody how to do post-modern action). These are problems which authorial infighting can neither fix nor alleviate. But in general, the sins of The Last Boy Scout are common to literally dozens of other movies, and its strengths are replicated nowhere else; it's a very problematic movie, no doubt, but it's frequently the biggest problems that are the most interesting things to study.

Categories: action, mysteries, shane black, thrillers, tony scott