Blockbuster History: Battle bots

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the genealogy of Pacific Rim rather obviously includes the kaiju eiga, Japan's legendary giant monster movies spanning the last half-century and more. But you don't need to go to East Asia to find stories of men operating giant robots to fight their wars in what look uncommonly like wrestling matches.

Robot Jox is the movie you think it is. Unless you think it's a film about athletic supporters being worn by robots, in which case congratulations on finding a fetish that even the internet doesn't want to have anything to do with. In fact, it is a movie about men pilot robots and fighting each other while inside of them. The "x" in the title is enough to give us a good idea that it's probably a cheapie from the '80s, and that may already be enough to key us in to the fact that it's a Top Gun clone. It's also not hard to jump from there to the post-apocalyptic future setting (robots = sci-fi, and cheap sci-fi in the '80s = post-apocalypse). Everything else is secondary, or even tertiary.

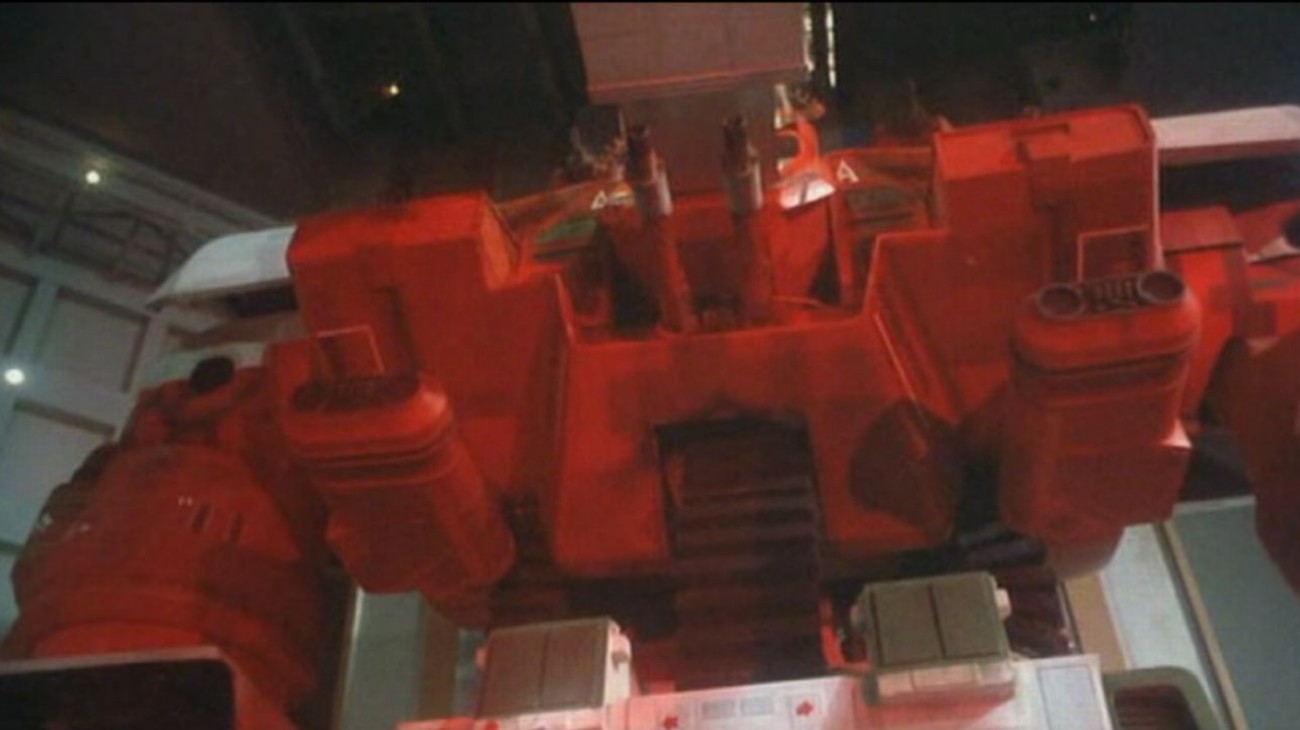

That said, it's a pretty cheap movie - legendarily prolific executive producer Charles Band was at no point in the business of making anything but cheap movies - and even though it was the most expensive film in the history of Empire Pictures (one of the many, many companies Band started over the years), expensive enough to bankrupt the company, it still only had so much money to spend on David Allen's lovingly homey stop motion robot fighters, and most of that was held off until the climactic battle scene. Which means, of course, that even at a fleet 85 minutes, Robot Jox needs a lot of stuff besides robot jockeying to function as more than a plotless short. And here is what that stuff consists of:

50 years after the inevitable nuclear Armageddon, the United States and its allies (now called the Market) and the USSR and its allies (now called the Confederation) have outlawed war. All territorial disputes are achieved in one-on-one battle between the great hundred-foot robots that make up the entirety of the two nations' armies, with the one country basically announcing, "I want to take over [Alaska]," and the other territory sending their best robot jock to defend it. It's Risk, basically, perhaps owing to a cultural memory that lingered after all board games were destroyed in the fires of nuclear death.

The two great robot jocks of this particular future are Achilles of the Market (Gary Graham) and Alexander of the Confederation (Paul Koslo), the former of whom is just one bout away from being done with his contract with the Market government, the latter of whom is a bloodthirsty psychopath, what with being a Russian analogue in a late-'80s cheapie action film and all. They meet to contest Alaska - which would be the first loss of a central Market territory in years - and end in a draw when Alexander is able to defend Achilles's top-secret new weaponry almost like he'd been tipped off about it. The international organisation responsible for arbitrating such things declares a rematch one week in the future, with Achilles insisting that he's earned his retirement, while his strategist Tex Conway (Michael Alldredge) and weapons designer Matsumoto (Danny Kamekona) hunt for the spy. When a genetically engineered soldier named Athena (Anne-Marie Johnson) is tapped to fight Alexander - the first woman and the first "tubie", as the new generation of lab-created humans are derisively called, to fight in robot combat - Achilles prepares to fight the battle he'd so assiduously dodged out of; for by this point, he has fallen in love with Athena, she being the sole named female in the film and all.

Given its genealogy in the hands of Charles Band and his father, producer Albert Band, Robot Jox looks unbelievably posh (that is to say: it merely looks like a very low-budget indie, not a dysfunctionally low-budget indie), and the central concept is sound enough. But it is, despite its accrual of an appreciative cult in later years, pretty fucking awful, and the reason couldn't be more obvious, since the filmmakers have owned up to it: writer Joe Haldeman wanted to make a geopolitically serious consideration of how wars by proxy might look in the future, and director/scenarist Stuart Gordon wanted to make a junky action film for kids. This tension never resolves itself; never even comes close to it. The Top Gun-esque romance between Achilles and Athena takes central stage for much too long to justify the silly tone Gordon brings to every other moment of the whole picture, and the remnants of the harder-tinged sci-fi that the director wanted to avoid making cling to the project, sad and forlorn and conspicuous in their lack of follow-through.

Of course, the single dumbest element of the film can't be blamed on anything but bad luck: Robot Jox was started in 1987, with delays in post-production owing largely to the fact that the production company had ceased to exist. An eventual 1989 release date flew by (though it did have its premiere in that year) without the film seeing actual release, as did an April, 1990 date, and eventually the film bowed in November, 1990, by which point the Soviet Union had disintegrated, leaving the film's loud and proud Cold War scenario looking a bit ridiculous, even with the fig leaf of "the Confederation" hiding things.

But just because we can forgive the film that one unusually large gaffe, that doesn't mean there's not plenty else to pick on, with the biggest problem coming in the form of its characters and the actors playing them: caught between Gordon's desire to make a kiddie matinee and the script's attempt to do something more adult, Graham and Johnson - neither of them meaningfully great actors to begin with - ended up completely lost, giving the most feeble and thinly-inhabited performances imaginable, and leaving the figures of Achilles and Athena totally uninteresting and unlikable, with their plot-driving romance thoroughly uncompelling. Koslo acquits himself better; he had a one-note villain to play and his atrocious cartoon Russkie (with an accent that sounds far more like Count Dracula; his delivery of the word "blood" in one scene seals the deal) at least feels like it has committed to a tone of relentlessly B-movie cheese. We can argue about whether or not this is an appealing tone - myself, I find it rather enervating after just a little bit - but at least it feels part of the movie around it.

The whole thing is really very daft: giant robots as war proxies is already a bit of a goofy concept that needs to be treated with a certain lightness, but Robot Jox errs on the side of being inept and inane, which I take to be a function of Gordon, whose best work (like the terrific Re-Animator) thrives on playfully excessive violence, and whose strengths are in no way suited to making something family-friendly without it feeling forced and insincere. It comes alive only during the fight scenes, which are unmistakably cheap and look 15 years out of date for a 1989 film, but have a DIY charm about them, and the robot design is stellar, whatever else is the case. The final scene is pretty great, anyway, though it comes at the end of a long slog of imbalanced melodrama and political thriller mechanics that nothing in the film is prepared to grapple with.

All in all, a piece of shit, pretty much: but it's such fun to watch! I was lucky enough to first see the movie at the 24-hour bad movie marathon B-Fest, certainly the best place in the world to watch such a movie, where its manifold failures of art and storytelling could be appreciated for their gung-ho hokiness rather than dismissed outright. That experience might still influence my viewing of the movie; I can't really say. But it seems to me that even on its own merits, Robot Jox is lovably dopey and its flippant, cartoon tone is an asset in terms of enjoying it, even as it's probably the biggest reason that the film bombs so hard at creating a legitimate reality. It's quintessentially So Bad It's Good, with just enough conviction that it's really easy to like, even while there's absolutely no chance in hell that you could ever respect it.

Robot Jox is the movie you think it is. Unless you think it's a film about athletic supporters being worn by robots, in which case congratulations on finding a fetish that even the internet doesn't want to have anything to do with. In fact, it is a movie about men pilot robots and fighting each other while inside of them. The "x" in the title is enough to give us a good idea that it's probably a cheapie from the '80s, and that may already be enough to key us in to the fact that it's a Top Gun clone. It's also not hard to jump from there to the post-apocalyptic future setting (robots = sci-fi, and cheap sci-fi in the '80s = post-apocalypse). Everything else is secondary, or even tertiary.

That said, it's a pretty cheap movie - legendarily prolific executive producer Charles Band was at no point in the business of making anything but cheap movies - and even though it was the most expensive film in the history of Empire Pictures (one of the many, many companies Band started over the years), expensive enough to bankrupt the company, it still only had so much money to spend on David Allen's lovingly homey stop motion robot fighters, and most of that was held off until the climactic battle scene. Which means, of course, that even at a fleet 85 minutes, Robot Jox needs a lot of stuff besides robot jockeying to function as more than a plotless short. And here is what that stuff consists of:

50 years after the inevitable nuclear Armageddon, the United States and its allies (now called the Market) and the USSR and its allies (now called the Confederation) have outlawed war. All territorial disputes are achieved in one-on-one battle between the great hundred-foot robots that make up the entirety of the two nations' armies, with the one country basically announcing, "I want to take over [Alaska]," and the other territory sending their best robot jock to defend it. It's Risk, basically, perhaps owing to a cultural memory that lingered after all board games were destroyed in the fires of nuclear death.

The two great robot jocks of this particular future are Achilles of the Market (Gary Graham) and Alexander of the Confederation (Paul Koslo), the former of whom is just one bout away from being done with his contract with the Market government, the latter of whom is a bloodthirsty psychopath, what with being a Russian analogue in a late-'80s cheapie action film and all. They meet to contest Alaska - which would be the first loss of a central Market territory in years - and end in a draw when Alexander is able to defend Achilles's top-secret new weaponry almost like he'd been tipped off about it. The international organisation responsible for arbitrating such things declares a rematch one week in the future, with Achilles insisting that he's earned his retirement, while his strategist Tex Conway (Michael Alldredge) and weapons designer Matsumoto (Danny Kamekona) hunt for the spy. When a genetically engineered soldier named Athena (Anne-Marie Johnson) is tapped to fight Alexander - the first woman and the first "tubie", as the new generation of lab-created humans are derisively called, to fight in robot combat - Achilles prepares to fight the battle he'd so assiduously dodged out of; for by this point, he has fallen in love with Athena, she being the sole named female in the film and all.

Given its genealogy in the hands of Charles Band and his father, producer Albert Band, Robot Jox looks unbelievably posh (that is to say: it merely looks like a very low-budget indie, not a dysfunctionally low-budget indie), and the central concept is sound enough. But it is, despite its accrual of an appreciative cult in later years, pretty fucking awful, and the reason couldn't be more obvious, since the filmmakers have owned up to it: writer Joe Haldeman wanted to make a geopolitically serious consideration of how wars by proxy might look in the future, and director/scenarist Stuart Gordon wanted to make a junky action film for kids. This tension never resolves itself; never even comes close to it. The Top Gun-esque romance between Achilles and Athena takes central stage for much too long to justify the silly tone Gordon brings to every other moment of the whole picture, and the remnants of the harder-tinged sci-fi that the director wanted to avoid making cling to the project, sad and forlorn and conspicuous in their lack of follow-through.

Of course, the single dumbest element of the film can't be blamed on anything but bad luck: Robot Jox was started in 1987, with delays in post-production owing largely to the fact that the production company had ceased to exist. An eventual 1989 release date flew by (though it did have its premiere in that year) without the film seeing actual release, as did an April, 1990 date, and eventually the film bowed in November, 1990, by which point the Soviet Union had disintegrated, leaving the film's loud and proud Cold War scenario looking a bit ridiculous, even with the fig leaf of "the Confederation" hiding things.

But just because we can forgive the film that one unusually large gaffe, that doesn't mean there's not plenty else to pick on, with the biggest problem coming in the form of its characters and the actors playing them: caught between Gordon's desire to make a kiddie matinee and the script's attempt to do something more adult, Graham and Johnson - neither of them meaningfully great actors to begin with - ended up completely lost, giving the most feeble and thinly-inhabited performances imaginable, and leaving the figures of Achilles and Athena totally uninteresting and unlikable, with their plot-driving romance thoroughly uncompelling. Koslo acquits himself better; he had a one-note villain to play and his atrocious cartoon Russkie (with an accent that sounds far more like Count Dracula; his delivery of the word "blood" in one scene seals the deal) at least feels like it has committed to a tone of relentlessly B-movie cheese. We can argue about whether or not this is an appealing tone - myself, I find it rather enervating after just a little bit - but at least it feels part of the movie around it.

The whole thing is really very daft: giant robots as war proxies is already a bit of a goofy concept that needs to be treated with a certain lightness, but Robot Jox errs on the side of being inept and inane, which I take to be a function of Gordon, whose best work (like the terrific Re-Animator) thrives on playfully excessive violence, and whose strengths are in no way suited to making something family-friendly without it feeling forced and insincere. It comes alive only during the fight scenes, which are unmistakably cheap and look 15 years out of date for a 1989 film, but have a DIY charm about them, and the robot design is stellar, whatever else is the case. The final scene is pretty great, anyway, though it comes at the end of a long slog of imbalanced melodrama and political thriller mechanics that nothing in the film is prepared to grapple with.

All in all, a piece of shit, pretty much: but it's such fun to watch! I was lucky enough to first see the movie at the 24-hour bad movie marathon B-Fest, certainly the best place in the world to watch such a movie, where its manifold failures of art and storytelling could be appreciated for their gung-ho hokiness rather than dismissed outright. That experience might still influence my viewing of the movie; I can't really say. But it seems to me that even on its own merits, Robot Jox is lovably dopey and its flippant, cartoon tone is an asset in terms of enjoying it, even as it's probably the biggest reason that the film bombs so hard at creating a legitimate reality. It's quintessentially So Bad It's Good, with just enough conviction that it's really easy to like, even while there's absolutely no chance in hell that you could ever respect it.