Villain and supervillain

In reviewing the first film in Louis Feuillade's five-part Fantômas series of 1913 and 1914, Fantômas - In the Shadow of the Guillotine, I rather snottily compared to Iron Man 3 as being "a critic-proof, and essentially quality-proof opportunity for filmgoers to spend time with a character they already knew they loved". And of course that comparison was appealing chiefly because Iron Man 3 happened to have come out so very close the the exact 100-year anniversary of the debut of the Fantômas serials, because there's actually a much better point of comparison among modern gigantic popcorn blockbusters: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone and its seven sequels. Namely, we have here an adaptation of an indescribably popular piece of genre fiction that trades on the love the audience already has for the characters and stories so fully that the movie version is able to cheat a little bit and leave at least some of the plot offscreen, trusting the viewer to already know what's going on. That's obviously a little bit awkward a century after the book's popularity has run its course.

I bring this up now, in the context of the second film in the series, Juve vs. Fantômas, because it ends up being, in perfect honesty, a bit of a shambles, plot-wise. Not that In the Shadow of the Guillotine was free of weird plot holes, it's just that they announce themselves a bit more pridefully in the sequel, which starts out already behind, as it were, and is immediately forced to play catch-up a bit (I should admit, I haven't read a single one of the novels, and I have no reason to believe that the missing plot in the films actually exists on the page). The first film had ended with Fantômas (René Navarre) and his mistress, Lady Beltham (Renée Carl) having successfully staged a prison break that nearly ended with the death of an innocent man; the second film opens with Lady Beltham having been crushed to death, though the intrepid police inspector Juve (Edmond Bréon) rather doubts this. And of course she hasn't been killed at all, though why exactly her death was faked (presumably by Fantômas himself), and at which point the two of them split up (as revealed in the third of the feature's four chapters), are details that Feuillade doesn't consider interesting enough to grace with even the vague implication of an answer.

Really, Juve vs. Fantômas feels much looser and disconnected than its forebear, at times adopting little other than the merest suggestion of an overall plot in among its anecdotal subplots, and that does make it even a bit more alienating than its archaic style. But even so, dear reader, I confess myself smitten with Juve vs. Fantômas, and not even because I successfully donned my "pretend it's 1913" cap, or had to think about doing so. If the chief appeal of In the Shadow of the Guillotine is its creation of a certain air of the inexplicable, the unpredictable, and the borderline-surreal - though surrealism, as such, hadn't been invented yet - the chief appeal of Juve vs. Fantômas is that it picks up all that strangeness and runs with it, fast as can be, with an impressive evolution in technique in the mere four months separating the films. Where the first movie was largely confined to sets, Juve vs. Fantômas spends a great deal of time, particularly in its first chapter, outside on location, and the open, bright frames that Feuillade thus creates are terrifically kinetic and physical. I admire and enjoy the cavalcade of absurdities that creep into the series with this film throughout, but the first part, "The Simplon Express Disaster" is genuinely exciting to me, ancient & unsophisticated filmmaking techniques or no. It's easy to see how the character of Fantômas made such a splash with 1910s audiences; he was their version of Heath Ledger's Joker from The Dark Knight, a figure of aimless but deadly antisocial chaos, stripped of personalising details, and safely contained within the limits of genre fiction so that he could be dealt with at no risk of actual emotional danger.

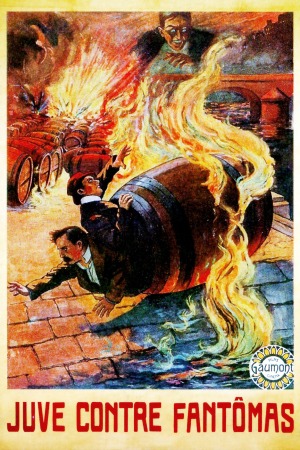

"The Simplon Express Disaster" does not contain my absolute favorite bits of Juve vs. Fantômas, though overall it's easily my favorite sequence as a whole. It opens with a bit of detectiving, as Juve and his journalist buddy Fandor (Georges Melchior) pursue the archcriminal in his disguise as gang leader Loupart, which leads them to a shady prostitute, Joséphine (Yvette Andréyor), and thence to a robbery that the Loupart gang plans to stage on a moving train. And it's here that the movie gets cooking: the train robbery is unbelievable for 1913, filmed in an actual moving train and culminating in a terrific bit of cinematic trickery as the train explodes. Fantômas ends up being denied his prize, but he's able to stage revenge on Juve and Fandor, luring them to a wine warehouse where he plans to set the barrels of alcohol on fire and kill them both. The two heroes escape by hiding in a barrel and rolling it down the dock into water, a tremendous bit of what-the-fuckery that adds a great measure of warped comedy to the whole affair.

The warped comedy, that's what does it for me. All the best parts of Juve vs. Fantômas involve criminal plots so outré that delighted disbelief is the only sane response: disbelief at the their implausibility, at the fact they were staged, at the way that we still totally buy it in the moment, thanks to Feuillade's stately presentation, which is so dignified even as the movie is at its silliest that it lends a measure of gravity and sincerity to the goings-on, whether they involve a pair of breakaway robot arms, an assassin throwing a boa constrictor at a sleeping victim wearing spikes around his midsection (modern viewer beware: the ultimate fate of that snake is damnably upsetting, a queasy reminder that animals weren't accorded anything resembling the same humane treatment four and five generations ago that they are now), or Fantômas's trick of hiding in a cistern using a wine bottle as a breathing tube, while dressed in full-on supervillain regalia, skin-tight black with a menacing hood.

As before, the contrast within the film gives it a huge amount of personality that all the decades haven't erased: the spare, authentic style and the flagrantly weird content jar against each other in a way that's really fun, though the perverse anti-cohesion of Juve vs. Fantômas makes it an awfully hard sell for a modern viewer who's not already fairly well-acquainted with the cinema of the 1900s and 1910s. On the other hand, it has something that In the Shadow of the Guillotine lacks: a real, proper hero, in the figure of Juve, who becomes a much bigger, more interesting figure here (though he's not much good at his job), big enough that not only does he get titular billing over the main character, but Bréon is even introduced, like Navarre, in a series of non-diegetic close-ups that dissolve into each other, revealing the various disguises he'll wear over the next hour. It's a quick way of establishing a character bold enough to stand against the over-the-top wicked Fantômas, and the presence of two simplistic but instantly-recognisable figures, hero and anti-hero, make what little rudiments of plot the film boasts click in a pleasingly archetypal way.

Louis Feuillade's Fantômas

Fantômas - In the Shadow of the Guillotine

Juve vs. Fantômas

The Murderous Corpse

Fantômas vs. Fantômas

The False Magistrate

I bring this up now, in the context of the second film in the series, Juve vs. Fantômas, because it ends up being, in perfect honesty, a bit of a shambles, plot-wise. Not that In the Shadow of the Guillotine was free of weird plot holes, it's just that they announce themselves a bit more pridefully in the sequel, which starts out already behind, as it were, and is immediately forced to play catch-up a bit (I should admit, I haven't read a single one of the novels, and I have no reason to believe that the missing plot in the films actually exists on the page). The first film had ended with Fantômas (René Navarre) and his mistress, Lady Beltham (Renée Carl) having successfully staged a prison break that nearly ended with the death of an innocent man; the second film opens with Lady Beltham having been crushed to death, though the intrepid police inspector Juve (Edmond Bréon) rather doubts this. And of course she hasn't been killed at all, though why exactly her death was faked (presumably by Fantômas himself), and at which point the two of them split up (as revealed in the third of the feature's four chapters), are details that Feuillade doesn't consider interesting enough to grace with even the vague implication of an answer.

Really, Juve vs. Fantômas feels much looser and disconnected than its forebear, at times adopting little other than the merest suggestion of an overall plot in among its anecdotal subplots, and that does make it even a bit more alienating than its archaic style. But even so, dear reader, I confess myself smitten with Juve vs. Fantômas, and not even because I successfully donned my "pretend it's 1913" cap, or had to think about doing so. If the chief appeal of In the Shadow of the Guillotine is its creation of a certain air of the inexplicable, the unpredictable, and the borderline-surreal - though surrealism, as such, hadn't been invented yet - the chief appeal of Juve vs. Fantômas is that it picks up all that strangeness and runs with it, fast as can be, with an impressive evolution in technique in the mere four months separating the films. Where the first movie was largely confined to sets, Juve vs. Fantômas spends a great deal of time, particularly in its first chapter, outside on location, and the open, bright frames that Feuillade thus creates are terrifically kinetic and physical. I admire and enjoy the cavalcade of absurdities that creep into the series with this film throughout, but the first part, "The Simplon Express Disaster" is genuinely exciting to me, ancient & unsophisticated filmmaking techniques or no. It's easy to see how the character of Fantômas made such a splash with 1910s audiences; he was their version of Heath Ledger's Joker from The Dark Knight, a figure of aimless but deadly antisocial chaos, stripped of personalising details, and safely contained within the limits of genre fiction so that he could be dealt with at no risk of actual emotional danger.

"The Simplon Express Disaster" does not contain my absolute favorite bits of Juve vs. Fantômas, though overall it's easily my favorite sequence as a whole. It opens with a bit of detectiving, as Juve and his journalist buddy Fandor (Georges Melchior) pursue the archcriminal in his disguise as gang leader Loupart, which leads them to a shady prostitute, Joséphine (Yvette Andréyor), and thence to a robbery that the Loupart gang plans to stage on a moving train. And it's here that the movie gets cooking: the train robbery is unbelievable for 1913, filmed in an actual moving train and culminating in a terrific bit of cinematic trickery as the train explodes. Fantômas ends up being denied his prize, but he's able to stage revenge on Juve and Fandor, luring them to a wine warehouse where he plans to set the barrels of alcohol on fire and kill them both. The two heroes escape by hiding in a barrel and rolling it down the dock into water, a tremendous bit of what-the-fuckery that adds a great measure of warped comedy to the whole affair.

The warped comedy, that's what does it for me. All the best parts of Juve vs. Fantômas involve criminal plots so outré that delighted disbelief is the only sane response: disbelief at the their implausibility, at the fact they were staged, at the way that we still totally buy it in the moment, thanks to Feuillade's stately presentation, which is so dignified even as the movie is at its silliest that it lends a measure of gravity and sincerity to the goings-on, whether they involve a pair of breakaway robot arms, an assassin throwing a boa constrictor at a sleeping victim wearing spikes around his midsection (modern viewer beware: the ultimate fate of that snake is damnably upsetting, a queasy reminder that animals weren't accorded anything resembling the same humane treatment four and five generations ago that they are now), or Fantômas's trick of hiding in a cistern using a wine bottle as a breathing tube, while dressed in full-on supervillain regalia, skin-tight black with a menacing hood.

As before, the contrast within the film gives it a huge amount of personality that all the decades haven't erased: the spare, authentic style and the flagrantly weird content jar against each other in a way that's really fun, though the perverse anti-cohesion of Juve vs. Fantômas makes it an awfully hard sell for a modern viewer who's not already fairly well-acquainted with the cinema of the 1900s and 1910s. On the other hand, it has something that In the Shadow of the Guillotine lacks: a real, proper hero, in the figure of Juve, who becomes a much bigger, more interesting figure here (though he's not much good at his job), big enough that not only does he get titular billing over the main character, but Bréon is even introduced, like Navarre, in a series of non-diegetic close-ups that dissolve into each other, revealing the various disguises he'll wear over the next hour. It's a quick way of establishing a character bold enough to stand against the over-the-top wicked Fantômas, and the presence of two simplistic but instantly-recognisable figures, hero and anti-hero, make what little rudiments of plot the film boasts click in a pleasingly archetypal way.

Louis Feuillade's Fantômas

Fantômas - In the Shadow of the Guillotine

Juve vs. Fantômas

The Murderous Corpse

Fantômas vs. Fantômas

The False Magistrate