The misery of 1952

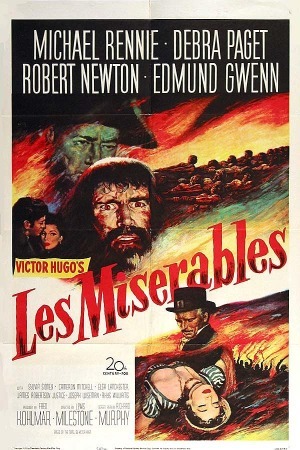

Inasmuch as it's ever the "wrong" time to adapt a movie from one of the foundational texts of contemporary Western literature, 1952 was an odd year for 20th Century Fox to mount a new American Les Misérables. The 1930s' great spate of prestige pictures based on classic 19th Century novels that had birthed the studio's first version of Victor Hugo's 1862 masterpiece, alongside everything from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to Becky Sharp to, in a slantwise way, The Life of Emile Zzzzzola had largely dried up in the post-war era, and the '50s own special iteration of the tony literary-style Serious Film for Serious People was already shaping up to be bloated historical epics set, as much as possible, in Imperial Rome or the Biblical Middle East. One can easily imagine a star-studded big-budget three-hour Les Misérables in the '60s, Hollywood's greatest decade for gargantuan, fussy European costume dramas, but nothing about the early '50s stands out as the ideal moment for such a venture.

That, maybe, is why the '52 Les Misérables (whose title, formally speaking, lacks the accent over the "é", but let's not be prigs about it) feels like such a half-formed oddity, not entirely sure of its own identity or plot, looking a bit ratty in a way that the '35 film absolutely, unequivocally does not. Perhaps it's simply a matter of the skill to zestfully film a big backlot set to look deep and alive had degraded somewhere along the way, in the era where location photography started to really come into its own; at least, the absence of a Gregg Toland behind the camera is keenly felt (the '52 movie was shot by Joseph LaShelle), and the general feeling that the movie has been slightly over-lit makes the sets look particularly set-like. Not that a '30s costume drama oozes realism and veracity, but the staginess there is typically swept up into the movie and used to the story's advantage, lending an air of pageantry. Whatever merits the '52 Les Misérables has, and they do exist in a muted way, a sense of pageantry is nowhere to be seen.

Written by Richard Murphy, the film is as much a remake of the '35 film as it is a new adaptation of the book: they are structurally identical in the first quarter, and equally dissimilar from the novel, to an extent that is impossible to credit as a coincidence. Once again, the film opens with Jean Valjean (Michael Rennie) being sentenced to prison for stealing a loaf of bread to feed a starving child (peculiarly, in this iteration it's his friend's wife and children, not his own sister, whose suffering drives him to crime, unless I misunderstood something) and sentenced to be a literal galley slave on literal, anachronistic boats. Heck, director Lewis Milestone even copies Richard Boleslawski's flourish of panning down to the forlorn loaf of bread with a knife sticking out of it, as an "aha! can you believe the maddening imbalance of this justice system?" gesture. In prison, For the next little while, the films proceed in close company, though there are subtleties and a couple variations in Valjean's galley experience. Again, he crosses paths with dogged policeman Javert (Robert Newton), here given the first name Etienne; again, he suffers the slings and arrows of a cruel French citizenry that cares not a whit for the humanity of paroled convicts, until he encounters the kindly Bishop Courbet (Edmund Gwenn), who teaches him about mercy and justice.

All of this proceeds a bit faster than the earlier movie, as it must: this Les Misérables races by at just 105 minutes, and it needs to take its time getting places. Or so you'd think. In fact, after Valjean leaves the bishop, the '52 film starts to break away completely from Victor Hugo and any other adaptation of which I am aware, before or since, eventually turning into something that we can call Les Misérables more because of the character names and the broad shape of events are the same. The emphasis on events is completely different: now, for example, we see in some exacting detail how Valjean rise to prominence in provincial France and became the mayor of a small town, and how he brought along craftsman Robert (James Robertson Justice) to be his confidant and right-hand man, deeply useful information in a film as strapped for time as any feature-length adaptation of Les Misérables must by necessity be. It's for reasons like this that the entirety of the sequences set in Paris and involving the barricades - three-fifths of the massive book - are dealt with in something close to 30 minutes.

In brief, it's the least-faithful adaptation of the book that I have ever seen, playing more like a fantasia on the themes of Les Misérables than as Les Misérables itself. Desperate prostitute Fantine (Sylvia Sidney) is, in grand '50s tradition, stripped of her profession, even in the most coded, implied terms, and thus turned into a rather peculiar mess of a character as a result: why she'd excite Javert's antipathy so much is a question that even the characters in the movie don't seem to understand exactly, and since we don't have any real idea of the depths to which she's sunk (knowing only that she's been fired from Valjean's factory), it's awfully hard to care very much about her fate. Making things even weirder, Murphy inserts a brand new scene in which Valjean brings Fantine's young daughter Cosette (Patsy Weil) to see her, some decent while before she dies, thereby taking away any sense we have of Fantine as a tragic figure and making Valjean's morally righteous decision to raise Cosette as best he can significantly less lofty and cosmic in its scope.

Eventually, after far too long, we arrive in Paris, with a grown-up Cosette (Debra Paget) flirting with student revolutionary Marius (Cameron Mitchell), hypercorrecting the pronunciation of his last name so that the "u" sounds like the vowel sound in "boot" - and what, exactly, student revolutionary Marius is revolting against is something that we never, ever find out, for besides little child revolutionary Gavroche (Robert Hyatt) popping up a couple of times and using the honorific "Citizen", we don't see much of the revolution, or have a concept of its aims, other than a quick mention that he's a Bonapartist, not a Republican (and for this I am happy: it's an important detail in the book that doesn't crop up in most English-language movies, owing to it requiring more knowledge of 19th French politics than the target audience can be trusted to possess), all in keeping with the political sensitivity of the 1950s, when even the hint of an approving depiction of aggressively leftist ideals would nave been simply impossible. The supremely unpleasant possibility is raised that Valjean is in love with his ward, and for very little obvious reason, he makes a quick trip to the barricades to save Marius's life, before Javert tracks him down one last time. As in the '35 film, the movie ends immediately upon the conclusion of the Valjean/Javert plot, ignoring the significant thematic depths yet to play out in the book.

Setting aside its wildly unsatisfying nature as a film derived, oh so loosely, from Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, the film's narrative is still awfully damn messy, rotating characters in and out arbitrarily - Fantine never seems fully integrated into the drama, even on her deathbed - and turning the last 20 minutes into such a confusing hash of disconnected plot points that even with the book strong in my mind, I couldn't figure out what was going on and why. It's rushed and draggy in exactly the wrong places, spending lots of times on things that don't matter (the entire existence of new character Robert, Valjean's rise to the mayoralty), and barely mentioning things that do (the revolution, which is presented so vaguely that it's hard to say for certain whether it's the 1823 June Rebellion or not, and was one of the thematic cornerstones of the book).

Not that any feature-length Les Misérables has exactly been a model of pacing, mind you; many of the film's worst problems are nothing but exaggerations of things already present in the '35 movie, and that was a genuinely successful, enjoyable piece of filmmaking. The difference being that the '35 film had Toland's wonderful cinematography to make up for Boleslawski's general impersonality as a director, while Lewis Milestone, whose career includes genuine masterpieces (most famously All Quiet on the Western Front), had by the '50s run out of steam as a filmmaker, and treats this material without much of either inspiration or flair. It is a flat movie; a movie stuck in a studio-bound fantasyland version of France that doesn't fit the lighting or the acting. It doesn't have the tang of the real, and thus there isn't any of that misery that gives the property its title.

What it does have, at least, is the same thing the earlier film had: a strong pair of central performances. Not that Rennie and Newton are the same as Frederic March and Charles Laughton, by any yardstick; but given the later film's changed emphasis and perspective, they give absolutely the right performances for the material. Newton in particular is responsible for breathing life into a wholly transformed Javert, no longer the stony ideologue of the book, but something much closer to a Satanic figure, delighting in wickedness just because nobody prevents him from being evil. Almost the first thing that we see of him is his barely-subdued exultation at knowing that his convict father died under his supervision; as the film progresses he takes a far more actively villainous role than Hugo ever depicted, less a creature of implacable, brittle Catholic morality than a savage bandit doing ill for the sake of it. None of this, by the way, is actually to the film's shame: once you get over the fact that it's absolutely not the book, the film's idea of Javert is fun in a limited way, and Newton's devilish self-satisfaction, his way of sneaking and prowling as he walks and looks about, is perhaps the single best thing about the film (it's a little amazing to see that his performance, and the way the role is written, is less nuanced here than when he played a for-real pirate in Treasure Island two years prior.

Rennie's Valjean is good, though not nearly that good; he's a fine enough actor but there's too much of the '50s Noble Block of Wood style of characterisation about him, and his expressive, declamatory performance - the kind of acting that '50s prestige pictures of the less realist school tended to encourage - isn't a terrifically good fit for the melodramatic scenario. Still, he captures the dignity and intelligence of Valjean awfully well, even as the script gives him increasingly little to do with it.

As in the '35 film, the great performances mostly stop after that: Sidney is miscast, a bit too matronly and put-together, and that's the worst you can say about her; that's enough to put put her above Paget, bringing a jarring, anachronistic modernism to her fresh-faced adolescent Cosette (the bobby-soxer ponytail doesn't help matters at all, but that's probably not her fault), and the less said about Mitchells' foggy Marius, the better.

No, it is not much of a good movie: clumsy story structure, passionless visuals, a clobbering, anonymous score that sounds like it was taken from a B-list WWII movie. What strength it has comes largely from the strength inherent to the material: Les Misérables inherently works, no matter what limitations you put on it, and not matter how much the film seeks to sand off it's grandiose emotional sprawl, some of that peeks through. Though not nearly as much peeks through in other versions, and while the film has its charm, it does everything the 1935 film does wrong and more, while not doing the good things that film does nearly as well. But Rennie and Newton carry it through, anyway, and it's hardly a waste of 105 minutes, even though I cannot imagine ever telling somebody that it was a genuinely worthy use of that same time.

That, maybe, is why the '52 Les Misérables (whose title, formally speaking, lacks the accent over the "é", but let's not be prigs about it) feels like such a half-formed oddity, not entirely sure of its own identity or plot, looking a bit ratty in a way that the '35 film absolutely, unequivocally does not. Perhaps it's simply a matter of the skill to zestfully film a big backlot set to look deep and alive had degraded somewhere along the way, in the era where location photography started to really come into its own; at least, the absence of a Gregg Toland behind the camera is keenly felt (the '52 movie was shot by Joseph LaShelle), and the general feeling that the movie has been slightly over-lit makes the sets look particularly set-like. Not that a '30s costume drama oozes realism and veracity, but the staginess there is typically swept up into the movie and used to the story's advantage, lending an air of pageantry. Whatever merits the '52 Les Misérables has, and they do exist in a muted way, a sense of pageantry is nowhere to be seen.

Written by Richard Murphy, the film is as much a remake of the '35 film as it is a new adaptation of the book: they are structurally identical in the first quarter, and equally dissimilar from the novel, to an extent that is impossible to credit as a coincidence. Once again, the film opens with Jean Valjean (Michael Rennie) being sentenced to prison for stealing a loaf of bread to feed a starving child (peculiarly, in this iteration it's his friend's wife and children, not his own sister, whose suffering drives him to crime, unless I misunderstood something) and sentenced to be a literal galley slave on literal, anachronistic boats. Heck, director Lewis Milestone even copies Richard Boleslawski's flourish of panning down to the forlorn loaf of bread with a knife sticking out of it, as an "aha! can you believe the maddening imbalance of this justice system?" gesture. In prison, For the next little while, the films proceed in close company, though there are subtleties and a couple variations in Valjean's galley experience. Again, he crosses paths with dogged policeman Javert (Robert Newton), here given the first name Etienne; again, he suffers the slings and arrows of a cruel French citizenry that cares not a whit for the humanity of paroled convicts, until he encounters the kindly Bishop Courbet (Edmund Gwenn), who teaches him about mercy and justice.

All of this proceeds a bit faster than the earlier movie, as it must: this Les Misérables races by at just 105 minutes, and it needs to take its time getting places. Or so you'd think. In fact, after Valjean leaves the bishop, the '52 film starts to break away completely from Victor Hugo and any other adaptation of which I am aware, before or since, eventually turning into something that we can call Les Misérables more because of the character names and the broad shape of events are the same. The emphasis on events is completely different: now, for example, we see in some exacting detail how Valjean rise to prominence in provincial France and became the mayor of a small town, and how he brought along craftsman Robert (James Robertson Justice) to be his confidant and right-hand man, deeply useful information in a film as strapped for time as any feature-length adaptation of Les Misérables must by necessity be. It's for reasons like this that the entirety of the sequences set in Paris and involving the barricades - three-fifths of the massive book - are dealt with in something close to 30 minutes.

In brief, it's the least-faithful adaptation of the book that I have ever seen, playing more like a fantasia on the themes of Les Misérables than as Les Misérables itself. Desperate prostitute Fantine (Sylvia Sidney) is, in grand '50s tradition, stripped of her profession, even in the most coded, implied terms, and thus turned into a rather peculiar mess of a character as a result: why she'd excite Javert's antipathy so much is a question that even the characters in the movie don't seem to understand exactly, and since we don't have any real idea of the depths to which she's sunk (knowing only that she's been fired from Valjean's factory), it's awfully hard to care very much about her fate. Making things even weirder, Murphy inserts a brand new scene in which Valjean brings Fantine's young daughter Cosette (Patsy Weil) to see her, some decent while before she dies, thereby taking away any sense we have of Fantine as a tragic figure and making Valjean's morally righteous decision to raise Cosette as best he can significantly less lofty and cosmic in its scope.

Eventually, after far too long, we arrive in Paris, with a grown-up Cosette (Debra Paget) flirting with student revolutionary Marius (Cameron Mitchell), hypercorrecting the pronunciation of his last name so that the "u" sounds like the vowel sound in "boot" - and what, exactly, student revolutionary Marius is revolting against is something that we never, ever find out, for besides little child revolutionary Gavroche (Robert Hyatt) popping up a couple of times and using the honorific "Citizen", we don't see much of the revolution, or have a concept of its aims, other than a quick mention that he's a Bonapartist, not a Republican (and for this I am happy: it's an important detail in the book that doesn't crop up in most English-language movies, owing to it requiring more knowledge of 19th French politics than the target audience can be trusted to possess), all in keeping with the political sensitivity of the 1950s, when even the hint of an approving depiction of aggressively leftist ideals would nave been simply impossible. The supremely unpleasant possibility is raised that Valjean is in love with his ward, and for very little obvious reason, he makes a quick trip to the barricades to save Marius's life, before Javert tracks him down one last time. As in the '35 film, the movie ends immediately upon the conclusion of the Valjean/Javert plot, ignoring the significant thematic depths yet to play out in the book.

Setting aside its wildly unsatisfying nature as a film derived, oh so loosely, from Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, the film's narrative is still awfully damn messy, rotating characters in and out arbitrarily - Fantine never seems fully integrated into the drama, even on her deathbed - and turning the last 20 minutes into such a confusing hash of disconnected plot points that even with the book strong in my mind, I couldn't figure out what was going on and why. It's rushed and draggy in exactly the wrong places, spending lots of times on things that don't matter (the entire existence of new character Robert, Valjean's rise to the mayoralty), and barely mentioning things that do (the revolution, which is presented so vaguely that it's hard to say for certain whether it's the 1823 June Rebellion or not, and was one of the thematic cornerstones of the book).

Not that any feature-length Les Misérables has exactly been a model of pacing, mind you; many of the film's worst problems are nothing but exaggerations of things already present in the '35 movie, and that was a genuinely successful, enjoyable piece of filmmaking. The difference being that the '35 film had Toland's wonderful cinematography to make up for Boleslawski's general impersonality as a director, while Lewis Milestone, whose career includes genuine masterpieces (most famously All Quiet on the Western Front), had by the '50s run out of steam as a filmmaker, and treats this material without much of either inspiration or flair. It is a flat movie; a movie stuck in a studio-bound fantasyland version of France that doesn't fit the lighting or the acting. It doesn't have the tang of the real, and thus there isn't any of that misery that gives the property its title.

What it does have, at least, is the same thing the earlier film had: a strong pair of central performances. Not that Rennie and Newton are the same as Frederic March and Charles Laughton, by any yardstick; but given the later film's changed emphasis and perspective, they give absolutely the right performances for the material. Newton in particular is responsible for breathing life into a wholly transformed Javert, no longer the stony ideologue of the book, but something much closer to a Satanic figure, delighting in wickedness just because nobody prevents him from being evil. Almost the first thing that we see of him is his barely-subdued exultation at knowing that his convict father died under his supervision; as the film progresses he takes a far more actively villainous role than Hugo ever depicted, less a creature of implacable, brittle Catholic morality than a savage bandit doing ill for the sake of it. None of this, by the way, is actually to the film's shame: once you get over the fact that it's absolutely not the book, the film's idea of Javert is fun in a limited way, and Newton's devilish self-satisfaction, his way of sneaking and prowling as he walks and looks about, is perhaps the single best thing about the film (it's a little amazing to see that his performance, and the way the role is written, is less nuanced here than when he played a for-real pirate in Treasure Island two years prior.

Rennie's Valjean is good, though not nearly that good; he's a fine enough actor but there's too much of the '50s Noble Block of Wood style of characterisation about him, and his expressive, declamatory performance - the kind of acting that '50s prestige pictures of the less realist school tended to encourage - isn't a terrifically good fit for the melodramatic scenario. Still, he captures the dignity and intelligence of Valjean awfully well, even as the script gives him increasingly little to do with it.

As in the '35 film, the great performances mostly stop after that: Sidney is miscast, a bit too matronly and put-together, and that's the worst you can say about her; that's enough to put put her above Paget, bringing a jarring, anachronistic modernism to her fresh-faced adolescent Cosette (the bobby-soxer ponytail doesn't help matters at all, but that's probably not her fault), and the less said about Mitchells' foggy Marius, the better.

No, it is not much of a good movie: clumsy story structure, passionless visuals, a clobbering, anonymous score that sounds like it was taken from a B-list WWII movie. What strength it has comes largely from the strength inherent to the material: Les Misérables inherently works, no matter what limitations you put on it, and not matter how much the film seeks to sand off it's grandiose emotional sprawl, some of that peeks through. Though not nearly as much peeks through in other versions, and while the film has its charm, it does everything the 1935 film does wrong and more, while not doing the good things that film does nearly as well. But Rennie and Newton carry it through, anyway, and it's hardly a waste of 105 minutes, even though I cannot imagine ever telling somebody that it was a genuinely worthy use of that same time.