Hail to the chef

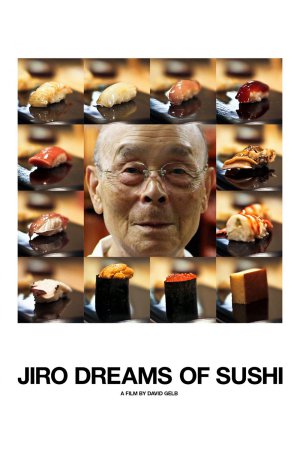

In Tokyo, there is found one of the most highly-regarded restaurants in the world, Sukiyabashi Jiro. It is a 10-seat sushi bar that is the smallest establishment awarded a perfect three-star rating from the prestigious Michelin Guide, and the first sushi restaurant to win that honor; its proprietor, Ono Jiro, has dedicated an entire lifetime to his craft, knowing and caring about nothing else besides becoming the finest sushi chef that he's able to be.

The man and the restaurant are the subject of David Gelb's intensely focused documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, filmed when Ono was 85 years old, and no closer to thinking about retiring than when he started, so many decades ago. At only 82 minutes long, the film lacks any excess of philosophy or context: it was the end result of Gelb's intention to make a much broader documentary about sushi culture generally, turned into the study of a single restaurant only when it became clear that Ono would be all the subject needed to make a fascinating feature-length project; and lo and behold, that has turned out to be exactly the case. For Ono is a fascinating figure, a master artist in his own right and a great leader of men (one of the points built up slowly throughout the movie and clarified in a late scene is that it's the work done by the entire staff of Sukiyabashi Jiro, and not simply Ono himself, that makes the food so sublime), and a craftsman whose single-minded focus on perfecting himself in one single aspect of life has turned him into something at once more and less than other humans.

Put another way: Jiro Dreams of Sushi is, at heart, not about the making of sushi - though it's enough about that, and the sushi in question is breathtakingly beautiful enough, that I left the movie more anxious to go and eat a costly meal than at any point since Ratatouille - but about obsession and perfectionism, divorced from any moral judgments in either direction. One of the things we learn about Ono Jiro early on, which turns out to be a significant throughline as the movie progresses is that he has two sons: the elder, Yoshikazu, is currently serving as apprentice and second-in-command to his father, and will take over the operation of the restaurant in full whenever death or age force Jiro out; the young, Takashi, currently runs a restaurant of his own. It's obvious that, whatever fondness the elder Ono has to his offspring, he's not a warm or demonstrative father, nor an especially forgiving one. It is revealed, briefly and casually, that Yoshikazu hated the sushi restaurant when he first started working there, and we can assume only the inflexible expectations of Jiro - for if there's one word to define the man that we see throughout the movie, it's "inflexible" - held him in place long enough to come to respect the artistry and desire to create a singular, perfect experience that has over the years left the restaurant with its world-class reputation.

For that, too, is what comes up through Jiro Dreams of Sushi: it is not a story about an Ahab-like tyrant, ruthlessly pursuing flawless work from all of his staff (happily admitting that he demands even more of Yoshikazu than anyone else) and openly caring more about his precious sushi than his sons, though he does demand such work, and he does so care. But it is not in some monstrous way that comes from a mean desire for power, but out of a love for the thing he does, and an absolute refusal to permit anyone else to dilute that love by not committing to it. Certainly, by the end of the movie, and long before, we get a very clear idea of just how much Ono puts of himself in to the restaurant bearing his name, and how anxious to make sure that every single person who eats there has a completely perfect experience: little notes about the way that he will adjust the way he serves the food based on how he observes the diners' movements and positions, for example, or the passage in the film discussing how much thought and effort went into creating the restaurant's standardised menu.

The film might be about an unforgiving, severe artist, then, but it is clear that there is nobody to whom Ono is more severe than himself. And his reward for it is a legacy that few chefs in the modern world could claim for their own: to be widely regarded as the best in his field (a reputation that holds more in the Michelin-besotted West than in Tokyo itself, I have read; "best chef ever" competitions not being held in very much value by the Japanese), and to have a legion of fans who regard their every interaction with him as a priceless moment of food consumption. If Ono is a perfectionist, the film argues that this means that what he produces is thus, by definition, perfection, and what emerges is not a condemnation of his work ethic, but a celebration of the wonderful things thereby created, with just enough awareness that he's a prickly and in some ways disagreeable old man to avoid seeming like an exercise in hero worship.

Instead, the film is simply about the life and mind and discipline of an artist: it does not try to make any broad claims about him beyond simply observing, this is what he does, this is why it matters, and this is his legacy. Certainly, everyone around him, even those ruefully recalling the impatience and abuse that has come their way, have an undisguised admiration and love for Ono, and for the great things they have achieved under his tutelage. It is not a great, universal film, nor a perfectly made one (in particular, the use of pre-existing music is frequently annoying, especially when the Philip Glass starts to pile up at the end), but it's as rich and enticing as any study of an artist's temperament in the last few years, and one of the most enjoyable documentaries of 2012.

8/10

The man and the restaurant are the subject of David Gelb's intensely focused documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, filmed when Ono was 85 years old, and no closer to thinking about retiring than when he started, so many decades ago. At only 82 minutes long, the film lacks any excess of philosophy or context: it was the end result of Gelb's intention to make a much broader documentary about sushi culture generally, turned into the study of a single restaurant only when it became clear that Ono would be all the subject needed to make a fascinating feature-length project; and lo and behold, that has turned out to be exactly the case. For Ono is a fascinating figure, a master artist in his own right and a great leader of men (one of the points built up slowly throughout the movie and clarified in a late scene is that it's the work done by the entire staff of Sukiyabashi Jiro, and not simply Ono himself, that makes the food so sublime), and a craftsman whose single-minded focus on perfecting himself in one single aspect of life has turned him into something at once more and less than other humans.

Put another way: Jiro Dreams of Sushi is, at heart, not about the making of sushi - though it's enough about that, and the sushi in question is breathtakingly beautiful enough, that I left the movie more anxious to go and eat a costly meal than at any point since Ratatouille - but about obsession and perfectionism, divorced from any moral judgments in either direction. One of the things we learn about Ono Jiro early on, which turns out to be a significant throughline as the movie progresses is that he has two sons: the elder, Yoshikazu, is currently serving as apprentice and second-in-command to his father, and will take over the operation of the restaurant in full whenever death or age force Jiro out; the young, Takashi, currently runs a restaurant of his own. It's obvious that, whatever fondness the elder Ono has to his offspring, he's not a warm or demonstrative father, nor an especially forgiving one. It is revealed, briefly and casually, that Yoshikazu hated the sushi restaurant when he first started working there, and we can assume only the inflexible expectations of Jiro - for if there's one word to define the man that we see throughout the movie, it's "inflexible" - held him in place long enough to come to respect the artistry and desire to create a singular, perfect experience that has over the years left the restaurant with its world-class reputation.

For that, too, is what comes up through Jiro Dreams of Sushi: it is not a story about an Ahab-like tyrant, ruthlessly pursuing flawless work from all of his staff (happily admitting that he demands even more of Yoshikazu than anyone else) and openly caring more about his precious sushi than his sons, though he does demand such work, and he does so care. But it is not in some monstrous way that comes from a mean desire for power, but out of a love for the thing he does, and an absolute refusal to permit anyone else to dilute that love by not committing to it. Certainly, by the end of the movie, and long before, we get a very clear idea of just how much Ono puts of himself in to the restaurant bearing his name, and how anxious to make sure that every single person who eats there has a completely perfect experience: little notes about the way that he will adjust the way he serves the food based on how he observes the diners' movements and positions, for example, or the passage in the film discussing how much thought and effort went into creating the restaurant's standardised menu.

The film might be about an unforgiving, severe artist, then, but it is clear that there is nobody to whom Ono is more severe than himself. And his reward for it is a legacy that few chefs in the modern world could claim for their own: to be widely regarded as the best in his field (a reputation that holds more in the Michelin-besotted West than in Tokyo itself, I have read; "best chef ever" competitions not being held in very much value by the Japanese), and to have a legion of fans who regard their every interaction with him as a priceless moment of food consumption. If Ono is a perfectionist, the film argues that this means that what he produces is thus, by definition, perfection, and what emerges is not a condemnation of his work ethic, but a celebration of the wonderful things thereby created, with just enough awareness that he's a prickly and in some ways disagreeable old man to avoid seeming like an exercise in hero worship.

Instead, the film is simply about the life and mind and discipline of an artist: it does not try to make any broad claims about him beyond simply observing, this is what he does, this is why it matters, and this is his legacy. Certainly, everyone around him, even those ruefully recalling the impatience and abuse that has come their way, have an undisguised admiration and love for Ono, and for the great things they have achieved under his tutelage. It is not a great, universal film, nor a perfectly made one (in particular, the use of pre-existing music is frequently annoying, especially when the Philip Glass starts to pile up at the end), but it's as rich and enticing as any study of an artist's temperament in the last few years, and one of the most enjoyable documentaries of 2012.

8/10