The 48th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/15 & 10/16 & 10/19

World premiere: 23 September, 2012, San Sebastian International Film Festival

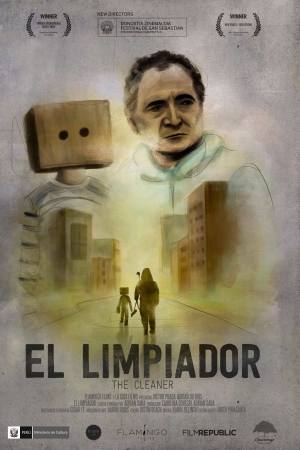

Part of me wants to eschew convention and not bother with any kind of synopsis for The Cleaner, the first feature by Peruvian writer-director Adriana Saba; and I will not indulge in this wish only because I am not clever enough to know how else to go about discussing the movie.

But I fear that if I describe the plot in even the shallowest detail, it will sound as hokey and awful to you as it sounds to me, even knowing that the film itself is neither hokey nor awful: the city of Lima is plagued with an unheard-of plague in which sufferers go from perfectly fine to drenched in sweat to so tired they can barely stand to dead on the ground in anywhere from four to twelve hours. And here there is a man, Eusebio (Victor Prada), whose job is to thoroughly scrub and sterilise the places that bodies are found; and he is a sullen, disconnected, emotionally barren sort, as you would not necessarily be shocked to learn, given the nature of his work and all. But then, one day, he finds a young boy, Joaquin (Adrian Du Bois) in an apartment with his dead mother - one of the wrinkles of this disease is that it does not seem to affect the young - and though he initially takes the boy with him solely in the hope of dumping him off at the first available welfare officer's desk, soon the old misanthrope has been given a new injection of humanity thanks to the quiet orphan.

There are so many ways that this could be too grueling for words: a world of almost universal suffering, with the affection between a lost man and a hopeful little boy, and you can almost see the Benignis dancing in your mind's eye. But there is nothing of treacle or unearned sentiment in The Cleaner; it is a hard but meaningful, and potent movie. Hells potent, as we say in the criticking business.

One basic reason for this - if "basic" is the word - is Prada, whose laconic acting admits none of the dewy-eyed Oscar clip moments one might fear. He looks, and carries himself, like an extremely worn-out man, someone who has moved beyond despair and hopelessness to a kind of deadness where even the memory of hope has been forgotten; and his reaction to the boy's presence in his life consistently lags a bit behind where the script apparently thinks it should be, giving us the impression that Eusebio actually has no idea why he's driven to be so nice to this boy, only realising after the fact that he's become a human being again.

The more over-arching reason, though, is that Saba simply isn't interested in sentiment: uplift when it feels right, yes, and there are parts of The Cleaner that are very damn uplifting, indeed. But this is a formally harsh movie about a nasty world, right from the show-off opening sequence, in which an unnamed man stands at the side of the road, watching cars go by for a good long while, and just when we're drifiting into a reverie, he runs into traffic, dying instantly. You know, that kind of movie, the kind with many long takes in which little happens; so that when things do happen, it's either shocking and alarming, or it happens so slowly that we catch ourselves by surprising in noticing it.

And if there's a certain familiarity to this approach, which has been a bit overused in the artier reaches of cinema this past decade and some - it's to the point in my festival coverage where I feel loopy enough that I'm willing to pun that Saba has gotten himself stuck in the Tarr pits - The Cleaner never comes close to feeling as derivative as it almost certainly is, given that Saba and cinematographer César Fe are honestly pretty fearless in setting up their tableaux, and many of them really are exactly as powerful as they should be to get the idea across of a world going straight to hell on the one side, and two people finding a way to carve a domestic haven out in that world on the other: e.g. a shot of Eusebio in an empty terminal, scrubbing around the vastness of that space - yes, that's another overdone trick (spaces that you never, ever expect to see vacant, and there they are, devoid of life), but it's overdone because it always works - for minutes upon minutes, until the isolation of it is about to drive you mad.

On top of all that, the film has a barbed sense of black humor (thrashing about for a bedtime story, Eusebio resorts to reading to Joaquin, in patient tones, from a television user manual) that goes along very well with its dry, reserved central performance and overall sense of deliberate pacing; the movie is slow but thoughtful, and when it cracks a rare smile, the effect is unexpected enough to give it more freshness than it might have otherwise done. And then, of course, the thing it all rests on: the relationship between the two characters really is that effective, tender, and real, developed so cautiously by the filmmaker that it never seems arbitrary, underplayed enough so that it's never cloying, and by the film's end (a bravura single-take scene lasting some six minutes or more and running through a whole avalanche of emotions), The Cleaner has actually managed to be just as sweet as it was brutal in the beginning. There are a few missteps - an airy, muzaky score; the lack of any startling originality in the filmmaking - but they're pittances next to the film's precision and emotional impact.

8/10

World premiere: 23 September, 2012, San Sebastian International Film Festival

Part of me wants to eschew convention and not bother with any kind of synopsis for The Cleaner, the first feature by Peruvian writer-director Adriana Saba; and I will not indulge in this wish only because I am not clever enough to know how else to go about discussing the movie.

But I fear that if I describe the plot in even the shallowest detail, it will sound as hokey and awful to you as it sounds to me, even knowing that the film itself is neither hokey nor awful: the city of Lima is plagued with an unheard-of plague in which sufferers go from perfectly fine to drenched in sweat to so tired they can barely stand to dead on the ground in anywhere from four to twelve hours. And here there is a man, Eusebio (Victor Prada), whose job is to thoroughly scrub and sterilise the places that bodies are found; and he is a sullen, disconnected, emotionally barren sort, as you would not necessarily be shocked to learn, given the nature of his work and all. But then, one day, he finds a young boy, Joaquin (Adrian Du Bois) in an apartment with his dead mother - one of the wrinkles of this disease is that it does not seem to affect the young - and though he initially takes the boy with him solely in the hope of dumping him off at the first available welfare officer's desk, soon the old misanthrope has been given a new injection of humanity thanks to the quiet orphan.

There are so many ways that this could be too grueling for words: a world of almost universal suffering, with the affection between a lost man and a hopeful little boy, and you can almost see the Benignis dancing in your mind's eye. But there is nothing of treacle or unearned sentiment in The Cleaner; it is a hard but meaningful, and potent movie. Hells potent, as we say in the criticking business.

One basic reason for this - if "basic" is the word - is Prada, whose laconic acting admits none of the dewy-eyed Oscar clip moments one might fear. He looks, and carries himself, like an extremely worn-out man, someone who has moved beyond despair and hopelessness to a kind of deadness where even the memory of hope has been forgotten; and his reaction to the boy's presence in his life consistently lags a bit behind where the script apparently thinks it should be, giving us the impression that Eusebio actually has no idea why he's driven to be so nice to this boy, only realising after the fact that he's become a human being again.

The more over-arching reason, though, is that Saba simply isn't interested in sentiment: uplift when it feels right, yes, and there are parts of The Cleaner that are very damn uplifting, indeed. But this is a formally harsh movie about a nasty world, right from the show-off opening sequence, in which an unnamed man stands at the side of the road, watching cars go by for a good long while, and just when we're drifiting into a reverie, he runs into traffic, dying instantly. You know, that kind of movie, the kind with many long takes in which little happens; so that when things do happen, it's either shocking and alarming, or it happens so slowly that we catch ourselves by surprising in noticing it.

And if there's a certain familiarity to this approach, which has been a bit overused in the artier reaches of cinema this past decade and some - it's to the point in my festival coverage where I feel loopy enough that I'm willing to pun that Saba has gotten himself stuck in the Tarr pits - The Cleaner never comes close to feeling as derivative as it almost certainly is, given that Saba and cinematographer César Fe are honestly pretty fearless in setting up their tableaux, and many of them really are exactly as powerful as they should be to get the idea across of a world going straight to hell on the one side, and two people finding a way to carve a domestic haven out in that world on the other: e.g. a shot of Eusebio in an empty terminal, scrubbing around the vastness of that space - yes, that's another overdone trick (spaces that you never, ever expect to see vacant, and there they are, devoid of life), but it's overdone because it always works - for minutes upon minutes, until the isolation of it is about to drive you mad.

On top of all that, the film has a barbed sense of black humor (thrashing about for a bedtime story, Eusebio resorts to reading to Joaquin, in patient tones, from a television user manual) that goes along very well with its dry, reserved central performance and overall sense of deliberate pacing; the movie is slow but thoughtful, and when it cracks a rare smile, the effect is unexpected enough to give it more freshness than it might have otherwise done. And then, of course, the thing it all rests on: the relationship between the two characters really is that effective, tender, and real, developed so cautiously by the filmmaker that it never seems arbitrary, underplayed enough so that it's never cloying, and by the film's end (a bravura single-take scene lasting some six minutes or more and running through a whole avalanche of emotions), The Cleaner has actually managed to be just as sweet as it was brutal in the beginning. There are a few missteps - an airy, muzaky score; the lack of any startling originality in the filmmaking - but they're pittances next to the film's precision and emotional impact.

8/10

Categories: ciff, peruvian cinema, post-apocalypse, south american cinema, warm fuzzies