Blockbuster History: METAL!!!!!!!!!

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the jukebox musical Rock of Ages turns the nihilism and filthiness of the '80s hair metal lifestyle into a fluffy rom-com for middle-aged ladies to titter at. Let us resist this trend by returning the an age when metal was still a living, breathing thing, to be treated with the respect - which is to say, the "respect" - it deserved.

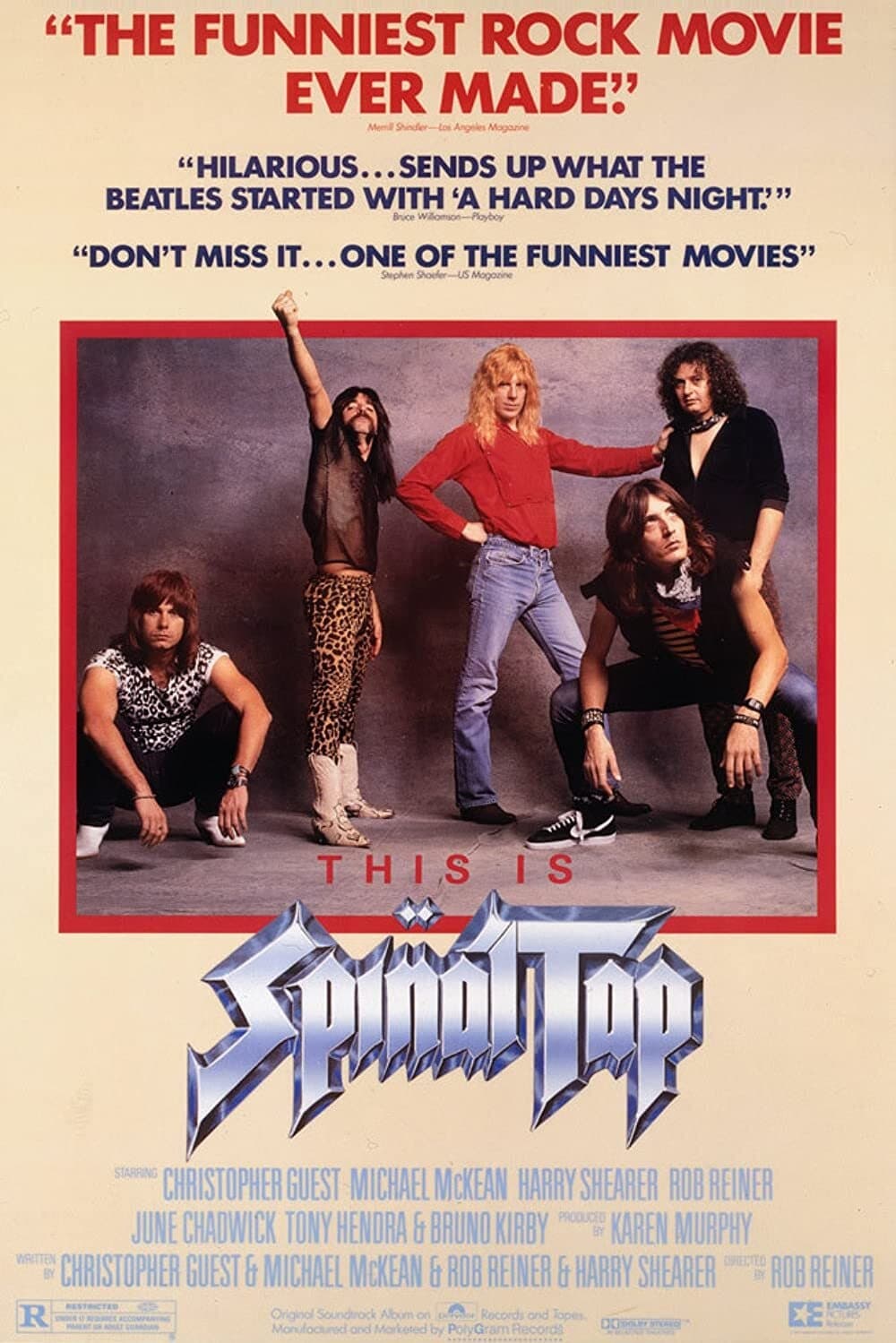

This Is Spinal Tap is ultimately a cult movie, but doesn't it feel wrong, somehow, to describe it that way? For it is one of those very special cult movies, like The Big Lebowski or The Rocky Horror Picture Show, that has also managed to colonise the mainstream without ever quite becoming a mainstream classic; it still, nearly thirty years after an initial release that found it tank at the box office, quite without special attention, feels odd and grubby and very much not like anything else that has been made in all the time since then. And this is maybe the difference between a cult classic that is fully absorbed into the wide body of pop culture versus one that remains willfully cultish: even though just about everyone probably recognises in at least a dim way the quote "these go up to eleven", as they do the idea of a rug tying the room together, or the sight of Tim Curry in fishnets and a corset, this has not been enough to domesticate the film. It is still not "normal", with its weird and experimental structure having been copied only a very few times since - the most prominent examples having been conceived and directed by one of its lead actors - and retaining a transgressive feeling of "wait, no, that's not how movies work" even after it's been long-canonised as one of the funniest American movies of the 1980s. I suppose this is a good thing: returning to Spinal Tap always brings with it a pronounced sense of discovery, a freshness that is uncommon with movies generally and unspeakably rare in a comedy, the genre most likely to wear thin after too much exposure and multiple viewings.

I could presume you know the film's hook, but at the risk of stating the obvious: Spinal Tap is presented as the work of indie documentarian Marty DiBergi (Rob Reiner, who also made his directorial debut with this feature), a huge fan of the British rock group Spinal Tap, who in 1982 were preparing their first American tour in six years. DiBergi, a fanboy if ever there was one, jumped on the chance to follow his rock gods around the country, and in doing so captured a snapshot of a rock group just about ready to collapse from exhaustion and malnutrition: singer David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean) and lead guitarist Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest) have been doing this for 17 years as the movie opens, and in that time have observed an initial burst of enthusiasm turn into almost complete obscurity, from which the group hopes to emerge by means of a particularly crude, sexually suggestive metal album titled Smell the Glove. The tour proves to be almost non-stop disasters, instigated in large part by the group's own colossal idiocy and venality, and by the time Spinal Tap reaches the west coast, St. Hubbins and Tufnel are just about ready to murder each other in frustration at the band's apparent dead-end trajectory.

Of course, what we have on our hands is the world's most prominent (though not its first) mockumentary, in which the visual language of non-fiction cinema is copied as precisely as possible in order to create the illusion that Spinal Tap, along with St. Hubbins, Tufnel, bassist Derek Smalls (Harry Shearer), and all their hangers-on actually existed. Reportedly, it even managed to trick some people way back in '84, though I cannot imagine how that is possible: it has writing and acting credits just like a normal scripted movie, though in point of fact much of the film was improvised around a narrative skeleton. And this, as Guest would prove with his own trio of improvised mockumentaries (Waiting for Guffman, 1996; Best in Show, 2000; A Mighty Wind, 2003), is a very important trick that helps to create the documentary illusion: there is a sloppiness to the way people talk and carry themselves when they're genuinely not sure what they're going to say or have said to them that even the finest acting and directing can't exactly replicate. Besides, anyone who has seen a really great improv show can tell you, great improvisation is funny like almost nothing else in life, and while the fact of being put on film means that Spinal Tap can never have the feeling of danger that live improv does, it still has that energy and pacing.

Spinal Tap is, I contend, the most authentic of all faked documentaries: Reiner encouraged messy filmmaking style (people interacting with the film crew, deliberately awkward camera movements) that mimics the on-the-ground feel of a proper music doc, in a way that Guest's more polished affairs never entirely convince us that they're "real"; though by the same token, Reiner was more concerned with realism than Guest ever appears to be - for the latter filmmaker, the form is often just an excuse to allow his very talented ensemble to play around (indeed, Guest's last film with that ensemble, 2006's For Your Consideration, is made using almost exactly the same visual aesthetic, despite not in any way attempting to mimic the documentary form), while Reiner has a bit of social satire on his mind. Spinal Tap isn't just a comedy about idiot rockers behaving idiotically - though it's mostly that, and hilarious - it's also poking fun at Marty DiBergi himself, and about the fandom around a brand of music that the filmmakers obviously regard without any particular respect, and by aping the form of a documentary, Reiner and company are able to burst that fandom open from the inside, rather than mocking it from the outside. It is damned intelligent and merciless, in this regard, and frequently subtler than one quite knows what to do with.

What it's not, though, is cruel: though the filmmakers do not harbor any illusions that Spinal Tap is made up of intelligent or even morally upright people, they also don't delight in the suffering that the band undergoes (in this, Spinal Tap is also unlike the Guest films, which are much more overt in their sense of superiority over their casts; the one that has the most sympathy for its characters, A Mighty Wind, is also by a solid margin the least funny). Indeed, despite the plethora of gags predicated on the musicians' uncommon stupidity, the overwhelming feeling of the whole picture is of affection: it's actually sort of sad to watch the awareness that the tour is going terribly wrong worm its way into the group's bubble, and giddy and charming when they're able to pull happy ending out of the wreck of their lives. And despite how savagely the film consistently attacks metal's baked-in misogyny and adolescent infatuation with the mechanics of sex (e.g. "My baby fits me like a flesh tuxedo / I'd like to sink her with my pink torpedo"; or the band's desperate attempts to defend their lewd album cover) - and yet, it then dabbles in some truly obnoxious misogyny itself in the snotty depiction of David's girlfriend Jeanine (June Chadwick), the only really serious flaw in the whole movie - nobody who hated metal could possibly have written the invariably hilarious and frequently catchy songs of Spinal Tap's catalogue.

In fact, as good as it is as a comedy, This Is Spinal Tap is weirdly effective as a rock musical, too, effortlessly lampooning the dumbest cash-in music of three separate eras (the immeasurably lame Beatles knock-off "Give Me Some Money", unspeakably banal folk-rock warble "Listen to the Flower People", and of course the mercenary hair metal that makes up most of the soundtrack), and mocking the kind of bands that keep reinventing themselves in the most transparent, ineffective ways to keep up with the audience; but also providing enough genuinely fun songs that it's possible to understand how Spinal Tap could have clung to life for so long, and why DiBergi is so obsessed with them. It's maybe not enough to justify the weird pop culture byproduct of McKean, Guest and Shearer turning Spinal Tap into an actual touring band; but it's still awfully easy to hum along to every last one of the tunes here and only feel a little bit guilty for singing along, unironically, to the vapid lyrics.

So, the film is funny; it is fun; it is smart; it is structurally creative. It is, all in all, a great movie, disciplined and sharp and inventive, and it got Reiner's directorial career off to a great start, which he then turned into several other bright, well-constructed great movies, until all of a sudden he stopped. But let's not dwell on that, for it is depressing. Instead, let us appreciate the moment when Reiner joined forces with three of the finest comic performers of their generation, and the four of them together made one of the truly unique comedies in American cinema, a film which has aged far, far better than the moment in history which it so brilliantly encapsulated and deconstructed.

This Is Spinal Tap is ultimately a cult movie, but doesn't it feel wrong, somehow, to describe it that way? For it is one of those very special cult movies, like The Big Lebowski or The Rocky Horror Picture Show, that has also managed to colonise the mainstream without ever quite becoming a mainstream classic; it still, nearly thirty years after an initial release that found it tank at the box office, quite without special attention, feels odd and grubby and very much not like anything else that has been made in all the time since then. And this is maybe the difference between a cult classic that is fully absorbed into the wide body of pop culture versus one that remains willfully cultish: even though just about everyone probably recognises in at least a dim way the quote "these go up to eleven", as they do the idea of a rug tying the room together, or the sight of Tim Curry in fishnets and a corset, this has not been enough to domesticate the film. It is still not "normal", with its weird and experimental structure having been copied only a very few times since - the most prominent examples having been conceived and directed by one of its lead actors - and retaining a transgressive feeling of "wait, no, that's not how movies work" even after it's been long-canonised as one of the funniest American movies of the 1980s. I suppose this is a good thing: returning to Spinal Tap always brings with it a pronounced sense of discovery, a freshness that is uncommon with movies generally and unspeakably rare in a comedy, the genre most likely to wear thin after too much exposure and multiple viewings.

I could presume you know the film's hook, but at the risk of stating the obvious: Spinal Tap is presented as the work of indie documentarian Marty DiBergi (Rob Reiner, who also made his directorial debut with this feature), a huge fan of the British rock group Spinal Tap, who in 1982 were preparing their first American tour in six years. DiBergi, a fanboy if ever there was one, jumped on the chance to follow his rock gods around the country, and in doing so captured a snapshot of a rock group just about ready to collapse from exhaustion and malnutrition: singer David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean) and lead guitarist Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest) have been doing this for 17 years as the movie opens, and in that time have observed an initial burst of enthusiasm turn into almost complete obscurity, from which the group hopes to emerge by means of a particularly crude, sexually suggestive metal album titled Smell the Glove. The tour proves to be almost non-stop disasters, instigated in large part by the group's own colossal idiocy and venality, and by the time Spinal Tap reaches the west coast, St. Hubbins and Tufnel are just about ready to murder each other in frustration at the band's apparent dead-end trajectory.

Of course, what we have on our hands is the world's most prominent (though not its first) mockumentary, in which the visual language of non-fiction cinema is copied as precisely as possible in order to create the illusion that Spinal Tap, along with St. Hubbins, Tufnel, bassist Derek Smalls (Harry Shearer), and all their hangers-on actually existed. Reportedly, it even managed to trick some people way back in '84, though I cannot imagine how that is possible: it has writing and acting credits just like a normal scripted movie, though in point of fact much of the film was improvised around a narrative skeleton. And this, as Guest would prove with his own trio of improvised mockumentaries (Waiting for Guffman, 1996; Best in Show, 2000; A Mighty Wind, 2003), is a very important trick that helps to create the documentary illusion: there is a sloppiness to the way people talk and carry themselves when they're genuinely not sure what they're going to say or have said to them that even the finest acting and directing can't exactly replicate. Besides, anyone who has seen a really great improv show can tell you, great improvisation is funny like almost nothing else in life, and while the fact of being put on film means that Spinal Tap can never have the feeling of danger that live improv does, it still has that energy and pacing.

Spinal Tap is, I contend, the most authentic of all faked documentaries: Reiner encouraged messy filmmaking style (people interacting with the film crew, deliberately awkward camera movements) that mimics the on-the-ground feel of a proper music doc, in a way that Guest's more polished affairs never entirely convince us that they're "real"; though by the same token, Reiner was more concerned with realism than Guest ever appears to be - for the latter filmmaker, the form is often just an excuse to allow his very talented ensemble to play around (indeed, Guest's last film with that ensemble, 2006's For Your Consideration, is made using almost exactly the same visual aesthetic, despite not in any way attempting to mimic the documentary form), while Reiner has a bit of social satire on his mind. Spinal Tap isn't just a comedy about idiot rockers behaving idiotically - though it's mostly that, and hilarious - it's also poking fun at Marty DiBergi himself, and about the fandom around a brand of music that the filmmakers obviously regard without any particular respect, and by aping the form of a documentary, Reiner and company are able to burst that fandom open from the inside, rather than mocking it from the outside. It is damned intelligent and merciless, in this regard, and frequently subtler than one quite knows what to do with.

What it's not, though, is cruel: though the filmmakers do not harbor any illusions that Spinal Tap is made up of intelligent or even morally upright people, they also don't delight in the suffering that the band undergoes (in this, Spinal Tap is also unlike the Guest films, which are much more overt in their sense of superiority over their casts; the one that has the most sympathy for its characters, A Mighty Wind, is also by a solid margin the least funny). Indeed, despite the plethora of gags predicated on the musicians' uncommon stupidity, the overwhelming feeling of the whole picture is of affection: it's actually sort of sad to watch the awareness that the tour is going terribly wrong worm its way into the group's bubble, and giddy and charming when they're able to pull happy ending out of the wreck of their lives. And despite how savagely the film consistently attacks metal's baked-in misogyny and adolescent infatuation with the mechanics of sex (e.g. "My baby fits me like a flesh tuxedo / I'd like to sink her with my pink torpedo"; or the band's desperate attempts to defend their lewd album cover) - and yet, it then dabbles in some truly obnoxious misogyny itself in the snotty depiction of David's girlfriend Jeanine (June Chadwick), the only really serious flaw in the whole movie - nobody who hated metal could possibly have written the invariably hilarious and frequently catchy songs of Spinal Tap's catalogue.

In fact, as good as it is as a comedy, This Is Spinal Tap is weirdly effective as a rock musical, too, effortlessly lampooning the dumbest cash-in music of three separate eras (the immeasurably lame Beatles knock-off "Give Me Some Money", unspeakably banal folk-rock warble "Listen to the Flower People", and of course the mercenary hair metal that makes up most of the soundtrack), and mocking the kind of bands that keep reinventing themselves in the most transparent, ineffective ways to keep up with the audience; but also providing enough genuinely fun songs that it's possible to understand how Spinal Tap could have clung to life for so long, and why DiBergi is so obsessed with them. It's maybe not enough to justify the weird pop culture byproduct of McKean, Guest and Shearer turning Spinal Tap into an actual touring band; but it's still awfully easy to hum along to every last one of the tunes here and only feel a little bit guilty for singing along, unironically, to the vapid lyrics.

So, the film is funny; it is fun; it is smart; it is structurally creative. It is, all in all, a great movie, disciplined and sharp and inventive, and it got Reiner's directorial career off to a great start, which he then turned into several other bright, well-constructed great movies, until all of a sudden he stopped. But let's not dwell on that, for it is depressing. Instead, let us appreciate the moment when Reiner joined forces with three of the finest comic performers of their generation, and the four of them together made one of the truly unique comedies in American cinema, a film which has aged far, far better than the moment in history which it so brilliantly encapsulated and deconstructed.