Sparks Notes: Ah yes, I remember it well

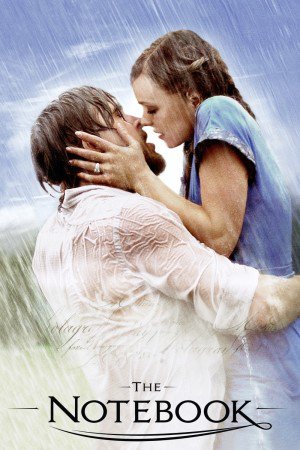

The Notebook is by most any objective standard the pinnacle of Nicholas Sparks adaptations. It made the most money, for one, which is almost certainly why it's the one that is almost always used in the ads for Sparks adaptations (i.e. "From the author of The Notebook"). It remains the best-reviewed by professional critics, and has the highest score from IMDb users, both of which reflect merely the fact that it is the best of them. It is with this film that Nicholas Sparks went from being a brand name among readers of frothy romantic tragedies to a brand name among moviegoers with an affection for such tragedies, and that's a much, much bigger pool, and I say that with all respect to habitual romance novelist readers (or habitual readers in general); and it is the film where Nicholas Sparks Movie knock-offs became a thing that people did. It is the film that turned 23-year-old Ryan Gosling and 25-year-old Rachel McAdams into relatively major actors, and if there was nothing else that The Notebook did other than raise the profile of these two kids from London, Ontario, it would have my eternal gratitude, both because they are terrific actors who I have come to love quite a lot since the film dropped in 2004, and because they are super damn pretty, and The Notebook shows them making out a lot.

The book, first published in 1996, was Sparks's first, and it has all the earmarks of a young writer finding his voice and laying down with more enthusiasm than artistry the thematic bedrock that would end up driving a whole boutique industry. Later, Sparks would dial down the enthusiasm, so as to make the lack of artistry less obvious. He'd also figure out a better way to tell stories: the very short novel is more of a sketch than a narrative proper, basically consisting of: 14 years ago, these two people loved one another, and now she's getting married but they meet up again and fall back in love, and it causes issues. Even in prose form, it feels awfully slight; onscreen it would be brutally insubstantial, if indeed it proved possible to dramatise it. And so writers Jan Sardi and Jeremy Leven added a whole lot of shit: making The Notebook the first Sparks adaptation in which the at times massive changes made to the source material actually improve it, unlike Message in a Bottle, where it just becomes more anodyne, or A Walk to Remember, where it becomes actively stupid. Mostly, the adaptation fleshes out that "14 years ago" part, only now it's just seven years; in the late 1930s in South Carolina, Noah Calhoun (Gosling) and Allie Hamilton (McAdams) meet as teenagers and fall in love and romanticise each other all out of propotion, right up until Allie's nasty, old-money mom Ann (Joan Allen) steps in and separates them. A distraught Noah writes letters every day until World War II breaks out, the whole war years sweep by in a montage, and the older, better-off Noah, now in possession of a beautiful old house in need of considerable repair, stumbles across Allie and her new fiancé, Lon Hammond (James Marsden); in return, she notes in the paper a story featuring his attempts to renovate the house, and in hardly any time they've reunited, only now they're much more confused and concerned about whether this time, they get to fix it, or if their lives have separated so much that there's just no hope.

There's also a framework narrative going on, and here I am stymied: it really seems like it's trying to for a twist ending, but I cannot imagine anybody not figuring out where things are going long, long before they get there. In the modern day (at least, modern as of 2004), a gentle old man, Duke (James Garner), who live in a nursing him, pulls out a notebook and reads to one of his fellow residents (Gena Rowlands), and that is exactly the story we hear. Occasionally, the film pulls back to remember that they're there (the book doesn't revisit them until the last chapter), and here's what I truly don't get - SPOILER, but not really - do we get, or do we not get, from the first scene, that it's Old Noah and Old Allie, except that Allie now has Alzheimer's and Noah is reminding her of their youth together as a means of reconnecting with a woman who doesn't even recognise him more than half the time, and reliving their love affair and subsequent life together for himself? Because from where I sit, that was pretty much obvious, and it's the only possible reason for the framework to exist at all; but the film does, in fact, seem to think that we have to be informed of that fact, and that it takes us aback when we are. Maybe I'm over-estimating the degree to which young Sparks had contempt for his readers, and we're supposed to figure it out all along.

Anyway, that framework provides The Notebook with its only really noteworthy break from cliché, which is to present geriatric love defying mental deterioration in a sweet and supportive light, and even there, it would have its ass handed to it a couple of years later by Away from Her. Otherwise, it's all tragic love affair and star-crossed lovers and so many self-conscious shots of sunsets and old buildings done in such a hushed, dusky style that it gets pretty much hilarious by about the 15-minute mark how unashamed cinematographer Robert Fraisse and director Nick Cassavetes are to do whatever is most obvious if it is what gets the information across with the least amount of creative effort.

On paper, it's just another damn soap operatic romantic melodrama, and yet I will confess something that makes me feel dirty: I didn't end up disliking it. And that has nothing to do with the cornball plot, and much to do with the people acting it out; if you ever want to see a flawless example of a movie which is redeemed from mediocrity solely through the cast, there is hardly a better one than this. Gosling, of course, is constitutionally incapable of giving a bad, or even a merely decent performance; and while he struggles with an attempt to maintain a Southern accent, there is not otherwise anything even a little bit wrong with his performance here, which moves with keen actorly insight from moments that he sells using with a boyish slyness to moments where he gets that doing anything other than standing there, being handsome, and letting the camera lust after him, would overload the movie with too much thoughtfulness that it isn't equipped for. McAdams works harder to less effect, in both cases because the movie simply isn't as interested in her: the target audience is women and the filmmakers are men, and in both cases that makes it easier to focus on Noah. But she's still awfully good, and also very easy on the eyes, and she does not struggle with a Southern accent, chiefly because she gives up almost immediately, in favor of simply burying her Canadian accent. Rowlands and Garner don't have nearly as many chances to show off, but they're both satisfactory as such things go, particularly Rowlands, who is simply too important an actress for a part as desperately simple and short as she gets here, but I imagine that being the mother of the director has something to do with it.

And it does turn out that being able to coerce the magnificent Gena Rowlands into classing up a role several hundred miles beneath her is the most important contribution that Cassavetes makes to the picture: but it's still not fair of me to say that the actors are solely responsible for the film being any good at all. Truth be told, the directing is better than competent: in particular, he rigorously maintains a more relaxed tone than the histrionics of the previous Sparks films, though composer Aaron Zigman tries very hard to ruin this; the only times that Cassavetes indulges in broad, heightened strokes, it is for punctuation of especially intense moments, which manages to give those moments extra emphasis (which is good), and make the rest of the movie a bit easier to watch without feeling pandered to (which is also good). It's not enough to make this a more intelligent and probing depiction of turbulent love than some of his father's work, for certain (John Cassavetes directing a Nicholas Sparks adaptation! I almost can't stand how fascinating that would be), but it gives the film enough of an individual personality that it stands out among all of the flimsy bottom-feeding tearjerkers that have done so much to spoil the grand name of romantic melodrama in the 21st Century.