Something to do with death

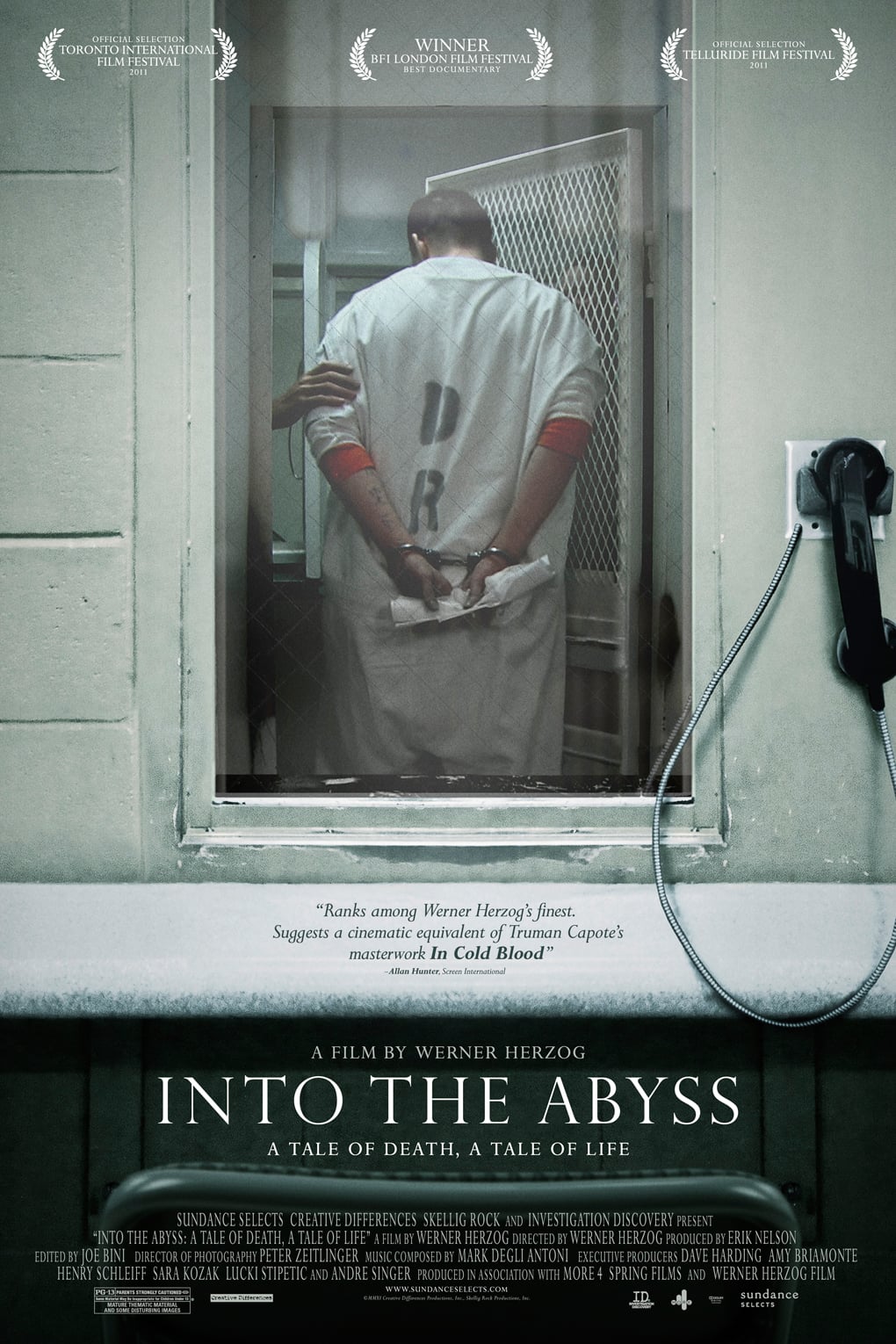

The subtitle of Werner Herzog's new documentary Into the Abyss declares itself to be "A tale of death, a tale of life", which is accurate-ish: it is about both of those things, but skewed rather heavily to the former for virtually the whole of its running time. Not in bad way - not in a bad way whatsoever, it results in one of the very best movies I've seen in 2011. Nor in a particularly depressing way - there's an intellectual remove through the whole thing that keeps the uniformly harrowing subject matter from ever becoming overwhelming. But in a terribly sober way, a hard-edged and bitterly dry way; the streak of impish humor that finds its way into virtually all of Herzog's films is banished, and for the first time in years, the director seems blissfully disinterested in self-consciously making "A Film By Werner Herzog", but instead in making just a film, the best one he can manage on the topic.

That topic is a 2001 triple homicide in Conroe, Texas, in which two young men, Michael Perry and Jason Burkett, shot a woman named Susan Stotler when their attempt to steal her red Camaro went slightly awry; later on, they also shot her sixteen-year-old son Adam and his friend, both acquaintances of the killers. Perry was executed in July, 2010, while Burkett is currently serving a prison sentence and will be up for parole in 2041; Herzog interviewed both of these men (Perry just eight days before his execution), as well as the survivors of the victims' families, the investigating officer on the case, Rev. Richard Lopez, the Death House chaplain, and Fred Allen, a retired officer who was the chief officer of the Death House, responsible for the successful prosecution of all executions at that facility, until he found himself shaken to his very soul by the high-profile case of Karla Faye Tucker. Other individuals with opinions worth examining come on and leave. The first part of the movie recaps the crime and subsequent investigation, leaving very little doubt as to Perry and Burkett's guilt; the rest is an exploration of what their lives are ten years later, and the lives of those their crime touched.

This is not a political statement about the desirability or not of the death penalty; Herzog states very early on that to him it is a simple matter, that there is no situation in which considers it appropriate for the government to decide that a person should die for their crimes, and that is the whole of his argument in that direction. What animates the film instead is it consideration of the whole stuff of death - the people who deal with it, the people who perpetrate it, the people who are left behind. It is remarkably free-form, given the level of editorial control Herzog frequently exercises over his projects - there is none of the thematic moralizing of a Grizzly Man nor the poetic flow of a Cave of Forgotten Dreams, just observing people in their opinions and beliefs. It is very much like Herzog's attempt at an Errol Morris documentary, and not just because it's in the same general ballpark as The Thin Blue Line; what it in fact reminded me of was Morris's debut Gates of Heaven (which was made at Herzog's urging), in that it gives a number of people their chance to have their say, some of whom the filmmaker plainly does not agree with - in one cutting moment, Herzog plainly states to Perry that he does not have to find the young man likable in any way to respect his status as a human being - but none of whom are ever mocked or otherwise treated ironically.

Through all of this, the film and filmmaker are trying to get around one of the trickiest questions in the whole of human existence: how do we live in the presence of death? For Perry and Burkett, it's by hedging and denying culpability. For Lisa Stotler-Balloun, daughter and sister to the victims, it's by burying herself in a depression that took years to clamber out of. For Burkett's new wife Melyssa, who married him after his incarceration and is pregnant with his child despite never having been physically intimate, it's by celebrating the creation of new life. The two best interview subjects are Allen, who relates his conversation to an anti-death penalty perspective in almost religious terms (each and every single interviewee, incidentally, proclaims that whatever suffering they have or shall undergone, it is all part of God's plan; one suspects that for Herzog, this is a dodge to get around the terrifying irrationality of living and dying, but he has the tact and sensibility to never once take his subjects to task, save for asking if Jesus would have supported capital punishment), and Burkett's father, Delbert, a prison lifer who is convinced that it's his fault that his son took such a wrong turn; both of these men have done a great deal of soul-searching in their lives and have the most poignant observations about the essential value of human life and dignity.

It would have been easy to turn this into an exploitation film of sorts; Herzog himself has done his fair share of just that in films like Grizzly Man and Little Dieter Needs to Fly. But a great deal of sensitivity and integrity was called for in this case, and that is exactly what the filmmaker brought to bear: though there is never doubting for a moment whose film this is - the way that he lets the camera rest with the characters without feeling as though he, like so many directors, is trying to make them uncomfortable to the point that they spill their guts is a particularly characteristic touch, as is the gentle way he pushes them to reflections that they might not have ever put quite that way with his idiosyncratic questions - it is also not a film in which Herzog is a constant editorial presence, just a truth-seeker. What truths he finds, if any, are hard to describe; Into the Abyss is more a film about the way that things feel than the way things physically are, and a film about how people exist rather than how people think. But the truths are there, and presented with a humanist respect for the people in the movie - all of them - that is both rare and heart-wrenching.

That topic is a 2001 triple homicide in Conroe, Texas, in which two young men, Michael Perry and Jason Burkett, shot a woman named Susan Stotler when their attempt to steal her red Camaro went slightly awry; later on, they also shot her sixteen-year-old son Adam and his friend, both acquaintances of the killers. Perry was executed in July, 2010, while Burkett is currently serving a prison sentence and will be up for parole in 2041; Herzog interviewed both of these men (Perry just eight days before his execution), as well as the survivors of the victims' families, the investigating officer on the case, Rev. Richard Lopez, the Death House chaplain, and Fred Allen, a retired officer who was the chief officer of the Death House, responsible for the successful prosecution of all executions at that facility, until he found himself shaken to his very soul by the high-profile case of Karla Faye Tucker. Other individuals with opinions worth examining come on and leave. The first part of the movie recaps the crime and subsequent investigation, leaving very little doubt as to Perry and Burkett's guilt; the rest is an exploration of what their lives are ten years later, and the lives of those their crime touched.

This is not a political statement about the desirability or not of the death penalty; Herzog states very early on that to him it is a simple matter, that there is no situation in which considers it appropriate for the government to decide that a person should die for their crimes, and that is the whole of his argument in that direction. What animates the film instead is it consideration of the whole stuff of death - the people who deal with it, the people who perpetrate it, the people who are left behind. It is remarkably free-form, given the level of editorial control Herzog frequently exercises over his projects - there is none of the thematic moralizing of a Grizzly Man nor the poetic flow of a Cave of Forgotten Dreams, just observing people in their opinions and beliefs. It is very much like Herzog's attempt at an Errol Morris documentary, and not just because it's in the same general ballpark as The Thin Blue Line; what it in fact reminded me of was Morris's debut Gates of Heaven (which was made at Herzog's urging), in that it gives a number of people their chance to have their say, some of whom the filmmaker plainly does not agree with - in one cutting moment, Herzog plainly states to Perry that he does not have to find the young man likable in any way to respect his status as a human being - but none of whom are ever mocked or otherwise treated ironically.

Through all of this, the film and filmmaker are trying to get around one of the trickiest questions in the whole of human existence: how do we live in the presence of death? For Perry and Burkett, it's by hedging and denying culpability. For Lisa Stotler-Balloun, daughter and sister to the victims, it's by burying herself in a depression that took years to clamber out of. For Burkett's new wife Melyssa, who married him after his incarceration and is pregnant with his child despite never having been physically intimate, it's by celebrating the creation of new life. The two best interview subjects are Allen, who relates his conversation to an anti-death penalty perspective in almost religious terms (each and every single interviewee, incidentally, proclaims that whatever suffering they have or shall undergone, it is all part of God's plan; one suspects that for Herzog, this is a dodge to get around the terrifying irrationality of living and dying, but he has the tact and sensibility to never once take his subjects to task, save for asking if Jesus would have supported capital punishment), and Burkett's father, Delbert, a prison lifer who is convinced that it's his fault that his son took such a wrong turn; both of these men have done a great deal of soul-searching in their lives and have the most poignant observations about the essential value of human life and dignity.

It would have been easy to turn this into an exploitation film of sorts; Herzog himself has done his fair share of just that in films like Grizzly Man and Little Dieter Needs to Fly. But a great deal of sensitivity and integrity was called for in this case, and that is exactly what the filmmaker brought to bear: though there is never doubting for a moment whose film this is - the way that he lets the camera rest with the characters without feeling as though he, like so many directors, is trying to make them uncomfortable to the point that they spill their guts is a particularly characteristic touch, as is the gentle way he pushes them to reflections that they might not have ever put quite that way with his idiosyncratic questions - it is also not a film in which Herzog is a constant editorial presence, just a truth-seeker. What truths he finds, if any, are hard to describe; Into the Abyss is more a film about the way that things feel than the way things physically are, and a film about how people exist rather than how people think. But the truths are there, and presented with a humanist respect for the people in the movie - all of them - that is both rare and heart-wrenching.