Right on the money

In 2002, the Oakland Athletics did not win the World Series. You might think that this is a sufficiently common event that it wouldn't be worth making a movie about it, but then there's Moneyball, which is happy to prove you wrong. You see, the A's didn't just fail to win the World Series - or make it very close to the World Series in the first place - they did so in a most unique and spectacular fashion, unsettling all of the given rules about how to accrue baseball players to a team, using the close analysis of statistics that have not, typically, been regarded as very interesting or significant. For baseball, as we know, is the most stats-heavy sport in America, and I should imagine in the whole wide world, and there's probably not a single element of a player's style that isn't quantified in some way by a decimal with three numbers after it.

Now, Moneyball is at heart a process story - I've not read Michael Lewis's book upon which the film is based, but certainly the career of Aaron Sorkin, one of two credited screenwriters (with Steven Zaillian; Stan Chervin, whoever he is, adapted the story), is rife with process stories, and is indeed full of nothing but process stories, if you want to look at it a certain way. And whether the process involved is television producing, website building, or military jurisprudence, they have a way of being about the personal conflicts involved rather than the actual subject matter. So just because Moneyball is nominally concerned with one of the most ungodly dense and alienating topics in life (apologies to the baseball stat nuts out there, but Christ, you even make us Oscar nerds look like dilettantes), it's not a movie that assumes the viewer really gives a shit about on-base percentages and so on, requiring only a working knowledge of how baseball functions - if you know the difference between a "walk" and a "hit", you're 90% of the way there - and spends the rest of the time looking with awe and admiration at the individuals involved in getting the A's from a reconstructing team without its three stars to a tie for the most wins of the season (and I don't want to give Sorkin too much credit for shaping a narrative with so many fingers in it, but this much at least is true: it's alarmingly, even distractingly easy to tell which parts were written by Sorkin and which by Zaillian).

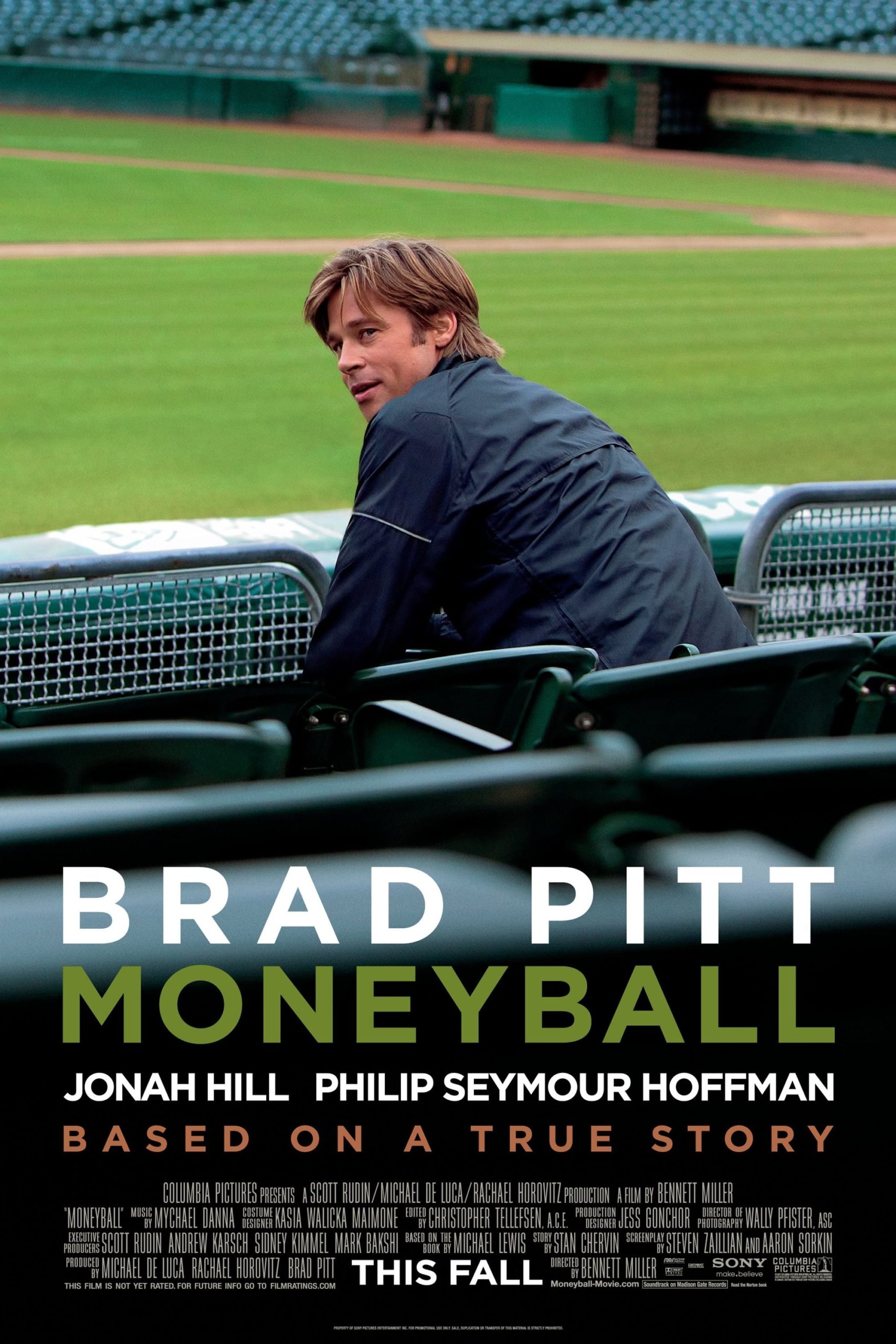

In the film's eyes, this is primarily the story of Billy Beane (Brad Pitt), Oakland's general manager and decent everyday fella with a little hint of a family problem (he has an ex-wife and a rather too-sweet daughter), who realises that The Way Things Are isn't working out well for a baseball team too damn poor to afford any decent players, with those bullies the New York Yankees throwing around cash like drunk frat boys (the movie does an outstanding job of tricking us into liking the A's from before its first shot: it opens with a title card comparing the total dollar amount spent by the Yankees and the Athletics, and from that second, every viewer who fucking hates the Yankees - which is to say, every viewer who doesn't live in New York and some of those who do - has instantly been connived into rooting for the Little Team That Could). Billy finds an ally in the form of composite character Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), a 26-year-old with an econ degree who has figured out a system of getting the most wins per dollar spent on players using an entirely different set of criteria than baseball talent scouts have been using since time immemorial. This particularly appeals to Billy, on account of his *wavy lines* Tormented History, in which those awful scouts managed to convince him that he was fated to be an all-time great player, and when it didn't pan out, wrote him off as just one of those missteps that happens every season*wavy lines*. Of course, this kind of unorthodox thinking is opposed by the forces of tradition, as represented by pretty much everybody else in film, but especially team manager Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman), and Billy and Peter become, not just baseball executives, but messiahs of a new way of thinking.

It pretty much writes itself, though if this were a work of fiction, Oakland would have won the Series, or at least made it more than one round into the playoffs. But no matter: as Sorkin and Zaillian and Chervin handle it, this is very much a movie about Billy coming to terms with his demons, and proving that his whole life hasn't been one long fuck-up. Win or lose, baseball is the yardstick by which Billy's personality is measured, but little more: even the absolutely crackerjack scenes of him prattling along with other GMs, trading baseball players like they were baseball cards, is ultimately more about his drive than they are about assembling a baseball team, even as they are very much the most entertaining inside bas scenes about the arcana of the subject matter in the film.

The movie relies on Pitt, in other words, to a potentially ruinous degree, but the actor-producer brings his A-game; I'm too fond of what he did in Inglourious Basterds, The Assassination of Jesse James... and especially Burn After Reading to come anywhere near the "his best performance in years!" train that so many folks seem to be riding, but it's damn good work, and one of the most fascinating star turns of the year: while at all points we are aware that we're watching Brad Pitt, and that the reason we like Billy Beane so much and don't mind that the movie is playing with a stacked deck to make sure that he seems as much like a saint and martyr as possible is because Brad Pitt is playing him, there's never really a moment at which the actor relies on being Brad Pitt, as he did even in some of his very best performances. It's not invisible, he doesn't "disappear" into Billy Beane, he just... stops being Brad Pitt, I guess.

Everything around him is achingly simple: Bennett Miller, making his sophomore feature six years after Capote, has not significantly changed his aesthetic since that movie: he's still refusing to adopt a personal style and stay out of the way of the script and performances, which only really hurts the movie in a swollen running time that sags here and there, but not as badly as it could have. Wally Pfister makes a rare trip outside of Christopher Nolan's neighborhood to make something that's handsome without being pretty or indulgently romantic (the latter sin being terribly common in baseball pictures), and that's about as far as craft goes.

It's a simple film, basically - a nice crowd-pleaser that the adults out there get to enjoy without feeling pandered to, but not nearly smart enough to be that ever elusive Film For Adults. It's this year's The Blind Side without the dubious sociology; it wants to make you feel nice, and it largely does so, without saying anything much about humanity, the world, and especially not the sport of baseball, but that topic, I fear, is for a different kind of geek than I to attack.

Now, Moneyball is at heart a process story - I've not read Michael Lewis's book upon which the film is based, but certainly the career of Aaron Sorkin, one of two credited screenwriters (with Steven Zaillian; Stan Chervin, whoever he is, adapted the story), is rife with process stories, and is indeed full of nothing but process stories, if you want to look at it a certain way. And whether the process involved is television producing, website building, or military jurisprudence, they have a way of being about the personal conflicts involved rather than the actual subject matter. So just because Moneyball is nominally concerned with one of the most ungodly dense and alienating topics in life (apologies to the baseball stat nuts out there, but Christ, you even make us Oscar nerds look like dilettantes), it's not a movie that assumes the viewer really gives a shit about on-base percentages and so on, requiring only a working knowledge of how baseball functions - if you know the difference between a "walk" and a "hit", you're 90% of the way there - and spends the rest of the time looking with awe and admiration at the individuals involved in getting the A's from a reconstructing team without its three stars to a tie for the most wins of the season (and I don't want to give Sorkin too much credit for shaping a narrative with so many fingers in it, but this much at least is true: it's alarmingly, even distractingly easy to tell which parts were written by Sorkin and which by Zaillian).

In the film's eyes, this is primarily the story of Billy Beane (Brad Pitt), Oakland's general manager and decent everyday fella with a little hint of a family problem (he has an ex-wife and a rather too-sweet daughter), who realises that The Way Things Are isn't working out well for a baseball team too damn poor to afford any decent players, with those bullies the New York Yankees throwing around cash like drunk frat boys (the movie does an outstanding job of tricking us into liking the A's from before its first shot: it opens with a title card comparing the total dollar amount spent by the Yankees and the Athletics, and from that second, every viewer who fucking hates the Yankees - which is to say, every viewer who doesn't live in New York and some of those who do - has instantly been connived into rooting for the Little Team That Could). Billy finds an ally in the form of composite character Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), a 26-year-old with an econ degree who has figured out a system of getting the most wins per dollar spent on players using an entirely different set of criteria than baseball talent scouts have been using since time immemorial. This particularly appeals to Billy, on account of his *wavy lines* Tormented History, in which those awful scouts managed to convince him that he was fated to be an all-time great player, and when it didn't pan out, wrote him off as just one of those missteps that happens every season*wavy lines*. Of course, this kind of unorthodox thinking is opposed by the forces of tradition, as represented by pretty much everybody else in film, but especially team manager Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman), and Billy and Peter become, not just baseball executives, but messiahs of a new way of thinking.

It pretty much writes itself, though if this were a work of fiction, Oakland would have won the Series, or at least made it more than one round into the playoffs. But no matter: as Sorkin and Zaillian and Chervin handle it, this is very much a movie about Billy coming to terms with his demons, and proving that his whole life hasn't been one long fuck-up. Win or lose, baseball is the yardstick by which Billy's personality is measured, but little more: even the absolutely crackerjack scenes of him prattling along with other GMs, trading baseball players like they were baseball cards, is ultimately more about his drive than they are about assembling a baseball team, even as they are very much the most entertaining inside bas scenes about the arcana of the subject matter in the film.

The movie relies on Pitt, in other words, to a potentially ruinous degree, but the actor-producer brings his A-game; I'm too fond of what he did in Inglourious Basterds, The Assassination of Jesse James... and especially Burn After Reading to come anywhere near the "his best performance in years!" train that so many folks seem to be riding, but it's damn good work, and one of the most fascinating star turns of the year: while at all points we are aware that we're watching Brad Pitt, and that the reason we like Billy Beane so much and don't mind that the movie is playing with a stacked deck to make sure that he seems as much like a saint and martyr as possible is because Brad Pitt is playing him, there's never really a moment at which the actor relies on being Brad Pitt, as he did even in some of his very best performances. It's not invisible, he doesn't "disappear" into Billy Beane, he just... stops being Brad Pitt, I guess.

Everything around him is achingly simple: Bennett Miller, making his sophomore feature six years after Capote, has not significantly changed his aesthetic since that movie: he's still refusing to adopt a personal style and stay out of the way of the script and performances, which only really hurts the movie in a swollen running time that sags here and there, but not as badly as it could have. Wally Pfister makes a rare trip outside of Christopher Nolan's neighborhood to make something that's handsome without being pretty or indulgently romantic (the latter sin being terribly common in baseball pictures), and that's about as far as craft goes.

It's a simple film, basically - a nice crowd-pleaser that the adults out there get to enjoy without feeling pandered to, but not nearly smart enough to be that ever elusive Film For Adults. It's this year's The Blind Side without the dubious sociology; it wants to make you feel nice, and it largely does so, without saying anything much about humanity, the world, and especially not the sport of baseball, but that topic, I fear, is for a different kind of geek than I to attack.