Blockbuster History: Creepy houses

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: movies about rattly old houses that may or may not host an assortment of disturbed ghosts or other paranormal nasties, including the new Don't Be Afraid of the Dark haven't been a truly in vogue since the 1930s. At the same time, it's a horror subgenre that absolutely refuses to die, and when it works, there's nothing better; so it is that I'm taking this opportunity to finally write a review of just such a movie, in my opinion one of the scariest things ever made.

There are two lines of thought that dominate any discussion of what makes a movie scary: either it is a great deal of subtlety and implication that allows the viewer to imagine all sorts of terrible things just out of sight, or it is being explicit in the most hideous, disconcerting way possible. It is the difference between a creepy ghost story and a bloody slasher flick; I think it's not an undue generalisation to suggest that the side any given person comes down on is going to be reflected in their age. As recently as 1999, the battle between these two poles flared up (though it wasn't really defined that way that I know of) when The Blair Witch Project divided people into the "it's outstanding because it's completely vague about everything" and the "ferchrissake, it's a handful of sticks" camps (also the "this movie is amateurish and stupid" camp, but let's not dwell on them), but for the most part, subtlety has long since lost, following the loosening of standards over the course of the last four decades, especially the eruption of hyper-violent horror movies in the 1970s and what followed.

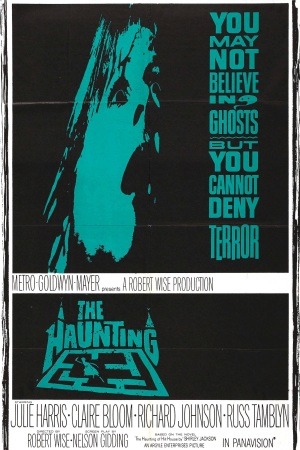

For those who prefer their scary movies heavy on the atmosphere and the slow boil and light on the gory monsters and screaming teenagers - and I guess I fall mostly into that category, even though two of my three favorite American horror films are the decidedly explicit Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Shining (the third, just so there's no confusion, is our current subject) - one of the most reliable standards to bear has been 1963's The Haunting, adapted from Shirley Jackson's novel The Haunting of Hill House: read any positive review of the film, and nine times in ten they'll spend at least a little bit of energy praising its exemplary restraint. I am not prepared to break with this tradition, though it seems to me that any film that uses ghastly threatening shadows and production design that suggests a collaboration between E.M. Forster and H.P. Lovecraft with the reckless abandon of The Haunting can't be fairly said to be restraining itself, so much as refraining from explicit violence.

Anyway, I bring this up mostly because it seemed dishonest to try to write about The Haunting without observing that it serves as a symbol of an extinct style of horror filmmaking to so many people. But really, the style of The Haunting was never terribly widespread to begin with: truly great movies by definition can't also be typical, and The Haunting is at least truly great. Borderline perfect, I'd say myself, and not just because it's one of the few movies that scared me so much that it ever gave me a sleepless night. Strip away all of its frightening elements, and the film remains a sophisticated, complex, and tremendously subtle (there's that damn word!) character study: I would say easily the best work in director Robert Wise's career, if not for the presence The Day the Earth Stood Still complicating things. As it is, anyone who best knows him for making the handsome, but indefinitely hollow Broadway adaptations West Side Story and The Sound of Music certainly wouldn't expect that he had this kind of brooding Gothic elegance in him, right square in between those Oscar-winning megaliths.

We enter the film by means of an oddly chummy narration provided by an Englishman whose identity we don't know: he recites for us the history of Hill House, a gargantuan 90-year-old mansion in hidden away in a corner of New England. From the moment of the house's completion, it has been the site of death and misery, all involving the family of the wealthy and, it would appear, beastly Hugh Crain (Howard Lang); and that is why, the narrator concludes, he wants to go there to study it. For our Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson) is a researcher in the paranormal, and he has heard many enticing stories about the dark psychic energies infesting Hill House.

He arranges for several people to join him, all of them known to have significant psychic events in their past: but in the end, only two show up. One of these is a woman who only goes by Theodora (Claire Bloom), and her ESP is the strongest that has ever been studied by parapsychologists. The other is Eleanor Lance (Julie Harris), whose own psychic past was so upsetting that she has repressed it, or at least redefined what happened to her back when she was a child. In the meantime, her interest in Markway's experiment is much more earthly: her invalid mother has just died, bringing to a close 15 years of nursemaiding that have devoured Eleanor's adult life. She's presently living on the couch of her sister and brother-in-law, and is desperate for anything remotely new or exciting to color her painfully dull life. Along for the ride as well is Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn, of West Side Story), nephew to Hill House's present owner and heir apparent to the property; he doesn't believe in ghosts at all, but he does have a keen interest in assessing the value of the building.

I refuse to give away any more of the plot than that, on the grounds that anyone who hasn't seen the film deserves better than to have me give away any of the details. It's worth letting the shocks that happen to the characters come as a shock to the viewer as well, though this much isn't a spoiler: The Haunting is emphatically not one of those haunted house movies where it turns out to have been a con by an unscrupulous crook all along. What exists in Hill House, if it is not necessarily ghosts in the normal sense of that word, is anyway not human.

Admittedly, saying with objective certainty that something "is scary" is almost as impossible as defining what is funny, but at least this much has to be conceded: Wise and his crew do their very damnedest to make The Haunting scary. There is first the matter of Hill House itself: designed by Elliot Scott and decorated by John Jarvis, it is about as compelling wrong as any haunted house in any movie could be. We are told that there is not a single square corner in the building; later the characters assert that something in the very bones of the building is fundamentally warped and evil, and based on the evidence of our eyes, both of these contentions seem entirely reasonable. It's in everything from the big details, such as the dark wood that sucks all the energy out of everything, and the clashing architectural styles on display throughout, down to the littlest touches of a creepy angel statue here, an incredible unpleasant wallpaper there, or the incidental detail, off in one corner of the frame but hard to miss, in the very nursery that is the heart of all the suffering in the house, where the cruelly religious Crain emblazoned the legend "Suffer little children" over his daughter's doorway.

This is shot by Davis Boulton with lighting straight out of film noir, using shadows to bring out the horrible textures of the place, the boosted contrast making everything seem hard and edgy; he and Wise further use camera movements that lurch about and look at things from grotesquely canted angles and switch from subjective to objective viewpoints with no warning. I do wish that it hadn't been shot in anamorphic Panavision; the filmmakers are mostly at a loss what to do with the wide frame. But that is my only real complaint against the film.

Into these creepy, uncanny, disorienting visuals, comes one of the finest sound mixes in cinema: indeed, as important as the visuals are to The Haunting, it's the soundtrack that actually makes the movie scary. The big showstopping scene that is probably the most famous bit of the whole film is made up of almost nothing but a knocking sound and the heavy breathing of Eleanor and Theo: and while the close-ups and insert shots in the scene help, I don't half wonder if it would be almost as effective with the picture turned off.

So what we have is a well-shot, good sounding haunted house movie, and it scares the bejeezus out of many people, including your humble blogger. But that is, as things go, kind of a shallow reason for conferring masterpiece status onto a film. What gives The Haunting that extra push is that in addition to being the best-made haunted house movie of all time, it's also one of the greatest psychological thrillers, creating in Eleanor Lance a tremendous character, an woman who was barely out of her teens when she was obliged to become her mother's caretaker, and has emerged from that job with a healthy sense of resentment that she refuses to acknowledge, and it at once sex-starved and sex-phobic, a perfectly amazing mess of neurotic impulses. Her sweetly pathetic attempts to flirt with Markway - motivated, presumably, not because he is a handsome man but because he's the first one who has ever really communicated with her - is one thing, but her relationship with Theo, strongly implied to be a lesbian, is stunningly off-kilter: here Eleanor is clinging to her and lying in bed with her, desperate for comfort and an adult woman to baby her; here she is screeching at her friend and calling her unnatural and filthy.

Eleanor is, in short, a broken and fragile and at times incredibly nasty person - in her fight with her sister, it's not terribly hard to agree that she's in the wrong while finding her disgustingly passive-aggressive* - and her descent into madness and possession, helpfully marked out by a constant stream of narration that becomes harder and harder to parse into anything rational as the movie goes on, is every bit as terrifying as the malevolence of Hill House. More so, because it's real: and yet the ultimate brilliance of The Haunting is that it collapses the distinction between paranormal horror and psychological horror, that a character study this intense is exactly cotangent with such a deliciously goosebumpy ghost story. The house wants a victim, and it chooses her because she is too weak in her self-identity to resist; at the same time, the ghastly happenings are a metaphor for, and extension of, Eleanor's internal disintegration. Only The Shining has ever matched the accomplishment in this film of binding those two strains together so tightly, and as fun as it is to watch Jack Nicholson go overboard in that movie, he's not doing anything as nuanced and fine as Harris - the most Tony'd actor in stage history - does in every scene of this film, balancing sex, childishness, irrational matricidal guilt, mortal fear, and the enthusiasm of an adventurous tourist constantly, in a ever-shifting war for dominance. It's too easy to say they don't make 'em like this anymore: in fact, they never really did. This kind of all-round excellence is a bolt of lightning, not a generational marker, and The Haunting is an exemplary, stand-out work regardless of its era.

*Shortly after, she thinks to herself while driving about how her family will react when they find she's missing in a scene irresistibly reminiscent of Psycho and that other great amoral victim of '60s horror, Marion Crane.

There are two lines of thought that dominate any discussion of what makes a movie scary: either it is a great deal of subtlety and implication that allows the viewer to imagine all sorts of terrible things just out of sight, or it is being explicit in the most hideous, disconcerting way possible. It is the difference between a creepy ghost story and a bloody slasher flick; I think it's not an undue generalisation to suggest that the side any given person comes down on is going to be reflected in their age. As recently as 1999, the battle between these two poles flared up (though it wasn't really defined that way that I know of) when The Blair Witch Project divided people into the "it's outstanding because it's completely vague about everything" and the "ferchrissake, it's a handful of sticks" camps (also the "this movie is amateurish and stupid" camp, but let's not dwell on them), but for the most part, subtlety has long since lost, following the loosening of standards over the course of the last four decades, especially the eruption of hyper-violent horror movies in the 1970s and what followed.

For those who prefer their scary movies heavy on the atmosphere and the slow boil and light on the gory monsters and screaming teenagers - and I guess I fall mostly into that category, even though two of my three favorite American horror films are the decidedly explicit Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Shining (the third, just so there's no confusion, is our current subject) - one of the most reliable standards to bear has been 1963's The Haunting, adapted from Shirley Jackson's novel The Haunting of Hill House: read any positive review of the film, and nine times in ten they'll spend at least a little bit of energy praising its exemplary restraint. I am not prepared to break with this tradition, though it seems to me that any film that uses ghastly threatening shadows and production design that suggests a collaboration between E.M. Forster and H.P. Lovecraft with the reckless abandon of The Haunting can't be fairly said to be restraining itself, so much as refraining from explicit violence.

Anyway, I bring this up mostly because it seemed dishonest to try to write about The Haunting without observing that it serves as a symbol of an extinct style of horror filmmaking to so many people. But really, the style of The Haunting was never terribly widespread to begin with: truly great movies by definition can't also be typical, and The Haunting is at least truly great. Borderline perfect, I'd say myself, and not just because it's one of the few movies that scared me so much that it ever gave me a sleepless night. Strip away all of its frightening elements, and the film remains a sophisticated, complex, and tremendously subtle (there's that damn word!) character study: I would say easily the best work in director Robert Wise's career, if not for the presence The Day the Earth Stood Still complicating things. As it is, anyone who best knows him for making the handsome, but indefinitely hollow Broadway adaptations West Side Story and The Sound of Music certainly wouldn't expect that he had this kind of brooding Gothic elegance in him, right square in between those Oscar-winning megaliths.

We enter the film by means of an oddly chummy narration provided by an Englishman whose identity we don't know: he recites for us the history of Hill House, a gargantuan 90-year-old mansion in hidden away in a corner of New England. From the moment of the house's completion, it has been the site of death and misery, all involving the family of the wealthy and, it would appear, beastly Hugh Crain (Howard Lang); and that is why, the narrator concludes, he wants to go there to study it. For our Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson) is a researcher in the paranormal, and he has heard many enticing stories about the dark psychic energies infesting Hill House.

He arranges for several people to join him, all of them known to have significant psychic events in their past: but in the end, only two show up. One of these is a woman who only goes by Theodora (Claire Bloom), and her ESP is the strongest that has ever been studied by parapsychologists. The other is Eleanor Lance (Julie Harris), whose own psychic past was so upsetting that she has repressed it, or at least redefined what happened to her back when she was a child. In the meantime, her interest in Markway's experiment is much more earthly: her invalid mother has just died, bringing to a close 15 years of nursemaiding that have devoured Eleanor's adult life. She's presently living on the couch of her sister and brother-in-law, and is desperate for anything remotely new or exciting to color her painfully dull life. Along for the ride as well is Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn, of West Side Story), nephew to Hill House's present owner and heir apparent to the property; he doesn't believe in ghosts at all, but he does have a keen interest in assessing the value of the building.

I refuse to give away any more of the plot than that, on the grounds that anyone who hasn't seen the film deserves better than to have me give away any of the details. It's worth letting the shocks that happen to the characters come as a shock to the viewer as well, though this much isn't a spoiler: The Haunting is emphatically not one of those haunted house movies where it turns out to have been a con by an unscrupulous crook all along. What exists in Hill House, if it is not necessarily ghosts in the normal sense of that word, is anyway not human.

Admittedly, saying with objective certainty that something "is scary" is almost as impossible as defining what is funny, but at least this much has to be conceded: Wise and his crew do their very damnedest to make The Haunting scary. There is first the matter of Hill House itself: designed by Elliot Scott and decorated by John Jarvis, it is about as compelling wrong as any haunted house in any movie could be. We are told that there is not a single square corner in the building; later the characters assert that something in the very bones of the building is fundamentally warped and evil, and based on the evidence of our eyes, both of these contentions seem entirely reasonable. It's in everything from the big details, such as the dark wood that sucks all the energy out of everything, and the clashing architectural styles on display throughout, down to the littlest touches of a creepy angel statue here, an incredible unpleasant wallpaper there, or the incidental detail, off in one corner of the frame but hard to miss, in the very nursery that is the heart of all the suffering in the house, where the cruelly religious Crain emblazoned the legend "Suffer little children" over his daughter's doorway.

This is shot by Davis Boulton with lighting straight out of film noir, using shadows to bring out the horrible textures of the place, the boosted contrast making everything seem hard and edgy; he and Wise further use camera movements that lurch about and look at things from grotesquely canted angles and switch from subjective to objective viewpoints with no warning. I do wish that it hadn't been shot in anamorphic Panavision; the filmmakers are mostly at a loss what to do with the wide frame. But that is my only real complaint against the film.

Into these creepy, uncanny, disorienting visuals, comes one of the finest sound mixes in cinema: indeed, as important as the visuals are to The Haunting, it's the soundtrack that actually makes the movie scary. The big showstopping scene that is probably the most famous bit of the whole film is made up of almost nothing but a knocking sound and the heavy breathing of Eleanor and Theo: and while the close-ups and insert shots in the scene help, I don't half wonder if it would be almost as effective with the picture turned off.

So what we have is a well-shot, good sounding haunted house movie, and it scares the bejeezus out of many people, including your humble blogger. But that is, as things go, kind of a shallow reason for conferring masterpiece status onto a film. What gives The Haunting that extra push is that in addition to being the best-made haunted house movie of all time, it's also one of the greatest psychological thrillers, creating in Eleanor Lance a tremendous character, an woman who was barely out of her teens when she was obliged to become her mother's caretaker, and has emerged from that job with a healthy sense of resentment that she refuses to acknowledge, and it at once sex-starved and sex-phobic, a perfectly amazing mess of neurotic impulses. Her sweetly pathetic attempts to flirt with Markway - motivated, presumably, not because he is a handsome man but because he's the first one who has ever really communicated with her - is one thing, but her relationship with Theo, strongly implied to be a lesbian, is stunningly off-kilter: here Eleanor is clinging to her and lying in bed with her, desperate for comfort and an adult woman to baby her; here she is screeching at her friend and calling her unnatural and filthy.

Eleanor is, in short, a broken and fragile and at times incredibly nasty person - in her fight with her sister, it's not terribly hard to agree that she's in the wrong while finding her disgustingly passive-aggressive* - and her descent into madness and possession, helpfully marked out by a constant stream of narration that becomes harder and harder to parse into anything rational as the movie goes on, is every bit as terrifying as the malevolence of Hill House. More so, because it's real: and yet the ultimate brilliance of The Haunting is that it collapses the distinction between paranormal horror and psychological horror, that a character study this intense is exactly cotangent with such a deliciously goosebumpy ghost story. The house wants a victim, and it chooses her because she is too weak in her self-identity to resist; at the same time, the ghastly happenings are a metaphor for, and extension of, Eleanor's internal disintegration. Only The Shining has ever matched the accomplishment in this film of binding those two strains together so tightly, and as fun as it is to watch Jack Nicholson go overboard in that movie, he's not doing anything as nuanced and fine as Harris - the most Tony'd actor in stage history - does in every scene of this film, balancing sex, childishness, irrational matricidal guilt, mortal fear, and the enthusiasm of an adventurous tourist constantly, in a ever-shifting war for dominance. It's too easy to say they don't make 'em like this anymore: in fact, they never really did. This kind of all-round excellence is a bolt of lightning, not a generational marker, and The Haunting is an exemplary, stand-out work regardless of its era.

*Shortly after, she thinks to herself while driving about how her family will react when they find she's missing in a scene irresistibly reminiscent of Psycho and that other great amoral victim of '60s horror, Marion Crane.