Blockbuster History: Talking to the animals

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Kevin James gets to pretend he's Ben Stiller's character in Night at the Museum in the singularly bleak-looking Zookeeper. It is but the latest in a long, miserably chain of family movies in which state-of-the-art visual effects allow filmmakers to do terrible things with animals. I should perhaps have gone with the original film of which today's subject is a remake, but that is not a movie that anyone should be obliged to watch twice.

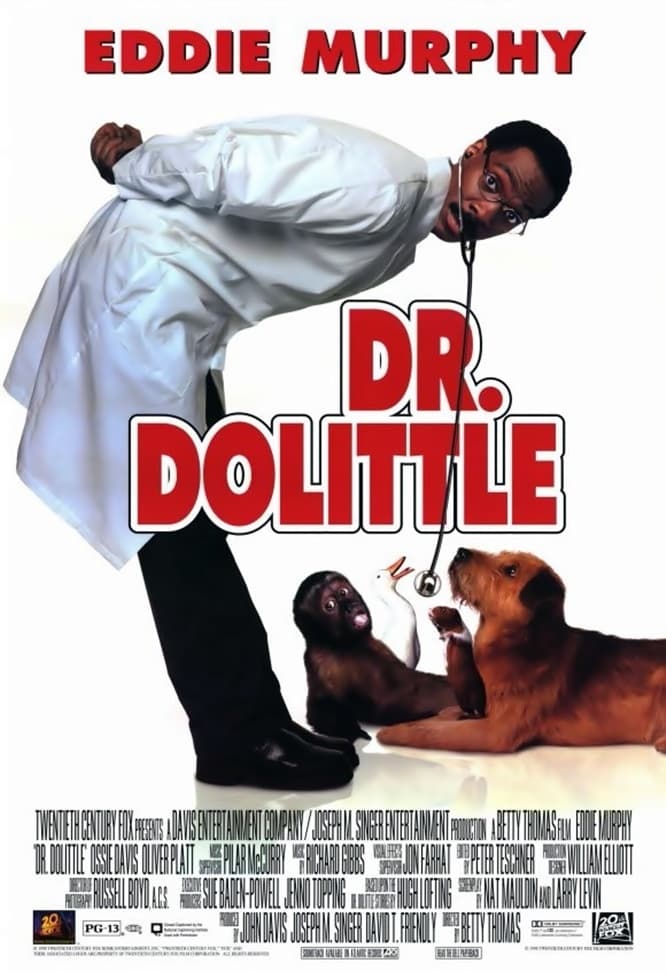

Doctor Dolittle, 1967 edition, and Dr. Dolittle, 1998 edition, are more noteworthy for their differences than their similarities: the former is a lumbering behemoth of a musical closely based on the children's stories by author Hugh Lofting of an eccentric Victorian animal lover, the latter takes little from Lofting other than the name, taking place instead in contemporaneous San Francisco. The original is a genteel fable, the remake a broad comedy. Both films are extremely bad, but only the first one was able to snag a nomination for the Best Picture Oscar (and eight others besides; it won two), thereby becoming the easy answer to the question, "What is the worst movie ever nominated for a Best Picture Oscar?"

What divides the movies most of all, however, is the approach they take the central concept, talking to the animals. In 1967, a dapper and visibly unhappy Rex Harrison simply chatted at real-live critters, and informed the humans around him as to what they were saying. The grand advances in technology meant that 31 years later, Eddie Murphy, who very well might have been unhappy, but by that point in his career had probably gotten to used to it, and undoubtedly cried himself to sleep on piles of $100 bills, not only spoke to an assortment of dogs, cats, birds, and so on and so forth; they talked right back to him, in the voices of celebrities who may or may not have taken the job to make something their kids could watch, and more likely did it because they could make a couple hundred grand just by sitting on the phone for 30 minutes. This was before everything in the world was CGI, so the bulk of the animals, though not all of them, were achieved practically, by the technical geniuses at the Jim Henson Creature Shop, and that at least is a blessing: a decade and change later, and this movie would look like Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore.

To understand why the Doctor Dolittle evolution took place, it is instructive to take a look at the world back in 1998. Two things had happened shortly prior to the remake's release that made it, or at least something exactly like it under a different title, all but inevitable. The first was that in the summer of 1995, two talking pig movies were released: the earlier one, Gordy, did very little but to prime the pump for the subsequent Babe, one of the great children's films ever made, for so many reasons, but surely not the least of them is the tremendous quality of the talking animal effects by... the Jim Henson Creature Shop. Babe was a hit, an Academy Award nominee, and a critical darling, and while the unspeakable glut of movies with sassy talking animals wouldn't really ignite until computers put such beasts in the hands of even the shallowest filmmakers, it was in 1995 that the genre began its upwards ascent.

The second thing happened a year later, when a comic star whose career to that point consisted almost entirely of R-rated movies took a gamble on, well, not exactly a family film: it was PG-13 and pretty damn filthy in points. But still, when Eddie Murphy starred in ><>The Nutty Professor, the result was his highest-grossing vehicle since the epochal Beverly Hills Cop II nine years prior, and a film that turned the raunchy funnyman, overnight, into the warm and fuzzy star of any goddamn kiddie picture he could get his hands on, a man who seemingly overnight decided that the only thing he wanted was to cash huge paychecks from starring in gigantic, empty-headed comedies propped up by visual effects and high-concept flim-flam. And before you can say, "you got your anodine juvenile comedy peanut butter in my pop-culture besotted animal-driven kiddie flick", Dr. Dolittle was born, the bastard son of a thousand maniacs.

Insofar as the film's plot was ever novel, that novelty has been seriously compromised by the fact that it's basically the exact same story of every subsequent Murphy vehicle: John Dolittle was once a wide-eyed child who didn't think it was a big deal that he could talk to animals until his dad (Ossie Davis) shamed him into hiding his gift; a great many years later, Dolittle has become a soulless, hateful, wisecracking robot of capitalism, treating his wife (Kristen Wilson) and daughters (Raven-Symoné and Kyla Pratt) with icy indifference, and preparing to send his darling little community health center right up Shit Creek by selling it to a merciless industrial health care CEO (Peter Boyle), and in all possible ways being exactly ready for a life-changing event that will ready him up to be a decent human being and family man. The life-changing event in question is a car accident that leaves him with a bump on the head that re-awakens his dormant gift, when the snotty dog he just hits calls him a bonehead in the dulcet tones of Norm MacDonald.

A great deal of talking-animal buffonery ensues: Dolittle takes his family to a woodland cabin, and word gets out to all the forest creatures that a man who understands their speech and has medical training is nearby; in hardly any time, the doctor has been overwhelmed by sick and hypochondriac animals. Back in San Francisco, he endures the constant barbs of the dog, Lucky, and his younger daughter's guinea pig, Rodney (Chris Rock), while also falling in with a suicidal tiger named Jacob (Albert Brooks). It's good for the film that it's target audience is six-year-olds, since they are the only ones who won't be able to guess where all of this is going (Dolittle acts crazy and it endangers the deal, then he pulls his shit together and saves the day, and tells the big corporate dude that he doesn't want to sell after all), though by the same token, I am unsure that I'd want to let a six-year-old be confronted with some of the jokes, primarily those involving an impotent pigeon (Garry Shandling), or the bit where the tiger is referred to as a pussy. But heck, them's the breaks with joyless pop-culture addicted kids' films, and at least the film was made early enough that it managed largely escape the black hole of shit jokes that most children's entertainment has since become.

Back in 1998, the spectacle of famous actors playing characters in movies hadn't yet reached its current point of omnipresence, and in a way, this film helped speed that trend along. Compared to Babe, where the most famous voice belonged to Russi Taylor - Who? you ask, and Exactly! I reply. She was Minnie Mouse - Dr. Dolittle has a simply ludicrous compilation of easily-identified figures: starting with MacDonald and Rock and Shandling, and moving on to Ellen DeGeneres, Gilbert Gottfried, Julie Kavner, John Lequizamo, Jenna Elfman (it was 1998, remember), and I don't really know how Brooks got involved, but there you go. The human cast, meanwhile, is made up of a bunch of slumming That Guys: Oliver Platt, Richard Schiff, Jeffrey Tambor, and Paul Giamatti, who wisely managed to remain uncredited, all supplement Boyle and Davis in the small army of famous people who somehow managed to get roped into all this ugliness.

That blend of actors - famous people hiding their shame behind animal effects and less-famous but rather talented overall people appearing onscreen to lend the thing some undeserved legitimacy - would become gruesomely familiar over the next several years, remaining the Way Things Are as recently as 2010's Marmaduke and 2011's The Smurfs. It never works, and the only thing that keeps Dr. Dolittle even a little bit tolerable is the superlative work by the Henson people. Nothing else is remotely fun or appealing or anything but punishing and draggy: director Betty Thomas and cinematographer Russell Boyd (a frequent Peter Weir collaborator) don't ever stop it from looking like it was made for TV, and the jokes are so resolutely unimaginative, consisting of Brooks moping, Rock making gags that are mired in TV-watching, and Murphy playing straight man to all of it, and the script so criminally disinterested even in itself, that the whole thing feels vaguely like it was conceived as a means of punishing the viewer for having any imagination at all (another thing it has in common with so many films to follow). There are plenty of things to nitpick - writers Nat Mauldin and Larry Levin never decide whether or not the animals can actually understand human speech, for starters - but to engage with the film on that level feels like I'd be letting it win by giving it some measure of legitimacy, and I don't want to to that - not when a hundred films made in exactly the same way to exactly the same degraded effect have already won it so many victories, time and again.

Doctor Dolittle, 1967 edition, and Dr. Dolittle, 1998 edition, are more noteworthy for their differences than their similarities: the former is a lumbering behemoth of a musical closely based on the children's stories by author Hugh Lofting of an eccentric Victorian animal lover, the latter takes little from Lofting other than the name, taking place instead in contemporaneous San Francisco. The original is a genteel fable, the remake a broad comedy. Both films are extremely bad, but only the first one was able to snag a nomination for the Best Picture Oscar (and eight others besides; it won two), thereby becoming the easy answer to the question, "What is the worst movie ever nominated for a Best Picture Oscar?"

What divides the movies most of all, however, is the approach they take the central concept, talking to the animals. In 1967, a dapper and visibly unhappy Rex Harrison simply chatted at real-live critters, and informed the humans around him as to what they were saying. The grand advances in technology meant that 31 years later, Eddie Murphy, who very well might have been unhappy, but by that point in his career had probably gotten to used to it, and undoubtedly cried himself to sleep on piles of $100 bills, not only spoke to an assortment of dogs, cats, birds, and so on and so forth; they talked right back to him, in the voices of celebrities who may or may not have taken the job to make something their kids could watch, and more likely did it because they could make a couple hundred grand just by sitting on the phone for 30 minutes. This was before everything in the world was CGI, so the bulk of the animals, though not all of them, were achieved practically, by the technical geniuses at the Jim Henson Creature Shop, and that at least is a blessing: a decade and change later, and this movie would look like Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore.

To understand why the Doctor Dolittle evolution took place, it is instructive to take a look at the world back in 1998. Two things had happened shortly prior to the remake's release that made it, or at least something exactly like it under a different title, all but inevitable. The first was that in the summer of 1995, two talking pig movies were released: the earlier one, Gordy, did very little but to prime the pump for the subsequent Babe, one of the great children's films ever made, for so many reasons, but surely not the least of them is the tremendous quality of the talking animal effects by... the Jim Henson Creature Shop. Babe was a hit, an Academy Award nominee, and a critical darling, and while the unspeakable glut of movies with sassy talking animals wouldn't really ignite until computers put such beasts in the hands of even the shallowest filmmakers, it was in 1995 that the genre began its upwards ascent.

The second thing happened a year later, when a comic star whose career to that point consisted almost entirely of R-rated movies took a gamble on, well, not exactly a family film: it was PG-13 and pretty damn filthy in points. But still, when Eddie Murphy starred in ><>The Nutty Professor, the result was his highest-grossing vehicle since the epochal Beverly Hills Cop II nine years prior, and a film that turned the raunchy funnyman, overnight, into the warm and fuzzy star of any goddamn kiddie picture he could get his hands on, a man who seemingly overnight decided that the only thing he wanted was to cash huge paychecks from starring in gigantic, empty-headed comedies propped up by visual effects and high-concept flim-flam. And before you can say, "you got your anodine juvenile comedy peanut butter in my pop-culture besotted animal-driven kiddie flick", Dr. Dolittle was born, the bastard son of a thousand maniacs.

Insofar as the film's plot was ever novel, that novelty has been seriously compromised by the fact that it's basically the exact same story of every subsequent Murphy vehicle: John Dolittle was once a wide-eyed child who didn't think it was a big deal that he could talk to animals until his dad (Ossie Davis) shamed him into hiding his gift; a great many years later, Dolittle has become a soulless, hateful, wisecracking robot of capitalism, treating his wife (Kristen Wilson) and daughters (Raven-Symoné and Kyla Pratt) with icy indifference, and preparing to send his darling little community health center right up Shit Creek by selling it to a merciless industrial health care CEO (Peter Boyle), and in all possible ways being exactly ready for a life-changing event that will ready him up to be a decent human being and family man. The life-changing event in question is a car accident that leaves him with a bump on the head that re-awakens his dormant gift, when the snotty dog he just hits calls him a bonehead in the dulcet tones of Norm MacDonald.

A great deal of talking-animal buffonery ensues: Dolittle takes his family to a woodland cabin, and word gets out to all the forest creatures that a man who understands their speech and has medical training is nearby; in hardly any time, the doctor has been overwhelmed by sick and hypochondriac animals. Back in San Francisco, he endures the constant barbs of the dog, Lucky, and his younger daughter's guinea pig, Rodney (Chris Rock), while also falling in with a suicidal tiger named Jacob (Albert Brooks). It's good for the film that it's target audience is six-year-olds, since they are the only ones who won't be able to guess where all of this is going (Dolittle acts crazy and it endangers the deal, then he pulls his shit together and saves the day, and tells the big corporate dude that he doesn't want to sell after all), though by the same token, I am unsure that I'd want to let a six-year-old be confronted with some of the jokes, primarily those involving an impotent pigeon (Garry Shandling), or the bit where the tiger is referred to as a pussy. But heck, them's the breaks with joyless pop-culture addicted kids' films, and at least the film was made early enough that it managed largely escape the black hole of shit jokes that most children's entertainment has since become.

Back in 1998, the spectacle of famous actors playing characters in movies hadn't yet reached its current point of omnipresence, and in a way, this film helped speed that trend along. Compared to Babe, where the most famous voice belonged to Russi Taylor - Who? you ask, and Exactly! I reply. She was Minnie Mouse - Dr. Dolittle has a simply ludicrous compilation of easily-identified figures: starting with MacDonald and Rock and Shandling, and moving on to Ellen DeGeneres, Gilbert Gottfried, Julie Kavner, John Lequizamo, Jenna Elfman (it was 1998, remember), and I don't really know how Brooks got involved, but there you go. The human cast, meanwhile, is made up of a bunch of slumming That Guys: Oliver Platt, Richard Schiff, Jeffrey Tambor, and Paul Giamatti, who wisely managed to remain uncredited, all supplement Boyle and Davis in the small army of famous people who somehow managed to get roped into all this ugliness.

That blend of actors - famous people hiding their shame behind animal effects and less-famous but rather talented overall people appearing onscreen to lend the thing some undeserved legitimacy - would become gruesomely familiar over the next several years, remaining the Way Things Are as recently as 2010's Marmaduke and 2011's The Smurfs. It never works, and the only thing that keeps Dr. Dolittle even a little bit tolerable is the superlative work by the Henson people. Nothing else is remotely fun or appealing or anything but punishing and draggy: director Betty Thomas and cinematographer Russell Boyd (a frequent Peter Weir collaborator) don't ever stop it from looking like it was made for TV, and the jokes are so resolutely unimaginative, consisting of Brooks moping, Rock making gags that are mired in TV-watching, and Murphy playing straight man to all of it, and the script so criminally disinterested even in itself, that the whole thing feels vaguely like it was conceived as a means of punishing the viewer for having any imagination at all (another thing it has in common with so many films to follow). There are plenty of things to nitpick - writers Nat Mauldin and Larry Levin never decide whether or not the animals can actually understand human speech, for starters - but to engage with the film on that level feels like I'd be letting it win by giving it some measure of legitimacy, and I don't want to to that - not when a hundred films made in exactly the same way to exactly the same degraded effect have already won it so many victories, time and again.