Blockbuster History: British children's literature

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Warner's humongous summer tentpole Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 and Disney's barely-released Winnie the Pooh represent two very different ways of catering to a family audience, the one a splashy effects-driven adventure, the other so gentle it nearly floats away. They are not, however, the only two ways of adapting a classic work of kiddie lit to the screen, as proven by a recent film that attempted to strike a middle way between effects-driven excess and fealty to its source material .

For a work so central to 20th Century English-language literature that the very title has become a shorthand for a personality type, J.M. Barrie's 1904 play Peter Pan, and his subsequent novelisation Peter and Wendy has proven surprisingly resistant to filmed adaptations. This is partially for the thoroughly pragmatic reason that Barrie turned over the rights for the piece to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, and that institution has done a phenomenal job of keeping a watchful eye over their property. Yet it seems like there should have been more of a cinematic presence for the story than a 1924 feature supervised by Barrie himself, the iconic 1953 Disney animated film, and a smattering of TV movies made in a few different countries (one could also theoretically count the 1991 Steven Spielberg film Hook, but that's at least a touch ridiculous). To put it another way: there were more adaptations of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by the end of the 1920s, counting all the shorts and the like to have stolen ideas from the book, than there have been adaptations of Peter Pan to the time of this writing.

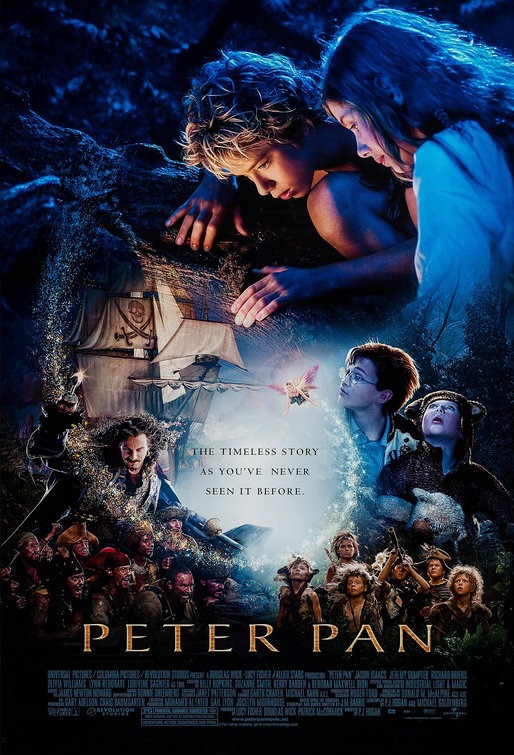

In fact, there was not a single theatrical live-action, sound version of the play released until 2003, and it is with this version of Peter Pan that we shall now concern ourselves. Considering how, until this point, there had been barely any filmed version of the story to speak of, certainly none that could plausibly be called "definitive" - this was the very official version wherein Peter Pan himself was played by an actual boy, and not a tiny woman, for example - it would perhaps have been enough for director P.J. Hogan, who co-wrote the script with Michael Goldenberg, to have simply attempted a completely literal treatment of the story; instead, in keeping with the spirit of the times, Hogan's version is what we might call the "darker, edgier Peter Pan", though darker & edgier means something different in the context of a PG-rated family film than it does in the case of e.g. a superhero reboot. Functionally, the act of bringing Peter Pan up to date for a modern audience meant one thing above all else: fill it the hell up with sex.

Not actual sex. That would have been illegal: Jeremy Sumpter, who plays Peter, was 14 when the movie came out; Rachel Hurd-Wood, playing Wendy, was 13. But the chief change Hogan made to the text, which wasn't really even a change at all, so much as a foregrounding of themes already present in the material, was to strongly emphasise the degree to which Peter Pan is a parable about the onset of puberty, that lovely period of grotesque mental trauma, of fascination with and terror of one's suddenly very inescapable sexual urges. "I don't want to grow up", the clarion call of Peter Pan for over a century, has usually been depicted as a fear of responsibility and the boredom that comes along with it; but there's really no way to deny that reading the whole thing as a metaphor for the way that little boys start to be really darn confused by little girls, and the way that little girls start to be really darn irritated by how much little boys act like morons. It's just that historically, adults don't like very much to think of 12-year-olds as budding little sexual beings - certainly Barrie, stalwart Edwardian gentleman that he was, wouldn't have been able to wrap his mind around the idea - so that idea that Wendy gives Peter some very funny feelings, and vice versa, has been largely ignored in the popular treatments of the story (I will not pretend to have much or any knowledge in the field of Peter Pan scholarship), outside of the celebrated bit about the kiss that turns out to be a thimble when Wendy loses her nerve.

So kudos, I guess, to Hogan for really digging in deep to this rich vein of subtext, and playing it out every which way he could: by inventing a few new plot points that allow Wendy to play Peter off of his nemesis Captain Hook (Jason Isaacs) as not just an existential threat, but as a grown-up competitor for her attention and affections (and since, following tradition, Isaacs also plays Wendy's father George Darling, the idea that she's using him as a means of ginning up sexual jealousy with Peter finds a kind of ickiness that I'm happier not thinking about); the customary plot thread in which Peter's diminutive fairy friend Tinker Bell views Wendy through a lens of specifically sexual jealous is ramped up considerably, not least by the mere casting of the inordinately sexy Ludivine Sagnier.

But all that being said, it's not like this is some pornographically excessive version of Peter Pan that's all about hormone-addled teen rutting. That's just the way that Hogan stamps it as a product of its specific era. In the main, the film is exactly what it presents itself as being: an attempt to capture all the whimsy and fantasy of the play in cinema, using all the best technical toys available to a filmmaker given an excessive amount of money in 2002. The result is a somewhat unsteady mixture of Barrie's sweet-unto-cloying language and fantastic conceits with a distinctly more modern wackiness, but on the whole it's a pleasant thing, if hardly the definitive treatment of the source material - which, at any rate, it doesn't really pretend to be.

Peter Pan being more of a concept than a narrative, and a well-known concept at that, I'll just run through the plot synopsis quickly: in London, in the first decade of the 20th Century, the three Darling children, Wendy, John (Harry Newell), and Michael (Freddie Popplewell) are thrown into crisis when their parents, George and Mary (Olivia Williams), begin to wonder if Wendy is becoming too much of a young lady to keep living the frivolous life of a girl with a Newfoundland dog as a nanny. This is equally distressing for the magical boy Peter Pan, who eavesdrops on Wendy's stories every night, and so he flies the three siblings away to Neverland, his magical world of boys' own adventures, where there are jungles and mermaids and Indians and pirates, led by the cruel Captain Hook. All sorts of dazzling adventures ensue, ending with Peter and Hook in a showdown over the fate of Wendy, her brothers, and the Lost Boys, young English lads that Peter has stolen away over the years, that they might not have to grow up. It's not exactly the same as the original (there is a new character, Aunt Millicent, who has no obvious function but to provide a role for beloved actress Lynn Redgrave), but the heart is there.

To create this magical world, the effects experts at ILM spend a huge pile of money (the official $100 million budget figure is widely held to be under-reported) building a version of Neverland that is blatantly artificial and absolutely perfect in its whimsy; production designer Robert Ford contributes more to the final effect of the movie than P.J. Hogan does, so absolutely present are his delightfully crazy ideas (the depiction of outer space, between London and Neverland, is my favorite part, with planets and nebulae all crammed together like big plaster balls in a playground), and so lovingly does Hogan foreground them. Indeed, my first impression of the movie was that it was essentially Moulin Rouge! for children - and that was before I found out that they shared a cinematographer, Donald M. McAlpine - given how absolutely unreal everything looked, and given the disorientingly energetic treatment the director gives to everything, visually.

If there is one major flaw in this Peter Pan, in fact, it's that Hogan's direction is a bit too urgently Big and Zany and Wild, particularly in the early going (actually, I expect it's more that one gets used to it as it goes on, though zaniness is better-suited to Neverland than to the streets of London, for a certainty), without the sense one gets with Baz Luhrmann that he's doing it all for some coherent purpose. He delights in using direct address shots, actors staring right into the camera, often as it rushes into their face, and it doesn't take a lot for this to become wearying: used sparingly, this can be one of the most bracing images in cinema, but when it gets splattered all over every moment of a movie, it becomes quickly apparent why it rarely is done. And more times than I can immediately recall, the production design is the focal point of an image at the expense of the characters, as if the director simply wanted to gawk.

In fact, I can easily imagine this Peter Pan being a bit of a grind, but for one thing: the cast is phenomenal in every respect, particularly the key roles of Peter and Hook. Sumpter is unaccountably brilliant, and it seems criminal that he hasn't been in anything of particular note since then; a stint on Friday Night Lights is pretty much it as far as prestigious projects goes. Not a fair fate at all for a young man who so perfectly evokes the dichotomy of Peter's two dominant modes: a petulant, cocksure asshole who cares not a whit about anyone else around him, and a sensitive child crippled by fear of things he can't control and terrified that somebody will find out. As for Isaacs, his portrayal of Hook as a weary middle-aged man, not a raving monster, is right in keeping with the film's thematic concerns, and though I think he does too much to differentiate the pirate from Mr. Darling, thereby muddying the whole point of having one actor play both parts, it's a great piece of subdued character acting from a man who has too readily fallen into the trap of being "that guy who doesn't make much of an impression in the Harry Potter films".

I won't lie: I could do with a little more human feeling and a little less spectacle in my Peter Pan. But at least this one doesn't have a gigantic racist musical number about Native Americans. And the actors are always there to keep things grounded whenever Hogan gets too excited about his effects and sets. It's not the best version of this story imaginable, but it's certainly the right film for the time it was made: combining sentiment and garish overstatement in a blend that works in spite of itself, a proper early-'00s popcorn movie; that it manages to do right by Barrie and even freshen up the edges of his achingly familiar work is the difference between this being a decent enough movie and a genuinely good one, a minor success, but one that deserves much more respect and attention than it has managed to scrounge up in the years since its release.

For a work so central to 20th Century English-language literature that the very title has become a shorthand for a personality type, J.M. Barrie's 1904 play Peter Pan, and his subsequent novelisation Peter and Wendy has proven surprisingly resistant to filmed adaptations. This is partially for the thoroughly pragmatic reason that Barrie turned over the rights for the piece to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, and that institution has done a phenomenal job of keeping a watchful eye over their property. Yet it seems like there should have been more of a cinematic presence for the story than a 1924 feature supervised by Barrie himself, the iconic 1953 Disney animated film, and a smattering of TV movies made in a few different countries (one could also theoretically count the 1991 Steven Spielberg film Hook, but that's at least a touch ridiculous). To put it another way: there were more adaptations of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by the end of the 1920s, counting all the shorts and the like to have stolen ideas from the book, than there have been adaptations of Peter Pan to the time of this writing.

In fact, there was not a single theatrical live-action, sound version of the play released until 2003, and it is with this version of Peter Pan that we shall now concern ourselves. Considering how, until this point, there had been barely any filmed version of the story to speak of, certainly none that could plausibly be called "definitive" - this was the very official version wherein Peter Pan himself was played by an actual boy, and not a tiny woman, for example - it would perhaps have been enough for director P.J. Hogan, who co-wrote the script with Michael Goldenberg, to have simply attempted a completely literal treatment of the story; instead, in keeping with the spirit of the times, Hogan's version is what we might call the "darker, edgier Peter Pan", though darker & edgier means something different in the context of a PG-rated family film than it does in the case of e.g. a superhero reboot. Functionally, the act of bringing Peter Pan up to date for a modern audience meant one thing above all else: fill it the hell up with sex.

Not actual sex. That would have been illegal: Jeremy Sumpter, who plays Peter, was 14 when the movie came out; Rachel Hurd-Wood, playing Wendy, was 13. But the chief change Hogan made to the text, which wasn't really even a change at all, so much as a foregrounding of themes already present in the material, was to strongly emphasise the degree to which Peter Pan is a parable about the onset of puberty, that lovely period of grotesque mental trauma, of fascination with and terror of one's suddenly very inescapable sexual urges. "I don't want to grow up", the clarion call of Peter Pan for over a century, has usually been depicted as a fear of responsibility and the boredom that comes along with it; but there's really no way to deny that reading the whole thing as a metaphor for the way that little boys start to be really darn confused by little girls, and the way that little girls start to be really darn irritated by how much little boys act like morons. It's just that historically, adults don't like very much to think of 12-year-olds as budding little sexual beings - certainly Barrie, stalwart Edwardian gentleman that he was, wouldn't have been able to wrap his mind around the idea - so that idea that Wendy gives Peter some very funny feelings, and vice versa, has been largely ignored in the popular treatments of the story (I will not pretend to have much or any knowledge in the field of Peter Pan scholarship), outside of the celebrated bit about the kiss that turns out to be a thimble when Wendy loses her nerve.

So kudos, I guess, to Hogan for really digging in deep to this rich vein of subtext, and playing it out every which way he could: by inventing a few new plot points that allow Wendy to play Peter off of his nemesis Captain Hook (Jason Isaacs) as not just an existential threat, but as a grown-up competitor for her attention and affections (and since, following tradition, Isaacs also plays Wendy's father George Darling, the idea that she's using him as a means of ginning up sexual jealousy with Peter finds a kind of ickiness that I'm happier not thinking about); the customary plot thread in which Peter's diminutive fairy friend Tinker Bell views Wendy through a lens of specifically sexual jealous is ramped up considerably, not least by the mere casting of the inordinately sexy Ludivine Sagnier.

But all that being said, it's not like this is some pornographically excessive version of Peter Pan that's all about hormone-addled teen rutting. That's just the way that Hogan stamps it as a product of its specific era. In the main, the film is exactly what it presents itself as being: an attempt to capture all the whimsy and fantasy of the play in cinema, using all the best technical toys available to a filmmaker given an excessive amount of money in 2002. The result is a somewhat unsteady mixture of Barrie's sweet-unto-cloying language and fantastic conceits with a distinctly more modern wackiness, but on the whole it's a pleasant thing, if hardly the definitive treatment of the source material - which, at any rate, it doesn't really pretend to be.

Peter Pan being more of a concept than a narrative, and a well-known concept at that, I'll just run through the plot synopsis quickly: in London, in the first decade of the 20th Century, the three Darling children, Wendy, John (Harry Newell), and Michael (Freddie Popplewell) are thrown into crisis when their parents, George and Mary (Olivia Williams), begin to wonder if Wendy is becoming too much of a young lady to keep living the frivolous life of a girl with a Newfoundland dog as a nanny. This is equally distressing for the magical boy Peter Pan, who eavesdrops on Wendy's stories every night, and so he flies the three siblings away to Neverland, his magical world of boys' own adventures, where there are jungles and mermaids and Indians and pirates, led by the cruel Captain Hook. All sorts of dazzling adventures ensue, ending with Peter and Hook in a showdown over the fate of Wendy, her brothers, and the Lost Boys, young English lads that Peter has stolen away over the years, that they might not have to grow up. It's not exactly the same as the original (there is a new character, Aunt Millicent, who has no obvious function but to provide a role for beloved actress Lynn Redgrave), but the heart is there.

To create this magical world, the effects experts at ILM spend a huge pile of money (the official $100 million budget figure is widely held to be under-reported) building a version of Neverland that is blatantly artificial and absolutely perfect in its whimsy; production designer Robert Ford contributes more to the final effect of the movie than P.J. Hogan does, so absolutely present are his delightfully crazy ideas (the depiction of outer space, between London and Neverland, is my favorite part, with planets and nebulae all crammed together like big plaster balls in a playground), and so lovingly does Hogan foreground them. Indeed, my first impression of the movie was that it was essentially Moulin Rouge! for children - and that was before I found out that they shared a cinematographer, Donald M. McAlpine - given how absolutely unreal everything looked, and given the disorientingly energetic treatment the director gives to everything, visually.

If there is one major flaw in this Peter Pan, in fact, it's that Hogan's direction is a bit too urgently Big and Zany and Wild, particularly in the early going (actually, I expect it's more that one gets used to it as it goes on, though zaniness is better-suited to Neverland than to the streets of London, for a certainty), without the sense one gets with Baz Luhrmann that he's doing it all for some coherent purpose. He delights in using direct address shots, actors staring right into the camera, often as it rushes into their face, and it doesn't take a lot for this to become wearying: used sparingly, this can be one of the most bracing images in cinema, but when it gets splattered all over every moment of a movie, it becomes quickly apparent why it rarely is done. And more times than I can immediately recall, the production design is the focal point of an image at the expense of the characters, as if the director simply wanted to gawk.

In fact, I can easily imagine this Peter Pan being a bit of a grind, but for one thing: the cast is phenomenal in every respect, particularly the key roles of Peter and Hook. Sumpter is unaccountably brilliant, and it seems criminal that he hasn't been in anything of particular note since then; a stint on Friday Night Lights is pretty much it as far as prestigious projects goes. Not a fair fate at all for a young man who so perfectly evokes the dichotomy of Peter's two dominant modes: a petulant, cocksure asshole who cares not a whit about anyone else around him, and a sensitive child crippled by fear of things he can't control and terrified that somebody will find out. As for Isaacs, his portrayal of Hook as a weary middle-aged man, not a raving monster, is right in keeping with the film's thematic concerns, and though I think he does too much to differentiate the pirate from Mr. Darling, thereby muddying the whole point of having one actor play both parts, it's a great piece of subdued character acting from a man who has too readily fallen into the trap of being "that guy who doesn't make much of an impression in the Harry Potter films".

I won't lie: I could do with a little more human feeling and a little less spectacle in my Peter Pan. But at least this one doesn't have a gigantic racist musical number about Native Americans. And the actors are always there to keep things grounded whenever Hogan gets too excited about his effects and sets. It's not the best version of this story imaginable, but it's certainly the right film for the time it was made: combining sentiment and garish overstatement in a blend that works in spite of itself, a proper early-'00s popcorn movie; that it manages to do right by Barrie and even freshen up the edges of his achingly familiar work is the difference between this being a decent enough movie and a genuinely good one, a minor success, but one that deserves much more respect and attention than it has managed to scrounge up in the years since its release.