Leave it to Beaver

It's not the fault of anybody involved with the production of the long-completed, just-released The Beaver that it has been forced into the difficult position of being the first stop on the Mel Gibson Comeback Whistle-Stop Tour (okay, so I suppose it's Mel Gibson's fault, but you know what I mean). Nor is it anything other than one of those coincidences that will sometimes happen that The Beaver's themes and even some of its particulars are uncomfortably similar to the controversies surrounding the racist, misogynist, physically abusive actor. The Beaver asked for none of this; and The Beaver is not up to the strain of all this. It is a slender reed of an indie drama about depression and a family collapsing from within, made with greater intentions than skill by director and co-star Jodie Foster, working behind the camera for the first time in a decade and a half, who is one of those actors-turned-directors that people always describe with a bit too much enthusiasm as being "great with actors!" because that is pretty much the only nice thing there is to say about the directing and one likes Foster as a human being too much to want to stress the fact that she is kind of bad at the rest of her job.

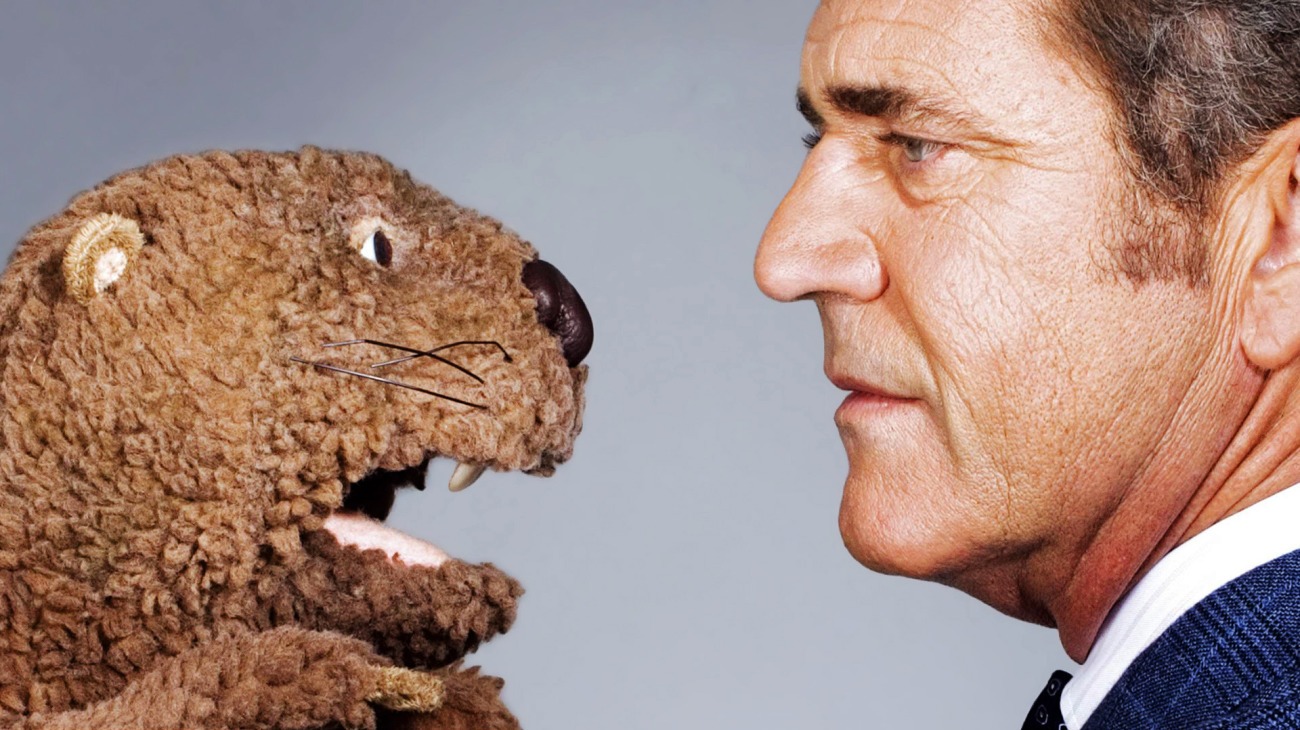

In the film, Gibson plays Walter Black, a man with a ridiculously on-the-nose surname. Walter suffers from crippling depression, the kind that makes it hard to do anything beyond the most basic functions of organic life, and even that only because other people make him do it. There comes a time when his terrified and exasperated wife, Meredith (Foster) simply can't take it any more, and throws him out. Looking to find a place to throw out his worldly belongings, Walter spots a plush beaver hand puppet in a dumpster, and impulsively grabs it before checking into a hotel room to commit suicide. When that doesn't turn out exactly right, Walter wakes up to find the beaver has a life of its own; that is to say, Walter has taken to talking through the puppet using a magnificently fake Cockney accent, and investing what remains of his shattered personality into the toy. In essence, the beaver is the functional, happy, living Walter, and the actual Walter is only the empty fleshy shell that used to contain a happy family man and toy company executive. Meredith is confused but hopeful by this development, their younger son Henry (Riley Thomas Stewart) is delighted by the wacky friend he now has in his father, and teenage son Porter (Anton Yelchin) doesn't even try to hide his contempt for the whole situation. The movie proceeds to watch this play out, with special emphasis on the parallel stories of Walter and the beaver, and Porter (who is terrified that he's turning into his father) and his job ghostwriting papers for other students, which comes to a head when the pretty valedictorian Norah (Jennifer Lawrence) asks him to write her graduation speech.

The Beaver is built on metaphors; the Walter/Porter storylines are both about lost men using other identities for their "voice". The Beaver is also the kind of movie where it's easy to point out what the metaphors are, and not complete easy to say what the metaphors mean, and this is because deep down, the film has no idea what it's saying about anything. By all means, I am grateful to first-timer Kyle Killen for writing a screenplay about depression that is, by and large, a fair depiction of what depression is or at least can be, and not the airy Hollywood version of mental illness that suggests it can be cured if Natalie Portman scrunches up her nose enough at the male protagonist. That said, it's never really clear if The Beaver is "about" depression, or if depression is being used as a metaphor (that word again!) for a grander cultural anomie. There's not a single idea that the script presents that gets full explored, though if this is Killen's fault or Foster's, it's hard to tell.

Certainly, it's hard to think of much nice to say about the watery execution of the script by its director, whose ideas about how to visualise the themes and character beats of the story could hardly be more obvious, or leading. Lots of overcast days, artfully distressed interiors, meaningful close-ups of the physical manifestations of Walter and Porter's emotional pain. At the same time, the framing is wall-to-wall plain close-ups and two-shots, which combined with the omnipresent sense of gloom, suggests a Bergman film made by a veteran of TV sitcoms. A film about the destructive anguish of depression isn't meant to be joyful, of course, but The Beaver is too banal to be probing. Not to mention, the director has either ignored or missed some fairly obvious cues that the screenplay she's working with was designed as a pitch black comedy: certainly, the climactic dart into unabashed kitschiness doesn't fit with the hushed, clammy tone Foster works so hard to maintain elsewhere, and she seems curiously uninterested in playing, at all, with the inherent absurdity of a man using a beaver puppet to talk like a gangster in a Guy Ritchie film (though I'll confess that, by doing nothing to differentiate the film's aesthetic, Foster shoots the beaver just like any other character, which has a weirdly electrifying effect). Foster's last film, Home for the Holidays, wasn't nearly this leaden; perhaps The Beaver was a hard set, or perhaps the director can't handle the extra pressure of being onscreen in her own movie.

But she's great with actors! Though not with herself: indeed, her performance matches her direction, rendering Meredith inert - a criminal misstep for such a challenging character who needs to be played with greater sensitivity than Foster is here able to bring to the role. For in Meredith, we find someone who has put up with a lot of shit, and can't be blamed for running out of patience; and yet at every turn, she does exactly the wrong thing. It's a tricky blend of sympathy and culpability that the film desperately wants, and gets not at all. We have to wait too long between Jodie Foster vehicles for this kind of slackness to be even a little bit okay.

On the other hand, Gibson, Yelchin, and Lawrence (who had not yet enjoyed her big debutante party with Winter's Bone when this project was filmed) are all terrifically good: Lawrence gets the least to do, but manages to invest her undernourished character with enough unspoken history to make the script's functional treatment of her work, while Yelchin does a fantastic job navigating a character who is so mired in fear that he could be said to have no inner self, only the negative antithesis of a self. It's Gibson who the film most needs to nail a difficult part, though, and the actor rises to the occasion with a brilliant performance, easily the best thing he's done since well back into the 1980s. He's a shitty person, that's beyond question; but shitty people can be fantastic actors, too, and his balance of two characters - both of whom he has to play onscreen simultaneously - is absolutely impressive, as is the much less showy work of playing depression as the condition of feeling empty: however one plays the lack of affect and manages to make it engaging and fascinating, Gibson does that here, drawing on those well-publicised demons of his to create a character that is a believably tormented as any depressed protagonist has been in many years.

Gibson's work as Walter is by far the best thing The Beaver has going for it, and he manages to sell the otherwise underdeveloped themes of mental pain enough that the film ends up coming much closer to working than it has any proper reason to. Which is to say, it still doesn't work, and no amount of wishing that Foster and Killen had put even a tiny bit more thought into what they were doing can make this a completely satisfying study of depression or an appealingly savage dark comedy. There's an uncommitted, utterly impersonal air covering the whole thing, and just because the main character might be that disaffected, there's no reason the movie about him needs to follow suit.

6/10