Blockbuster History: Comedy sequels

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the single best piece of counter-programming of the year has to be the head-to-head faceoff between two intensely different comedy sequels, R-rated frat epic The Hangover, Part II and family-friendly animal adventure Kung Fu Panda 2. The comedy sequel is a rough problem for many filmmakers: the films that don't simply repeat the original note for note often suffer from mere exhaustion. Today's example of the form is no exception.

Even today, when sequels are planned before the original film has finished shooting, and it's assumed as a matter of course that the bulk of the audience will have a fairly intimate knowledge of all the esoterica of series mythology, one must stand in a little bit of awe of the makers of Ghostbusters II, and their massive, granite cojones. Here is how the movie begins: the Columbia logo, with no audio playing underneath, and then to a title card, accompanied by a chord: "FIVE YEARS LATER". There is no pussyfooting around, now acting like this is just a movie for anybody to come and enjoy. No sir, the people behind Ghostbusters II know damn good and well that you came to see the follow-up to Ghostbusters, and that you have not stumbled into the theater by accident. The filmmakers in fact are more than a little bit smug about how much they know you loved Ghostbusters, that they can open the film with just the words "FIVE YEARS LATER". Five years later than what? is not even a possible question. Five years later than when we fucking blew your mind, is what.

They don't even include the title, in fact - there is never onscreen text reading Ghostbusters II, anywhere in the movie.* After the opening scene, there is simply an animation of the ghost from the first movie's logo, thrusting his hand towards us, two fingers thrust in the air. "We don't even need to motherfucking tell you what movie you're watching," say the filmmakers, "you know you're here to see the follow-up to Ghostbusters. Which was iconic and beloved, and that's why the title is just the classic image that, in all probability, you have on a T-shirt". There is a faintly unlovable feeling of entitlement to all this, in fact, which is not at all a rare sensation one gets while watching a sequel, but it's especially baldly expressed in this case.

I have no Aesop-style moral to this story: as the sequel to the second-highest grossing film of 1984 (Ghostbusters broke $200 million back when breaking $200 million really meant something), Ghostbusters II was met with a level of enthusiasm that justified all of the filmmakers' presumption; it set the record for highest three-day weekend box office of all time upon its release, a distinction it held for one week (and the previous record had been set all of three weeks earlier; 1989 was a really special summer).† Clearly, all that pent-up desire was very real.

That's why it's a bit of wrench that Ghostbusters II is kind of just a little bit lousy. Not an atrocity in the eyes of a loving God, or anything like that. It is, however, an almost uniformly substandard follow-up that, since the original film remains so beloved by so many people, still gets to be disappointing even two decades and change later. What's really special about Ghostbusters II is that it manages to hit all three of the great sins of movie sequels all at once; which actually takes quite a bit of doing. In fact, I cannot immediately think of another example of a film that does so besides Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me and The Jewel of the Nile, though I am eager to have readers remind me of the ones I missed.

The first of these sins is of deciding that since the original was good, audiences really just want the original again, exactly the same way, but with some different sets and costumes; in the particular case of comedies, this often translates into "the same jokes, but broader", much as it translates, for action movies, into "the same explosions, but bigger". The most egregious example in Ghostbusters II involves the climax; since the original had a large creature stomping down the streets of New York, so must this sequel, even though it requires a nearly heroic level of contrivance and sheer bullshit to set up even the rickety justification that we get here.

The second, very closely related, is that in order to re-create the situations that made the original beloved, a giant reset button has to be pushed (we might well call this the Jewel of the Nile Rule, so appallingly does that film set things back to square 1). The snarky interplay between Bill Murray and Sigourney Weaver was great the last time? Let's whip up some clumsy explanation of how they broke up in between movies, so we can see her reject his advances again (never mind that it would be infinitely more rewarding to see how their interplay has changed as a result of time spent together). Even worse, since the original movie had a long sequence in which the Ghostbusters were fighting the prejudices of a skeptical world, Ghostbusters II absolutely must spend its first act showcasing how the heroes tumbled into obsolescence and shame, despite the fact that this would seem to be completely impossible given the climax of the first movie. It's especially galling, given that there is virtually nothing inherent in the plot that requires the Ghostbusters have to start from scratch; several scenes would require the change of only a line or two to accommodate a new scenario, in which the Ghostbusters remain in-demand and the toast of the city, and still get thrust into this strange new event.

It's the third sin, though, that really breaks a movie. The first two are essentially fanboyish nitpicking, but the third is unanswerable. This is when a sequel is made because there is a market demand, not because the makers have some creative idea about what can be done to extend the world built up in the first film. Its symptoms are a certain detached, mechanical approach to the art of filmmaking, the almost palpable sense that the people making the movie just do not want to be there. Despite sharing with its predecessor director Ivan Reitman, writers Harold Ramis and Dan Aykroyd, Ghostbusters II has none of the same inspiration; the plot is somehow both more convoluted and more rote at the same time, involving all sorts of weird, hastily-expressed conceits, all in service to a brutally routine "the big bad wants to kill everybody" scenario.

Look no further than Bill Murray, the animating spirit of Ghostbusters, with his bone-dry sardonic quips and aura of just goofing around because he could; by his own admission, he didn't have much love for this project, and his snark and - critically - his ad-libbing are much toned-down from the last film. You can just tell he's not having as much fun, and when Bill Murray isn't having fun, nobody is having fun.

There are other issues; the addition of a baby is the kind of criminally bad idea much beloved of third-rate sitcoms, and Ramis & Aykroyd should certainly have known better, while the saccharine sentimentality (the movie's conflict is expressly in terms of "being an urban jerk makes things bad, but singing and being happy makes things good") serves only to further bury the Murrayesque snark that made the original such a pip.

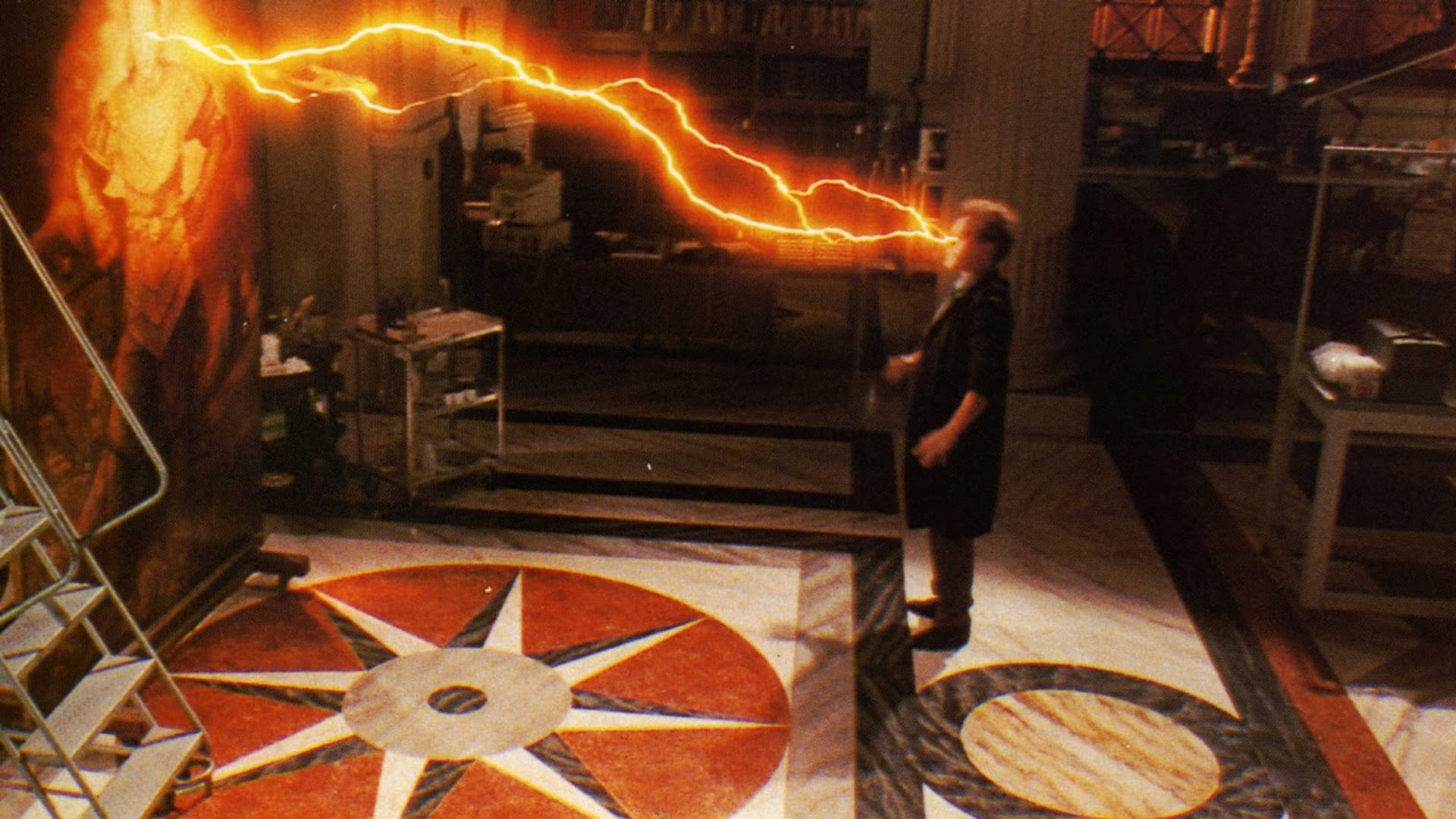

All that said - and make no mistake, I do not like this movie - Ghostbusters II manages to do some things right. The core of Murray, Aykroyd, Ramis, and Ernie Hudson (who still gets shunted to the side, despite his character being present from the opening this time) remain fun to watch, even with Murray stuck in first gear; the bit of the story about how the ancient evil warlock trying to come back is basically Dracula and the quisling art restorer who does his bidding is basically Renfield, is the kind of lightly-applied detail that is all the more charming for being mostly invisible (also charming: the Renfield-analogue is played by Peter MacNicol, who would go on to play the actual Renfield in Mel Brook's earth-shatteringly misbegotten Dracula: Dead and Loving It). The visual effects were pretty damn top-notch in 1989, and remain absolutely heartwarming to those of us who love a good practical effect. And the whole thing is at times pretty effectively creepy: for some odd reason, Ghostbusters II seems to amp up the scares over the comedy (or maybe the comedy just doesn't work: between Murray's disengagement and the grating exaggeration of Rick Moranis's most unpleasantly bumbling qualities compared to the first film, there does seem to be an awful lot of bad humor going on), but sequences like the hunt through a murky subway are quite agreeably spooky for what amounts to a family comedy from the late '80s.

That is: Ghostbusters II has flashes of inspiration imprisoned in boilerplate, a film marginally better than the average almost solely because of its cast, but without any spark of delight. It's not hugely misconceived or mangled by people with no connection to the series; it's simply not put together as well. And that is somehow the more painful, for one cannot get angry at it, or imagine a better version. It does not squander goodwill, it lets goodwill leak out slowly, and it chiefly for this reason I have absolutely no desire to ever see a Ghostbusters III: imagine how horrible it would be to have this same muddy lack of insight coupled with how much older they all are now, and the impersonal mediocrity of the first sequel would almost by necessity expand to apocalyptic proportions.

Reviews in this series

Ghostbusters (I. Reitman, 1984)

Ghostbusters II (I. Reitman, 1989)

Ghostbusters (Feig, 2016)

Ghostbusters: Afterlife (J. Reitman, 2021)

*Maybe buried somewhere deep in the end credits. I wasn't paying that close attention.

Even today, when sequels are planned before the original film has finished shooting, and it's assumed as a matter of course that the bulk of the audience will have a fairly intimate knowledge of all the esoterica of series mythology, one must stand in a little bit of awe of the makers of Ghostbusters II, and their massive, granite cojones. Here is how the movie begins: the Columbia logo, with no audio playing underneath, and then to a title card, accompanied by a chord: "FIVE YEARS LATER". There is no pussyfooting around, now acting like this is just a movie for anybody to come and enjoy. No sir, the people behind Ghostbusters II know damn good and well that you came to see the follow-up to Ghostbusters, and that you have not stumbled into the theater by accident. The filmmakers in fact are more than a little bit smug about how much they know you loved Ghostbusters, that they can open the film with just the words "FIVE YEARS LATER". Five years later than what? is not even a possible question. Five years later than when we fucking blew your mind, is what.

They don't even include the title, in fact - there is never onscreen text reading Ghostbusters II, anywhere in the movie.* After the opening scene, there is simply an animation of the ghost from the first movie's logo, thrusting his hand towards us, two fingers thrust in the air. "We don't even need to motherfucking tell you what movie you're watching," say the filmmakers, "you know you're here to see the follow-up to Ghostbusters. Which was iconic and beloved, and that's why the title is just the classic image that, in all probability, you have on a T-shirt". There is a faintly unlovable feeling of entitlement to all this, in fact, which is not at all a rare sensation one gets while watching a sequel, but it's especially baldly expressed in this case.

I have no Aesop-style moral to this story: as the sequel to the second-highest grossing film of 1984 (Ghostbusters broke $200 million back when breaking $200 million really meant something), Ghostbusters II was met with a level of enthusiasm that justified all of the filmmakers' presumption; it set the record for highest three-day weekend box office of all time upon its release, a distinction it held for one week (and the previous record had been set all of three weeks earlier; 1989 was a really special summer).† Clearly, all that pent-up desire was very real.

That's why it's a bit of wrench that Ghostbusters II is kind of just a little bit lousy. Not an atrocity in the eyes of a loving God, or anything like that. It is, however, an almost uniformly substandard follow-up that, since the original film remains so beloved by so many people, still gets to be disappointing even two decades and change later. What's really special about Ghostbusters II is that it manages to hit all three of the great sins of movie sequels all at once; which actually takes quite a bit of doing. In fact, I cannot immediately think of another example of a film that does so besides Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me and The Jewel of the Nile, though I am eager to have readers remind me of the ones I missed.

The first of these sins is of deciding that since the original was good, audiences really just want the original again, exactly the same way, but with some different sets and costumes; in the particular case of comedies, this often translates into "the same jokes, but broader", much as it translates, for action movies, into "the same explosions, but bigger". The most egregious example in Ghostbusters II involves the climax; since the original had a large creature stomping down the streets of New York, so must this sequel, even though it requires a nearly heroic level of contrivance and sheer bullshit to set up even the rickety justification that we get here.

The second, very closely related, is that in order to re-create the situations that made the original beloved, a giant reset button has to be pushed (we might well call this the Jewel of the Nile Rule, so appallingly does that film set things back to square 1). The snarky interplay between Bill Murray and Sigourney Weaver was great the last time? Let's whip up some clumsy explanation of how they broke up in between movies, so we can see her reject his advances again (never mind that it would be infinitely more rewarding to see how their interplay has changed as a result of time spent together). Even worse, since the original movie had a long sequence in which the Ghostbusters were fighting the prejudices of a skeptical world, Ghostbusters II absolutely must spend its first act showcasing how the heroes tumbled into obsolescence and shame, despite the fact that this would seem to be completely impossible given the climax of the first movie. It's especially galling, given that there is virtually nothing inherent in the plot that requires the Ghostbusters have to start from scratch; several scenes would require the change of only a line or two to accommodate a new scenario, in which the Ghostbusters remain in-demand and the toast of the city, and still get thrust into this strange new event.

It's the third sin, though, that really breaks a movie. The first two are essentially fanboyish nitpicking, but the third is unanswerable. This is when a sequel is made because there is a market demand, not because the makers have some creative idea about what can be done to extend the world built up in the first film. Its symptoms are a certain detached, mechanical approach to the art of filmmaking, the almost palpable sense that the people making the movie just do not want to be there. Despite sharing with its predecessor director Ivan Reitman, writers Harold Ramis and Dan Aykroyd, Ghostbusters II has none of the same inspiration; the plot is somehow both more convoluted and more rote at the same time, involving all sorts of weird, hastily-expressed conceits, all in service to a brutally routine "the big bad wants to kill everybody" scenario.

Look no further than Bill Murray, the animating spirit of Ghostbusters, with his bone-dry sardonic quips and aura of just goofing around because he could; by his own admission, he didn't have much love for this project, and his snark and - critically - his ad-libbing are much toned-down from the last film. You can just tell he's not having as much fun, and when Bill Murray isn't having fun, nobody is having fun.

There are other issues; the addition of a baby is the kind of criminally bad idea much beloved of third-rate sitcoms, and Ramis & Aykroyd should certainly have known better, while the saccharine sentimentality (the movie's conflict is expressly in terms of "being an urban jerk makes things bad, but singing and being happy makes things good") serves only to further bury the Murrayesque snark that made the original such a pip.

All that said - and make no mistake, I do not like this movie - Ghostbusters II manages to do some things right. The core of Murray, Aykroyd, Ramis, and Ernie Hudson (who still gets shunted to the side, despite his character being present from the opening this time) remain fun to watch, even with Murray stuck in first gear; the bit of the story about how the ancient evil warlock trying to come back is basically Dracula and the quisling art restorer who does his bidding is basically Renfield, is the kind of lightly-applied detail that is all the more charming for being mostly invisible (also charming: the Renfield-analogue is played by Peter MacNicol, who would go on to play the actual Renfield in Mel Brook's earth-shatteringly misbegotten Dracula: Dead and Loving It). The visual effects were pretty damn top-notch in 1989, and remain absolutely heartwarming to those of us who love a good practical effect. And the whole thing is at times pretty effectively creepy: for some odd reason, Ghostbusters II seems to amp up the scares over the comedy (or maybe the comedy just doesn't work: between Murray's disengagement and the grating exaggeration of Rick Moranis's most unpleasantly bumbling qualities compared to the first film, there does seem to be an awful lot of bad humor going on), but sequences like the hunt through a murky subway are quite agreeably spooky for what amounts to a family comedy from the late '80s.

That is: Ghostbusters II has flashes of inspiration imprisoned in boilerplate, a film marginally better than the average almost solely because of its cast, but without any spark of delight. It's not hugely misconceived or mangled by people with no connection to the series; it's simply not put together as well. And that is somehow the more painful, for one cannot get angry at it, or imagine a better version. It does not squander goodwill, it lets goodwill leak out slowly, and it chiefly for this reason I have absolutely no desire to ever see a Ghostbusters III: imagine how horrible it would be to have this same muddy lack of insight coupled with how much older they all are now, and the impersonal mediocrity of the first sequel would almost by necessity expand to apocalyptic proportions.

Reviews in this series

Ghostbusters (I. Reitman, 1984)

Ghostbusters II (I. Reitman, 1989)

Ghostbusters (Feig, 2016)

Ghostbusters: Afterlife (J. Reitman, 2021)

*Maybe buried somewhere deep in the end credits. I wasn't paying that close attention.