Allegory of the cave

There is a cave system in the south of France, named Chauvet after one of the three people who discovered in 1994. The Chauvet cave contains a wealth of paintings created by Stone Age artists; there are the usual dating controversies that crop up whenever people want to find exact dates for things that happened a really damn long time ago, but solid scholarship indicatess that the oldest of these paintings may have been created as long as 32,000 years ago, and would thus be the most ancient cave paintings known to exist.

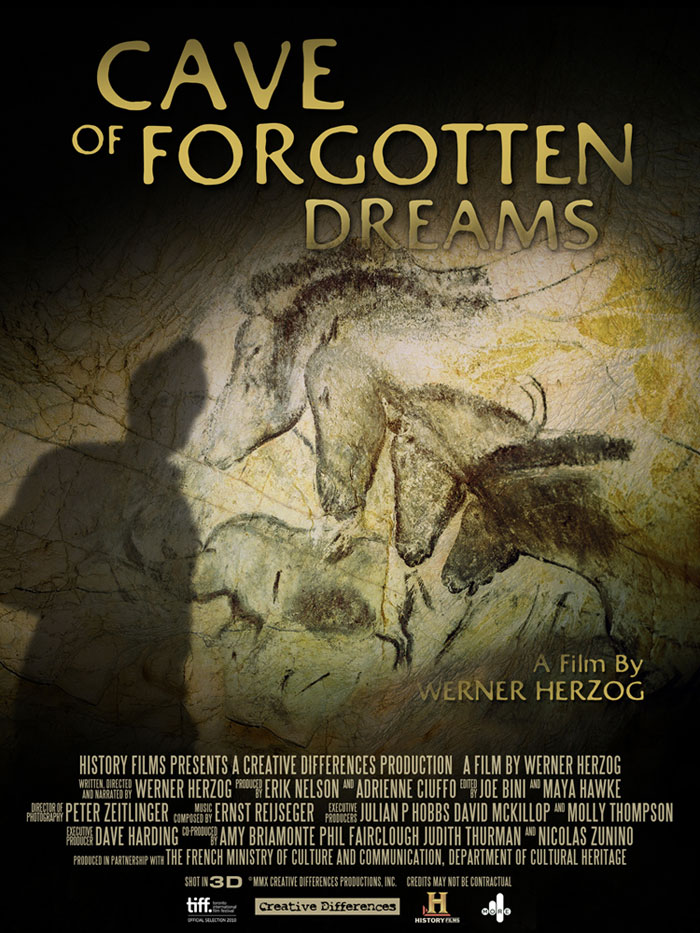

A 2008 New Yorker article by Judith Thurman caught the eye of noted German mad genius Werner Herzog, who petitioned the French government to take the very first (and almost certainly the very last) motion picture cameras ever permitted into the extremely fragile, pristine caves. Since not even the combined might of a national bureaucracy can stand in the way of Werner Herzog when he's made up his mind, he got his permission, and the result isCave of Forgotten Dreams, the director's first non-fiction film in three years, and his first work in 3-D (making it a rare, but not completely unknown, example of a 3-D documentary), and a film that is, at times, not nearly as aesthetically sophisticated as the best Herzog documentaries (e.g. Grizzly Man, Lessons of Darkness, Little Dieter Needs to Fly), rarely attempting to shake the fact that it was produced by the History Channel's theatrical arm; it makes up for this by being the best chance you or I or anyone outside of a tiny clutch of scientists will ever have to step inside what is arguably one of the most important sites on the planet. And "sophisticated" or not, the film has indisputably been put together with all the skill that can be brought to bear by one of our greatest living non-fiction filmmakers, who never makes any attempt to hide his nearly religious awe for the caves that he is so unthinkably lucky to be able to film.

The film is electrifying, no two ways about it. One can quibble or not about the various choices Herzog and his crew make in presenting the material, and the side-trips he makes, but the Chauvet cave itself is beyond reproach as a visual subject, both for its human-created artwork and the incredible loveliness of the cave itself, and the footage the four-man crew captured in that cave shows it off to extraordinary effect. Herzog is no lover of 3-D cinema, and has already promised that this will be his sole fling with the gimmicky new technology; but what a fling! Observing that the space of Chauvet is as much a component of the art as the content of the drawings, the director concluded that using a 3-D camera to capture the flow of that space was essential, and thus set about acquiring some special made cameras just for the occasion. These are not state-of-the-art machines; they are cheap prosumer camcorders given a makeover, and at times Cave of Forgotten Dreams explores a new paradigm in cinema: the 3-D Floating Video Noise effect. But for all that a shot here or there is unmistakably dodgy, when it matters the footage looks perfect, and the director's hunch paid off in spades: it really does add something to one's appreciation of the Chauvet art to see it this way. Not in some "you are there!" way - for the film, if anything, makes it entirely clear just how much we are not there - but in terms of understanding how texture and shape add to the feeling the drawings produce in the viewer. Meanwhile, the quick 'n dirty lighting, done mostly by Herzog himself, illuminates the art without washing it out, adding a subjective, poetic sense - the director states flat-out that he is attempting to replicate the texture of firelight, as the original painters in the cave would have seen things.

That Romantic treatment of the subject at hand is with us at every moment in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which finds the frequently apocalyptic director in an unusually sentimental mood. Even the title comes from his repeated inquiries with several of the specialists studying the cave into the unanswerable question of what these ancient painters were thinking, why they created this work, how does it speak to their dreams and their reality? To their credit, most of the interview subjects aren't a little ruffled by this question, which ends up creating a far more introspective and nuanced work than it might sound. Yes, the film tends to be hokey far more often than the typical Herzog film, what with the director suggesting (in what feels a hell of a lot like dry self-parody) that the Chauvet paintings's illusion of movement represents a form of proto-cinema, and that his film is thus the super-cutting-edge heir to the work down tens of thousands of years ago, and later turning his camera (mounted on a toy helicopter!) to the staggeringly dramatic Pont d'Arc over the Ardèche river, in the vicinity of the caves, and suggesting that there is an inherently operatic quality to the landscape, and the Chauvet artists are also the direct ancestors of Richard Wagner. And that is to say nothing of the Ernst Reijseger score, easy to adore and easy to find horribly distracting, which attempts gamely to recreate the idea of primitive music through hyper-modernism; with elements of religious chorale music omnipresent, it can't be accused of subtlety, and even though I for one thought it added a certain epic texture that the film didn't altogether need, I can never fault the viewer who finds it blaring and noisome.

We forgive these things because he is Werner Herzog; and yet we also forgive them because in a certain cockeyed way they make sense. The 3-D footage of the caves already produces a rather weird mood: the added depth gives us a better feeling for the structure of the artwork, but it also, in cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger's nervy framing, seems almost like a dream itself (it's something one notes without thinking about it that 3-D movies tend to look over-real, not realistic; you don't tend to notice in daily life that everything you look at is in 3-D, but by God, you notice in a stereoscopic movie. Herzog and Zeitlinger play with that to good effect). One only imagines how transportive the actual caves must be, when mere film footage of them is thus disorienting; so when Herzog, with his intensely soothing, hypnotic voice, narrates all sorts of odd things, it all fits in place in some otherworldly way.

In the end, the film ends up being about the evolution of art, as much as it is about documenting the caves; Herzog's emphasis on the film's own creation is fascinating of itself, but also serves to ground the physical fact of the movie alongside the physical fact of the caves. The director also had the chance to interview the discoverers of some artifacts discovered in the fall of 2008 in Germany, including a statue that is the oldest piece of representational art known to archaeology, at some 40,000 years old, finding in it some of the same motifs that drove the Chauvet paintings. And then it ends up being about the evolution of culture more generally, as Herzog's interviews a perfumier to discuss the scent of the caves, or has one of the Chauvet scientists stage a demonstration of Stone Age spear technology (in an apparent parody of the inherent gimmickry of the 3-D process), or, in the film's insistently Herzogian coda, spending time with the albino crocodiles swimming in a biosphere several miles from the cave, the jungle-like climate created from the run-off of nearby nuclear plants (which feels like more self-parody, and doesn't really fit the movie, though I can't shake the feeling that the film would be worse off without this coda).

But mostly, it's about the caves: how beautiful they are in the abstract, and how they communicate to us as human beings - and Herzog is always quick to remind us that we are, though separated by a gulf of time and culture, still the same animals that created these works in the first place. That's what lets him get away with all his loopy discursions, I think; by emphasising that the paintings were made by thinking, feeling, spiritual human beings, the film invites us to consider how we are still thinking, feeling, spiritual human beings, and from Wagner to nuclear mutant crocs, the film is always concerned with underling its central point, that creativity is always an act of dreaming. Awkwardly expressed at moments, perhaps, but it's a touching and transporting movie, and I wouldn't give it away for anything.

A 2008 New Yorker article by Judith Thurman caught the eye of noted German mad genius Werner Herzog, who petitioned the French government to take the very first (and almost certainly the very last) motion picture cameras ever permitted into the extremely fragile, pristine caves. Since not even the combined might of a national bureaucracy can stand in the way of Werner Herzog when he's made up his mind, he got his permission, and the result isCave of Forgotten Dreams, the director's first non-fiction film in three years, and his first work in 3-D (making it a rare, but not completely unknown, example of a 3-D documentary), and a film that is, at times, not nearly as aesthetically sophisticated as the best Herzog documentaries (e.g. Grizzly Man, Lessons of Darkness, Little Dieter Needs to Fly), rarely attempting to shake the fact that it was produced by the History Channel's theatrical arm; it makes up for this by being the best chance you or I or anyone outside of a tiny clutch of scientists will ever have to step inside what is arguably one of the most important sites on the planet. And "sophisticated" or not, the film has indisputably been put together with all the skill that can be brought to bear by one of our greatest living non-fiction filmmakers, who never makes any attempt to hide his nearly religious awe for the caves that he is so unthinkably lucky to be able to film.

The film is electrifying, no two ways about it. One can quibble or not about the various choices Herzog and his crew make in presenting the material, and the side-trips he makes, but the Chauvet cave itself is beyond reproach as a visual subject, both for its human-created artwork and the incredible loveliness of the cave itself, and the footage the four-man crew captured in that cave shows it off to extraordinary effect. Herzog is no lover of 3-D cinema, and has already promised that this will be his sole fling with the gimmicky new technology; but what a fling! Observing that the space of Chauvet is as much a component of the art as the content of the drawings, the director concluded that using a 3-D camera to capture the flow of that space was essential, and thus set about acquiring some special made cameras just for the occasion. These are not state-of-the-art machines; they are cheap prosumer camcorders given a makeover, and at times Cave of Forgotten Dreams explores a new paradigm in cinema: the 3-D Floating Video Noise effect. But for all that a shot here or there is unmistakably dodgy, when it matters the footage looks perfect, and the director's hunch paid off in spades: it really does add something to one's appreciation of the Chauvet art to see it this way. Not in some "you are there!" way - for the film, if anything, makes it entirely clear just how much we are not there - but in terms of understanding how texture and shape add to the feeling the drawings produce in the viewer. Meanwhile, the quick 'n dirty lighting, done mostly by Herzog himself, illuminates the art without washing it out, adding a subjective, poetic sense - the director states flat-out that he is attempting to replicate the texture of firelight, as the original painters in the cave would have seen things.

That Romantic treatment of the subject at hand is with us at every moment in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which finds the frequently apocalyptic director in an unusually sentimental mood. Even the title comes from his repeated inquiries with several of the specialists studying the cave into the unanswerable question of what these ancient painters were thinking, why they created this work, how does it speak to their dreams and their reality? To their credit, most of the interview subjects aren't a little ruffled by this question, which ends up creating a far more introspective and nuanced work than it might sound. Yes, the film tends to be hokey far more often than the typical Herzog film, what with the director suggesting (in what feels a hell of a lot like dry self-parody) that the Chauvet paintings's illusion of movement represents a form of proto-cinema, and that his film is thus the super-cutting-edge heir to the work down tens of thousands of years ago, and later turning his camera (mounted on a toy helicopter!) to the staggeringly dramatic Pont d'Arc over the Ardèche river, in the vicinity of the caves, and suggesting that there is an inherently operatic quality to the landscape, and the Chauvet artists are also the direct ancestors of Richard Wagner. And that is to say nothing of the Ernst Reijseger score, easy to adore and easy to find horribly distracting, which attempts gamely to recreate the idea of primitive music through hyper-modernism; with elements of religious chorale music omnipresent, it can't be accused of subtlety, and even though I for one thought it added a certain epic texture that the film didn't altogether need, I can never fault the viewer who finds it blaring and noisome.

We forgive these things because he is Werner Herzog; and yet we also forgive them because in a certain cockeyed way they make sense. The 3-D footage of the caves already produces a rather weird mood: the added depth gives us a better feeling for the structure of the artwork, but it also, in cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger's nervy framing, seems almost like a dream itself (it's something one notes without thinking about it that 3-D movies tend to look over-real, not realistic; you don't tend to notice in daily life that everything you look at is in 3-D, but by God, you notice in a stereoscopic movie. Herzog and Zeitlinger play with that to good effect). One only imagines how transportive the actual caves must be, when mere film footage of them is thus disorienting; so when Herzog, with his intensely soothing, hypnotic voice, narrates all sorts of odd things, it all fits in place in some otherworldly way.

In the end, the film ends up being about the evolution of art, as much as it is about documenting the caves; Herzog's emphasis on the film's own creation is fascinating of itself, but also serves to ground the physical fact of the movie alongside the physical fact of the caves. The director also had the chance to interview the discoverers of some artifacts discovered in the fall of 2008 in Germany, including a statue that is the oldest piece of representational art known to archaeology, at some 40,000 years old, finding in it some of the same motifs that drove the Chauvet paintings. And then it ends up being about the evolution of culture more generally, as Herzog's interviews a perfumier to discuss the scent of the caves, or has one of the Chauvet scientists stage a demonstration of Stone Age spear technology (in an apparent parody of the inherent gimmickry of the 3-D process), or, in the film's insistently Herzogian coda, spending time with the albino crocodiles swimming in a biosphere several miles from the cave, the jungle-like climate created from the run-off of nearby nuclear plants (which feels like more self-parody, and doesn't really fit the movie, though I can't shake the feeling that the film would be worse off without this coda).

But mostly, it's about the caves: how beautiful they are in the abstract, and how they communicate to us as human beings - and Herzog is always quick to remind us that we are, though separated by a gulf of time and culture, still the same animals that created these works in the first place. That's what lets him get away with all his loopy discursions, I think; by emphasising that the paintings were made by thinking, feeling, spiritual human beings, the film invites us to consider how we are still thinking, feeling, spiritual human beings, and from Wagner to nuclear mutant crocs, the film is always concerned with underling its central point, that creativity is always an act of dreaming. Awkwardly expressed at moments, perhaps, but it's a touching and transporting movie, and I wouldn't give it away for anything.

Categories: documentaries, the third dimension, werner herzog