Killer style

The ad campaign for Hanna does something new in my experience: it credits the composers of the score as prominently as the director and almost as prominently as the actors. This is not unjustified, for Hanna is almost exclusively a grand experiment in surface style, an attempt to distract the viewer for almost two solid hours with absolutely nothing but urgency - urgency about what? Who gives a shit! It's urgent! - and the score, composed by electronica duo The Chemical Brothers, is perhaps the most effective element behind that all-encompassing urgent feeling. But let me return to that presently.

The Hanna of Hanna is a teenage girl, played by Saoirse Ronan (whose peculiar failure to break out as a major young star remains puzzling to me - I hope it's not because she has standards or class or wants a normal life, or any damn bullshit like that), who lives in a snowbound forest with her father, Erik Heller (Eric Bana). Here she has been trained in the fine arts of survival - the first thing we see her do is kill a reindeer with an arrow, and then putting it out of its misery with a pistol - and combat, and languages, and all the sorts of things that would make a little girl a genius warrior and spy, but not necessarily a particularly functional human being.

The reason is that Heller is himself a warrior and a spy, late of the CIA, and his training has been directed to the end of making Hanna his tool in revenge against his old handler, Marissa Wiegler (Cate Blanchett, a broadly hammy villainous turn that ranks among the worst performances in her career. Seriously, it's Elizabeth: Armed & Fabulous bad). Or maybe it's just so that Hanna will be able to remain safe if Wiegler ever comes a-knockin'. The relationship between these three characters is not smoothed out anytime soon, and though it's almost completely predictable, I guess the nice thing to do is not to spoil the plot, especially when the slow reveal of Hanna's backstory is virtually the only story Hanna tells, since the legitimate in-the-present narrative consists of virtually nothing but an extended chase scene from the Arctic Circle to Morocco to Germany.

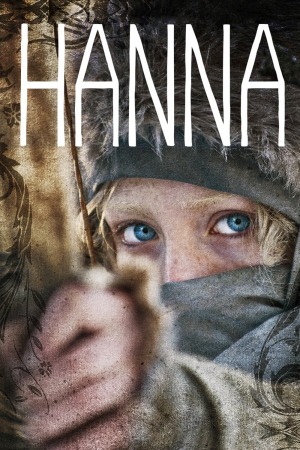

Superfically, and "superficially" is a really great adverb to keep in your pocket when you're talking about Hanna, the film looks like it could be the latest in the disquieting subgenre of teen girls killing people in sometimes very brutal ways, typified by the indifferently nihilistic Kick-Ass. But a fairly huge gulf separates Hanna from Kick-Ass, and it has at least something to do with Ronan, whose performance does not suggest a precocious sociopath, nor does it admit any sexualised violence. With her blank face, uncomfortably white skin (bleached out even farther by cinematographer Alwin H. Küchler, who pours the light of what appears to be a small star on the actress), watery eyes, and a mock-German accent that almost but not quite sounds like the real voice of a real human being, Ronan mostly seems to suggest something entirely if subtly not human, more like a teeny tiny Tilda Swinton or adolescent Björk than the fetishistic "hot teen with a gun" of pop culture.

Ronan's Hanna does not just remain unknown to us, she is inherently unknowable, and there are good enough reasons for that in the script that it's not just weak storytelling; but it does say a lot about the film's priorities that the main character is by design so wholly opaque throughout the whole affair (the film's flattest scenes are ones in the middle, where Hanna, hiding with a family of British tourists, tries to go on a double date; it's the one place where the film turns into the culture-clash pseudocomedy that "little girl raised in the woods to be a killer" could so easily become, and it's also the most boring part of the movie). I'm hard-pressed to believe that's all from the script by David Farr and Seth Lochhead, given that Lochhead's original version made the Black List of the industry's best-loved unproduced screenplays twice. Far easier to... credit? blame? director Joe Wright, making his fourth feature in a career that has definitively sided with flash over substance every time the two came into conflict. This is a director who, in Atonement, thought that the best way to depict the bloody aftermath of combat was by means of a gigantic tracking shot assembled in such a way that it was virtually impossible not to notice, first and foremost, that we were watching one hell of an ambitious tracking shot.

That "let us first attend to what is visually impressive, and to the human element only second" impulse works better in Hanna, which is about a fictitious assassin girl who mostly only kills people that deserve it, than it did in a film about an actual real-life war where actual real-life people died; also because action thrillers are inherently more surface-level affairs than character dramas are. And if Hanna is all surfaces, Wright at least has the basic decency to make sure the surfaces gleam. His established love of tracking shots that are harder than they need to be is in full evidence in a fistfight between Bana and some thugs in a Berlin U-Bahn station; he and regular production designer Sarah Greenwood craft all sorts of unabashedly movie set locations that are nevertheless eye candy of the best sort, from a CIA facility that's all ovoid walls and dark steel floors, a last gasp of '20s-style Expressionism mixed with the grimiest sci-fi film you can imagine, all the way to a Brothers Grimm theme park that pound us over the head with the fairy tale imagery that has been indiscriminately scattered throughout the film (Heller's one concession to Hanna's childhood appears to be a book of folklore), but at this point subtlety is not on the film's list of interests, and sometimes the ludicrously overdetermined is just as effective as the cunning and refined.

Back then we come to The Chemical Brothers. The thing about the score is, Joe Wright knows. We can tell from the incredible privilege of place given to the scene where Hanna asks her dad about the definition of "music" that music will be important (hence, for example, the otherwise inscrutable scene where Hanna watches, and watches, a dancer in Spain). We can tell even more from the way that the film withholds any trace of an underscore until the scene where Wiegler's sp00ks find the cabin where Hanna lives and Heller has just escaped, turning the paced story of a young woman in a fairy tale into a pound-pound-pound spy thriller, and then we hear the first insinuating beats of music, saying as clearly as anything could, "aw,hell yeah..." The score is a thing, alright, from sexy, slinky rhythms that could double in a German disco as easily as follow scenes of Ronan darting back and forth between impeccably-framed crates on a loading dock, over to lurking thumps that barely even deserve the word "melody", just squatting like an ugly toad and glowering at the audience, reminding us of the crushing institutional threat of the CIA.

The film has not a blasted thing to say, and it adds up to a big spoonful of fuck-all (right down to a magnificently arbitrary non-ending), but it manages to kick off a phenomenal adrenaline rush and look damn gorgeous doing it. I suppose I am essentially praising Hanna for being a drug, and not a movie, and that's not a direction I like to see cinema heading; but at least the comedown is gentle. Sucker Punch is still in theaters, y'all.

7/10

The Hanna of Hanna is a teenage girl, played by Saoirse Ronan (whose peculiar failure to break out as a major young star remains puzzling to me - I hope it's not because she has standards or class or wants a normal life, or any damn bullshit like that), who lives in a snowbound forest with her father, Erik Heller (Eric Bana). Here she has been trained in the fine arts of survival - the first thing we see her do is kill a reindeer with an arrow, and then putting it out of its misery with a pistol - and combat, and languages, and all the sorts of things that would make a little girl a genius warrior and spy, but not necessarily a particularly functional human being.

The reason is that Heller is himself a warrior and a spy, late of the CIA, and his training has been directed to the end of making Hanna his tool in revenge against his old handler, Marissa Wiegler (Cate Blanchett, a broadly hammy villainous turn that ranks among the worst performances in her career. Seriously, it's Elizabeth: Armed & Fabulous bad). Or maybe it's just so that Hanna will be able to remain safe if Wiegler ever comes a-knockin'. The relationship between these three characters is not smoothed out anytime soon, and though it's almost completely predictable, I guess the nice thing to do is not to spoil the plot, especially when the slow reveal of Hanna's backstory is virtually the only story Hanna tells, since the legitimate in-the-present narrative consists of virtually nothing but an extended chase scene from the Arctic Circle to Morocco to Germany.

Superfically, and "superficially" is a really great adverb to keep in your pocket when you're talking about Hanna, the film looks like it could be the latest in the disquieting subgenre of teen girls killing people in sometimes very brutal ways, typified by the indifferently nihilistic Kick-Ass. But a fairly huge gulf separates Hanna from Kick-Ass, and it has at least something to do with Ronan, whose performance does not suggest a precocious sociopath, nor does it admit any sexualised violence. With her blank face, uncomfortably white skin (bleached out even farther by cinematographer Alwin H. Küchler, who pours the light of what appears to be a small star on the actress), watery eyes, and a mock-German accent that almost but not quite sounds like the real voice of a real human being, Ronan mostly seems to suggest something entirely if subtly not human, more like a teeny tiny Tilda Swinton or adolescent Björk than the fetishistic "hot teen with a gun" of pop culture.

Ronan's Hanna does not just remain unknown to us, she is inherently unknowable, and there are good enough reasons for that in the script that it's not just weak storytelling; but it does say a lot about the film's priorities that the main character is by design so wholly opaque throughout the whole affair (the film's flattest scenes are ones in the middle, where Hanna, hiding with a family of British tourists, tries to go on a double date; it's the one place where the film turns into the culture-clash pseudocomedy that "little girl raised in the woods to be a killer" could so easily become, and it's also the most boring part of the movie). I'm hard-pressed to believe that's all from the script by David Farr and Seth Lochhead, given that Lochhead's original version made the Black List of the industry's best-loved unproduced screenplays twice. Far easier to... credit? blame? director Joe Wright, making his fourth feature in a career that has definitively sided with flash over substance every time the two came into conflict. This is a director who, in Atonement, thought that the best way to depict the bloody aftermath of combat was by means of a gigantic tracking shot assembled in such a way that it was virtually impossible not to notice, first and foremost, that we were watching one hell of an ambitious tracking shot.

That "let us first attend to what is visually impressive, and to the human element only second" impulse works better in Hanna, which is about a fictitious assassin girl who mostly only kills people that deserve it, than it did in a film about an actual real-life war where actual real-life people died; also because action thrillers are inherently more surface-level affairs than character dramas are. And if Hanna is all surfaces, Wright at least has the basic decency to make sure the surfaces gleam. His established love of tracking shots that are harder than they need to be is in full evidence in a fistfight between Bana and some thugs in a Berlin U-Bahn station; he and regular production designer Sarah Greenwood craft all sorts of unabashedly movie set locations that are nevertheless eye candy of the best sort, from a CIA facility that's all ovoid walls and dark steel floors, a last gasp of '20s-style Expressionism mixed with the grimiest sci-fi film you can imagine, all the way to a Brothers Grimm theme park that pound us over the head with the fairy tale imagery that has been indiscriminately scattered throughout the film (Heller's one concession to Hanna's childhood appears to be a book of folklore), but at this point subtlety is not on the film's list of interests, and sometimes the ludicrously overdetermined is just as effective as the cunning and refined.

Back then we come to The Chemical Brothers. The thing about the score is, Joe Wright knows. We can tell from the incredible privilege of place given to the scene where Hanna asks her dad about the definition of "music" that music will be important (hence, for example, the otherwise inscrutable scene where Hanna watches, and watches, a dancer in Spain). We can tell even more from the way that the film withholds any trace of an underscore until the scene where Wiegler's sp00ks find the cabin where Hanna lives and Heller has just escaped, turning the paced story of a young woman in a fairy tale into a pound-pound-pound spy thriller, and then we hear the first insinuating beats of music, saying as clearly as anything could, "aw,

The film has not a blasted thing to say, and it adds up to a big spoonful of fuck-all (right down to a magnificently arbitrary non-ending), but it manages to kick off a phenomenal adrenaline rush and look damn gorgeous doing it. I suppose I am essentially praising Hanna for being a drug, and not a movie, and that's not a direction I like to see cinema heading; but at least the comedown is gentle. Sucker Punch is still in theaters, y'all.

7/10

Categories: action, gorgeous cinematography, spy films, thrillers