Female problems

I have no particular frame to put around Jason Dolha's review request for the Carry On Campaign: he asked me to take a look at one of the most unnerving psychological thrillers ever put to film, and I was pretty much ecstatic to do it, even if it took me forever and then some to actually get around to writing the damn thing.

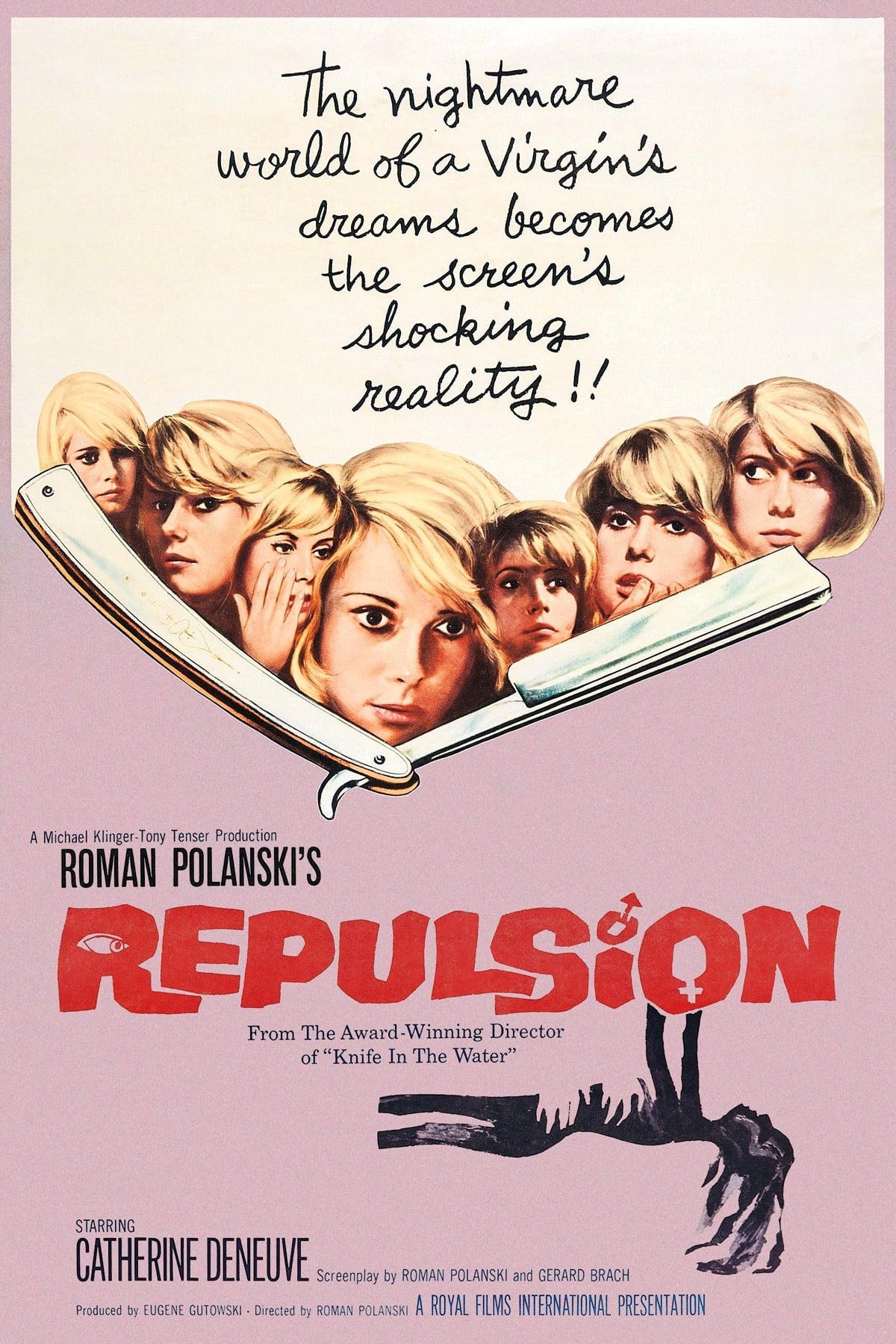

The 1965 horror classic >Repulsion is British production by a Franco-Polish director, headlined by an up-and-coming French starlet, with a hallucinatory visual scheme that's equal parts Eastern European surrealism and Italian phantasmagoria. A combination that could only come about in the '60s, and really, every element of the film is so utterly perfect for its instant in the Zeitgeist, at the very heart of the explosion of continental cosmopolitanism and right at the cusp of the sexual revolution, that one could almost say that the film had to be, out of cultural necessity - s'il n'existait pas, il faudrait l'inventer. And yet, director and co-writer Roman Polanski didn't see it that way at all, conceiving Repulsion with writing partner Gérard Brach (who would continue to collaborate with Polanski into the '90s) as a "one for them" commercial throwaway that would finance the writers' dream project, the pointedly difficult Cul-de-sac.

No matter; we have Repulsion, and that is what matters. It's not without its flaws, of course - a laggy second quarter, and a view of female psychology that's emblematic of the filmmaker's, let us be polite and call it a "difficult" understanding of women - but gorgeously well-crafted, marrying the artistic maturity of cinema made for discerning intellectuals (whatever the hell the called "the arthouse" back in the '60s) with the grottiness of genre film, just about the same time that the Italians, led by Mario Bava, began to pursue that marriage with any particular enthusiasm. It's an early mindfuck movie made for an audience demanding more from its mindfuckery than just a good sense of Cool, and it remains one of the most effectively nasty thrillers about going mad put to film.

Like a great many top-notch horror films, the story of Repulsion doesn't get much more detailed no matter how closely we look at the detail. It's chiefly about a young woman who is confused and scared by sex being left alone for the week in an empty apartment she ordinarily shares with her older, more worldly sister; as the week progresses, the woman slips further and further into a psychotic fantasia where the very apartment becomes a masculine entity trying to force itself on her, and woe betide the few actual real-world men who cross paths with her during this time. That's all there is to a plot; everything else is just mood-setting.

The woman who feels so repulsed by the male sex is a Belgian immigrant to London, Carole, played by Catherine Deneuve, the future goddess of world cinema who at that point had only one major international hit to her credit, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. This very film did a great deal to solidify her stardom and establish a persona that would serve the actress well for some years, but even coming to the performance blind, as most English-speaking viewers would have when the film was new, it's clear that there's something essential to Carole that only Deneuve could supply: a tension between her sexpot good looks on the one hand (she'd already made films, and a son, with famed sexploitation artist Roger Vadim), and an icy sexual unavailability on the other (not that Deneuve made a career out of playing ice queens, though she at times had that reputation, but that the other '60s sex icons in European cinema lacked her skills as an actress to milk that tension for all it was worth). She was a woman you couldn't help wanting to fuck, in other words, even though she all but had a "No Touching!" sign hanging around her neck, and it's that conflict which drives the psycho-sexual nightmares of Repulsion.

If that makes it sound like a movie for boys even though its plot is primarily concerned with charting the inner mind of a woman... it absolutely is. Carole is at all points in the movie viewed from the outside, made an object of study by Polanski and director of photography Gilbert Taylor's camera, rather than subjectively made the audience's surrogate. This sounds like, and perhaps is, a complaint, although the use of perspective is actually one of the most effective things about Repulsion: even if the film's point-of-view is never, ever Carole's it's also plainly not the case that the film has an omniscient, third-person point-of-view either; one of the most striking things about the film, in fact, is just how damn subjective the visuals are, without any character seeming to be the focus of that subjectivity. At times the camera mimics, with unsettling literalness, the act of craning your head around to get a better view; at one point early on, a tracking shot stops abruptly and loops back to take a look at a character we just walked past; but this is never meant to replicate the perspective of anyone in the film. Even late in the movie, when there are a few cuts to what look for all the world like POV shots, it quickly becomes clear from the specifics of the camera placement that we can't be in the same position as the character we expected to be aligned with in that moment. The perspective of Repulsion is maybe that of the voyeur, someone peering in at Carole without ever being noticed - at once an exemplar of the Male Gaze and a satire of the same. Whatever the heck is going on, its smashingly wonderful at creating a dislocated sense of what we're looking at; a terrific exercise in tweaking the audience that is 100% Polanski (he would use refined versions of some of the very same tricks in Rosemary's Baby), already a master of manipulating cinema to suit his own neurotic sense of uneasiness on only his second feature.

Again, though, none of this privilege's Carole's perspective, which leads me to the other great thing Repulsion does to fuck with our sense of what's going on: for even though our vision is never aligned with Carole's, our reality is - and her reality is a tremendously warped place, with cracks appearing all over the walls of the apartment hands bursting out of the hallway to grab at her breasts, surfaces turning into clay as she leans against them, and a man who appears from nowhere to rape her, in some of the most unnerving scenes in the movie (it's not clear - at all - how much these fantasies are a blend of horror and desire). This is all strictly the stuff of surrealist horror, but the film has done such a great job of divorcing our viewpoint from the protagonist's that by the time the really weird stuff starts to happen, we're not expecting a subjective reality at all, and the breakdown of Carole's mental state ends doesn't end up reading as hallucination. It's a sick trick to play on the audience, and it's most of the reason why Repulsion ends up being so uncanny and potent. Indeed, so completely does Polanski manage to screw with our understanding of what is or isn't happening, that when SPOILER WARNING FOR REST OF PARAGRAPH Carole ends up killing two men, including the handsome, stalkery suitor who's been bothering her since the beginning, it's hard to say whether she really did anything of the sort, and it's not until the last scene that we get any kind of solid confirmation.

Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby, and The Tenant are often loosely linked as Polanski's "Apartment Trilogy", scary films about the life of urban renters. That's a fun notion, though rather beholden to the tendency of cinephiles and marketing men to think in threes; Rosemary's Baby isn't quite a fit with the others, being as it is a paranormal horror movie pretending for much of its running time to be a psychological thriller, and with a much less overt sexual component than Repulsion and The Tenant, both of which center on a paranoid neurotic externalising his or her belief that everyone else is a predator. But even The Tenant, which ends with the protagonist (played by Polanski himself) in drag, is a far less sexual film than Repulsion, which rather uncomfortably advances the argument that Carole would be sane and normal if only she wasn't so put off by the thought of having sex with men. The first lines, practically, are the accusation that Carole is absent-minded because she's in love, and the final shot practically dares us not to assume that there's some deep dark secret involving sexual abuse in her past (though it cleverly refuses to insist on that reading at all); the most obvious visual signpost of time passing in Carole's private hell is the increasingly rotted state of a rabbit carcass from the butcher, a metaphor for her failings as a housekeeper even as it's a hell of a visceral way to grab our attention over and over again.

Still and all, even if Repulsion is stating out loud that Carole's problem is hysteria in its most denotative sense, the experience of the film is never so overt as that. It's far too terrifying being caught in the periphery of Carole's madness to wonder, in the moment, if that madness is the side effect of her owning a vagina; Polanski's command of the medium was already so complete in 1965 - and by my lights, Repulsion remains one of the most completely effective movies of his entire career - that his feature is first and above all about the shock of the moment, communicating the sheer, visceral awfulness of a quick slide into madness with such nihilistic delight that the question of why that slide into madness is honestly never all that pressing. As psychological horror films go, there are more than a few that get the psychology better than this, but almost none that come within spitting distance of the horror.

The 1965 horror classic >Repulsion is British production by a Franco-Polish director, headlined by an up-and-coming French starlet, with a hallucinatory visual scheme that's equal parts Eastern European surrealism and Italian phantasmagoria. A combination that could only come about in the '60s, and really, every element of the film is so utterly perfect for its instant in the Zeitgeist, at the very heart of the explosion of continental cosmopolitanism and right at the cusp of the sexual revolution, that one could almost say that the film had to be, out of cultural necessity - s'il n'existait pas, il faudrait l'inventer. And yet, director and co-writer Roman Polanski didn't see it that way at all, conceiving Repulsion with writing partner Gérard Brach (who would continue to collaborate with Polanski into the '90s) as a "one for them" commercial throwaway that would finance the writers' dream project, the pointedly difficult Cul-de-sac.

No matter; we have Repulsion, and that is what matters. It's not without its flaws, of course - a laggy second quarter, and a view of female psychology that's emblematic of the filmmaker's, let us be polite and call it a "difficult" understanding of women - but gorgeously well-crafted, marrying the artistic maturity of cinema made for discerning intellectuals (whatever the hell the called "the arthouse" back in the '60s) with the grottiness of genre film, just about the same time that the Italians, led by Mario Bava, began to pursue that marriage with any particular enthusiasm. It's an early mindfuck movie made for an audience demanding more from its mindfuckery than just a good sense of Cool, and it remains one of the most effectively nasty thrillers about going mad put to film.

Like a great many top-notch horror films, the story of Repulsion doesn't get much more detailed no matter how closely we look at the detail. It's chiefly about a young woman who is confused and scared by sex being left alone for the week in an empty apartment she ordinarily shares with her older, more worldly sister; as the week progresses, the woman slips further and further into a psychotic fantasia where the very apartment becomes a masculine entity trying to force itself on her, and woe betide the few actual real-world men who cross paths with her during this time. That's all there is to a plot; everything else is just mood-setting.

The woman who feels so repulsed by the male sex is a Belgian immigrant to London, Carole, played by Catherine Deneuve, the future goddess of world cinema who at that point had only one major international hit to her credit, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. This very film did a great deal to solidify her stardom and establish a persona that would serve the actress well for some years, but even coming to the performance blind, as most English-speaking viewers would have when the film was new, it's clear that there's something essential to Carole that only Deneuve could supply: a tension between her sexpot good looks on the one hand (she'd already made films, and a son, with famed sexploitation artist Roger Vadim), and an icy sexual unavailability on the other (not that Deneuve made a career out of playing ice queens, though she at times had that reputation, but that the other '60s sex icons in European cinema lacked her skills as an actress to milk that tension for all it was worth). She was a woman you couldn't help wanting to fuck, in other words, even though she all but had a "No Touching!" sign hanging around her neck, and it's that conflict which drives the psycho-sexual nightmares of Repulsion.

If that makes it sound like a movie for boys even though its plot is primarily concerned with charting the inner mind of a woman... it absolutely is. Carole is at all points in the movie viewed from the outside, made an object of study by Polanski and director of photography Gilbert Taylor's camera, rather than subjectively made the audience's surrogate. This sounds like, and perhaps is, a complaint, although the use of perspective is actually one of the most effective things about Repulsion: even if the film's point-of-view is never, ever Carole's it's also plainly not the case that the film has an omniscient, third-person point-of-view either; one of the most striking things about the film, in fact, is just how damn subjective the visuals are, without any character seeming to be the focus of that subjectivity. At times the camera mimics, with unsettling literalness, the act of craning your head around to get a better view; at one point early on, a tracking shot stops abruptly and loops back to take a look at a character we just walked past; but this is never meant to replicate the perspective of anyone in the film. Even late in the movie, when there are a few cuts to what look for all the world like POV shots, it quickly becomes clear from the specifics of the camera placement that we can't be in the same position as the character we expected to be aligned with in that moment. The perspective of Repulsion is maybe that of the voyeur, someone peering in at Carole without ever being noticed - at once an exemplar of the Male Gaze and a satire of the same. Whatever the heck is going on, its smashingly wonderful at creating a dislocated sense of what we're looking at; a terrific exercise in tweaking the audience that is 100% Polanski (he would use refined versions of some of the very same tricks in Rosemary's Baby), already a master of manipulating cinema to suit his own neurotic sense of uneasiness on only his second feature.

Again, though, none of this privilege's Carole's perspective, which leads me to the other great thing Repulsion does to fuck with our sense of what's going on: for even though our vision is never aligned with Carole's, our reality is - and her reality is a tremendously warped place, with cracks appearing all over the walls of the apartment hands bursting out of the hallway to grab at her breasts, surfaces turning into clay as she leans against them, and a man who appears from nowhere to rape her, in some of the most unnerving scenes in the movie (it's not clear - at all - how much these fantasies are a blend of horror and desire). This is all strictly the stuff of surrealist horror, but the film has done such a great job of divorcing our viewpoint from the protagonist's that by the time the really weird stuff starts to happen, we're not expecting a subjective reality at all, and the breakdown of Carole's mental state ends doesn't end up reading as hallucination. It's a sick trick to play on the audience, and it's most of the reason why Repulsion ends up being so uncanny and potent. Indeed, so completely does Polanski manage to screw with our understanding of what is or isn't happening, that when SPOILER WARNING FOR REST OF PARAGRAPH Carole ends up killing two men, including the handsome, stalkery suitor who's been bothering her since the beginning, it's hard to say whether she really did anything of the sort, and it's not until the last scene that we get any kind of solid confirmation.

Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby, and The Tenant are often loosely linked as Polanski's "Apartment Trilogy", scary films about the life of urban renters. That's a fun notion, though rather beholden to the tendency of cinephiles and marketing men to think in threes; Rosemary's Baby isn't quite a fit with the others, being as it is a paranormal horror movie pretending for much of its running time to be a psychological thriller, and with a much less overt sexual component than Repulsion and The Tenant, both of which center on a paranoid neurotic externalising his or her belief that everyone else is a predator. But even The Tenant, which ends with the protagonist (played by Polanski himself) in drag, is a far less sexual film than Repulsion, which rather uncomfortably advances the argument that Carole would be sane and normal if only she wasn't so put off by the thought of having sex with men. The first lines, practically, are the accusation that Carole is absent-minded because she's in love, and the final shot practically dares us not to assume that there's some deep dark secret involving sexual abuse in her past (though it cleverly refuses to insist on that reading at all); the most obvious visual signpost of time passing in Carole's private hell is the increasingly rotted state of a rabbit carcass from the butcher, a metaphor for her failings as a housekeeper even as it's a hell of a visceral way to grab our attention over and over again.

Still and all, even if Repulsion is stating out loud that Carole's problem is hysteria in its most denotative sense, the experience of the film is never so overt as that. It's far too terrifying being caught in the periphery of Carole's madness to wonder, in the moment, if that madness is the side effect of her owning a vagina; Polanski's command of the medium was already so complete in 1965 - and by my lights, Repulsion remains one of the most completely effective movies of his entire career - that his feature is first and above all about the shock of the moment, communicating the sheer, visceral awfulness of a quick slide into madness with such nihilistic delight that the question of why that slide into madness is honestly never all that pressing. As psychological horror films go, there are more than a few that get the psychology better than this, but almost none that come within spitting distance of the horror.