Death in the family

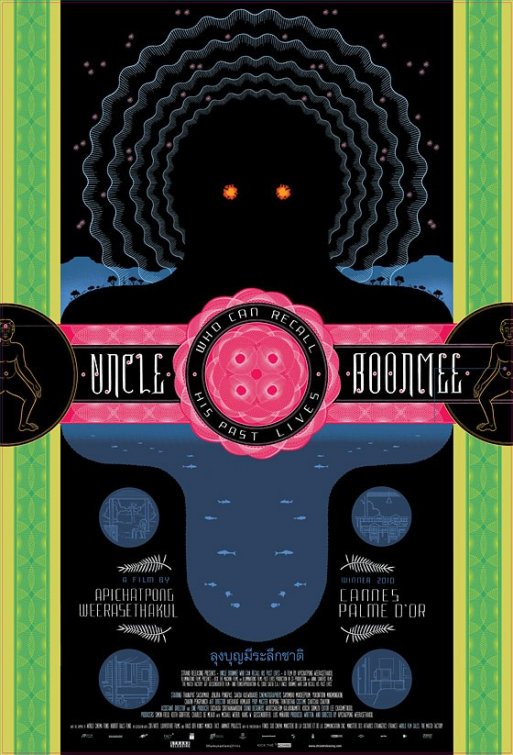

Despite its gloriously fervid title, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (winner of the 2010 Palme d'Or, mainstay of last fall's festival season, but some of us just didn't get to be the cool kids last year) strikes me as being the most mainstream, I daresay normal, film yet made by Thailand's reigning superstar director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, darling of a certain clique of the arthouse set that I happen to belong to. Note, however, that "mainstream" and "normal" are words that can have either concrete meanings, or relative meanings, and in the particular case of Uncle Boonmee, I use them both in a spectacularly relative way.

The film relates the final days of a plantation owner, Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar), dying of kidney failure. He is being visited by his sister-in-law, Jen (Jenjira Pongpas), and his nephew, Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee), wishing to bring him comfort in his last moments; but those aren't the only visitors. Death, it seems, attracts beings from the other world, and Boonmee also finds himself meeting up with the ghost of his wife, Huay (Natthakarn Aphaiwonk), and his long-lost soon Boonsong (Geerasak Kulhong), who many years ago chased a monkey ghost into the jungle, mated with her, and has now himself become a monkey ghost, with glowing red eyes and a pelt of jet black hair. For Boonmee, they are the memories of his past in this life; he's also receiving visions of what might be his lives before this one - though the film does not state that they must be - nor does it make it unmistakably clear that Boonmee, and not the audience, is the primary audience for these visions.

This might sound like a puzzle box movie, the kind which invites you to spend the next several days after you watch it figuring out what everything meant and how it all fits together. It might sound like that, but it most undoubtedly is not that. In keeping with Apichatpong's previous films, Uncle Boonmee always seems "about" the feeling and texture of individual scenes, and the overall laconic, even hypnotising mood of the whole experience, rather than about generating any particular "meaning", though I think that it's not hard to say, in the broad sense, that the film's themes are a fascination with the process of death (in a spiritual way, not a morbid one), and the regrets we have for our past. As much as he is obsessed with anything in particular, Boonmee is constantly preoccupied with karma: worried about punishment for the sins he committed in his youth as a soldier, curious about what he did in other lives that led, for good or ill, to this one. His dinner with his sister and nephew, and then with his ghostly wife and son as well (a scene that begins in a register of ineluctable creepiness and becomes quickly melancholic and surreal, once it becomes apparent that none of the three living people see any of this as peculiar in the slightest), the film's highest achievement, is primarily about nostalgia and remembrance, looking back and reflecting on all the steps between Then and Now.

In awarding the film its Cannes prize, jury president Tim Burton cited its creation of a dreamlike state, and as much of a cliché as the word "dreamy" is in describing any slow-moving art film with self-consciously anti-realistic elements, I've not been able to come up with a more apt description of Uncle Boonmee. Even more than Apichatpong's other films, which are equally slow-moving, meditative, and surreal, this plays like a somewhat disjointed series of hallucinations, right from its incredible opening sequence: several minutes of a cow being led through a jungle at night, bathed in shades of blue so dark it's nearly inscrutable, punctuated with a shot of a dark silhouette with glowing red eyes (a monkey ghost, we'll learn; but which monkey ghost? My first thought was that this figure might have been Boonmee in his past life, and the movie supports and does not support that reading to equal measure). Kind of the film to let us know in the opening minutes how it is to be watched: you have to give yourself over to the rhythms of the film completely, and not expect meaning to reveal itself except gradually, and invest yourself more in how each image, anchored by an omnipresent soundscape of natural noises, moves you. Perhaps that is what it's like to be near death, hyper-attuned to the small details of every moment; that is at any rate the feeling I got from Uncle Boonmee, that it encouraged an extremely reflective awareness of place and movement and color.

I did call this Apichatpong's "mainstream" film, didn't I? Yes, and only for this reason: compared to his earlier features, Blissfully Yours, Tropical Malady, and Syndromes and a Century, one does not get the same sense in Uncle Boonmee that the filmmaker is actively trying to destroy the medium of cinema and replace it with something more to his liking. For one thing, unlike the previous films, Uncle Boonmee does not break into two apparently irreconcilable parts; nor does it seriously challenge any particular aspect of film grammar, though viewers who find its beyond-glacial pace to be so much indulgent, pretentious fluff might not agree with me on that point exactly. In fact, compared to his previous work, it surprised me a little bit how easy it is to follow along what, specifically, happens in Uncle Boonmee: however inexplicable the import of any given event, it's never really confusing what events occur in what order.

Considering that, it's perhaps weird that, to me anyway, Uncle Boonmee ends up being the murkiest of Apichatpong's features. There's something about the contrast in emotions and sensations in each of the other three that adds up to an implicit whole, something you can leave the theater thinking to yourself, "I don't know what the hell just happened, but I understand why". Uncle Boonmee lumps everything together into a uniform greyness, deliberately, I think, and not unsuccessfully, but there's no sense of intuitive rightness with it the way there is, arguably, with the others. I would not call any of them "dreamlike"; that word fits Uncle Boonmee because parts of it feel, honestly, so arbitrarily cryptic, particularly the coda, after Boonmee dies,* and Tong and Jen react in each their own ways. The best moments of Uncle Boonmee have the impact of any great work of art, creating images and thoughts that carve themselves deep into your brain; but unlike Blissfully Yours and Syndromes especially, it's not hardly all best moments.

Apichatpong's aesthetic being what it is, it's hard to imagine any true believer in his work finding Uncle Boonmee a waste of time, any more than I can see it turning anyone who finds his work frustrating and lacking focus or meaning; but I think both sides of that debate can agree that it's a "less-so" iteration of his craft. It's perhaps a better of an entry point to his canon than his previous films, and that is both a good thing and bad, and for the same reason - it's easier to get a handle on the edges, more opaque in the middle, and not as radical in its ideas or its execution.

The film relates the final days of a plantation owner, Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar), dying of kidney failure. He is being visited by his sister-in-law, Jen (Jenjira Pongpas), and his nephew, Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee), wishing to bring him comfort in his last moments; but those aren't the only visitors. Death, it seems, attracts beings from the other world, and Boonmee also finds himself meeting up with the ghost of his wife, Huay (Natthakarn Aphaiwonk), and his long-lost soon Boonsong (Geerasak Kulhong), who many years ago chased a monkey ghost into the jungle, mated with her, and has now himself become a monkey ghost, with glowing red eyes and a pelt of jet black hair. For Boonmee, they are the memories of his past in this life; he's also receiving visions of what might be his lives before this one - though the film does not state that they must be - nor does it make it unmistakably clear that Boonmee, and not the audience, is the primary audience for these visions.

This might sound like a puzzle box movie, the kind which invites you to spend the next several days after you watch it figuring out what everything meant and how it all fits together. It might sound like that, but it most undoubtedly is not that. In keeping with Apichatpong's previous films, Uncle Boonmee always seems "about" the feeling and texture of individual scenes, and the overall laconic, even hypnotising mood of the whole experience, rather than about generating any particular "meaning", though I think that it's not hard to say, in the broad sense, that the film's themes are a fascination with the process of death (in a spiritual way, not a morbid one), and the regrets we have for our past. As much as he is obsessed with anything in particular, Boonmee is constantly preoccupied with karma: worried about punishment for the sins he committed in his youth as a soldier, curious about what he did in other lives that led, for good or ill, to this one. His dinner with his sister and nephew, and then with his ghostly wife and son as well (a scene that begins in a register of ineluctable creepiness and becomes quickly melancholic and surreal, once it becomes apparent that none of the three living people see any of this as peculiar in the slightest), the film's highest achievement, is primarily about nostalgia and remembrance, looking back and reflecting on all the steps between Then and Now.

In awarding the film its Cannes prize, jury president Tim Burton cited its creation of a dreamlike state, and as much of a cliché as the word "dreamy" is in describing any slow-moving art film with self-consciously anti-realistic elements, I've not been able to come up with a more apt description of Uncle Boonmee. Even more than Apichatpong's other films, which are equally slow-moving, meditative, and surreal, this plays like a somewhat disjointed series of hallucinations, right from its incredible opening sequence: several minutes of a cow being led through a jungle at night, bathed in shades of blue so dark it's nearly inscrutable, punctuated with a shot of a dark silhouette with glowing red eyes (a monkey ghost, we'll learn; but which monkey ghost? My first thought was that this figure might have been Boonmee in his past life, and the movie supports and does not support that reading to equal measure). Kind of the film to let us know in the opening minutes how it is to be watched: you have to give yourself over to the rhythms of the film completely, and not expect meaning to reveal itself except gradually, and invest yourself more in how each image, anchored by an omnipresent soundscape of natural noises, moves you. Perhaps that is what it's like to be near death, hyper-attuned to the small details of every moment; that is at any rate the feeling I got from Uncle Boonmee, that it encouraged an extremely reflective awareness of place and movement and color.

I did call this Apichatpong's "mainstream" film, didn't I? Yes, and only for this reason: compared to his earlier features, Blissfully Yours, Tropical Malady, and Syndromes and a Century, one does not get the same sense in Uncle Boonmee that the filmmaker is actively trying to destroy the medium of cinema and replace it with something more to his liking. For one thing, unlike the previous films, Uncle Boonmee does not break into two apparently irreconcilable parts; nor does it seriously challenge any particular aspect of film grammar, though viewers who find its beyond-glacial pace to be so much indulgent, pretentious fluff might not agree with me on that point exactly. In fact, compared to his previous work, it surprised me a little bit how easy it is to follow along what, specifically, happens in Uncle Boonmee: however inexplicable the import of any given event, it's never really confusing what events occur in what order.

Considering that, it's perhaps weird that, to me anyway, Uncle Boonmee ends up being the murkiest of Apichatpong's features. There's something about the contrast in emotions and sensations in each of the other three that adds up to an implicit whole, something you can leave the theater thinking to yourself, "I don't know what the hell just happened, but I understand why". Uncle Boonmee lumps everything together into a uniform greyness, deliberately, I think, and not unsuccessfully, but there's no sense of intuitive rightness with it the way there is, arguably, with the others. I would not call any of them "dreamlike"; that word fits Uncle Boonmee because parts of it feel, honestly, so arbitrarily cryptic, particularly the coda, after Boonmee dies,* and Tong and Jen react in each their own ways. The best moments of Uncle Boonmee have the impact of any great work of art, creating images and thoughts that carve themselves deep into your brain; but unlike Blissfully Yours and Syndromes especially, it's not hardly all best moments.

Apichatpong's aesthetic being what it is, it's hard to imagine any true believer in his work finding Uncle Boonmee a waste of time, any more than I can see it turning anyone who finds his work frustrating and lacking focus or meaning; but I think both sides of that debate can agree that it's a "less-so" iteration of his craft. It's perhaps a better of an entry point to his canon than his previous films, and that is both a good thing and bad, and for the same reason - it's easier to get a handle on the edges, more opaque in the middle, and not as radical in its ideas or its execution.