The ties that bind

The story of the McKerrow family is so ludicrously impossible that it could only possibly be true: no writer would dare string together this much contrived drama. In the mid-1960s, Loren and Carol McKerrow, having been told they could not conceived, adopted a baby boy, Marc - and no sooner had he come home than Carol ended up pregnant. She gave birth to another boy, Paul, and the following year to Todd. Growing up, Paul was the star of the family, the one who was good at sports and popular at school; Marc, already suffering from mood swings, did not handle this well.

Over the next couple of decades, Paul would discover that he was born the wrong gender, and has since become Kimberly Reed; while Marc suffered injuries that required a large chunk of his brain to be taken out. This left him at the mercy of violent outbursts that terrified those who loved him, and Kim and Marc had not seen each other for many years when she returned to Helena, Montana, for their 20-year high school reunion; hoping to reconnect with her brother, Kim was heartbroken to learn that he was unreachable. So far, we're right on the edge of what you could possibly get away with; but then, a month after the reunion, Marc's years-long quest to locate his birth parents bore fruit, and he discovered that he was the grandson of Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth. That Orson Welles, and that Rita Hayworth.

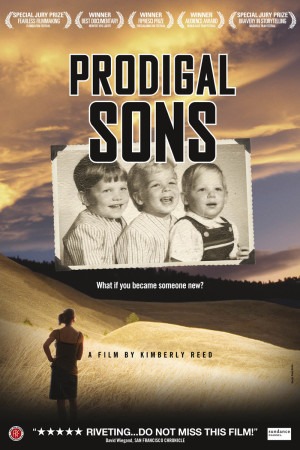

That kind of over-the-top family story would, at some point, have to be turned into a movie: but the 2008 documentary Prodigal Sons, which only received a proper commercial release in 2010,* is by no means an exploitative melodrama. In fact, it was directed by Kimberly Reed herself, resulting in one of the rawest and most exposed films that I think I have ever seen. It reminded me, above anything else, of another documentary that first premiered in 2008, Kurt Kuenne's Dear Zachary: like that film, Prodigal Sons tells an intensely personal story with equally intense openness, and the whole thing feels so intimate that I half feel like I have no business watching it. Yet, in both cases, I am profoundly grateful to the filmmakers for sharing their stories.

Before we get any further, it's important to make it clear what Prodigal Sons is not: it isn't a film about transgenderism, and it isn't a film about brain trauma and mental illness (at least, not primarily, although both of those things are irreducible elements of the greater story). It's about different ways of grappling with the past, with a version of oneself that no longer exists; and about the tensions that crop up in those families where there's just a little bit too much history for anyone to be at ease, ever. It is evident that Kim wants very badly to love Marc, but doesn't know how to do that, particularly since the one thing he most needs in life, to be surrounded by the reminders of his life before the accident, anchoring his present in a simpler if no happier past, is exactly the same thing that Kim needs least: constantly seeing images of Paul McKerrow, in all the photos Marc carries around like fetishes, serves only to remind her of the agony of being trapped beneath a thick wall of lies about her most essential self. This is the tension that underlies most of their interactions, and Kim's story, as presented within the film, is largely one of coming to terms with her own past as a means of reaching out to her brother in his hour of dire need (though she announces this in voiceover near the end, we've already been able to guess as much: given that Kim herself is responsible for including so much footage of Paul, we can safely assume that she no longer believes, as she states at one point, that she'd just as happily destroy any evidence that Paul ever existed).

If Kim's traumas largely animate the first half of Prodigal Sons, Marc's animate the second: his violent outbursts start to become an increasing problem not just for Kim, but for their mother, and for Marc's wife and daughter, all of whom are constantly in fear that he'll hurt himself or someone he loves. That word, "love", that's the tragedy: Marc is at all points shown to be a broken man, who genuinely believes every word he says about wanting to reconnect, wanting to be a happy member of a well-functioning family, and who knows even as he says these things that he's always a breath away from having what amounts to a fit of insanity. There has been a little bit of chatter as to whether Reed, in directing this film, is exploiting her brother, which is absurd. Prodigal Sons, among its many graces, is if anything a tribute to Marc's struggle to fight the thing inside him. Much of the latter part of the movie consists of conversations between Kim and Marc where it is unmistakably clear that she truly loves - make that, truly wants to love - her brother, and will do whatever is in her power to help him, to stay by his side. That's not exploitation, it's human tenderness at its most beautiful.

Reed never whitewashes any of this: she presents both herself and Marc with sentiment but without trying to hide the fact that they are both messy people, making the wrong decisions: she is remarkably unforgiving about her own desire for life to be exactly the way she demands, in defiance of the fact that none of us are ever given that luxury; nor does she soft-pedal the degree to which Marc is a legitimate danger, and that even before his brain injury, he was a resentful brother, jealous of a young sibling who, even as a woman, he seems to regard as the bigger man. There are moments where we, alongside Kim and the other family members, are watching Marc in his most stable moods, nervous as hell about how much longer until the next explosion; but like Kim, we're always hopeful that this time, maybe he's finally better.

Life will be what it is, though, and the despairing truth behind Prodigal Sons is that nothing gets resolved that quickly; the film ends without concluding anything, and armed with the knowledge that Marc died unexpectedly in June of 2010, it's even more sorrowful. The lesson of the film is that living is a process, not an end-point; Reed's perfect honesty and candor, for which all viewers must be forever thankful, documents a moment in a few very specific lives that anyone with a heart and mind can understand and recognise.

It's so beautiful and heartbreaking that I hesitate to point out the other way it reminded me of Dear Zachary: it has fairly significant problems as a cinematic object. I'm enough of a dick to mention that, but not enough of a dick to point particular things out (though I will mention Reed's use of voiceover narration to explain things we already know borders on the pathological), particularly since Reed has the excuse of not being a trained filmmaker, and that it seems that much of the early footage was shot without any real idea of the thing being cut into a documentary for an audience broader than the family. Still, it's not something that can be simply brushed away. It can, however, be forgiven in light of what the film does so altogether right: shine a light on some profoundly difficult lives with humility and generosity and love.

(A numerical ranking seems inordinately tactless)/10

Over the next couple of decades, Paul would discover that he was born the wrong gender, and has since become Kimberly Reed; while Marc suffered injuries that required a large chunk of his brain to be taken out. This left him at the mercy of violent outbursts that terrified those who loved him, and Kim and Marc had not seen each other for many years when she returned to Helena, Montana, for their 20-year high school reunion; hoping to reconnect with her brother, Kim was heartbroken to learn that he was unreachable. So far, we're right on the edge of what you could possibly get away with; but then, a month after the reunion, Marc's years-long quest to locate his birth parents bore fruit, and he discovered that he was the grandson of Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth. That Orson Welles, and that Rita Hayworth.

That kind of over-the-top family story would, at some point, have to be turned into a movie: but the 2008 documentary Prodigal Sons, which only received a proper commercial release in 2010,* is by no means an exploitative melodrama. In fact, it was directed by Kimberly Reed herself, resulting in one of the rawest and most exposed films that I think I have ever seen. It reminded me, above anything else, of another documentary that first premiered in 2008, Kurt Kuenne's Dear Zachary: like that film, Prodigal Sons tells an intensely personal story with equally intense openness, and the whole thing feels so intimate that I half feel like I have no business watching it. Yet, in both cases, I am profoundly grateful to the filmmakers for sharing their stories.

Before we get any further, it's important to make it clear what Prodigal Sons is not: it isn't a film about transgenderism, and it isn't a film about brain trauma and mental illness (at least, not primarily, although both of those things are irreducible elements of the greater story). It's about different ways of grappling with the past, with a version of oneself that no longer exists; and about the tensions that crop up in those families where there's just a little bit too much history for anyone to be at ease, ever. It is evident that Kim wants very badly to love Marc, but doesn't know how to do that, particularly since the one thing he most needs in life, to be surrounded by the reminders of his life before the accident, anchoring his present in a simpler if no happier past, is exactly the same thing that Kim needs least: constantly seeing images of Paul McKerrow, in all the photos Marc carries around like fetishes, serves only to remind her of the agony of being trapped beneath a thick wall of lies about her most essential self. This is the tension that underlies most of their interactions, and Kim's story, as presented within the film, is largely one of coming to terms with her own past as a means of reaching out to her brother in his hour of dire need (though she announces this in voiceover near the end, we've already been able to guess as much: given that Kim herself is responsible for including so much footage of Paul, we can safely assume that she no longer believes, as she states at one point, that she'd just as happily destroy any evidence that Paul ever existed).

If Kim's traumas largely animate the first half of Prodigal Sons, Marc's animate the second: his violent outbursts start to become an increasing problem not just for Kim, but for their mother, and for Marc's wife and daughter, all of whom are constantly in fear that he'll hurt himself or someone he loves. That word, "love", that's the tragedy: Marc is at all points shown to be a broken man, who genuinely believes every word he says about wanting to reconnect, wanting to be a happy member of a well-functioning family, and who knows even as he says these things that he's always a breath away from having what amounts to a fit of insanity. There has been a little bit of chatter as to whether Reed, in directing this film, is exploiting her brother, which is absurd. Prodigal Sons, among its many graces, is if anything a tribute to Marc's struggle to fight the thing inside him. Much of the latter part of the movie consists of conversations between Kim and Marc where it is unmistakably clear that she truly loves - make that, truly wants to love - her brother, and will do whatever is in her power to help him, to stay by his side. That's not exploitation, it's human tenderness at its most beautiful.

Reed never whitewashes any of this: she presents both herself and Marc with sentiment but without trying to hide the fact that they are both messy people, making the wrong decisions: she is remarkably unforgiving about her own desire for life to be exactly the way she demands, in defiance of the fact that none of us are ever given that luxury; nor does she soft-pedal the degree to which Marc is a legitimate danger, and that even before his brain injury, he was a resentful brother, jealous of a young sibling who, even as a woman, he seems to regard as the bigger man. There are moments where we, alongside Kim and the other family members, are watching Marc in his most stable moods, nervous as hell about how much longer until the next explosion; but like Kim, we're always hopeful that this time, maybe he's finally better.

Life will be what it is, though, and the despairing truth behind Prodigal Sons is that nothing gets resolved that quickly; the film ends without concluding anything, and armed with the knowledge that Marc died unexpectedly in June of 2010, it's even more sorrowful. The lesson of the film is that living is a process, not an end-point; Reed's perfect honesty and candor, for which all viewers must be forever thankful, documents a moment in a few very specific lives that anyone with a heart and mind can understand and recognise.

It's so beautiful and heartbreaking that I hesitate to point out the other way it reminded me of Dear Zachary: it has fairly significant problems as a cinematic object. I'm enough of a dick to mention that, but not enough of a dick to point particular things out (though I will mention Reed's use of voiceover narration to explain things we already know borders on the pathological), particularly since Reed has the excuse of not being a trained filmmaker, and that it seems that much of the early footage was shot without any real idea of the thing being cut into a documentary for an audience broader than the family. Still, it's not something that can be simply brushed away. It can, however, be forgiven in light of what the film does so altogether right: shine a light on some profoundly difficult lives with humility and generosity and love.

(A numerical ranking seems inordinately tactless)/10

Categories: documentaries, domestic dramas