The films of Studio Ghibli: If my father had been smart and really cool, and my mother had been gorgeous and a great cook, and our family had been rich, my whole life would've been different

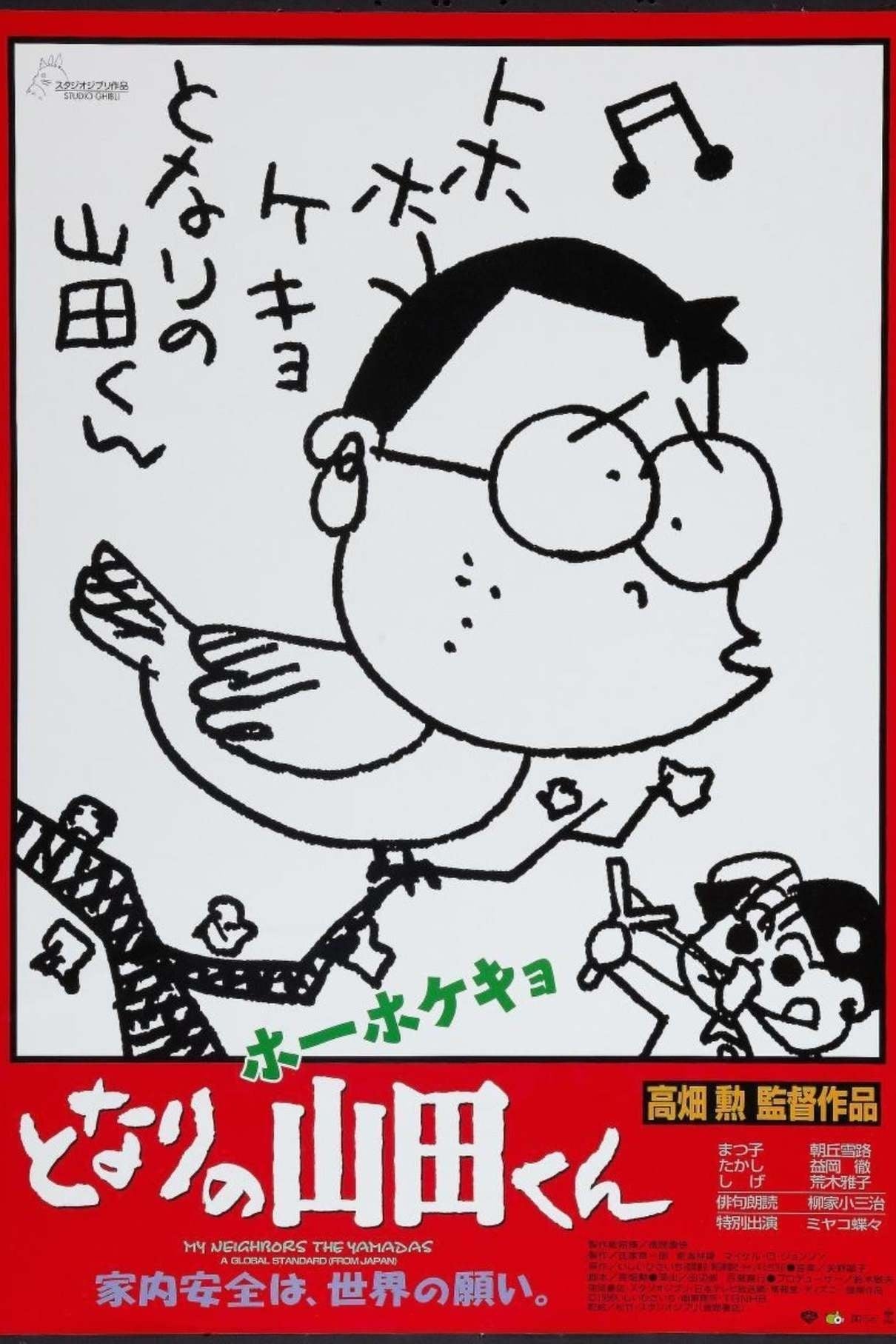

Takahata Isao's most recent feature to date, as of June 2010, My Neighbors the Yamadas opens with an image that is simultaneously simple and deeply significant: a child's pencil drawing, forming before our eyes.

There are two meanings to this opening shot, one ironic and the other quite serious. For there is, on the one hand, the fact that Yamadas boasts an extremely stylised hand-drawn look - the appearance of the film modeled upon Ishii Hisaichi's comic strip even as the plot is - that looks like literally no other animated feature I can name (though I haven't, of course, seen every animated feature), and certainly bears not the least resemblance to anything else that Studio Ghibli ever produced. It makes a certain kind of sense that the studio would want to show off its stunning new look by underscoring the very same hand-drawn, rough-sketched look that makes it so very distinctive.

There are two meanings to this opening shot, one ironic and the other quite serious. For there is, on the one hand, the fact that Yamadas boasts an extremely stylised hand-drawn look - the appearance of the film modeled upon Ishii Hisaichi's comic strip even as the plot is - that looks like literally no other animated feature I can name (though I haven't, of course, seen every animated feature), and certainly bears not the least resemblance to anything else that Studio Ghibli ever produced. It makes a certain kind of sense that the studio would want to show off its stunning new look by underscoring the very same hand-drawn, rough-sketched look that makes it so very distinctive.

And at the same time, not a blessed thing about Yamadas is actually handmade. It holds the distinction of being the first Ghibli feature painted entirely on computers, the logic being that it was easier to manipulate the very particular textural elements of the artwork in a computer than using practical materials. Indeed, it must be conceded even among we who love and adore hand-drawn animation (something Ghibli has never discarded with the scorn that American studios have; for example, 2008's Ponyo on the Cliff was hand-painted, for very little reason other than Miyazaki Hayao's desire that it should be), that Yamadas simply wouldn't work if done traditionally; the consistent, crippling flaw of cel animation is that the characters always look much smoother and "cartoony" than the backgrounds. This effect would have been fatal in Yamadas, where the point is very much that the art looks like a hand-penciled comic strip walking around and moving, and the characters and background needed to occupy the same plane, as it were.

All in a day's work for Takahata, who'd been experimenting with representational styles almost as long as he'd been directing for Ghibli: Only Yesterday, his second film with the company, pioneered two of the most important elements that would come back in Yamadas, namely the rigorously pastel color palette and the tendency to create scenes whose boundary was not the same as the film frame; three years after that, his Pom Poko was as much as anything a protracted experiment in how many different ways you could depict the same character within the space of a single movie. Still, neither of those features has a patch on Yamadas in the "crazy stylistic madness" race.

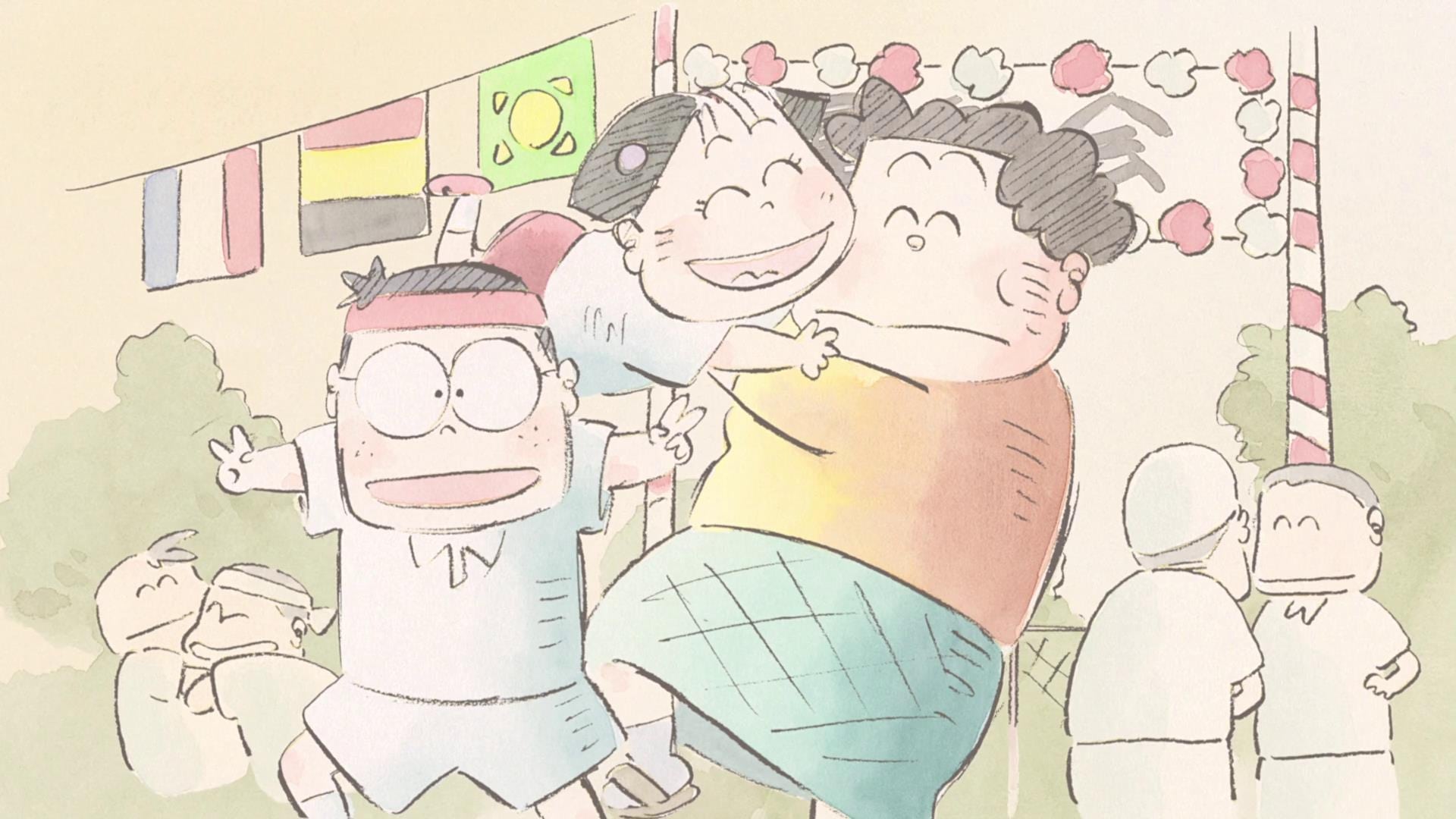

That image - a fairly typical one - expresses just about everything important about the movie's look: the dramatically washed-out colors, the sense that the characters and the backgrounds are drawn with charcoal or something like it, the rounded and wildly unrealistic design of the characters, the backgrounds that are sketched in only the fewest necessary lines to get the point of the space across. One of the things that is ever-fascinating in Yamadas is the way that the edge of the image is virtually never the edge of the mise en scène; not every shot I could have snipped shows it off so well, but there are endless examples in the film of a physical space that is defined by the edge of the draughtsman's pencil rather than the limit of the 1.85:1 frame.

That image - a fairly typical one - expresses just about everything important about the movie's look: the dramatically washed-out colors, the sense that the characters and the backgrounds are drawn with charcoal or something like it, the rounded and wildly unrealistic design of the characters, the backgrounds that are sketched in only the fewest necessary lines to get the point of the space across. One of the things that is ever-fascinating in Yamadas is the way that the edge of the image is virtually never the edge of the mise en scène; not every shot I could have snipped shows it off so well, but there are endless examples in the film of a physical space that is defined by the edge of the draughtsman's pencil rather than the limit of the 1.85:1 frame.

So what the hell is all this for? you might be asking right about now. For making me fall even more in love with Takahata Isao than I have been already, I might reply in my most surly voice, but it's a good point, and not readily answered: Yamadas, even by the standards of Stuidio Ghibli's frequently conflict-free narratives, really doesn't have anything like a plot. Following from that opening shot, the sun becomes a moon and the moon becomes the earth and the earth becomes Shige (Araki Masako), the grandmother of Nonoko (Uno Naomi), the little girl who was drawing and narrating all of this to us in the first place. These are the oldest and youngest members of the Yamada family, also including Shige's daughter Matsuko (Asaoka Yukiji), her husband Takashi (Masuoka Touru), and their elder child, teenage son Noboru (Isobata Hayato). And lastly, but by no means least, a taciturn dog who doesn't seem to care much about any of them, named Pochi.

You've already got pretty much all the story you're going to get, for Yamadas chases after its source material by being virtually nothing but a collection of vignettes, ranging from about ten minutes long to scarcely a few shots, in the lives of these not-outlandishly quirky people. Nonoko gets lost in a department store; Noboru receives his first phone call from a girl; Takashi and Matsuko constantly bicker over who has to do all of the petty chores that keep the Yamada household from descending into a filthy pit of anarchy. The bulk of the film is taken up with their low-grade battle, which not only doesn't bother their children, it seems clear that if they suddenly started openly loving each other, the family would be thrown fatally out of balance. Shige, meanwhile, plays the role of the vaguely unpleasant old woman who doesn't care who likes her opinion that is the right of all the elderly to adopt, and she plays it with aplomb.

You've already got pretty much all the story you're going to get, for Yamadas chases after its source material by being virtually nothing but a collection of vignettes, ranging from about ten minutes long to scarcely a few shots, in the lives of these not-outlandishly quirky people. Nonoko gets lost in a department store; Noboru receives his first phone call from a girl; Takashi and Matsuko constantly bicker over who has to do all of the petty chores that keep the Yamada household from descending into a filthy pit of anarchy. The bulk of the film is taken up with their low-grade battle, which not only doesn't bother their children, it seems clear that if they suddenly started openly loving each other, the family would be thrown fatally out of balance. Shige, meanwhile, plays the role of the vaguely unpleasant old woman who doesn't care who likes her opinion that is the right of all the elderly to adopt, and she plays it with aplomb.

That doesn't sound like much; and I suppose it isn't much, come to think about it. If it were laid out end to end, the film would probably look something like a sitcom, or worse yet a series of sketches: take these characters, plop them in this situation, watch the wackiness ensue. Sounds like hell, except that Takahata's immaculately perceptive script doesn't really play the way it sounds. Even when the situations in the movie are at their most contrived and unlikely (the bit about how everyone in the family starts to get forgetful after eating too much ginger jumps to mind), it's never in that strained way sometimes described by the invidious word "hijinks". For all that they are cartoons, according to a number of different definitions, the Yamadas never court buffoonery; one never feels that the filmmakers were playing towards the sort of grating "har har, ain't that just goofy?" humor typical of situational family comedy. In fact, it's surprisingly observational, based in the way that people honestly act and feel. The film is funny - at times very funny - but it's comedy based in human behavior, not writerly conceit. For myself, I was as engaged by the Yamadas as people more than as comic types, and by the end started to regard their crazy misadventures as the kind of marginally-exaggerated and misremembered stories that enthusiastic people will tell you, all in the most good-natured way, of course.

Out of all Ghibli's directors, Takahata is always the one who seems the most intensely focused on how human beings work I'd wager, so none of this ought to be surprising; and it certainly oughtn't be surprising that he ends the film with a big ol' group hug in which a karaoke version of "Que Sera, Sera" serves as the catalyst for the audience to realise that despite the sniping and absurdity that we've just watched for over an hour and a half, the Yamadas really do love and depend on each other. Okay, the karaoke part ought to be surprising, a little, but the way that the film ends by affirming that basically, people need each other, and that's great; that is vintage Takahata, and it leaves My Neighbors the Yamadas a much richer and moving film than you might guess from the idea of "wacky adventures of oddball people" mixed with that wildly excessive visual style.

Being a great director of animation, though, Takahata was of course not going to let his style interfere with the emotional density of his scenario; he used it instead to deepen the story that much more. The film essentially opens with someone's (Nonoko's?) very jumbled idea of how the Yamada family came to be - it involves a bobsled, rafting through a storm, and cutting children out of bamboo - and the visual leaps and flourishes on display here are a magnificent sight, with some imagery that simply couldn't have been achieved without the use of computers, and some that could have been, but is nonetheless dumbfoundingly beautiful in all its stylised glory.

This sequence is by far the most anxiously over-conceived in the feature; and it works incredibly well not just to introduce us to the off-kilter humor and beat-based storytelling style, but as a freewheeling metaphorical re-imagining of how family dynamics work. It bounds all over the place, as only animation could, and it's the best introduction to My Neighbors the Yamadas that I could imagine.

This sequence is by far the most anxiously over-conceived in the feature; and it works incredibly well not just to introduce us to the off-kilter humor and beat-based storytelling style, but as a freewheeling metaphorical re-imagining of how family dynamics work. It bounds all over the place, as only animation could, and it's the best introduction to My Neighbors the Yamadas that I could imagine.

That's a very specific example; for the most part, Takahata simply uses his very particular aesthetic in the service of creating an omnipresent good humor, presenting characters that we can't help but smile at, just for the appealing roundness and squishiness of their design (a lesson learned by animators back in the silent era and largely forgotten after Warners' closed up shop: characters that can be mushed about like a clay ball are just plain more delightful, and there's not a thing you can do to change that). It's hard not to respond to the impossible shapes that make up these characters and do so much to put forth their personalities, and this is true whether the character is involved in unabashed cartoon behavior-

-or just sitting there, looking way too adorable for words.

-or just sitting there, looking way too adorable for words.

Long story short, My Neighbors the Yamadas is an infinitely appealing comedy about the foibles of family, because both the situations it presents are identifiably real behind the exaggeration, and the comic strip minimalism of the world and characters has such a pleasantly clean, open feeling to it. This is an inordinately cheering movie to watch: teasing out the familiar and even happy elements found in family discord, and presenting such an ultimately gregarious, forgiving depiction of human bumbling, it's the kind of film that leaves you feeling awfully nice inside for having watched it. Or at least, it did for me. And that genuinely nice feeling is a precious rare thing to come by in a world full of cloying, "uplifting" dramedies. Therefore let me at the last sing praises to Takahata Isao, who lacks the international cachet of his illustrious partner Miyazaki Hayao, but whose work is of the greatest artistry and humanity, not just in the field of animation, but of cinema.

Long story short, My Neighbors the Yamadas is an infinitely appealing comedy about the foibles of family, because both the situations it presents are identifiably real behind the exaggeration, and the comic strip minimalism of the world and characters has such a pleasantly clean, open feeling to it. This is an inordinately cheering movie to watch: teasing out the familiar and even happy elements found in family discord, and presenting such an ultimately gregarious, forgiving depiction of human bumbling, it's the kind of film that leaves you feeling awfully nice inside for having watched it. Or at least, it did for me. And that genuinely nice feeling is a precious rare thing to come by in a world full of cloying, "uplifting" dramedies. Therefore let me at the last sing praises to Takahata Isao, who lacks the international cachet of his illustrious partner Miyazaki Hayao, but whose work is of the greatest artistry and humanity, not just in the field of animation, but of cinema.

There are two meanings to this opening shot, one ironic and the other quite serious. For there is, on the one hand, the fact that Yamadas boasts an extremely stylised hand-drawn look - the appearance of the film modeled upon Ishii Hisaichi's comic strip even as the plot is - that looks like literally no other animated feature I can name (though I haven't, of course, seen every animated feature), and certainly bears not the least resemblance to anything else that Studio Ghibli ever produced. It makes a certain kind of sense that the studio would want to show off its stunning new look by underscoring the very same hand-drawn, rough-sketched look that makes it so very distinctive.

There are two meanings to this opening shot, one ironic and the other quite serious. For there is, on the one hand, the fact that Yamadas boasts an extremely stylised hand-drawn look - the appearance of the film modeled upon Ishii Hisaichi's comic strip even as the plot is - that looks like literally no other animated feature I can name (though I haven't, of course, seen every animated feature), and certainly bears not the least resemblance to anything else that Studio Ghibli ever produced. It makes a certain kind of sense that the studio would want to show off its stunning new look by underscoring the very same hand-drawn, rough-sketched look that makes it so very distinctive.And at the same time, not a blessed thing about Yamadas is actually handmade. It holds the distinction of being the first Ghibli feature painted entirely on computers, the logic being that it was easier to manipulate the very particular textural elements of the artwork in a computer than using practical materials. Indeed, it must be conceded even among we who love and adore hand-drawn animation (something Ghibli has never discarded with the scorn that American studios have; for example, 2008's Ponyo on the Cliff was hand-painted, for very little reason other than Miyazaki Hayao's desire that it should be), that Yamadas simply wouldn't work if done traditionally; the consistent, crippling flaw of cel animation is that the characters always look much smoother and "cartoony" than the backgrounds. This effect would have been fatal in Yamadas, where the point is very much that the art looks like a hand-penciled comic strip walking around and moving, and the characters and background needed to occupy the same plane, as it were.

All in a day's work for Takahata, who'd been experimenting with representational styles almost as long as he'd been directing for Ghibli: Only Yesterday, his second film with the company, pioneered two of the most important elements that would come back in Yamadas, namely the rigorously pastel color palette and the tendency to create scenes whose boundary was not the same as the film frame; three years after that, his Pom Poko was as much as anything a protracted experiment in how many different ways you could depict the same character within the space of a single movie. Still, neither of those features has a patch on Yamadas in the "crazy stylistic madness" race.

That image - a fairly typical one - expresses just about everything important about the movie's look: the dramatically washed-out colors, the sense that the characters and the backgrounds are drawn with charcoal or something like it, the rounded and wildly unrealistic design of the characters, the backgrounds that are sketched in only the fewest necessary lines to get the point of the space across. One of the things that is ever-fascinating in Yamadas is the way that the edge of the image is virtually never the edge of the mise en scène; not every shot I could have snipped shows it off so well, but there are endless examples in the film of a physical space that is defined by the edge of the draughtsman's pencil rather than the limit of the 1.85:1 frame.

That image - a fairly typical one - expresses just about everything important about the movie's look: the dramatically washed-out colors, the sense that the characters and the backgrounds are drawn with charcoal or something like it, the rounded and wildly unrealistic design of the characters, the backgrounds that are sketched in only the fewest necessary lines to get the point of the space across. One of the things that is ever-fascinating in Yamadas is the way that the edge of the image is virtually never the edge of the mise en scène; not every shot I could have snipped shows it off so well, but there are endless examples in the film of a physical space that is defined by the edge of the draughtsman's pencil rather than the limit of the 1.85:1 frame.So what the hell is all this for? you might be asking right about now. For making me fall even more in love with Takahata Isao than I have been already, I might reply in my most surly voice, but it's a good point, and not readily answered: Yamadas, even by the standards of Stuidio Ghibli's frequently conflict-free narratives, really doesn't have anything like a plot. Following from that opening shot, the sun becomes a moon and the moon becomes the earth and the earth becomes Shige (Araki Masako), the grandmother of Nonoko (Uno Naomi), the little girl who was drawing and narrating all of this to us in the first place. These are the oldest and youngest members of the Yamada family, also including Shige's daughter Matsuko (Asaoka Yukiji), her husband Takashi (Masuoka Touru), and their elder child, teenage son Noboru (Isobata Hayato). And lastly, but by no means least, a taciturn dog who doesn't seem to care much about any of them, named Pochi.

You've already got pretty much all the story you're going to get, for Yamadas chases after its source material by being virtually nothing but a collection of vignettes, ranging from about ten minutes long to scarcely a few shots, in the lives of these not-outlandishly quirky people. Nonoko gets lost in a department store; Noboru receives his first phone call from a girl; Takashi and Matsuko constantly bicker over who has to do all of the petty chores that keep the Yamada household from descending into a filthy pit of anarchy. The bulk of the film is taken up with their low-grade battle, which not only doesn't bother their children, it seems clear that if they suddenly started openly loving each other, the family would be thrown fatally out of balance. Shige, meanwhile, plays the role of the vaguely unpleasant old woman who doesn't care who likes her opinion that is the right of all the elderly to adopt, and she plays it with aplomb.

You've already got pretty much all the story you're going to get, for Yamadas chases after its source material by being virtually nothing but a collection of vignettes, ranging from about ten minutes long to scarcely a few shots, in the lives of these not-outlandishly quirky people. Nonoko gets lost in a department store; Noboru receives his first phone call from a girl; Takashi and Matsuko constantly bicker over who has to do all of the petty chores that keep the Yamada household from descending into a filthy pit of anarchy. The bulk of the film is taken up with their low-grade battle, which not only doesn't bother their children, it seems clear that if they suddenly started openly loving each other, the family would be thrown fatally out of balance. Shige, meanwhile, plays the role of the vaguely unpleasant old woman who doesn't care who likes her opinion that is the right of all the elderly to adopt, and she plays it with aplomb.That doesn't sound like much; and I suppose it isn't much, come to think about it. If it were laid out end to end, the film would probably look something like a sitcom, or worse yet a series of sketches: take these characters, plop them in this situation, watch the wackiness ensue. Sounds like hell, except that Takahata's immaculately perceptive script doesn't really play the way it sounds. Even when the situations in the movie are at their most contrived and unlikely (the bit about how everyone in the family starts to get forgetful after eating too much ginger jumps to mind), it's never in that strained way sometimes described by the invidious word "hijinks". For all that they are cartoons, according to a number of different definitions, the Yamadas never court buffoonery; one never feels that the filmmakers were playing towards the sort of grating "har har, ain't that just goofy?" humor typical of situational family comedy. In fact, it's surprisingly observational, based in the way that people honestly act and feel. The film is funny - at times very funny - but it's comedy based in human behavior, not writerly conceit. For myself, I was as engaged by the Yamadas as people more than as comic types, and by the end started to regard their crazy misadventures as the kind of marginally-exaggerated and misremembered stories that enthusiastic people will tell you, all in the most good-natured way, of course.

Out of all Ghibli's directors, Takahata is always the one who seems the most intensely focused on how human beings work I'd wager, so none of this ought to be surprising; and it certainly oughtn't be surprising that he ends the film with a big ol' group hug in which a karaoke version of "Que Sera, Sera" serves as the catalyst for the audience to realise that despite the sniping and absurdity that we've just watched for over an hour and a half, the Yamadas really do love and depend on each other. Okay, the karaoke part ought to be surprising, a little, but the way that the film ends by affirming that basically, people need each other, and that's great; that is vintage Takahata, and it leaves My Neighbors the Yamadas a much richer and moving film than you might guess from the idea of "wacky adventures of oddball people" mixed with that wildly excessive visual style.

Being a great director of animation, though, Takahata was of course not going to let his style interfere with the emotional density of his scenario; he used it instead to deepen the story that much more. The film essentially opens with someone's (Nonoko's?) very jumbled idea of how the Yamada family came to be - it involves a bobsled, rafting through a storm, and cutting children out of bamboo - and the visual leaps and flourishes on display here are a magnificent sight, with some imagery that simply couldn't have been achieved without the use of computers, and some that could have been, but is nonetheless dumbfoundingly beautiful in all its stylised glory.

This sequence is by far the most anxiously over-conceived in the feature; and it works incredibly well not just to introduce us to the off-kilter humor and beat-based storytelling style, but as a freewheeling metaphorical re-imagining of how family dynamics work. It bounds all over the place, as only animation could, and it's the best introduction to My Neighbors the Yamadas that I could imagine.

This sequence is by far the most anxiously over-conceived in the feature; and it works incredibly well not just to introduce us to the off-kilter humor and beat-based storytelling style, but as a freewheeling metaphorical re-imagining of how family dynamics work. It bounds all over the place, as only animation could, and it's the best introduction to My Neighbors the Yamadas that I could imagine.That's a very specific example; for the most part, Takahata simply uses his very particular aesthetic in the service of creating an omnipresent good humor, presenting characters that we can't help but smile at, just for the appealing roundness and squishiness of their design (a lesson learned by animators back in the silent era and largely forgotten after Warners' closed up shop: characters that can be mushed about like a clay ball are just plain more delightful, and there's not a thing you can do to change that). It's hard not to respond to the impossible shapes that make up these characters and do so much to put forth their personalities, and this is true whether the character is involved in unabashed cartoon behavior-

-or just sitting there, looking way too adorable for words.

-or just sitting there, looking way too adorable for words. Long story short, My Neighbors the Yamadas is an infinitely appealing comedy about the foibles of family, because both the situations it presents are identifiably real behind the exaggeration, and the comic strip minimalism of the world and characters has such a pleasantly clean, open feeling to it. This is an inordinately cheering movie to watch: teasing out the familiar and even happy elements found in family discord, and presenting such an ultimately gregarious, forgiving depiction of human bumbling, it's the kind of film that leaves you feeling awfully nice inside for having watched it. Or at least, it did for me. And that genuinely nice feeling is a precious rare thing to come by in a world full of cloying, "uplifting" dramedies. Therefore let me at the last sing praises to Takahata Isao, who lacks the international cachet of his illustrious partner Miyazaki Hayao, but whose work is of the greatest artistry and humanity, not just in the field of animation, but of cinema.

Long story short, My Neighbors the Yamadas is an infinitely appealing comedy about the foibles of family, because both the situations it presents are identifiably real behind the exaggeration, and the comic strip minimalism of the world and characters has such a pleasantly clean, open feeling to it. This is an inordinately cheering movie to watch: teasing out the familiar and even happy elements found in family discord, and presenting such an ultimately gregarious, forgiving depiction of human bumbling, it's the kind of film that leaves you feeling awfully nice inside for having watched it. Or at least, it did for me. And that genuinely nice feeling is a precious rare thing to come by in a world full of cloying, "uplifting" dramedies. Therefore let me at the last sing praises to Takahata Isao, who lacks the international cachet of his illustrious partner Miyazaki Hayao, but whose work is of the greatest artistry and humanity, not just in the field of animation, but of cinema.

Categories: animation, comedies, japanese cinema, studio ghibli, takahata isao, warm fuzzies