The films of Studio Ghibli: Misty water-colored memories

"I didn't intend for the ten-year-old me to come along on this trip", muses 27-year-old Taeko (Imai Miki) early in Only Yesterday, the fifth feature produced by Studio Ghibli. And yet the fifth-grade incarnation of Taeko (Honna Youko) is a constant companion in her older self's inner life throughout the ten-day vacation in the Yamagata countryside that forms the functional equivalent to a plot structure in this, the second film directed by Takahata Isao for that company.

The reason for this oppressive nostalgia is easy enough to explain: Taeko is traveling to the country to help harvest safflowers for dye, staying with her sister's in-laws, and in so doing fulfilling a desire that she was never able to experience in childhood, to visit out-of-town relatives like all of her friends did over school holidays. So it is that the first of what will prove to be many flashbacks is to the young Taeko pestering her parents about why, exactly, they can't go to Grandma's country estate. Because Grandma lives with us in Tokyo, is the measured reply.

No matter what your preconceptions about anime might be, Only Yesterday probably confounds them. Even by the standards of "serious" Japanese animation, it is a remarkably un-fantastic story about a youngish woman wrapped up in troubling thoughts to the point of morbidity; fully the first half consists of virtually nothing but disjointed, episodic memories of a single year in grade school, which formed the entirety of the manga from which Takahata spun his uncommonly rich consideration of the relationship between childhood memories and adult worries (the title more literally translates as Memories Come Tumbling Down, but I for one rather like the English version). Even once the actual plot kicks into high gear, you'd never ever believe me if I told you that it fills 118 minutes, a running time that speeds by with abandon. A twentysomething woman finds that the simple life suits her well, and she sort of becomes infatuated with a young man she finds in the country. And that's all she wrote.

It is the most singularly mature, adult-oriented of all Ghibli's theatrical features; thankfully, it was released in a country where mature animation isn't a wild oxymoron, and it ended up being a respectable box-office success. Whether it led to an explosion of anime projects about introspective young adults, I cannot say; but as itself, a single and miraculous object that isn't quite like anything else I've seen, from Japan, America, or anywhere else... well, I suppose I've tipped my hand with the word "miraculous", as to what I think about the movie.

Takahata, I presume, was never a young woman, and it's difficult to imagine how he was thus able to bring such an overwhelming feeling of close observation and burning emotional realism to the project. The manga was something of an autobiography for Okamoto Hotaru, and that probably explains a little bit of it; but the manga also didn't cover one moment of Taeko's adult life, and it is this framing narrative that pushes Only Yesterday from "appealing, precisely-detailed study of the life of a child in Tokyo in 1966" to "profoundly moving and truthful story of human experience that I want to wrap around myself like a fleece blanket". Taeko, narrating from an indistinct point after the events of her vacation, ceases to feel within moments like a cartoon character; by the end of the film, she no longer feels even like a live-action movie character. The calm but obviously emotionally-heightened way in which she recalls the events of 1966 and 1982 takes on the character of listening to a real person sitting back and recollecting her life; this realism is only increased by the sometimes documentary-esque degree to which Takahata depicts the reality of safflower farming, or watching the hugely popular TV show Hyokkori hyotan-jima (seemingly like Howdy Doody, but not filled with the black soul of pure evil).

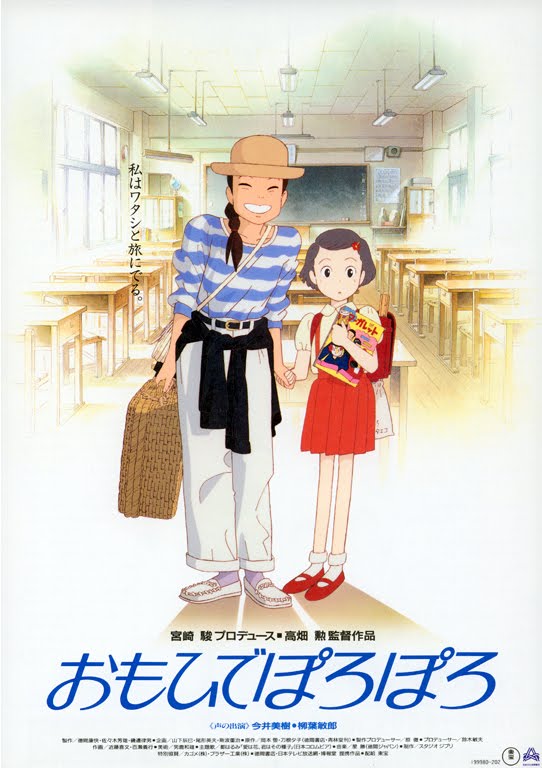

What's truly strange is that this effect is present even though grown-up Taeko is designed with a roundness of line and brightness of color - and anime's characteristic saucer eyes - that makes her unmistakably a "cartoon", especially compared to the rigorous physical realism of Takahata's previous feature, Grave of the Fireflies.

That's hardly a realistic image, and yet the woman depicted is just about as realistic as any animated figure ever has been.

That's hardly a realistic image, and yet the woman depicted is just about as realistic as any animated figure ever has been.

Look again, though. See those lines on her face? Those are muscle lines. You know what you pretty much never see in anime?

In a bid for increased realism, to that we'd be more instantly attracted to the character, I presume, Takahata did something very rarely done in his industry: the audio in the adult half of Only Yesterday was recorded before the animated was done, so that the movements of characters' faces could line up with their speech as closely as possible. Sounds like a small thing, but the effect is uncanny, especially since the "young" half was done much more according to the normal procedure: animation, then the lines were recorded to match the duration of the time that characters moved their mouths.

The visual distinction between 27-year-old Taeko and her memories is more pronounced than that, though. Not only are the 1966 scenes still more "cartoony" than the 1982 scenes, they're colored with a much softer pastel palette, that evokes the haze of distant memories like nobody's business. When the film cuts from one time period to another, it's jarring but it makes absolute intuitive sense. These frames do not appear next to each other in the film, but they wonderfully express what I'm talking about:

It feels almost like they're not from the same film; but they are. And that dichotomy serves only to deepen the emotional richness of the film's story. Next time somebody tells you that there's no reason a character study about a woman recalling her childhood traumas can't utterly justify itself as animation (I am certain this happens to you regularly), just sit that person in front of Only Yesterday and think about what you'll demand as proof of their apology.

It feels almost like they're not from the same film; but they are. And that dichotomy serves only to deepen the emotional richness of the film's story. Next time somebody tells you that there's no reason a character study about a woman recalling her childhood traumas can't utterly justify itself as animation (I am certain this happens to you regularly), just sit that person in front of Only Yesterday and think about what you'll demand as proof of their apology.

Having already made the 1966 scenes more childlike and cartoony, Takahata went all the way, so to speak, indulging in no end of tiny formal flourishes such as the free blending of Taeka's thoughts with the aforementioned puppet show, resulting in a weird but charming abbreviated musical number; or presenting her feelings in an Expressionist way, particularly in the sequence involving her first crush. The limited detail of the 1966 aesthetic even turns out to be a boon: in some wide shots, Taeka barely seems to have a face, and this is never just an example of cheap production value, but a stunning way to present character with admirable visual efficiency. For example, just before this shot, Taeka overhears her mother calling her "not normal".

There's another thing that happens throughout the 1966 scenes - you can just barely see it in that last image - that carries the minimalism of that timeline's aesthetic to an exciting extreme. Very often, the backgrounds seem to recede into mist, or just plain nothingness. While the backgrounds of the 1982 story are rich and detailed and "deep", many of the backgrounds in 1966 seem paper-thin, almost exactly like picture book illustrations.

There's another thing that happens throughout the 1966 scenes - you can just barely see it in that last image - that carries the minimalism of that timeline's aesthetic to an exciting extreme. Very often, the backgrounds seem to recede into mist, or just plain nothingness. While the backgrounds of the 1982 story are rich and detailed and "deep", many of the backgrounds in 1966 seem paper-thin, almost exactly like picture book illustrations.

All told, Only Yesterday is a haunting masterpiece, dramatising the act of remembering with the most remarkable grace and subtlety; at times indulging in sheer, unmitigated poetry, as in a sequence that depicts with scientific fascination the process of harvesting safflowers, as a perfectly beautiful chorale plays on the soundtrack (the use of music, throughout, is exemplary, and worth an essay all its own; I will hear content myself with proclaiming composer Hoshi Katsu a proper genius, and lamenting that he's apparently been retired for a decade and a half), and the flowers themselves are depicted with the most loving detail.

All told, Only Yesterday is a haunting masterpiece, dramatising the act of remembering with the most remarkable grace and subtlety; at times indulging in sheer, unmitigated poetry, as in a sequence that depicts with scientific fascination the process of harvesting safflowers, as a perfectly beautiful chorale plays on the soundtrack (the use of music, throughout, is exemplary, and worth an essay all its own; I will hear content myself with proclaiming composer Hoshi Katsu a proper genius, and lamenting that he's apparently been retired for a decade and a half), and the flowers themselves are depicted with the most loving detail.

Only Yesterday is the kind of motion picture that makes you feel more alive, more human, just for having watched it; in that respect it is a fine successor to Grave of the Fireflies, though it is nowhere near as heartbreaking (Taeko's remembrance of the pains of her youth is touching, true, but she clearly understands that without that pain she would not be as she is, and thus, we understand it too). Its primary merit, perhaps, is that it presents us with a fine example of human feeling, and this is a rather modest goal for a work of art to set itself to pursuing. But on the other hand, it's the only truly worthy goal that art can aspire to.

Only Yesterday is the kind of motion picture that makes you feel more alive, more human, just for having watched it; in that respect it is a fine successor to Grave of the Fireflies, though it is nowhere near as heartbreaking (Taeko's remembrance of the pains of her youth is touching, true, but she clearly understands that without that pain she would not be as she is, and thus, we understand it too). Its primary merit, perhaps, is that it presents us with a fine example of human feeling, and this is a rather modest goal for a work of art to set itself to pursuing. But on the other hand, it's the only truly worthy goal that art can aspire to.

So, here's the sick joke: Only Yesterday, a cinematic masterpiece of the first order, can't be watched on DVD by people in my beloved United States (it's readily available everywhere else, though, if I am not mistaken), because the Walt Disney Company, gatekeepers of all things Ghibli in the West, isn't comfortable releasing an animated film with a major plot sequence hinging on fifth-grade girls fascinated and terrified by their first periods. Because menstruation, don't forget, is a filthy and horrid thing that has no place in a story of a woman who was once a girl. Ah, well, I found it without too much trouble, and for the love of all things beautiful in the world, I hope everyone else will try to do the same.

The reason for this oppressive nostalgia is easy enough to explain: Taeko is traveling to the country to help harvest safflowers for dye, staying with her sister's in-laws, and in so doing fulfilling a desire that she was never able to experience in childhood, to visit out-of-town relatives like all of her friends did over school holidays. So it is that the first of what will prove to be many flashbacks is to the young Taeko pestering her parents about why, exactly, they can't go to Grandma's country estate. Because Grandma lives with us in Tokyo, is the measured reply.

No matter what your preconceptions about anime might be, Only Yesterday probably confounds them. Even by the standards of "serious" Japanese animation, it is a remarkably un-fantastic story about a youngish woman wrapped up in troubling thoughts to the point of morbidity; fully the first half consists of virtually nothing but disjointed, episodic memories of a single year in grade school, which formed the entirety of the manga from which Takahata spun his uncommonly rich consideration of the relationship between childhood memories and adult worries (the title more literally translates as Memories Come Tumbling Down, but I for one rather like the English version). Even once the actual plot kicks into high gear, you'd never ever believe me if I told you that it fills 118 minutes, a running time that speeds by with abandon. A twentysomething woman finds that the simple life suits her well, and she sort of becomes infatuated with a young man she finds in the country. And that's all she wrote.

It is the most singularly mature, adult-oriented of all Ghibli's theatrical features; thankfully, it was released in a country where mature animation isn't a wild oxymoron, and it ended up being a respectable box-office success. Whether it led to an explosion of anime projects about introspective young adults, I cannot say; but as itself, a single and miraculous object that isn't quite like anything else I've seen, from Japan, America, or anywhere else... well, I suppose I've tipped my hand with the word "miraculous", as to what I think about the movie.

Takahata, I presume, was never a young woman, and it's difficult to imagine how he was thus able to bring such an overwhelming feeling of close observation and burning emotional realism to the project. The manga was something of an autobiography for Okamoto Hotaru, and that probably explains a little bit of it; but the manga also didn't cover one moment of Taeko's adult life, and it is this framing narrative that pushes Only Yesterday from "appealing, precisely-detailed study of the life of a child in Tokyo in 1966" to "profoundly moving and truthful story of human experience that I want to wrap around myself like a fleece blanket". Taeko, narrating from an indistinct point after the events of her vacation, ceases to feel within moments like a cartoon character; by the end of the film, she no longer feels even like a live-action movie character. The calm but obviously emotionally-heightened way in which she recalls the events of 1966 and 1982 takes on the character of listening to a real person sitting back and recollecting her life; this realism is only increased by the sometimes documentary-esque degree to which Takahata depicts the reality of safflower farming, or watching the hugely popular TV show Hyokkori hyotan-jima (seemingly like Howdy Doody, but not filled with the black soul of pure evil).

What's truly strange is that this effect is present even though grown-up Taeko is designed with a roundness of line and brightness of color - and anime's characteristic saucer eyes - that makes her unmistakably a "cartoon", especially compared to the rigorous physical realism of Takahata's previous feature, Grave of the Fireflies.

That's hardly a realistic image, and yet the woman depicted is just about as realistic as any animated figure ever has been.

That's hardly a realistic image, and yet the woman depicted is just about as realistic as any animated figure ever has been.Look again, though. See those lines on her face? Those are muscle lines. You know what you pretty much never see in anime?

In a bid for increased realism, to that we'd be more instantly attracted to the character, I presume, Takahata did something very rarely done in his industry: the audio in the adult half of Only Yesterday was recorded before the animated was done, so that the movements of characters' faces could line up with their speech as closely as possible. Sounds like a small thing, but the effect is uncanny, especially since the "young" half was done much more according to the normal procedure: animation, then the lines were recorded to match the duration of the time that characters moved their mouths.

The visual distinction between 27-year-old Taeko and her memories is more pronounced than that, though. Not only are the 1966 scenes still more "cartoony" than the 1982 scenes, they're colored with a much softer pastel palette, that evokes the haze of distant memories like nobody's business. When the film cuts from one time period to another, it's jarring but it makes absolute intuitive sense. These frames do not appear next to each other in the film, but they wonderfully express what I'm talking about:

It feels almost like they're not from the same film; but they are. And that dichotomy serves only to deepen the emotional richness of the film's story. Next time somebody tells you that there's no reason a character study about a woman recalling her childhood traumas can't utterly justify itself as animation (I am certain this happens to you regularly), just sit that person in front of Only Yesterday and think about what you'll demand as proof of their apology.

It feels almost like they're not from the same film; but they are. And that dichotomy serves only to deepen the emotional richness of the film's story. Next time somebody tells you that there's no reason a character study about a woman recalling her childhood traumas can't utterly justify itself as animation (I am certain this happens to you regularly), just sit that person in front of Only Yesterday and think about what you'll demand as proof of their apology.Having already made the 1966 scenes more childlike and cartoony, Takahata went all the way, so to speak, indulging in no end of tiny formal flourishes such as the free blending of Taeka's thoughts with the aforementioned puppet show, resulting in a weird but charming abbreviated musical number; or presenting her feelings in an Expressionist way, particularly in the sequence involving her first crush. The limited detail of the 1966 aesthetic even turns out to be a boon: in some wide shots, Taeka barely seems to have a face, and this is never just an example of cheap production value, but a stunning way to present character with admirable visual efficiency. For example, just before this shot, Taeka overhears her mother calling her "not normal".

There's another thing that happens throughout the 1966 scenes - you can just barely see it in that last image - that carries the minimalism of that timeline's aesthetic to an exciting extreme. Very often, the backgrounds seem to recede into mist, or just plain nothingness. While the backgrounds of the 1982 story are rich and detailed and "deep", many of the backgrounds in 1966 seem paper-thin, almost exactly like picture book illustrations.

There's another thing that happens throughout the 1966 scenes - you can just barely see it in that last image - that carries the minimalism of that timeline's aesthetic to an exciting extreme. Very often, the backgrounds seem to recede into mist, or just plain nothingness. While the backgrounds of the 1982 story are rich and detailed and "deep", many of the backgrounds in 1966 seem paper-thin, almost exactly like picture book illustrations. All told, Only Yesterday is a haunting masterpiece, dramatising the act of remembering with the most remarkable grace and subtlety; at times indulging in sheer, unmitigated poetry, as in a sequence that depicts with scientific fascination the process of harvesting safflowers, as a perfectly beautiful chorale plays on the soundtrack (the use of music, throughout, is exemplary, and worth an essay all its own; I will hear content myself with proclaiming composer Hoshi Katsu a proper genius, and lamenting that he's apparently been retired for a decade and a half), and the flowers themselves are depicted with the most loving detail.

All told, Only Yesterday is a haunting masterpiece, dramatising the act of remembering with the most remarkable grace and subtlety; at times indulging in sheer, unmitigated poetry, as in a sequence that depicts with scientific fascination the process of harvesting safflowers, as a perfectly beautiful chorale plays on the soundtrack (the use of music, throughout, is exemplary, and worth an essay all its own; I will hear content myself with proclaiming composer Hoshi Katsu a proper genius, and lamenting that he's apparently been retired for a decade and a half), and the flowers themselves are depicted with the most loving detail. Only Yesterday is the kind of motion picture that makes you feel more alive, more human, just for having watched it; in that respect it is a fine successor to Grave of the Fireflies, though it is nowhere near as heartbreaking (Taeko's remembrance of the pains of her youth is touching, true, but she clearly understands that without that pain she would not be as she is, and thus, we understand it too). Its primary merit, perhaps, is that it presents us with a fine example of human feeling, and this is a rather modest goal for a work of art to set itself to pursuing. But on the other hand, it's the only truly worthy goal that art can aspire to.

Only Yesterday is the kind of motion picture that makes you feel more alive, more human, just for having watched it; in that respect it is a fine successor to Grave of the Fireflies, though it is nowhere near as heartbreaking (Taeko's remembrance of the pains of her youth is touching, true, but she clearly understands that without that pain she would not be as she is, and thus, we understand it too). Its primary merit, perhaps, is that it presents us with a fine example of human feeling, and this is a rather modest goal for a work of art to set itself to pursuing. But on the other hand, it's the only truly worthy goal that art can aspire to.So, here's the sick joke: Only Yesterday, a cinematic masterpiece of the first order, can't be watched on DVD by people in my beloved United States (it's readily available everywhere else, though, if I am not mistaken), because the Walt Disney Company, gatekeepers of all things Ghibli in the West, isn't comfortable releasing an animated film with a major plot sequence hinging on fifth-grade girls fascinated and terrified by their first periods. Because menstruation, don't forget, is a filthy and horrid thing that has no place in a story of a woman who was once a girl. Ah, well, I found it without too much trouble, and for the love of all things beautiful in the world, I hope everyone else will try to do the same.