Circumstances and consquences

In 2004, a 23-year-old French woman named Marie-Leonie Leblanc reported that she had been attacked by North African immigrants who hurled anti-Semitic slurs at her. That Leblanc was not Jewish was merely the first head-scratching moment in a narrative that quickly unraveled in the span of a month, when it was found that she had completely fabricated the evidence of the assault; this proved just enough time for it to become an international incident (Ariel Sharon was obliged to speak words of caution to France's Jewish community before all was said and done).

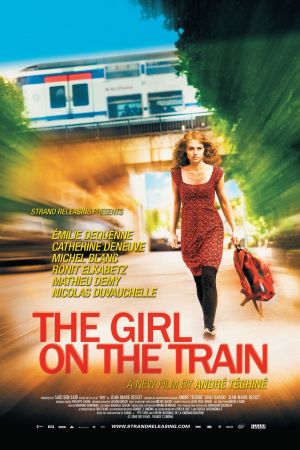

One year later, the playwright Jean-Marie Bessett fictionalised this event in his play RER (the Réseau Express Régional is a train system servicing Paris and its suburbs, and it was on a RER train that Leblanc claimed to have been attacked); and in 2009, the great director André Téchiné turned that play into a film, The Girl on the Train (or, if you prefer the more evocative French title, The Girl from the RER), which is presently crawling its way across U.S. art theaters, where it is enjoying the fixed attention of dozens, if not scores, of viewers.

It's probably just as well: Téchiné is not the world's easiest filmmaker, and The Girl on the Train is a particularly gnarly knot of a movie: focusing its entire attention on one outrageous, unsupportable lie - the moment that the protagonist, Jeanne (Émilie Dequenne), announces that she's been "attacked", the movie itself breaks into two parts - and making no real effort to explain what the hell is going on in the mind of the liar. Do we walk out of the theater making conjectures about what made Jeanne do this thing, one in a string of unfathomable choices she makes over the course of the plot? Yes, undoubtedly. And my conjectures aren't likely to be the same as your conjectures. The film is in some ways a tabula rasa that permits the viewer to reflect at his or her leisure, but it is not a puzzle with a solution. Just for fun, check out the film's Metacritic page: at this writing, you can find two consecutive pullquotes declaring that it's "really about... people. Just regular people" and "What the film is really about is social embarrassment".

What it's really about is Jeanne, her mother Louise (Catherine Deneuve, whom convention requires me to refer to as "the great Catherine Deneuve"), her unsavory temporary boyfriend Franck (Nicolas Duvauchelle), and the Bleistein family: Samuel (Michel Blanc), a famous lawyer and old friend of Louise's, his son Alex (Mathieu Demy), his daughter-in-law Judith (Ronit Elkabetz), and in some ways most importantly, his grandson Nathan (Jérémy Quaegebeur), preparing for his bar mitzvah. There are both superficial and probing ways that the two main lines of the plot - Jeanne and her mother vs. Nathan and his parents - mirror and/or contrast each other; there is the coolness between Jeanne and Louise that sometimes pierces (a recurrent image of Louise playing with the young children she's watching while Jeanne watches from a distance is, I think, the closest we come to an explanation for what happened), while Nathan's feelings towards Alex are nearly as icy; but the Bleisteins, unlike their gentile counterparts, also have a messy kind of personal intimacy that doesn't curdle, though it still causes problems for them. I should rather let the individual viewer tease out these sorts of connections, though, since in a very real sense watching The Girl on the Train is a matter of witnessing these connections organically rise up from the scenario.

As the plot slides, on, with Louise inducing Samuel to take up Jeanne's case although both of them believe more or less that she's lying, the film's questions become thicker and more confusing, leading the story into corners that never find any sort of traditionally satisfying resolution. The film does not want to part with its meaning readily, and in a certain sense, this is a strike against it: there comes a point where opacity shades into smug pretension, although the details we observe of the characters, and even more the performances giving the characters life (Dequenne is particularly transfixing, all the more since she has by far the most veiled role to play), leave the film with enough of a beating human heart that I can't really fathom how anyone could honestly accuse it of being pretentious. Still, it's an experience that is more valuable for the challenge it poses to the audience than the statements it makes. That's not really a fun night out at the movies, any way you slice it.

A master craftsman, Téchiné does what he can to make the experience a smooth one through the incredibly judicious use of camera angles, and even more so with a peculiar but wildly effective editing trick that pops up over and over again: the film cuts from one shot of a character to another shot, very similarly if not identically framed, in the same location - it looks, at first, like the film has a stutter. It keeps the audience from getting properly situated, and suggests a fragmentary reality in keeping with the script's refusal to give us answers: who can say what's "true" about a situation that won't even hold still and have the decency not to keep jump-cutting? Less cutely: the editing rather unmistakably violates the film's realism, which in turn devalues that realism, which in turn devalues the explanation for the film's reality.

Characteristically, Téchiné also uses some great musical cues, along with an excellent original score by Philippe Sarde; there are several moments in the film, beginning with its masterful opening shot (the POV of a train barreling through a subway tunnel, with the exit just a tiny dot in the far distance, as lights rush past) set to a peculiar, militaristic bagpipe piece, on to the moody use of Bob Dylan's "Lay Lady Lay" to accompany a pantomime montage revealing how disconnected Jeanne feels from the rest of the world - itself a repeated motif, especially in the first half, and it's not probably that two of the film's best scenes consist of Jeanne listening to music through headphones and ignoring the world around her - there's always a deep, intuitive rightness to the music, the kind that makes sense almost despite your attempt to consciously figure out why.

I suppose there are people who will be frustrated with the film's slow pace (it is a very long 105 minutes) and its practiced ambiguity, but The Girl on the Train is a character study par excellence, that simmers and lingers and reveals itself only by inches. The demands it makes upon its audience are not tiny, but its rewards are very considerable: it allows us to ponder how human beings think, without asking that we be judgmental or reductive.

One year later, the playwright Jean-Marie Bessett fictionalised this event in his play RER (the Réseau Express Régional is a train system servicing Paris and its suburbs, and it was on a RER train that Leblanc claimed to have been attacked); and in 2009, the great director André Téchiné turned that play into a film, The Girl on the Train (or, if you prefer the more evocative French title, The Girl from the RER), which is presently crawling its way across U.S. art theaters, where it is enjoying the fixed attention of dozens, if not scores, of viewers.

It's probably just as well: Téchiné is not the world's easiest filmmaker, and The Girl on the Train is a particularly gnarly knot of a movie: focusing its entire attention on one outrageous, unsupportable lie - the moment that the protagonist, Jeanne (Émilie Dequenne), announces that she's been "attacked", the movie itself breaks into two parts - and making no real effort to explain what the hell is going on in the mind of the liar. Do we walk out of the theater making conjectures about what made Jeanne do this thing, one in a string of unfathomable choices she makes over the course of the plot? Yes, undoubtedly. And my conjectures aren't likely to be the same as your conjectures. The film is in some ways a tabula rasa that permits the viewer to reflect at his or her leisure, but it is not a puzzle with a solution. Just for fun, check out the film's Metacritic page: at this writing, you can find two consecutive pullquotes declaring that it's "really about... people. Just regular people" and "What the film is really about is social embarrassment".

What it's really about is Jeanne, her mother Louise (Catherine Deneuve, whom convention requires me to refer to as "the great Catherine Deneuve"), her unsavory temporary boyfriend Franck (Nicolas Duvauchelle), and the Bleistein family: Samuel (Michel Blanc), a famous lawyer and old friend of Louise's, his son Alex (Mathieu Demy), his daughter-in-law Judith (Ronit Elkabetz), and in some ways most importantly, his grandson Nathan (Jérémy Quaegebeur), preparing for his bar mitzvah. There are both superficial and probing ways that the two main lines of the plot - Jeanne and her mother vs. Nathan and his parents - mirror and/or contrast each other; there is the coolness between Jeanne and Louise that sometimes pierces (a recurrent image of Louise playing with the young children she's watching while Jeanne watches from a distance is, I think, the closest we come to an explanation for what happened), while Nathan's feelings towards Alex are nearly as icy; but the Bleisteins, unlike their gentile counterparts, also have a messy kind of personal intimacy that doesn't curdle, though it still causes problems for them. I should rather let the individual viewer tease out these sorts of connections, though, since in a very real sense watching The Girl on the Train is a matter of witnessing these connections organically rise up from the scenario.

As the plot slides, on, with Louise inducing Samuel to take up Jeanne's case although both of them believe more or less that she's lying, the film's questions become thicker and more confusing, leading the story into corners that never find any sort of traditionally satisfying resolution. The film does not want to part with its meaning readily, and in a certain sense, this is a strike against it: there comes a point where opacity shades into smug pretension, although the details we observe of the characters, and even more the performances giving the characters life (Dequenne is particularly transfixing, all the more since she has by far the most veiled role to play), leave the film with enough of a beating human heart that I can't really fathom how anyone could honestly accuse it of being pretentious. Still, it's an experience that is more valuable for the challenge it poses to the audience than the statements it makes. That's not really a fun night out at the movies, any way you slice it.

A master craftsman, Téchiné does what he can to make the experience a smooth one through the incredibly judicious use of camera angles, and even more so with a peculiar but wildly effective editing trick that pops up over and over again: the film cuts from one shot of a character to another shot, very similarly if not identically framed, in the same location - it looks, at first, like the film has a stutter. It keeps the audience from getting properly situated, and suggests a fragmentary reality in keeping with the script's refusal to give us answers: who can say what's "true" about a situation that won't even hold still and have the decency not to keep jump-cutting? Less cutely: the editing rather unmistakably violates the film's realism, which in turn devalues that realism, which in turn devalues the explanation for the film's reality.

Characteristically, Téchiné also uses some great musical cues, along with an excellent original score by Philippe Sarde; there are several moments in the film, beginning with its masterful opening shot (the POV of a train barreling through a subway tunnel, with the exit just a tiny dot in the far distance, as lights rush past) set to a peculiar, militaristic bagpipe piece, on to the moody use of Bob Dylan's "Lay Lady Lay" to accompany a pantomime montage revealing how disconnected Jeanne feels from the rest of the world - itself a repeated motif, especially in the first half, and it's not probably that two of the film's best scenes consist of Jeanne listening to music through headphones and ignoring the world around her - there's always a deep, intuitive rightness to the music, the kind that makes sense almost despite your attempt to consciously figure out why.

I suppose there are people who will be frustrated with the film's slow pace (it is a very long 105 minutes) and its practiced ambiguity, but The Girl on the Train is a character study par excellence, that simmers and lingers and reveals itself only by inches. The demands it makes upon its audience are not tiny, but its rewards are very considerable: it allows us to ponder how human beings think, without asking that we be judgmental or reductive.