Russian around

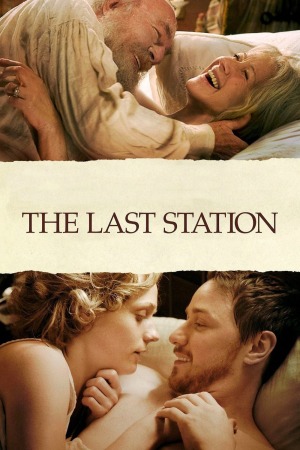

One last toe-dip into the seas of platform-released prestige pictures, and life can move on to more interesting and important things - I am given to understand that a known pedophile has a thriller about the publishing industry that just opened this past weekend - but the last death rattle of Oscar season 2009 is a pretty rough bastard to deal with, not bad so much as it is compulsively and abjectly pokey. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you the The Last Station, which is maybe about the chaotic whirlwind surrounding Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy in the last months of his life, and maybe about a bright-eyed youth who learns a great deal about the world by meeting famous people, and there's a character who's either a shrieking harridan or the one and only sympathetic person in the whole movie. I don't really know, and the film is nowhere nearly good enough to make me care. I guess maybe it's mostly about giving Helen Mirren something chewy to play with while we wait for Julie Taymor's Tempest adaptation to emerge from whatever hole in the smoldering ruins of Miramax it has been hiding in.

1910, Moscow: 23-year-old Valentin Bulgakov (James McAvoy) is an earnest Tolstoyan - the Tolstoyans being a group following the Christian anarcho-pacisfist communitarian philosophies developed by Tolstoy in his old age, and living ascetic lives (veganism, abstinence, and so on) - who has the richest of all opportunities: Tolstoy's close friend and advisor, Vladimir Chertkov (Paul Giamatti), has just hired him to be the great author's personal secretary in the Tolstoy's country home, very near the farming commune that Chertkov established in Tolstoy's name. Valentin is ecstatic, of course, but finds that life in the Tolstoy home is not at all peaceful: the octogenarian count (Christopher Plummer) is in a state of perpetual warfare with his wife, Sofya Andreyevna (Helen Mirren), over the future dispensation of his vast fortune. Tolstoy, with the support of Chertkov, wishes to leave his copyrights and property to the Russian people, while Sofya is terrified at the thought of their children being left penniless. As if this weren't enough to keep Valentin off-balance, one of the communitarians, Masha (Kerry Condon) has caught his eye, and it's proving rather difficult for him to keep up with Tolstoyanism, especially the "abstinence" bit.

The Great Big Problem - actually, the only problem, but it's so overwhelming that the rest of the film has no prayer of recovering from it - is that The Last Station absolutely doesn't know what kind of movie it wants to be. Everything about the first hour or so (it comes in just a touch under two hours) suggests a lively chamber farce, with two erudite people screaming invective at each other (and both Mirren and Plummer manage, if nothing else, to convincingly scream invective), and everything about the final act suggests a costume drama biopic, complete with big, heaving emotion all over. So far, so good: it's a movie that developes its tone over time. Except that it's not really a farce at the beginning, and not really a drama at the end: in the first half, only Mirren seems to have even the slightest interest in making her material play as very funny, and throughout the whole piece, writer-director Michael Hoffman (adapted a 1990 novel by Jay Parini) is infinitely more fascinated by the structure and internal politicking of the Tolstoyan movement than he is by anything do with characterisation, and given that the only throughline connecting the two dissonant halves of the film is the idea that the Tolstoys are still madly in love even though they can't stand each other, a lack of concrete characterisation is absolutely deadly.

There are at least three candidates for lead character, and they're not all compatible with each other: the parallel of Valentin's story to Tolstoy's reluctance to leave his wife behind works, as does the parallel of Valentin's story to Sofya's misery at knowing the man she loved is pulling away from her. Unfortunately, the emphasis on both Tolstoy and Sofya doesn't work at all, largely because it requires the film to strike a balance between two representations of the countess that absolutely cannot fit in the same narrative: is she greedy, selfish, and shrill, or is she motivated only by pure love and the desperate fear of being alone? That the film keeps coming down on the side of the latter is due mostly to how unambiguously Chertkov is presented as a horrible little weasel, with Giamatti engaged in honest-to-God mustache-twirling in some scenes; but still, it never becomes absolutely clear if we're laughing at Sofya or crying with her, and the film isn't deft enough to capture both of those positions at the same time. Mirren's uncharacteristically slight performance doesn't help matters one iota; I can't recall any other time that the actress so clearly just showed up for a paycheck and an Oscar nomination, operating almost completely on autopilot, except for a couple scenes where she opens up and has fun. And I say this as a committed Mirren cultist, mind you - shit, I saw Calendar Girls twice.

Really, the only stand-out performance in the film is not fellow Oscar nominee Plummer (who, with his big white beard, overplays like an irritable Santa Claus by way of Brian Blessed), nor Giamatti (visibly bored), but McAvoy, who has the unenviable task of being the guy in the plot who is totally reactive, but he captures a certain essence of the young idealist that serves him well (though doesn't he always?), and consistently leads to the movie's best moments: which for me are his first meeting with Tolstoy, where the youth uncontrollably starts crying from joy, and his deflowering, a tender moment that is one of the most generous such scenes I can recall, playing up the sweetness of the event rather than the awkwardness. It's a great deal subtler than what Mirren and Plummer are doing, largely because it's so much less Written; so it's not surprising that he's been completely overshadowed.

Hoffman's handling of the material is stiff and inelegant (check out his filmography: "stiff and inelegant" could be on his business cards), and what should bubble is flat; what should flash is dim; what should be powerfully moving is sleepy. The film so palpably wants to be a bittersweet literary confection, but it has the taste of a truffle that was inadvertently made with salt instead of sugar. To be absolutely fair, the film's treatment of the marginal material, like the nature of the commune, Tolstoy's relationship with the outside world and especially Russia in the decade before the Communist revolution, all of that stuff is fascinating and well-presented, and I would be delighted to watch a movie delving into those subjects. It would, of a certainty, be more engaging than the enforced false vitality of this Russian knock-off of The Awful Truth

5/10.

1910, Moscow: 23-year-old Valentin Bulgakov (James McAvoy) is an earnest Tolstoyan - the Tolstoyans being a group following the Christian anarcho-pacisfist communitarian philosophies developed by Tolstoy in his old age, and living ascetic lives (veganism, abstinence, and so on) - who has the richest of all opportunities: Tolstoy's close friend and advisor, Vladimir Chertkov (Paul Giamatti), has just hired him to be the great author's personal secretary in the Tolstoy's country home, very near the farming commune that Chertkov established in Tolstoy's name. Valentin is ecstatic, of course, but finds that life in the Tolstoy home is not at all peaceful: the octogenarian count (Christopher Plummer) is in a state of perpetual warfare with his wife, Sofya Andreyevna (Helen Mirren), over the future dispensation of his vast fortune. Tolstoy, with the support of Chertkov, wishes to leave his copyrights and property to the Russian people, while Sofya is terrified at the thought of their children being left penniless. As if this weren't enough to keep Valentin off-balance, one of the communitarians, Masha (Kerry Condon) has caught his eye, and it's proving rather difficult for him to keep up with Tolstoyanism, especially the "abstinence" bit.

The Great Big Problem - actually, the only problem, but it's so overwhelming that the rest of the film has no prayer of recovering from it - is that The Last Station absolutely doesn't know what kind of movie it wants to be. Everything about the first hour or so (it comes in just a touch under two hours) suggests a lively chamber farce, with two erudite people screaming invective at each other (and both Mirren and Plummer manage, if nothing else, to convincingly scream invective), and everything about the final act suggests a costume drama biopic, complete with big, heaving emotion all over. So far, so good: it's a movie that developes its tone over time. Except that it's not really a farce at the beginning, and not really a drama at the end: in the first half, only Mirren seems to have even the slightest interest in making her material play as very funny, and throughout the whole piece, writer-director Michael Hoffman (adapted a 1990 novel by Jay Parini) is infinitely more fascinated by the structure and internal politicking of the Tolstoyan movement than he is by anything do with characterisation, and given that the only throughline connecting the two dissonant halves of the film is the idea that the Tolstoys are still madly in love even though they can't stand each other, a lack of concrete characterisation is absolutely deadly.

There are at least three candidates for lead character, and they're not all compatible with each other: the parallel of Valentin's story to Tolstoy's reluctance to leave his wife behind works, as does the parallel of Valentin's story to Sofya's misery at knowing the man she loved is pulling away from her. Unfortunately, the emphasis on both Tolstoy and Sofya doesn't work at all, largely because it requires the film to strike a balance between two representations of the countess that absolutely cannot fit in the same narrative: is she greedy, selfish, and shrill, or is she motivated only by pure love and the desperate fear of being alone? That the film keeps coming down on the side of the latter is due mostly to how unambiguously Chertkov is presented as a horrible little weasel, with Giamatti engaged in honest-to-God mustache-twirling in some scenes; but still, it never becomes absolutely clear if we're laughing at Sofya or crying with her, and the film isn't deft enough to capture both of those positions at the same time. Mirren's uncharacteristically slight performance doesn't help matters one iota; I can't recall any other time that the actress so clearly just showed up for a paycheck and an Oscar nomination, operating almost completely on autopilot, except for a couple scenes where she opens up and has fun. And I say this as a committed Mirren cultist, mind you - shit, I saw Calendar Girls twice.

Really, the only stand-out performance in the film is not fellow Oscar nominee Plummer (who, with his big white beard, overplays like an irritable Santa Claus by way of Brian Blessed), nor Giamatti (visibly bored), but McAvoy, who has the unenviable task of being the guy in the plot who is totally reactive, but he captures a certain essence of the young idealist that serves him well (though doesn't he always?), and consistently leads to the movie's best moments: which for me are his first meeting with Tolstoy, where the youth uncontrollably starts crying from joy, and his deflowering, a tender moment that is one of the most generous such scenes I can recall, playing up the sweetness of the event rather than the awkwardness. It's a great deal subtler than what Mirren and Plummer are doing, largely because it's so much less Written; so it's not surprising that he's been completely overshadowed.

Hoffman's handling of the material is stiff and inelegant (check out his filmography: "stiff and inelegant" could be on his business cards), and what should bubble is flat; what should flash is dim; what should be powerfully moving is sleepy. The film so palpably wants to be a bittersweet literary confection, but it has the taste of a truffle that was inadvertently made with salt instead of sugar. To be absolutely fair, the film's treatment of the marginal material, like the nature of the commune, Tolstoy's relationship with the outside world and especially Russia in the decade before the Communist revolution, all of that stuff is fascinating and well-presented, and I would be delighted to watch a movie delving into those subjects. It would, of a certainty, be more engaging than the enforced false vitality of this Russian knock-off of The Awful Truth

5/10.