The films of Miyazaki Hayao: Nothing that happens is ever forgotten, even if you can't remember it

After completing Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki Hayao issued one of those threats that directors sometimes do: having found the experience of making that film so grueling, he'd elected to abandon filmmaking altogether, dedicating his time instead to the planned Ghibli Museum, and to the studio itself, where he would stay on as an executive. It never works out like that, though, and after only a couple years of this semi-retirement, Miyazaki happened to spend some time with the pre-teen daughters of a family he was friends with. It occurred to him during this visit that he'd never made a film for people in that nebulous age between childhood and adolescence; and he grew certain that the images and ideas presented to that age group weren't what really spoke to their hearts and souls. Without any fanfare, he simply slipped out of retirement to create a fantasy about a 10-year-old girl, and how she learns to be mature and responsible.

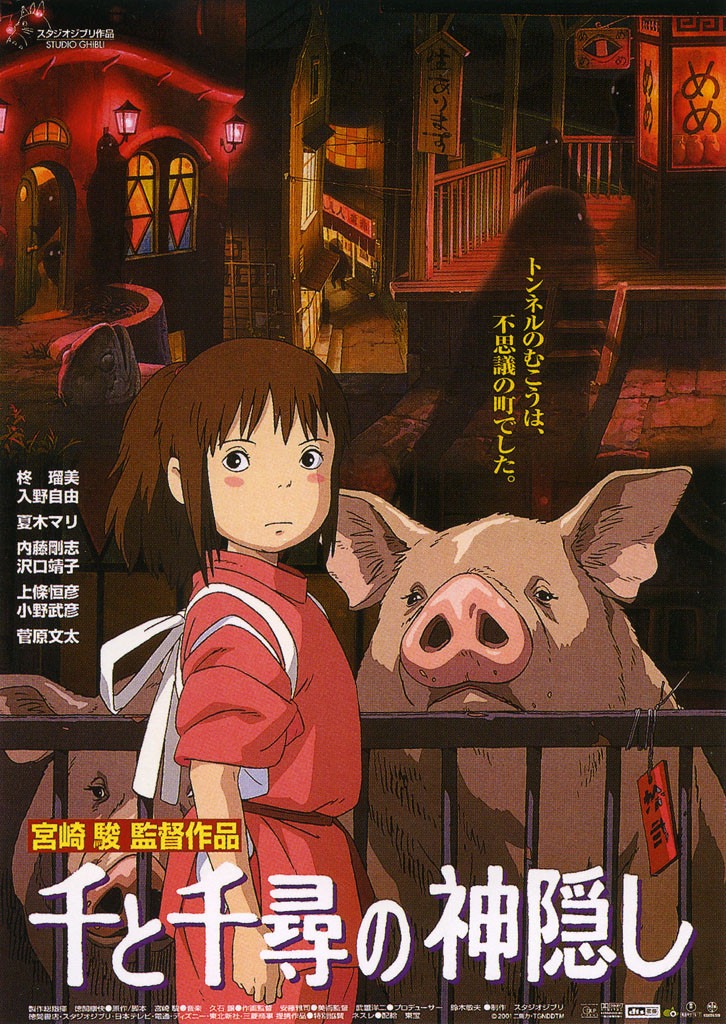

Thank whatever gods are listening for indecisive directors and their inability to commit to retirement, because Spirited Away, Miyazaki's 2001 return to his art, is positively miraculous. I wouldn't feel the need to argue too strenuously with anyone who tried to convince me that it was the masterpiece of his career, though I would not agree, but that's of little matter. What matters is the film itself: a gorgeous fantasy steeped in the iconography and spirituality of Japan, but with a narrative structure that equally calls to mind Western fairy stories; and the most visually sublime of all Miyazaki's films, creating a universe of impossible creatures and magnificent, evocative structures and landscapes in a way that only cinematic animation could ever achieve. It is, at heart, just another plot-light parade of grotesques in the Alice's Adventures in Wonderland model, but given life with fuller characters and grander fantasy than most of that genre's numerous examples would dare to reach for. It was also something of a return to form: after more than a decade of somewhat more mature films, Miyazaki was back in the realm of children's fantasy (that could, by all means, be thoroughly enjoyed by anyone), with a sharp edge of cuteness. If it's more ambiguous, ultimately, than a Kiki's Delivery Service, it's far less sober and difficult than its predecessor or Porco Rosso.

Naturally, it's quite a simple scenario: Chihiro (Hîragi Rumi) is moving with her parents to a new town, and she's not happy about it. Along they way, the family gets lost, and they decide to explore the ruins of an amusement park built in the heyday of Japan's bubble economy in the early 1990s. As her parents gorge themselves on food that inexplicably appears in the ruins, Chihiro suffers from a foreboding that proves terribly true: at nightfall, the park is light with ghostly lights, Chihiro's parents transform into pigs, and a march of otherworldly creatures presents itself. The girl soon learns that she's stuck in the spirit world, at the site of a bathhouse for the gods, run by the dictatorial Yubaba (Natsuki Mari). In this place where humans are given no more attention beyond their value as food, Chihiro is able to find work, thanks to the kindly intervention of Yubaba's lieutenant, Haku (Irino Miyu), a worker named Lin (Tamai Yumi), and Kamaji (Sugawara Bunta), who operates the boilers that keep the bathhouse running. To survive and save her parents, Chihiro must learn to rely on skills she'd never recognised in herself, and in so do doing pass beyond the sullen little girl she is when we first meet her.

Hooray for me, I can reduce a story to its simplest elements. Believe me, it does no good to the movie that I've done so. Spirited Away is full of riches, thematic and visual, and the best way to understand them is simply to watch the film and take it all in. It's not a crafty, confusing film that you need a roadmap to navigate; Miyazaki's genius generally is that his films are so obvious without being obnoxious about it, and this is perhaps the greatest of them all in that respect. Frightfully dense in places, the viewer is nonetheless intuitively aware of exactly what each beat of the story means, and responds in accordance emotionally. The film has the uncanny feeling of moving right through you, operating on something more internal and personal than just your mind.

In essence, the filmmaker is playing the audience like so many fiddles, but when the result is as stunning to the eye and the heart as Spirited Away, it's really not worth complaining. We go to the movies to be moved, after all, and Miyazaki's film does that in spades.

The biggest reason why is Chihiro herself; despite some stiff competition for the title, I'd be inclined to proclaim her the most sympathetic, and appealing protagonist anywhere in Miyazaki's filmography. A lot of this has to do simply with her design: she falls in an extremely narrow range of looking enough like a cartoon that it doesn't feel (as it often does with Miyazaki's young women) that she's meant to be "realistic"; at the same time, she's not so impossible that we can't relate to her. There are a few examples in Miyazaki's films of characters who thread the same needle of caricature and realism (Mei in My Neighbor Totoro leaps to mind first), but even then, few characters are called upon to exhibit such a full range of expressions as Chihiro, and her design allows for that, as well.

There's also the far-from-insignificant matter of how Chihiro is presented to the audience. The very first shot of the movie is from her perspective, staring at her feet. And the opening scene is basically comprised of nothing but either similar POV shots, or medium shots of the girl herself; in no uncertain terms, we are being conditioned from the very first seconds of the film to identify with Chihiro, and to watch for her.

There's also the far-from-insignificant matter of how Chihiro is presented to the audience. The very first shot of the movie is from her perspective, staring at her feet. And the opening scene is basically comprised of nothing but either similar POV shots, or medium shots of the girl herself; in no uncertain terms, we are being conditioned from the very first seconds of the film to identify with Chihiro, and to watch for her.

As for her personality, despite the unpleasant details that she needs to grow out of (the coming-of-age element of Spirited Away), she's actually quite a smart kid. She intuitively understands, as her parents do not, to stay away from the tunnel leading to the spirit-infested amusement park, she has the good sense to not eat the enchanted food, and throughout her adventure she is always well in possession of her wits, without which she would die a number of times over. Like all wise children, in other words, she understands the rules of a fairy tale universe without having to have them explained, and it's not an accident that Spirited Away is the best cinematic fairy tale of its kind (the innocent journeying to the Other World) to come out in years, and maybe decades. Chihiro is an ideal protagonist for such a story, because she doesn't ask needless questions, but allows the reality of what's happening to her to unfold naturally. This is not a beloved mode of modern storytellers, who like to have everything explained clearly; perhaps it's simply the result of the different focus of Japanese fantasy compared to American fantasy, and perhaps it's just that Miyazaki is more interested in effects than causes.

Here, the effects are positively stunning. It's the first thing that anyone notices about Spirited Away, that it's a right cavalcade of fantastic images like nothing else, and I would rather not harp on that, because the only two options I see are to spend thousands of words and tens of screenshots on gushing over the film's marvels, or simply to mention that they exist, and hope that the reader knows what I'm talking about, or is sufficiently curious to seek the film out.

There may be no nobler aim in animation than to provide wonders that could not otherwise be seen; if that is the case, Spirited Away is perhaps the most noble animated film of all time, for it is almost nothing but wonders, though they are never arbitrary and always anchored to the film's emotional honesty. We are never dazzled for the sake of it; we are dazzled because Chihiro is dazzled. We are never delighted, terrified, amazed, or comforted, except as those things happen to our protagonist. And thankfully, her writer and director knew enough of children to make her a guileless innocent without making her stupid, and to allow her the space to feel awe without forcing her into empty spectacle. I think, for example, of the amazing sequence when the spirit world first manifests itself around Chihiro: the environment changes slowly and at times subliminally, while maybe the finest piece of music in Joe Hisaishi's long collaboration with Miyazaki imparts a feeling of simultaneous dread and exotic mystery to the eerie images. It's a perfect sequence, visionary while also making good story sense and further tying our perceptions to Chihiro's emotions. That's the great achievement of this great animated film: it understands that the true meaning of fantastic worlds is not what they show us, but how they make us feel in doing so.

There may be no nobler aim in animation than to provide wonders that could not otherwise be seen; if that is the case, Spirited Away is perhaps the most noble animated film of all time, for it is almost nothing but wonders, though they are never arbitrary and always anchored to the film's emotional honesty. We are never dazzled for the sake of it; we are dazzled because Chihiro is dazzled. We are never delighted, terrified, amazed, or comforted, except as those things happen to our protagonist. And thankfully, her writer and director knew enough of children to make her a guileless innocent without making her stupid, and to allow her the space to feel awe without forcing her into empty spectacle. I think, for example, of the amazing sequence when the spirit world first manifests itself around Chihiro: the environment changes slowly and at times subliminally, while maybe the finest piece of music in Joe Hisaishi's long collaboration with Miyazaki imparts a feeling of simultaneous dread and exotic mystery to the eerie images. It's a perfect sequence, visionary while also making good story sense and further tying our perceptions to Chihiro's emotions. That's the great achievement of this great animated film: it understands that the true meaning of fantastic worlds is not what they show us, but how they make us feel in doing so.

Thank whatever gods are listening for indecisive directors and their inability to commit to retirement, because Spirited Away, Miyazaki's 2001 return to his art, is positively miraculous. I wouldn't feel the need to argue too strenuously with anyone who tried to convince me that it was the masterpiece of his career, though I would not agree, but that's of little matter. What matters is the film itself: a gorgeous fantasy steeped in the iconography and spirituality of Japan, but with a narrative structure that equally calls to mind Western fairy stories; and the most visually sublime of all Miyazaki's films, creating a universe of impossible creatures and magnificent, evocative structures and landscapes in a way that only cinematic animation could ever achieve. It is, at heart, just another plot-light parade of grotesques in the Alice's Adventures in Wonderland model, but given life with fuller characters and grander fantasy than most of that genre's numerous examples would dare to reach for. It was also something of a return to form: after more than a decade of somewhat more mature films, Miyazaki was back in the realm of children's fantasy (that could, by all means, be thoroughly enjoyed by anyone), with a sharp edge of cuteness. If it's more ambiguous, ultimately, than a Kiki's Delivery Service, it's far less sober and difficult than its predecessor or Porco Rosso.

Naturally, it's quite a simple scenario: Chihiro (Hîragi Rumi) is moving with her parents to a new town, and she's not happy about it. Along they way, the family gets lost, and they decide to explore the ruins of an amusement park built in the heyday of Japan's bubble economy in the early 1990s. As her parents gorge themselves on food that inexplicably appears in the ruins, Chihiro suffers from a foreboding that proves terribly true: at nightfall, the park is light with ghostly lights, Chihiro's parents transform into pigs, and a march of otherworldly creatures presents itself. The girl soon learns that she's stuck in the spirit world, at the site of a bathhouse for the gods, run by the dictatorial Yubaba (Natsuki Mari). In this place where humans are given no more attention beyond their value as food, Chihiro is able to find work, thanks to the kindly intervention of Yubaba's lieutenant, Haku (Irino Miyu), a worker named Lin (Tamai Yumi), and Kamaji (Sugawara Bunta), who operates the boilers that keep the bathhouse running. To survive and save her parents, Chihiro must learn to rely on skills she'd never recognised in herself, and in so do doing pass beyond the sullen little girl she is when we first meet her.

Hooray for me, I can reduce a story to its simplest elements. Believe me, it does no good to the movie that I've done so. Spirited Away is full of riches, thematic and visual, and the best way to understand them is simply to watch the film and take it all in. It's not a crafty, confusing film that you need a roadmap to navigate; Miyazaki's genius generally is that his films are so obvious without being obnoxious about it, and this is perhaps the greatest of them all in that respect. Frightfully dense in places, the viewer is nonetheless intuitively aware of exactly what each beat of the story means, and responds in accordance emotionally. The film has the uncanny feeling of moving right through you, operating on something more internal and personal than just your mind.

In essence, the filmmaker is playing the audience like so many fiddles, but when the result is as stunning to the eye and the heart as Spirited Away, it's really not worth complaining. We go to the movies to be moved, after all, and Miyazaki's film does that in spades.

The biggest reason why is Chihiro herself; despite some stiff competition for the title, I'd be inclined to proclaim her the most sympathetic, and appealing protagonist anywhere in Miyazaki's filmography. A lot of this has to do simply with her design: she falls in an extremely narrow range of looking enough like a cartoon that it doesn't feel (as it often does with Miyazaki's young women) that she's meant to be "realistic"; at the same time, she's not so impossible that we can't relate to her. There are a few examples in Miyazaki's films of characters who thread the same needle of caricature and realism (Mei in My Neighbor Totoro leaps to mind first), but even then, few characters are called upon to exhibit such a full range of expressions as Chihiro, and her design allows for that, as well.

There's also the far-from-insignificant matter of how Chihiro is presented to the audience. The very first shot of the movie is from her perspective, staring at her feet. And the opening scene is basically comprised of nothing but either similar POV shots, or medium shots of the girl herself; in no uncertain terms, we are being conditioned from the very first seconds of the film to identify with Chihiro, and to watch for her.

There's also the far-from-insignificant matter of how Chihiro is presented to the audience. The very first shot of the movie is from her perspective, staring at her feet. And the opening scene is basically comprised of nothing but either similar POV shots, or medium shots of the girl herself; in no uncertain terms, we are being conditioned from the very first seconds of the film to identify with Chihiro, and to watch for her.As for her personality, despite the unpleasant details that she needs to grow out of (the coming-of-age element of Spirited Away), she's actually quite a smart kid. She intuitively understands, as her parents do not, to stay away from the tunnel leading to the spirit-infested amusement park, she has the good sense to not eat the enchanted food, and throughout her adventure she is always well in possession of her wits, without which she would die a number of times over. Like all wise children, in other words, she understands the rules of a fairy tale universe without having to have them explained, and it's not an accident that Spirited Away is the best cinematic fairy tale of its kind (the innocent journeying to the Other World) to come out in years, and maybe decades. Chihiro is an ideal protagonist for such a story, because she doesn't ask needless questions, but allows the reality of what's happening to her to unfold naturally. This is not a beloved mode of modern storytellers, who like to have everything explained clearly; perhaps it's simply the result of the different focus of Japanese fantasy compared to American fantasy, and perhaps it's just that Miyazaki is more interested in effects than causes.

Here, the effects are positively stunning. It's the first thing that anyone notices about Spirited Away, that it's a right cavalcade of fantastic images like nothing else, and I would rather not harp on that, because the only two options I see are to spend thousands of words and tens of screenshots on gushing over the film's marvels, or simply to mention that they exist, and hope that the reader knows what I'm talking about, or is sufficiently curious to seek the film out.

There may be no nobler aim in animation than to provide wonders that could not otherwise be seen; if that is the case, Spirited Away is perhaps the most noble animated film of all time, for it is almost nothing but wonders, though they are never arbitrary and always anchored to the film's emotional honesty. We are never dazzled for the sake of it; we are dazzled because Chihiro is dazzled. We are never delighted, terrified, amazed, or comforted, except as those things happen to our protagonist. And thankfully, her writer and director knew enough of children to make her a guileless innocent without making her stupid, and to allow her the space to feel awe without forcing her into empty spectacle. I think, for example, of the amazing sequence when the spirit world first manifests itself around Chihiro: the environment changes slowly and at times subliminally, while maybe the finest piece of music in Joe Hisaishi's long collaboration with Miyazaki imparts a feeling of simultaneous dread and exotic mystery to the eerie images. It's a perfect sequence, visionary while also making good story sense and further tying our perceptions to Chihiro's emotions. That's the great achievement of this great animated film: it understands that the true meaning of fantastic worlds is not what they show us, but how they make us feel in doing so.

There may be no nobler aim in animation than to provide wonders that could not otherwise be seen; if that is the case, Spirited Away is perhaps the most noble animated film of all time, for it is almost nothing but wonders, though they are never arbitrary and always anchored to the film's emotional honesty. We are never dazzled for the sake of it; we are dazzled because Chihiro is dazzled. We are never delighted, terrified, amazed, or comforted, except as those things happen to our protagonist. And thankfully, her writer and director knew enough of children to make her a guileless innocent without making her stupid, and to allow her the space to feel awe without forcing her into empty spectacle. I think, for example, of the amazing sequence when the spirit world first manifests itself around Chihiro: the environment changes slowly and at times subliminally, while maybe the finest piece of music in Joe Hisaishi's long collaboration with Miyazaki imparts a feeling of simultaneous dread and exotic mystery to the eerie images. It's a perfect sequence, visionary while also making good story sense and further tying our perceptions to Chihiro's emotions. That's the great achievement of this great animated film: it understands that the true meaning of fantastic worlds is not what they show us, but how they make us feel in doing so.