They call it puppy love

If Amores perros had not premiered in the summer of 2000, it would be necessary to lie and say that it had done so; offhand I cannot name another movie which has ever thus stood at the forefront of what would turn out to be a number of different trends in the decade to follow, while providing such a clear picture of the evolution from the trends of the decade that preceded, as Alejandro González Iñárritu's unnaturally accomplished debut feature. Viewed from the perspective of the year 2000, I recall seeing it as an unusually edgy, creative take-off on Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction: there was a similar three-part narrative, shuffled somewhat out of chronological order, involving different sets of characters who overlapped at certain points, and it was set in a world of low-rent gangsters and daydreaming tough guys. Tarantino knock-offs, you may recall, were just about the most prominent subgenre of movies, from countries all 'round the world, in the latter half of the 1990s, just as certainly as Matrix knock-offs, in one guise or another, were the backbone of the first half of the 2000s, so in this respect Amores perros hardly seemed a film to usher in a new kind of cinema, although it was clear to all that it was a damn sight better than nearly all of the other post-Tarantino films out there.

Ten years later, it's hard not to look at that same film and notice above all to the key things it did differently from that glut of hip crime films; for it is those things that proved to be so influential in the years to come. In Guillermo Arriaga's script for Amores perros, we see one of the first pure example of what would come to be called the "hyperlink film", a narrative style in which disconnected stories are revealed to have overlap and connection that only becomes obvious as we hope about from event to event and character to character in what at first seems a random series of non-events, but slowly reveals itself to have distinct meaning and a precise rhythm all its own. Only Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia from 1999 can be rightfully said to predate Amores perros in the creation of this unique narrative form, though it was another 2000 film, Traffic, that really got things rolling as far as making that form so popular as it became throughout the decade, when it began to truly wear out its welcome and go from being a fresh, compelling way to structure narrative threads, to being a wholly irritating cliché in such films as Gonzálex Iñárritu and Arriaga's last collabartion, 2006's shallow, suffocating Babel.

Amores perros is also, if not the first significant example, then the first of which I am aware, of a trend in cinematography that has become somewhat clichéd itself, though not nearly as irritating: the high-grain, high-contrast, "looks cheap but also has a kind of raw beauty" look that is the very bread and butter of Rodrigo Prieto, one of the decade's great practitioners of that art form who made his international splash with this very film, before moving on to create similar visuals for Curtis Hanson in 8 Mile and Spike Lee in 25th Hour. Of course, Prieto is not the only practitioner of this style, just the best; at any rate, in the last ten years it has become incredibly difficult to avoid movies on the prestige circuit that subscribe to this same washed-out, grainy look (and I think here, too, Traffic may have been the film to actually kick off the imitators; but Traffic, I fear that Amores Perros beat you to the punch by all of seven months).

While it's not an aesthetic concern at all, it's also worth pointing out that Amores perros was right in the forefront of the Latin American New Wave, or the New Latin American Cinema, or whatever we want to call it. Either way, I'm sure you know what I'm talking about: the sudden explosion of Latin American films in the arthouses, and Latin American craftspeople all throughout world cinema. Some of the most famous of these are Mexican: González Iñárritu himself, along with his good buddies Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuarón; Prieto and Emmanel Lubezki, two of the most talented cinematographers now working; actor Gael García Bernal, who appeared in Amores perros himself. Now, I'm not trying to give credit to this one film for launching all of the Latin American New Wave; but it's something to think about. It was a big damn deal all over the world, something that hadn't been true of a Mexican movie since Luis Buñuel returned to France in the 1960s.

All this historical weight I'm piling on this one movie! And in the midst of it all, I haven't said one word about the most important part of all: when you get right down to it, Amores perros is a pretty great movie all around. Dozens of shoddy imitators have done nothing to disguise the wit of its narrative construction, which in this case isn't simply a matter of making something convoluted for the sheer sake of it (I contend that Arriaga did exactly this in the decent but weirdly overpraised 21 Grams), but serves a tremendously specific function in aiding the film's overall construction of a world gone mad. Amores perros is in all ways a singularly urgent film, telling three stories that each reveal a different facet of how urban life in Mexico is broken across class lines, and the fluidity of its chronology serves to keep the audience just disoriented enough that we can only get a handle on this society in fits and starts.

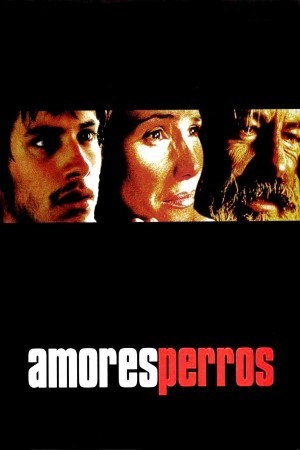

I think the film is not usually given its due as a class-based study: the three stories are, in order, about a poor young man (García Bernal) finding his way into some money and using it unwisely, a model (Goya Toledo) losing her single, mostly superficial talent as a result of accident and foolish judgment, and a homeless man (Emilio Echevarría) hired to assassinate a yuppie. It's hardly the case that Arriaga and González Iñárritu are launching any kind of Marxist polemic about class in Mexico - the film refuses to adopt that kind of certainty about its subjects - but simply noticing that these class issues exist, and that across classes, people tend to make the same sort of mistakes in regards to money and other people; that it is own kind of class statement, no? But thanks to the film's title (Love Dogs, essentially), this element of the movie is obscured by its other two overarching themes: the relationship of humans and non-human animals, dogs specifically, and the different ways that we can love, and more often, fail to love. Which are themes treated with some care, by all means; but I still persist in finding the core of the movie to be its treatment of Mexican society, thanks largely to the overwhelming madness of its narrative and its aesthetic, and the ways that reflects the madness of the society depicted.

Clearly, Prieto's unconventionally-beautiful, i.e. "ugly" cinematography, does much to further this notion; if not only because of the harsh contrast (brought about by his experiments with film stock, experiments not at all well-served by any of the film's DVD iterations), then also because of the jerky movement on display throughout. The editing team (which includes the director) helped in no small way: the cutting in this movie, especially in the first sequence, and especially especially in the very compellingly-faked dog fight scenes, is typically frantic and jarring, though in a much subtler way than has become common in the wake of the Jason Bourne movies. It's that urgency thing, like I was saying: everything about the film is very carefully pitched to keep us as edgy and confused and worked-up as possible, which makes the film's exploration of three very different but ultimately sympathetic social conditions seem that much more alive and important. Even the film's frequent eruptions of man-on-man and dog-on-dog violence add to this urgency, rather than seeming crudely exploitative (though, despite a very stentorian assurance that all the animal violence is faked, it's better that dog lovers with tender stomachs keep far away from this movie).

And that, too, is something that has become a bit more common in the '00s: using the language of violent cinema refined in the '90s (by which I mean both its depiction of violence, and the violence it does to traditional cinematic vocabulary) to give the film a vibrancy and vitality, making the movie itself almost a living, breathing thing, so that we are that much more attentive to the matter within the film. If I can't ultimately call Amores perros one of the full-stop, A+ masterpieces of the decade, it's only because the story does take to wandering a bit too much in the second and third segments, and not because the overall feeling of the movie is anything less than revelatory.

Ten years later, it's hard not to look at that same film and notice above all to the key things it did differently from that glut of hip crime films; for it is those things that proved to be so influential in the years to come. In Guillermo Arriaga's script for Amores perros, we see one of the first pure example of what would come to be called the "hyperlink film", a narrative style in which disconnected stories are revealed to have overlap and connection that only becomes obvious as we hope about from event to event and character to character in what at first seems a random series of non-events, but slowly reveals itself to have distinct meaning and a precise rhythm all its own. Only Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia from 1999 can be rightfully said to predate Amores perros in the creation of this unique narrative form, though it was another 2000 film, Traffic, that really got things rolling as far as making that form so popular as it became throughout the decade, when it began to truly wear out its welcome and go from being a fresh, compelling way to structure narrative threads, to being a wholly irritating cliché in such films as Gonzálex Iñárritu and Arriaga's last collabartion, 2006's shallow, suffocating Babel.

Amores perros is also, if not the first significant example, then the first of which I am aware, of a trend in cinematography that has become somewhat clichéd itself, though not nearly as irritating: the high-grain, high-contrast, "looks cheap but also has a kind of raw beauty" look that is the very bread and butter of Rodrigo Prieto, one of the decade's great practitioners of that art form who made his international splash with this very film, before moving on to create similar visuals for Curtis Hanson in 8 Mile and Spike Lee in 25th Hour. Of course, Prieto is not the only practitioner of this style, just the best; at any rate, in the last ten years it has become incredibly difficult to avoid movies on the prestige circuit that subscribe to this same washed-out, grainy look (and I think here, too, Traffic may have been the film to actually kick off the imitators; but Traffic, I fear that Amores Perros beat you to the punch by all of seven months).

While it's not an aesthetic concern at all, it's also worth pointing out that Amores perros was right in the forefront of the Latin American New Wave, or the New Latin American Cinema, or whatever we want to call it. Either way, I'm sure you know what I'm talking about: the sudden explosion of Latin American films in the arthouses, and Latin American craftspeople all throughout world cinema. Some of the most famous of these are Mexican: González Iñárritu himself, along with his good buddies Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuarón; Prieto and Emmanel Lubezki, two of the most talented cinematographers now working; actor Gael García Bernal, who appeared in Amores perros himself. Now, I'm not trying to give credit to this one film for launching all of the Latin American New Wave; but it's something to think about. It was a big damn deal all over the world, something that hadn't been true of a Mexican movie since Luis Buñuel returned to France in the 1960s.

All this historical weight I'm piling on this one movie! And in the midst of it all, I haven't said one word about the most important part of all: when you get right down to it, Amores perros is a pretty great movie all around. Dozens of shoddy imitators have done nothing to disguise the wit of its narrative construction, which in this case isn't simply a matter of making something convoluted for the sheer sake of it (I contend that Arriaga did exactly this in the decent but weirdly overpraised 21 Grams), but serves a tremendously specific function in aiding the film's overall construction of a world gone mad. Amores perros is in all ways a singularly urgent film, telling three stories that each reveal a different facet of how urban life in Mexico is broken across class lines, and the fluidity of its chronology serves to keep the audience just disoriented enough that we can only get a handle on this society in fits and starts.

I think the film is not usually given its due as a class-based study: the three stories are, in order, about a poor young man (García Bernal) finding his way into some money and using it unwisely, a model (Goya Toledo) losing her single, mostly superficial talent as a result of accident and foolish judgment, and a homeless man (Emilio Echevarría) hired to assassinate a yuppie. It's hardly the case that Arriaga and González Iñárritu are launching any kind of Marxist polemic about class in Mexico - the film refuses to adopt that kind of certainty about its subjects - but simply noticing that these class issues exist, and that across classes, people tend to make the same sort of mistakes in regards to money and other people; that it is own kind of class statement, no? But thanks to the film's title (Love Dogs, essentially), this element of the movie is obscured by its other two overarching themes: the relationship of humans and non-human animals, dogs specifically, and the different ways that we can love, and more often, fail to love. Which are themes treated with some care, by all means; but I still persist in finding the core of the movie to be its treatment of Mexican society, thanks largely to the overwhelming madness of its narrative and its aesthetic, and the ways that reflects the madness of the society depicted.

Clearly, Prieto's unconventionally-beautiful, i.e. "ugly" cinematography, does much to further this notion; if not only because of the harsh contrast (brought about by his experiments with film stock, experiments not at all well-served by any of the film's DVD iterations), then also because of the jerky movement on display throughout. The editing team (which includes the director) helped in no small way: the cutting in this movie, especially in the first sequence, and especially especially in the very compellingly-faked dog fight scenes, is typically frantic and jarring, though in a much subtler way than has become common in the wake of the Jason Bourne movies. It's that urgency thing, like I was saying: everything about the film is very carefully pitched to keep us as edgy and confused and worked-up as possible, which makes the film's exploration of three very different but ultimately sympathetic social conditions seem that much more alive and important. Even the film's frequent eruptions of man-on-man and dog-on-dog violence add to this urgency, rather than seeming crudely exploitative (though, despite a very stentorian assurance that all the animal violence is faked, it's better that dog lovers with tender stomachs keep far away from this movie).

And that, too, is something that has become a bit more common in the '00s: using the language of violent cinema refined in the '90s (by which I mean both its depiction of violence, and the violence it does to traditional cinematic vocabulary) to give the film a vibrancy and vitality, making the movie itself almost a living, breathing thing, so that we are that much more attentive to the matter within the film. If I can't ultimately call Amores perros one of the full-stop, A+ masterpieces of the decade, it's only because the story does take to wandering a bit too much in the second and third segments, and not because the overall feeling of the movie is anything less than revelatory.